World’s Largest Online Database of Jewish Art Preserves At-Risk Heritage Objects

Take a tour through the Bezalel Narkiss Index of Jewish Art, which contains more than 260,000 entries from 41 countries

The vast landscape of Siberia is dotted with long-abandoned synagogues, the crumbling relics of Jewish communities that once lived there. In 2015, Vladimir Levin, acting director of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem’s Center for Jewish Art, embarked on a mission to document these historic buildings. Accompanied by a team of researchers, Levin traveled by car, train and plane across the hundreds of miles that lay between the synagogues. Many were on the verge of disappearing; they had gone unused for decades, or had been repurposed by local communities, or had been partially dismantled for their construction materials.

Levin knew that he couldn’t save every synagogue he encountered, but he and his team set about photographing and describing the buildings to create a permanent record of their existence. Afterward, they uploaded the information to the Bezalel Narkiss Index of Jewish Art, a new online database that catalogues a vast array of Jewish art and architecture from across the globe.

“Jewish people are moving from one place to another, it's part of our history,” Levin tells Smithsonian.com when describing the purpose of the index, which launched in August. “After us remains a lot of built heritage and other heritage which we will never use again … We believe that it is impossible to [physically] preserve everything, but it is possible to preserve it through documentation.”

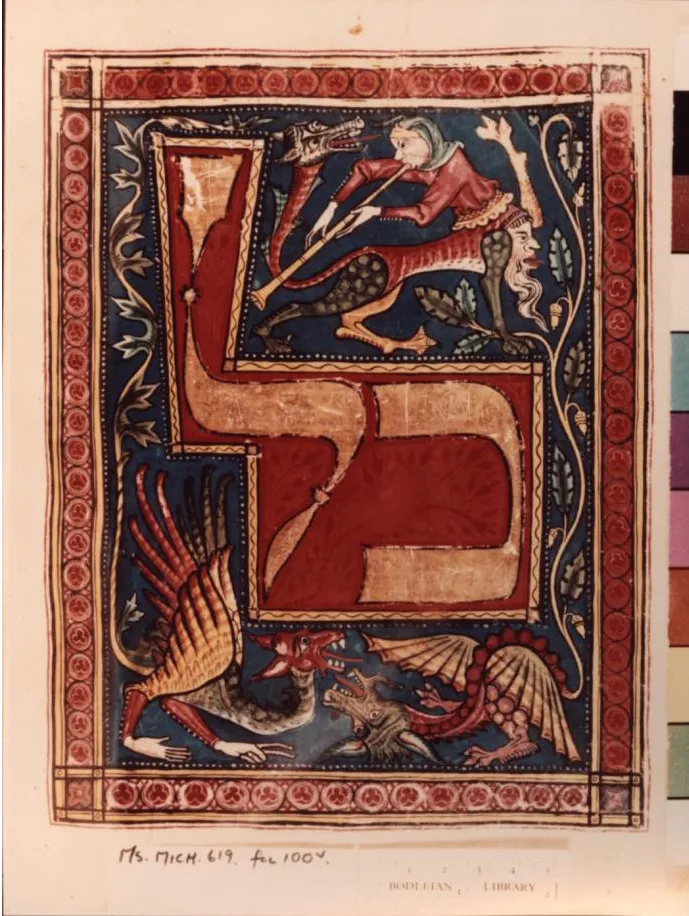

With more than 260,000 entries, the index is the world’s largest digital collection of Jewish art, according to Claire Voon of Hyperallergic, who first reported on the project. Spanning from antiquity to the present day, the index catalogues everything from ancient Judean coins, to 14th-century Hebrew manuscripts, to drawings by contemporary Israeli artists. The index is divided into six categories—Hebrew Illuminated Manuscripts, Sacred and Ritual Objects, Jewish Funerary Art, Ancient Jewish Art, Modern Jewish Art and Jewish Ritual Architecture—but it is also searchable by object, artist, collection, location and community.

Hebrew University researchers have been building this expansive repository for more than 30 years. The project was established in the 1970s by the late Bezalel Narkiss, an Israeli art historian who wanted to create a catalogue of Jewish iconography similar to Princeton University’s Index of Christian Art (now known as the Index of Medieval Art).

In total, the Index features items from 41 countries, and for decades now, the Center for Jewish Art has been sending groups of researchers and graduate students on documentation trips around the world. After Israel signed a peace treaty with Egypt in 1979, for instance, Israeli researchers raced to Cairo and Alexandria to catalogue the synagogues and ritual objects used by Jewish communities that once thrived there. When the Iron Curtain fell, teams were deployed to previously inaccessible areas of Eastern Europe.

Over the years, the project has expanded—“It's not only an iconographical index,” Levin explains, “it's also a repository for Jewish built and visual heritage in general”—and taken on an increased sense of urgency.

“Our center is running against time,” Levin says, “because we try to catch up with things that are in danger of disappearing.”

Although the documentation teams primarily focus on photographing, sketching and detailing at-risk structures and sites, researchers sometimes work with local communities to encourage the preservation of Jewish historic objects. When Levin traveled to Siberia in 2015, for instance, he came across a small museum in the remote republic of Buryatia that housed a substantial collection of Jewish ritual objects.

“They never understood what to do with them,” Levin says. So he visited the museum on three separate occasions to educate staff about what the objects were, and how they functioned. After Levin went back to Israel, the museum staged a small exhibition of Judaica.

“Jewish heritage belongs not only to Jews,” Levin says. “[I]t's part of the local landscape, it's part of the local culture.”

Local culture has a significant influence on historic Jewish communities, as the index shows. Browsing through the database reveals synagogues, cemeteries and artworks modeled after a range of artistic and architectural traditions, such as Byzantine, Gothic, and Baroque.

“Every object is connected to its place of production, and to the stylistic developments in this place,” Levin says, but adds that Jewish art is also “influenced by Jewish objects from other places.” Religious spaces built in the style of Portuguese synagogues crop up in Amsterdam, London and the Caribbean, Levin notes, and Hebrew texts printed in Amsterdam can be found across Eastern Europe.

Now that the index is online and its entries are easily accessible, Levin says he hopes visitors to the website will be “impressed by the richness of Jewish culture, and by interconnection between different Jewish diasporas.” Levin also plans to continue expanding the database through additional documentation trips, along with some other, less conventional methods.

“I tried to convince somebody that illustrations from Hebrew manuscripts can be good [inspiration for] tattoos,” Levin says with a laugh. “They didn't do it— unfortunately, because I [wanted to] document this person as an object of Jewish art.”