Judy Garland’s Long-Lost ‘Wizard of Oz’ Dress Rediscovered After Decades

A lecturer at Catholic University discovered the rare costume wrapped in a trash bag in a drama department office

:focal(1221x2066:1222x2067)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/78/ff/78ff4707-1486-4a6c-aef3-aff5a6f08645/gettyimages-121652862.jpg)

For decades, members of the Catholic University of America (CUA) drama department traded rumors about the location of a long-lost piece of movie magic: a blue-and-white checked gingham dress worn by Judy Garland as Dorothy Gale in the iconic 1939 film The Wizard of Oz. Donated to the Washington, D.C.-based university in the 1970s, the dress hadn’t been seen in years—and even department lecturer and operations coordinator Matt Ripa, who had searched high and low for the costume, had come up empty-handed.

Sometimes, though, dreams really do come true. On June 7, Ripa was cleaning out a building ahead of renovations when he found a mysterious trash bag tucked on top of the faculty mail slots.

“I was curious what was inside and opened the trash bag and inside was a shoebox and inside the shoebox was the dress!!” he recalls in a University Archives blog post. “I couldn’t believe it.”

Speaking with the Washington Post’s Paul Duggan, Ripa adds, “I was shocked, holding a piece of Hollywood history right in my hands.”

The box contained a brief message from Thomas Donahue, a now-retired drama professor who had apparently discovered the dress in the department chair’s office: “I found this.” Thrilled, Ripa and a co-worker donned gloves to snap a few photos of the faded garment before heading over to the archives.

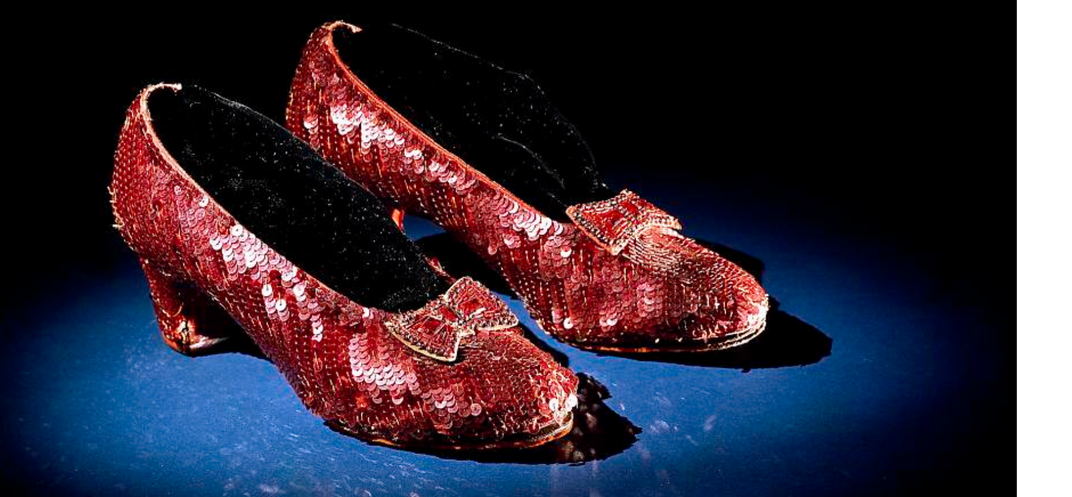

Scholars with the university’s special collections then contacted Ryan Lintelman, a curator at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History (NMAH) and an expert in Wizard of Oz memorabilia. The museum houses a pair of sparkling ruby slippers worn by Garland in its collections, as well as a complete costume worn by Ray Bolger as the brainless Scarecrow and an original 1938 screenplay based on L. Frank Baum’s 1900 book.

Per Institution policy, Smithsonian curators do not offer monetary evaluations of historical objects. But as Lintelman tells Smithsonian magazine, he and conservators Dawn Wallace and Sunae Park Evans determined that the CUA dress numbers among just six known costumes “that have a good claim” on being the real deal.

Lintelman notes that the iconic blue-and-white “dress” was actually composed of two pieces: “a thin cotton blouse with bunched sleeves and blue ric-rac tape trim at its collar” and a “blue and white checked gingham pinafore dress worn over top.”

This simple outfit eventually became one of the most famous ensembles in cinematic history. When a tornado transports Dorothy from sepia-toned Kansas to the magical land of Oz, the heroine’s blue pinafore pops against the film’s Technicolor hues: a yellow brick road, the Emerald City and her beloved ruby slippers, to name a few. According to Hilary Whiteman of CNN Style, the “sensory overload” of Oz’s bright colors was meant to convey its otherworldliness—in other words, the sense that Dorothy wasn’t in Kansas anymore.

For Garland, life as Dorothy was hard work. After long days of sweating and dancing on set, the teenaged actress often ripped the thin dress material where the pinafore straps met the shoulders. Like other costumes she wore on set, the CUA dress is highly worn at the shoulders and bears evidence of small mends from seamstresses. (MGM employed teams of costumers on set and often pushed actors to shoot films on a fast-paced, “factory-like” production schedule, Lintelman notes.)

The newly resurfaced dress features a characteristic “secret pocket” where Garland stored her handkerchief; the actress’ name is also written on the garment in the same handwriting that appears on other known costumes.

Wrapped up in the garment, too, is a sad history of abuse. Later in life, Garland would allege that male studio executives, fellow actors and Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (MGM) Studios founder Louis B. Mayer sexually harassed her while she was on set. MGM managers also forced young Garland to take addictive drugs and starve herself to lose weight—actions that contributed to the addictions and disordered eating habits that plagued the actress for the rest of her life, as Suyin Haynes wrote for Time magazine in 2019.

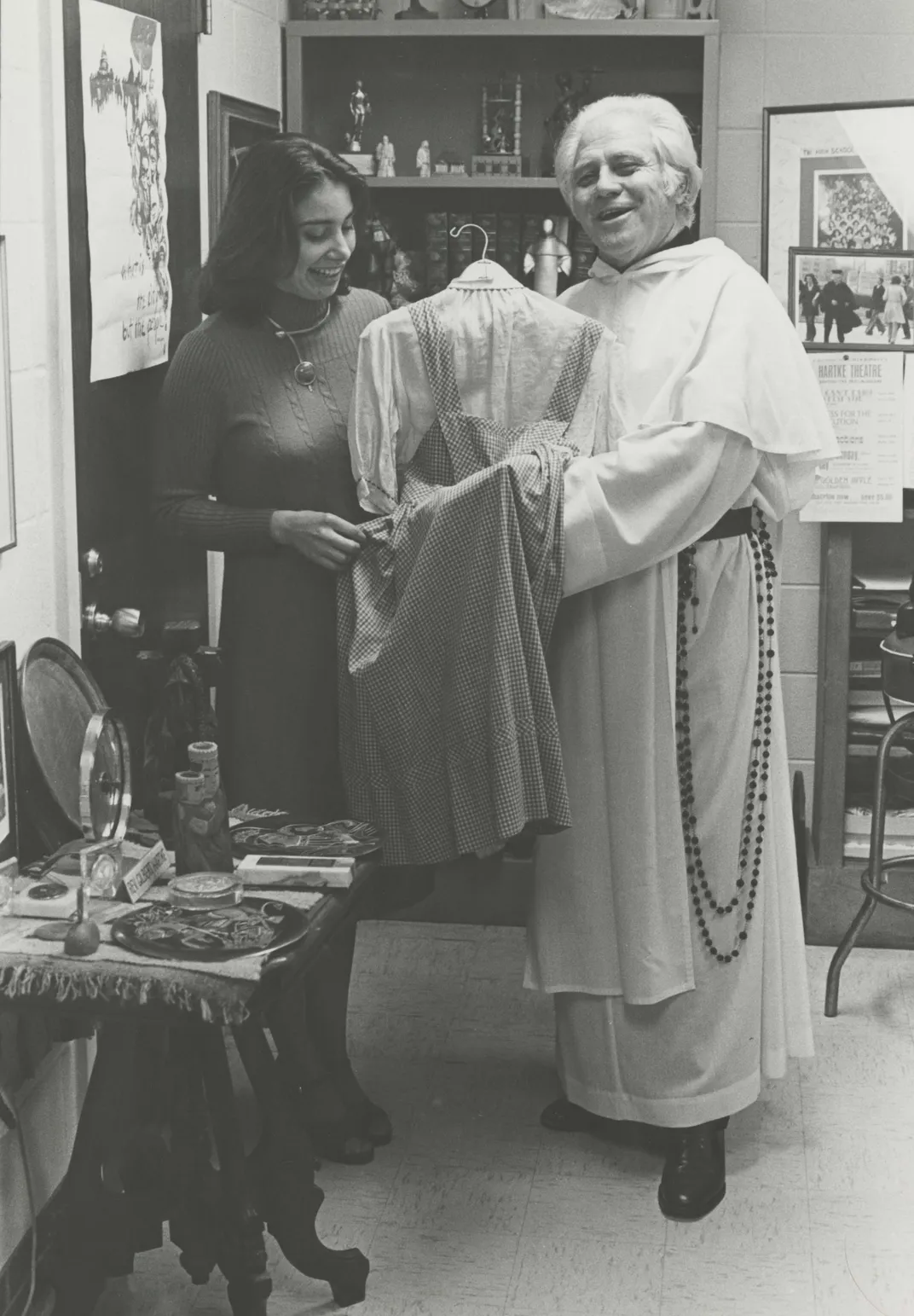

Oscar-winning actress Mercedes McCambridge donated the dress to her close friend, CUA drama department director Father Gilbert Hartke, when she was an artist-in-residence at the school in the early 1970s. An article from student newspaper the Tower describes a 1973 speech in which McCambridge referred to Garland’s addictions and noted that she hoped the dress could be a source of “hope, strength and courage” for students.

Subsequent news articles and photos of Father Hartke holding the dress seem to back up this timeline, says Maria Mazzenga, curator of the American Catholic History Collections at CUA, in a statement.

“[T]he circumstantial evidence [pointing to the costume’s authenticity] is strong,” she adds.

Four years before McCambridge donated the dress, Garland died of an accidental drug overdose at age 47. The university has not determined how McCambridge and Garland knew each other, but the statement notes that they were contemporaries who “were believed to be friends.”

Five other dresses worn by Garland during filming now reside in private hands, says Lintelman. Eventually, CUA curators hope to officially authenticate the rediscovered garment and display it publicly on campus, reports Jacqueline Jedrych for the Tower.

Smithsonian conservators, including Wallace, recently spent two years painstakingly cleaning the pair of sequined ruby slippers in NMAH’s collections. (Though Baum originally described Dorothy’s shoes as silver, movie producers decided to make her footwear red so they would stand out, per the museum.)

“It would be wonderful to discuss reuniting the museum’s ruby slippers with the dress someday for fans of the film to enjoy,” Lintelman says.

The iconic shoes—and the person who wore them—have since had a profound impact on American life.

“Dorothy’s ruby slippers have held great meaning for people ever since 1939,” adds Lintelman, “whether inspiring young women to pursue their dreams, galvanizing community for gay men who identified as ‘friends of Dorothy’ in the 1970s, sparking opportunities for more representative cinema with films like The Wiz, or even just seeding happy memories for so many Americans.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/nora.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/ac/56/ac56845e-553b-478c-a635-488055589303/smithsoniandress.jpeg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/nora.png)