17 Billion Earth-Size Planets! An Astronomer Reflects on the Possibility of Alien Life

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/20130111092026planets.jpg)

Though we may not find life on Mars, a new study shows that we still have at least 17 billion other chances. Astrophysicist Francois Fressin recently led a team of researchers at the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics in analyzing three years of data from Kepler, a space observatory launched in 2009 to discover Earth-like planets, and found that one in six stars in our galaxy is orbited by a planet roughly the same size as our own.

Kepler collects data by monitoring instances of periodic dimming in the light emitted from more than 160,000 stars. These tiny eclipses, if regular, suggest the presence of planets in orbit as they cross the stars’ centers. The technique is not foolproof, though. Of close to 2,700 planetary candidates identified in Kepler’s three years of observation, scientists were unsure of how many were bona fide Earth-size planets and how many were false positives—two stars themselves crossing, for instance, or other factors that produce similar dimming effects.

Fressin’s job was to find a way of vetting Kepler’s results to determine the observatory’s accuracy. “It requires some work,” he says. “What we are doing is a simulation of all the astrophysical configurations we could think of that could mimic a planet.”

By imagining all possibilities of what could not be Earth-sized planets, that is, Fressin and his team devised a formula to predict what percentage of potential planetary candidates actually are planets. His simulation showed that imposters only could account for 9.5 percent of the candidates, which suggests that the remaining 90.5 percent are real.

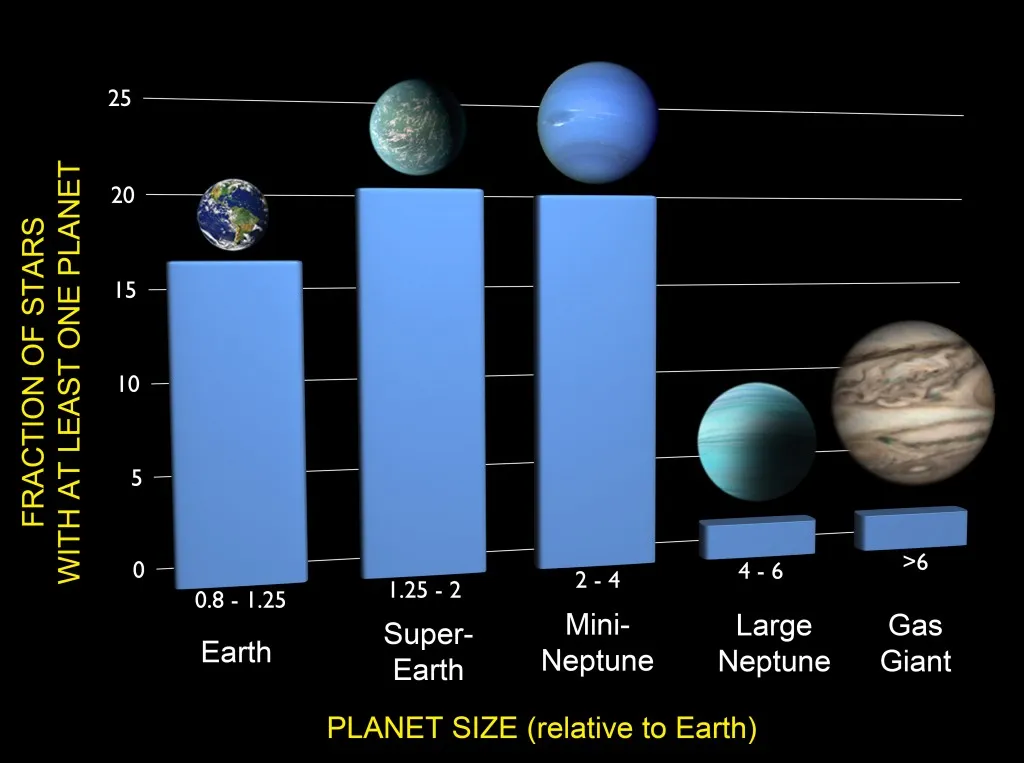

Based on the roughly 100 billion stars in the Milky Way, Fressin was able to estimate that about 17 percent of the stars in our galaxy—a whopping 17 billion—have an Earth-size planet orbiting within the same distance as Mercury to the sun. He reported his team’s findings on Tuesday, just a day before another group of astronomers from the University of California, Berkeley, and the University of Hawaii at Manoa announced nearly identical findings.

This result is a big deal, Fressin says, because it allows scientists to assert for the first time with any certainty that Kepler is reliably recording the occurrence of small planets, and it demonstrates that we are far, far from being alone in our planetary size in the galaxy—an affirmation that gives us a glimpse at just how many possibilities there are for extraterrestrial life.

“It’s very difficult to know what to look for when we look for another life,” Fressin says, because we know of only one example—our planet. He explains that larger gaseous planets appear too volatile and smaller planets seem not to have enough atmosphere to support living creatures, so scouring our galaxy for like-sized planets probably is our best bet if we ever hope to find aliens.

This question of whether or not life exists elsewhere in the universe is what drives Fressin’s research. Though he admits that both possibilities are “scary,” he views the process towards discovery as essential to our self-understanding. In life, “you can’t really know yourself without contact with others,” he says. “You can’t really know the country in which you dwell if you haven’t visited other countries. I’m under the impression that it could be the same for what living as inhabitants of the Earth means. You need to know about the other worlds.”

Fressin mentions that he is “optimistic” that researchers will find signs of extra-terrestrial life in the “maybe-not-so-distant-future,” but cautions that finding life similar to ours is a much greater challenge: “It’s the question of whether we will find evidence of intelligent, advanced civilizations that is tougher to answer.

“But the small steps are worth taking,” he says.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/paul-bisceglio-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/paul-bisceglio-240.jpg)