A Rare Public Display of a 17th-Century Mayan Manuscript

With the book newly digitized, scholars are reinterpreting a story of native resistance from within its pages

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/2e/0c/2e0ccf93-7a1d-4e3c-8a02-23cb374557f9/img0167web.jpg)

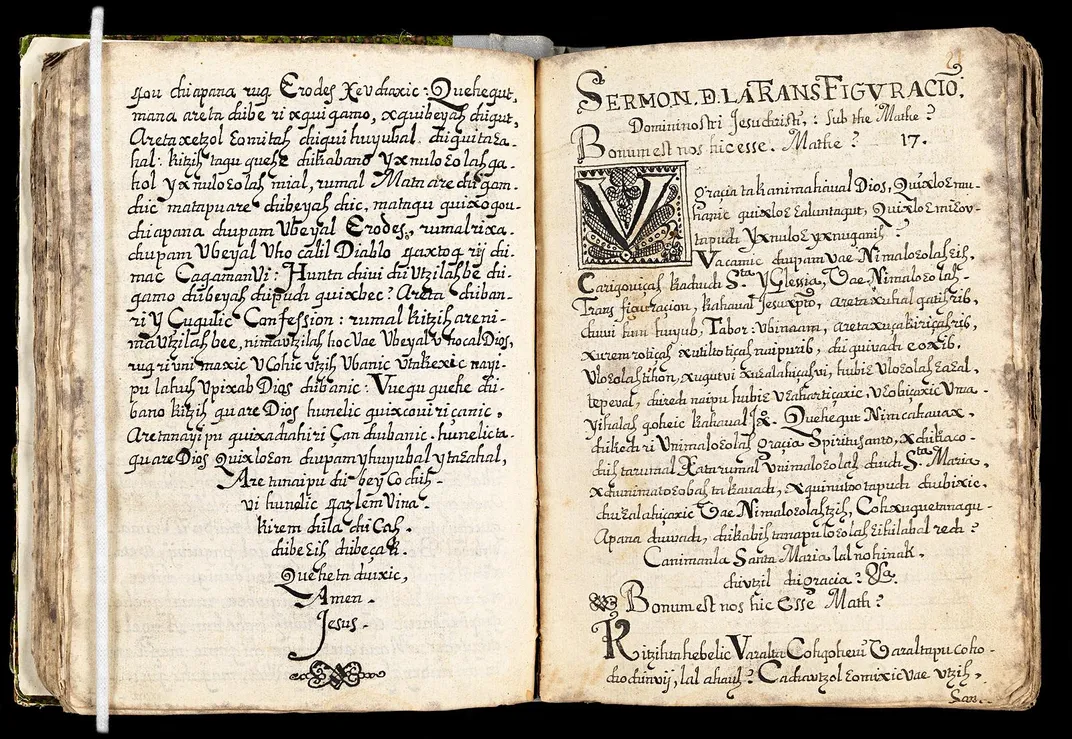

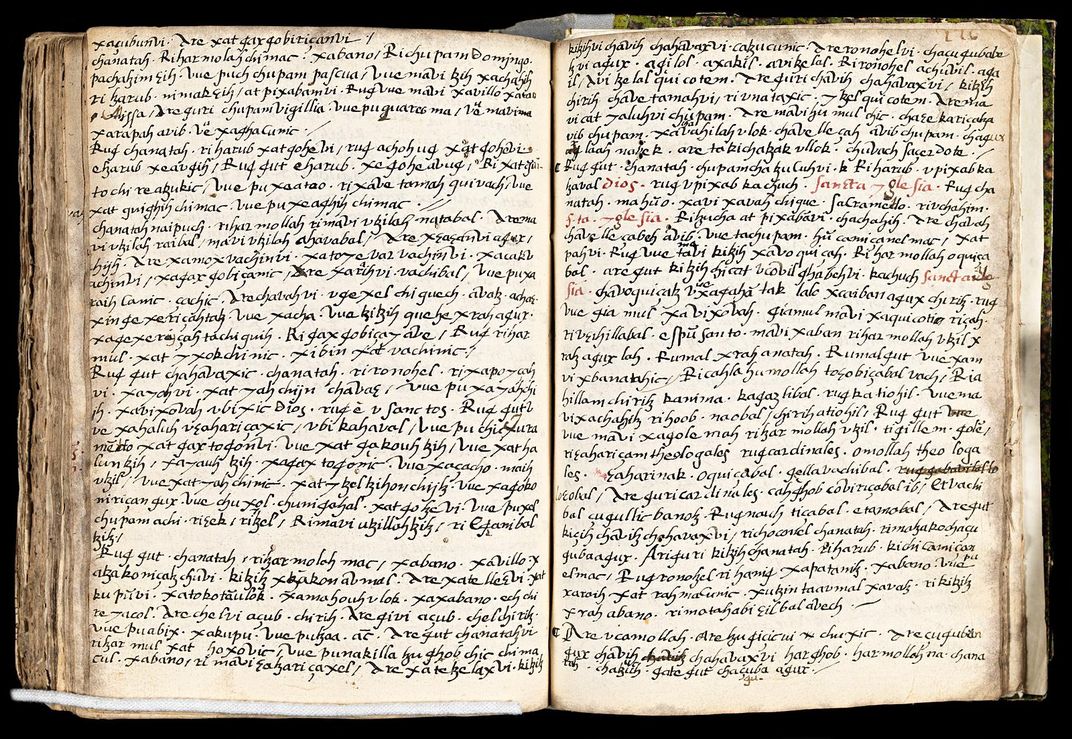

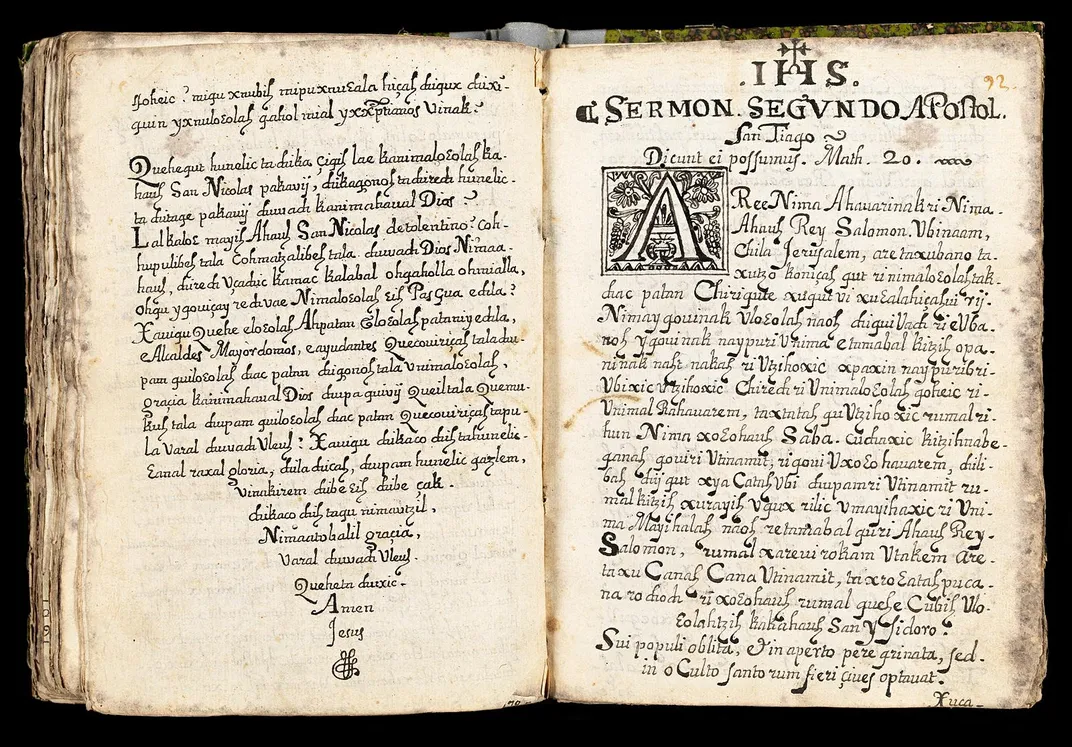

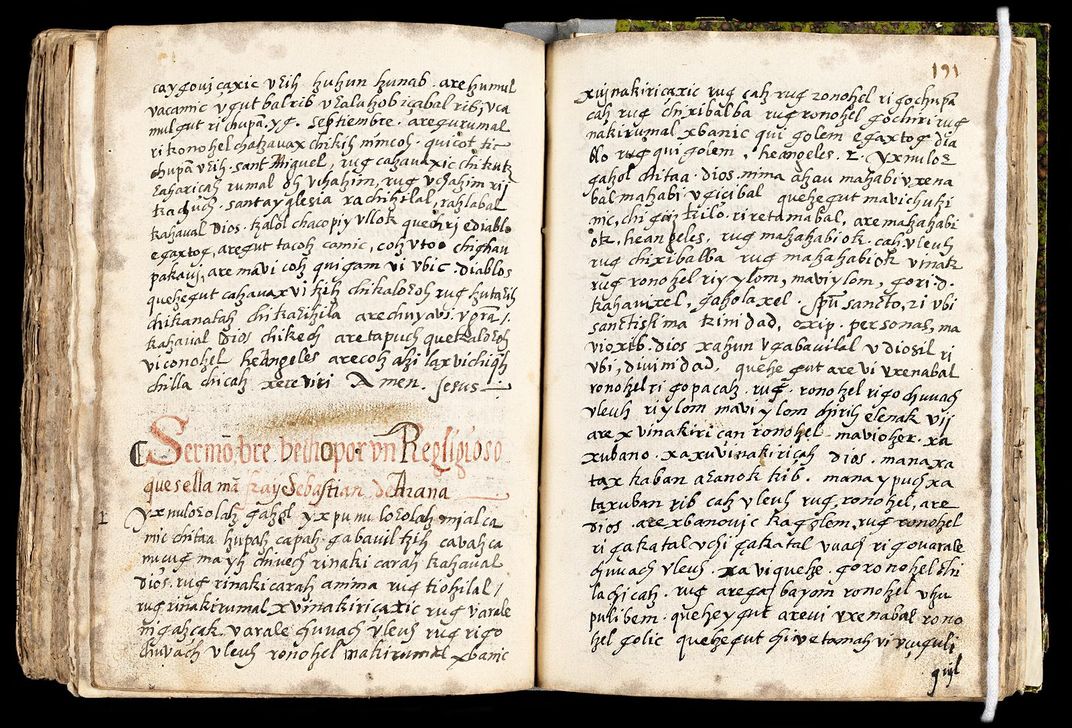

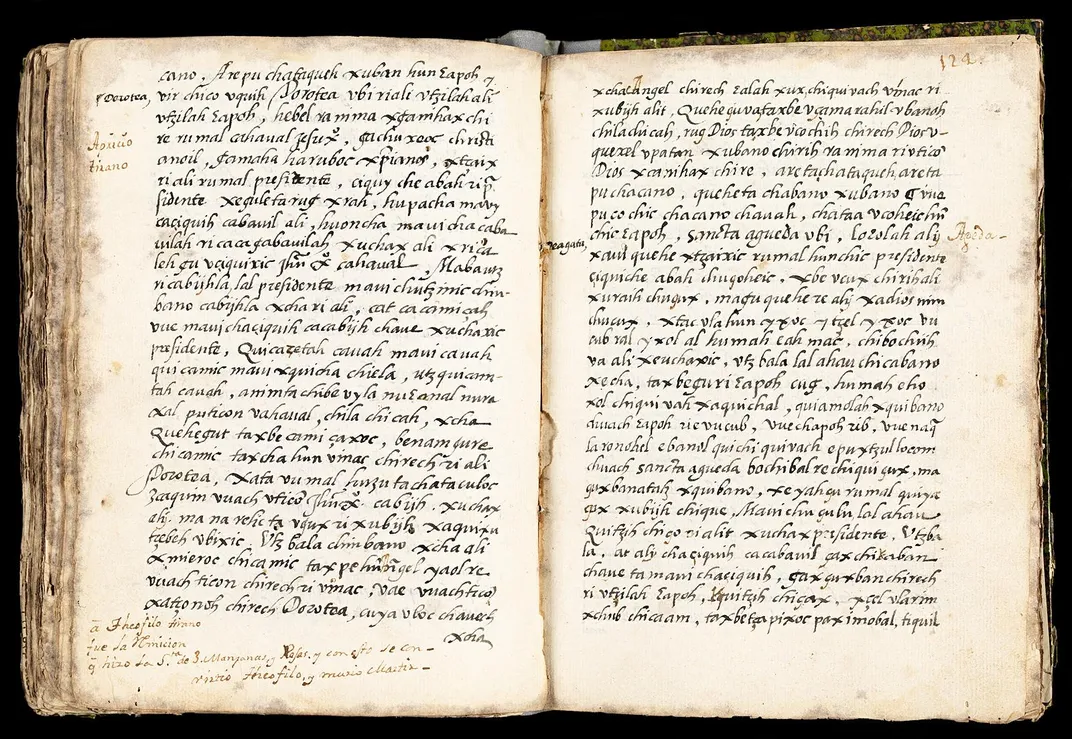

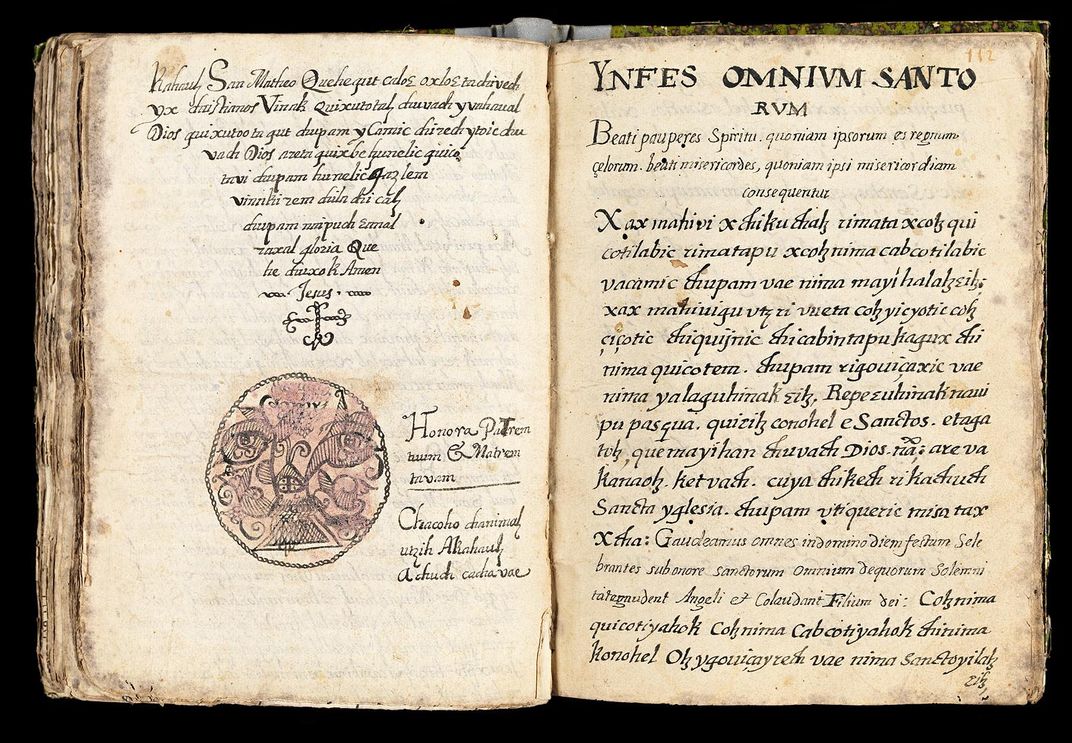

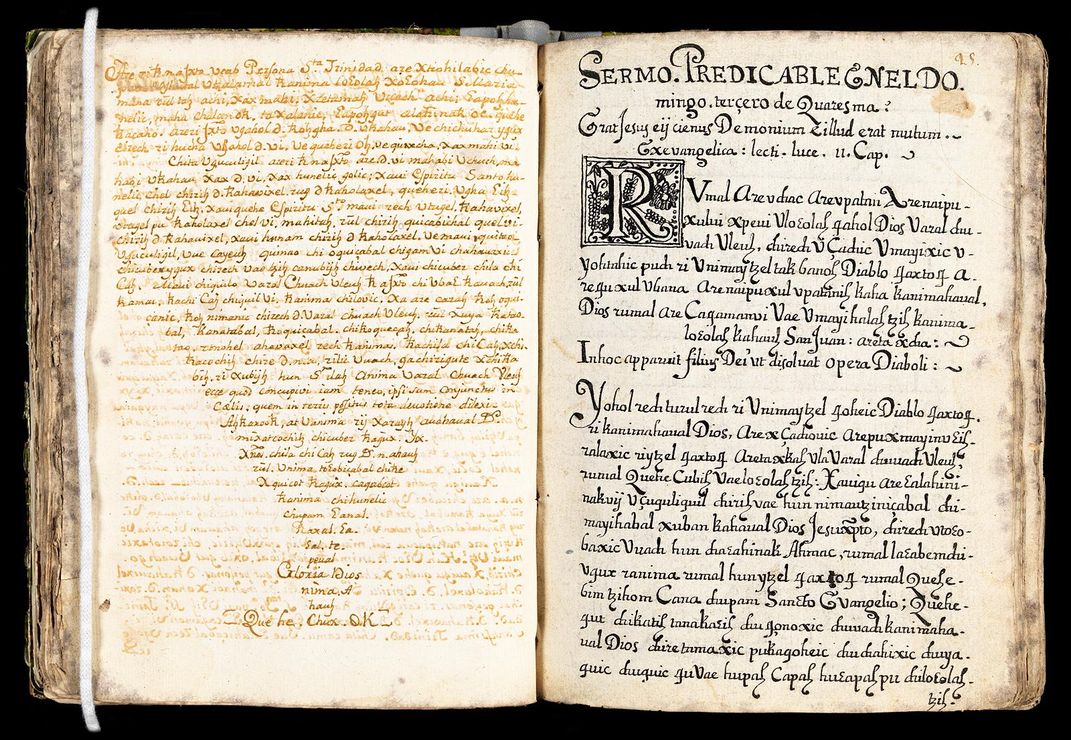

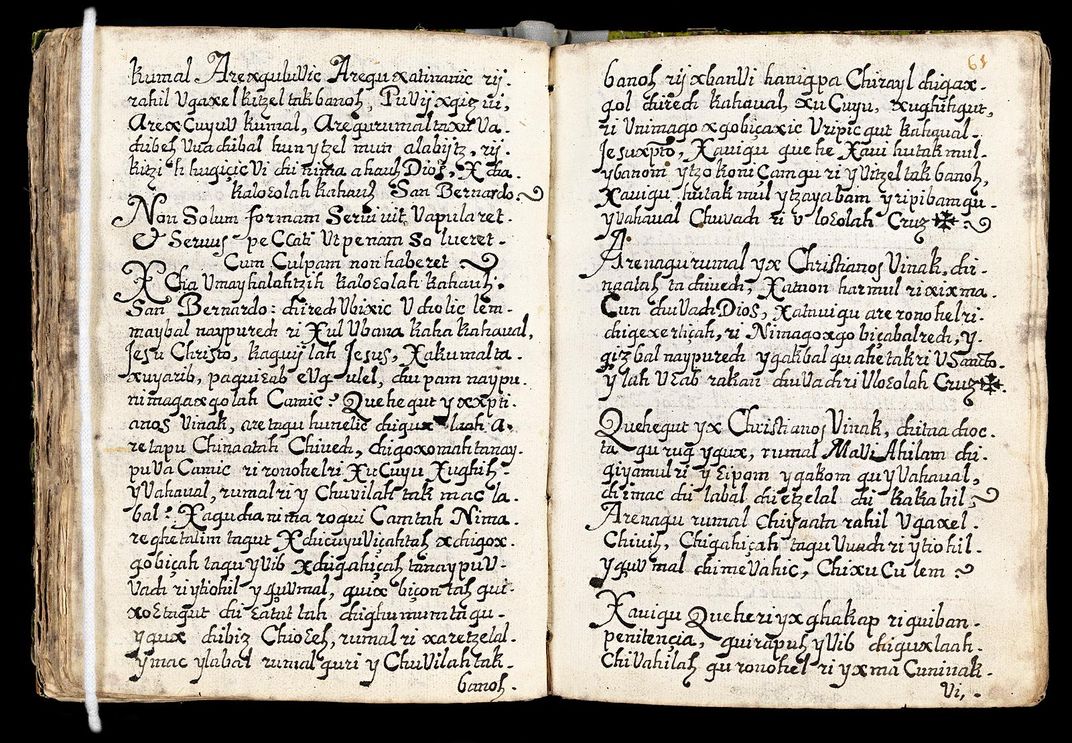

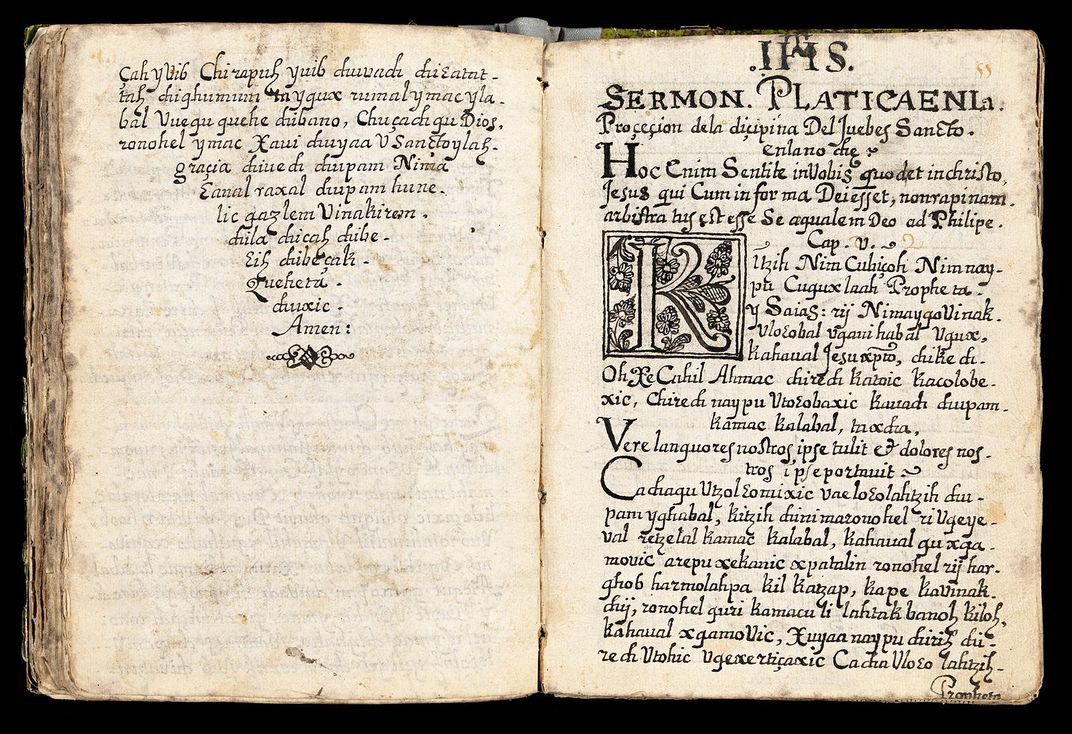

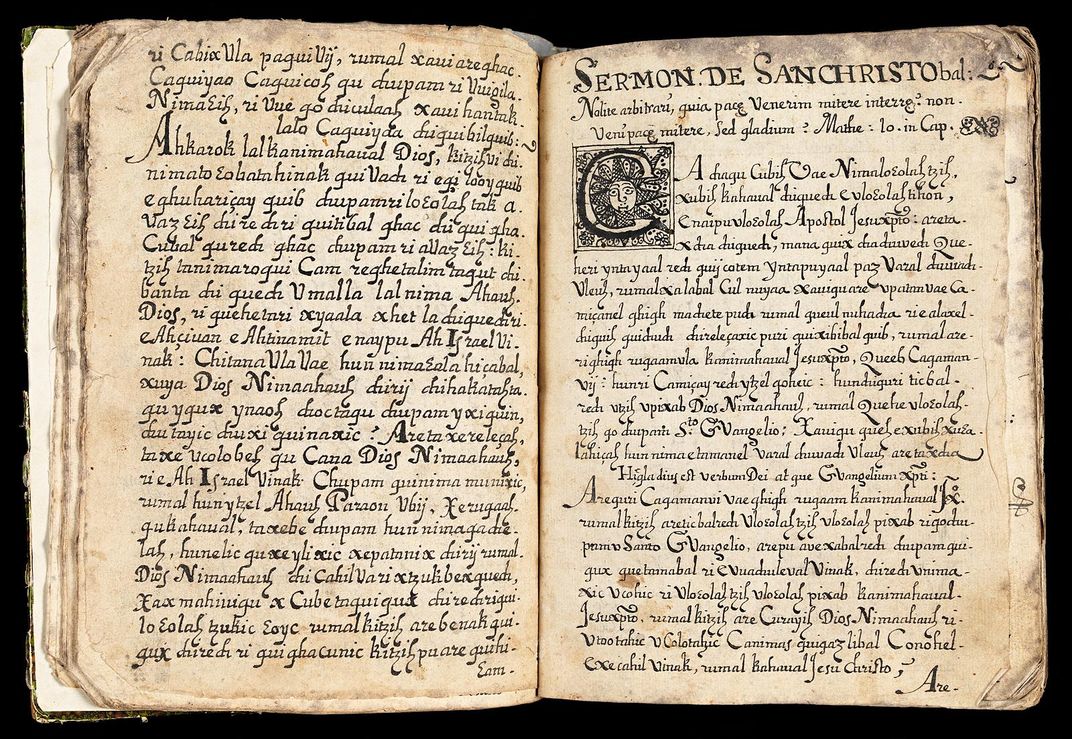

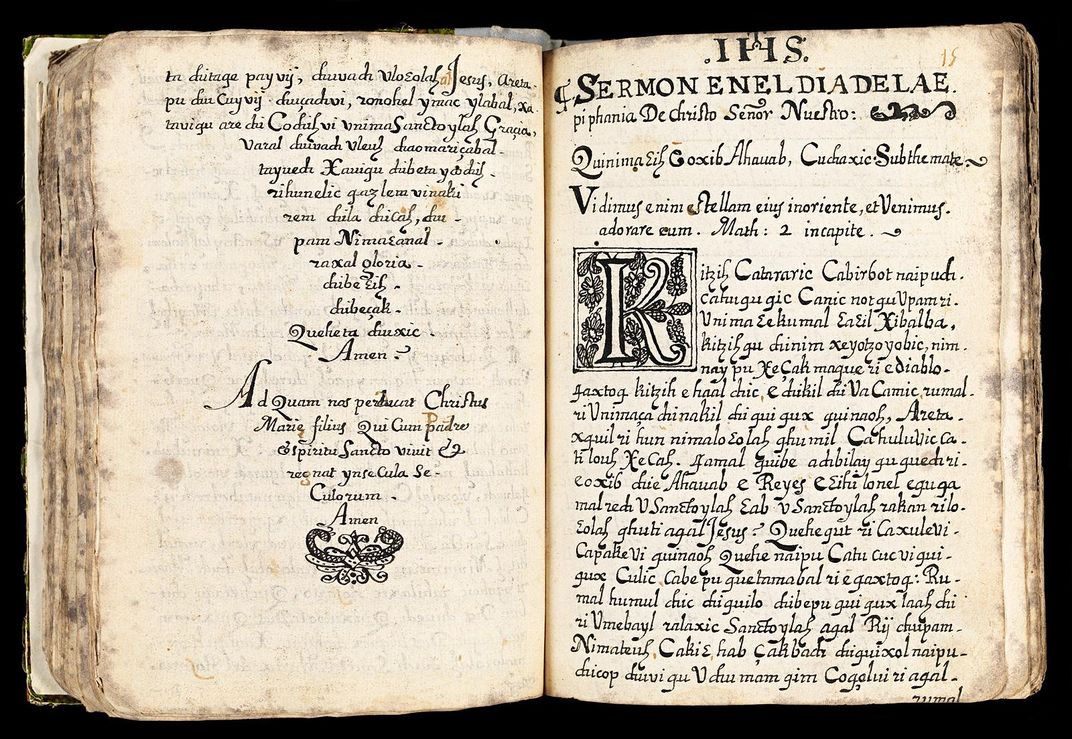

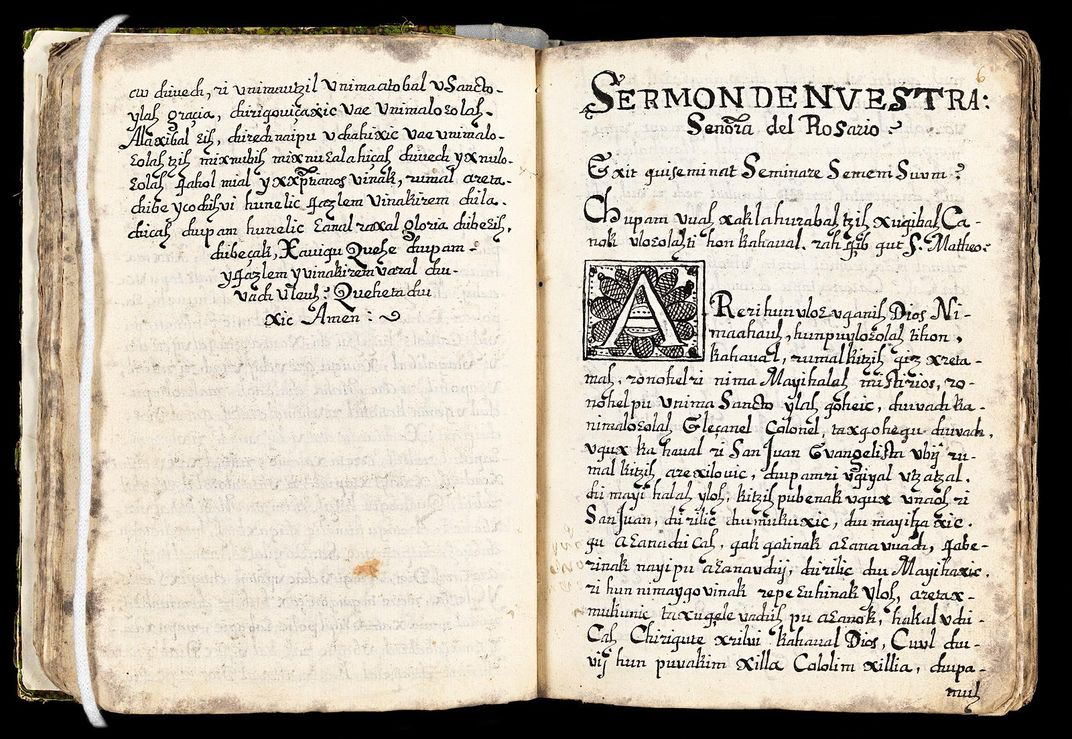

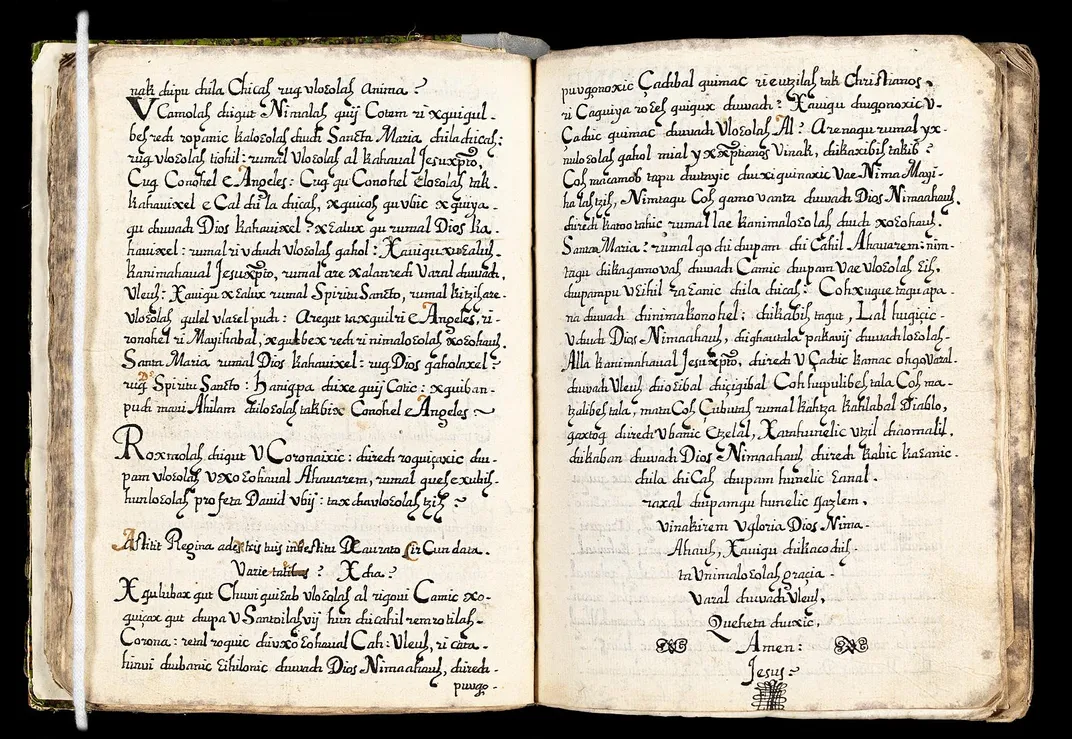

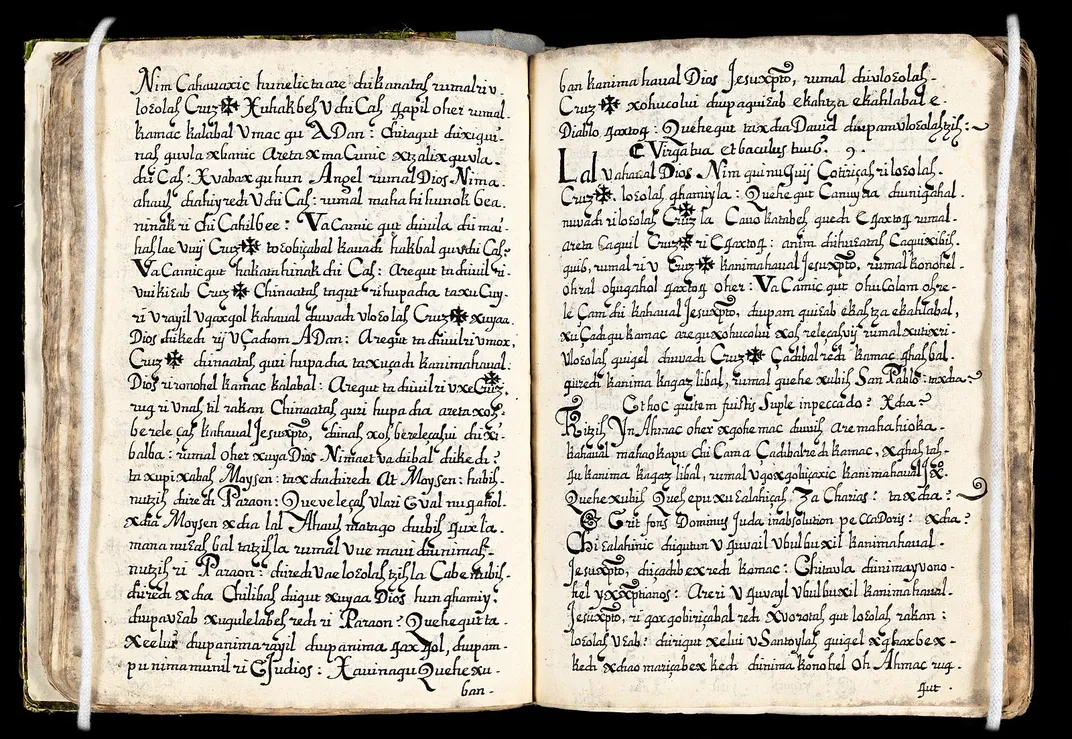

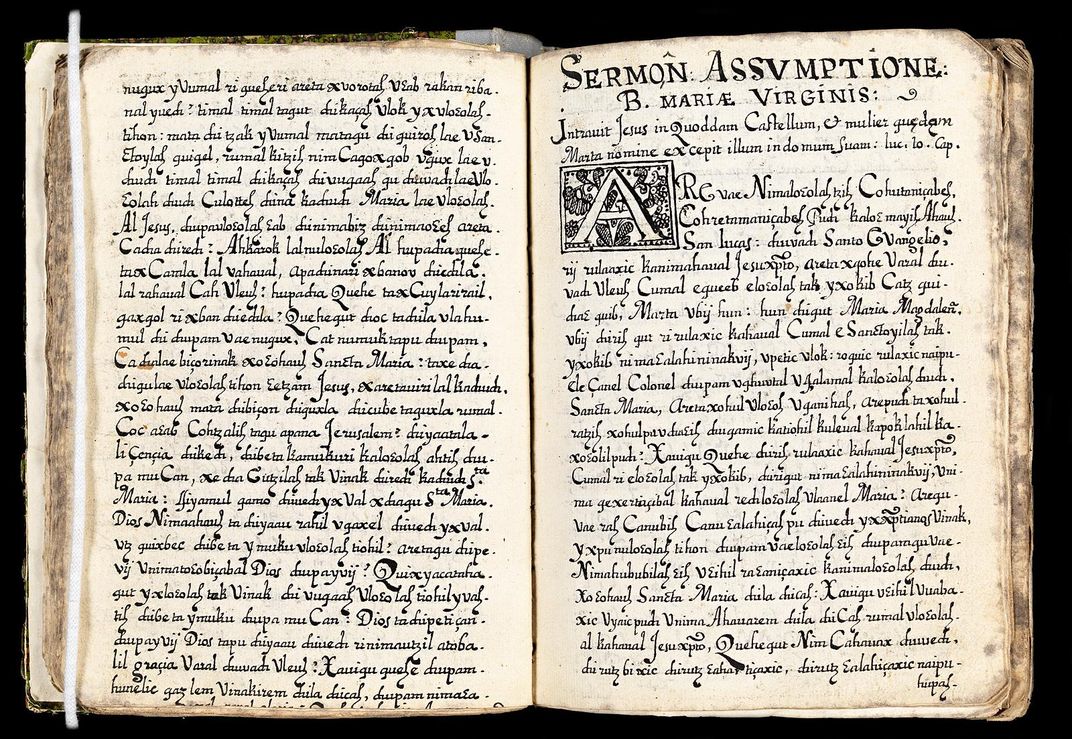

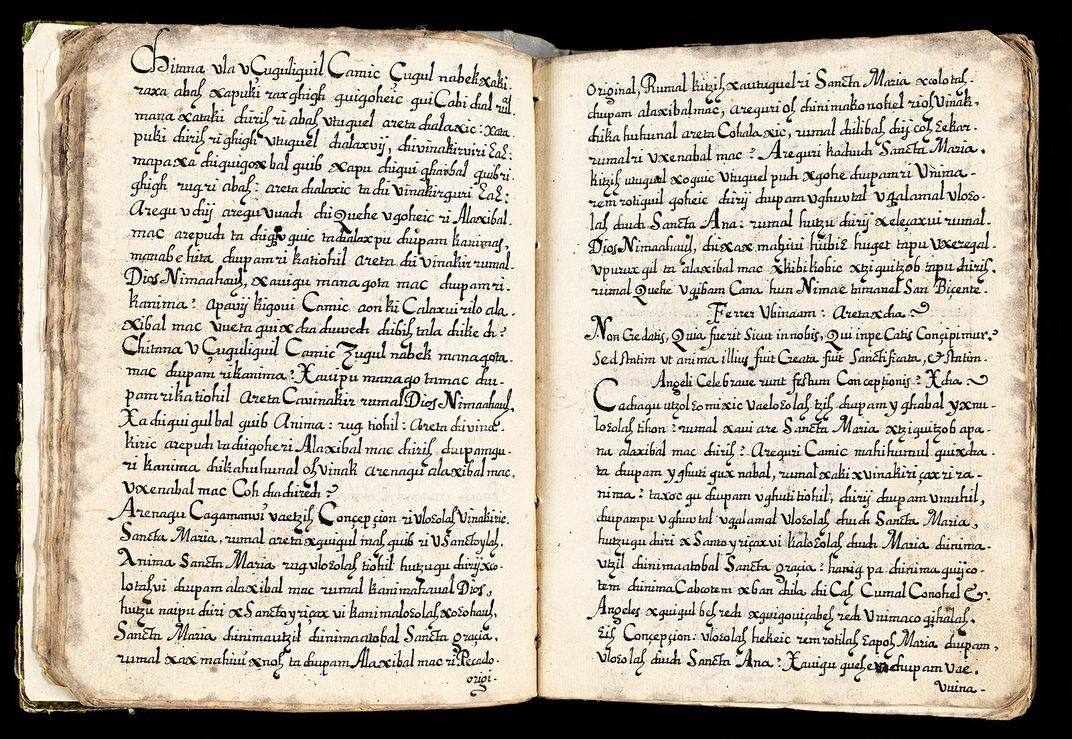

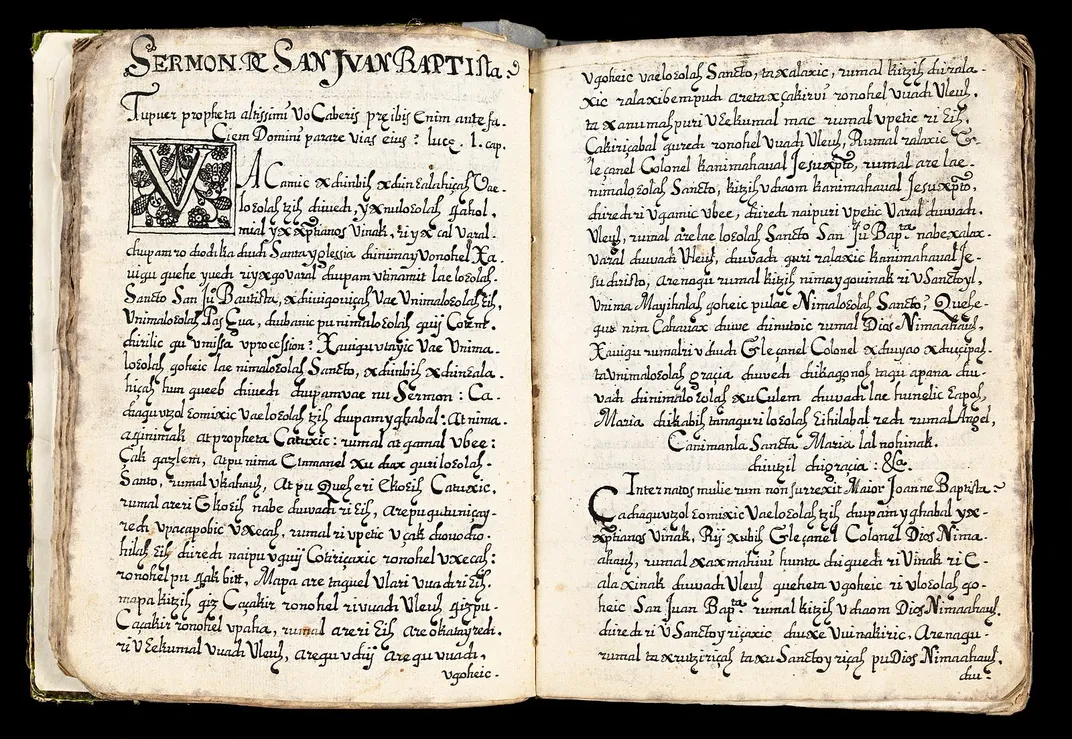

When you take a close look at the flowery but meticulous lettering in the 17th-century book, you can see that many people wrote the script, at different times. The book includes everything from sermons to poems, and there’s a dedication to Pope Urban IV.

The Libro de Sermones Varios en Lengua Quiche, from 1690, is the oldest manuscript in the collection of the Smithsonian’s National Anthropological Archives. It provides not only a fascinating look at the evolution of the Maya K’iche’ language, but it also tells a stark tale of religious history.

“When I see a document like this it just blows me away to see the care with which the language was put on paper by so many different people,” says Gabriela Pérez-Báez, curator of linguistics in the anthropology department at the National Museum of Natural History. She says the book is written in four different languages, including K’iche’, Latin, Spanish and Kaqchikel. “The paper is thicker, the book smells differently, it is really amazing to see the care with which it was written,” Pérez-Báez marvels.

The Libro de Sermones is part of the Objects of Wonder exhibition now on view at the National Museum of Natural History. The book has also been digitized so that scholars can peruse the book both to answer questions about history, but also to document the changes in the K’iche’ language as the Spanish were taking over the Maya empire in the 16th century. The text in the Libro de Sermones is very similar to the K’iche’ language that was spoken before contact with the Spanish. The book was given to one Felipe Silva by Pablo Agurdia of Guatemala in 1907, and Silva apparently donated it to the Smithsonian Institution sometime after that, but there are no documents explaining exactly how that happened. Today, Pérez-Báez says the book is quite relevant and important to scholars.

“K’iche’ is a Mayan language which dates back several thousand years. It certainly precedes Spanish by hundreds of years. It is a language which is spoken in Guatemala, so Mayan languages are still in use across what is now Guatemalan Mexico and have spread as far as the Northern third of Mexico. But otherwise they are concentrated in Mesoamerica—the South of Mexico and in a little bit of Central America, Guatemala and so on,” Pérez-Báez says. “Languages change naturally, but they also change when they come into contact with other languages. . . . Once contact with a Colonial language becomes very intense . . . the influence of a language like Spanish on indigenous languages is greater and greater over time.”

K’iche’ is spoken today by more than one million people, and thousands of K’iche’ speakers now live in the United States, according to Sergio Romero, a professor in the department of Spanish and Portuguese at the University of Texas at Austin.

“Lots of migrants, especially in the last two decades, are K’iche’ speakers. I am often called to translate on behalf of K’iche’ speakers who don’t speak Spanish,” Romero says, adding that K’iche’ is one of 33 different Mayan languages. “There are different dynamics to each of these 33 languages, and each of them has a lot of regional variation. So between K’iche’ and Ixil, another Mayan language, there is as much difference as between English and . . . Hindi.”

Romero says one of the reasons the Libro de Sermones is important, is that in the 19th century around the time of Guatemalan independence, K’iche’ lost its status as the official language in the region. But there are many documents including wills, land deeds and various sorts of chronicles and other texts written in K’iche’ from the 16th and 17th centuries. There are also pastoral texts, catechisms and confessionals used by priests to both learn the language and try to convert the K'iche.’

But Romero says the K’iche’ resisted being converted to Catholicism, and there is evidence of that in the book, which he says is a “crucial” tool in illustrating that fact.

“It’s the way in which the K’iche’ were able to cope with the Spanish invasion and the Christian invasion . . . . They didn’t assimilate,” he says. “What they did was appropriate certain elements of Spanish culture to be able to adapt and defend and protect their own spaces of political and cultural sovereignty. So K’iche’ religion today is really a hybrid religion that has elements of Spanish origin and elements of Christian origin and this document shows that very well. You can see how certain words were actually bent by the Spanish to be able to convey certain meanings and you can see how those certain words were interpreted in a different way by the K’iche.’”

Romero points to the word mak, which is used today to reference sin, as in Christian sin. But in the 15th century it meant ‘will,’ as in your will to do something. Sin, Romero says, didn’t exist as a concept to the K’iche’ because they were not Christian. Dominican missionaries took that particular word and shifted its meaning so it could be used to convey the theological notion of sin.

“The only way to resist was to adapt,” Romero says, “but the adaptation was not decided upon by the Spanish.”

He adds that even today, the Catholic hierarchy in Guatemala still cannot accept the fact that Christian practices among the K’iche’ are simply different than those of non-indigenous Catholics. Romero says the K’iche’ religion of today is the result of this “interesting dialogue” between Dominican missionaries who wanted to impose a certain brand of Catholicism and the K’iche’ who just picked whatever was interesting and useful to them.

The Smithsonian’s Pérez-Báez, who was raised as a Catholic in Mexico City, explains that even in an urban Spanish environment children are taught that one must be a good person, or they will burn in hell. She is not a K’iche’ expert, but Pérez-Báez thinks that the sermons in this book likely contain similar rhetoric that was used to coerce people into converting to Christianity.

To her, Libro de Sermones is a reminder of what she calls the brutally violent mandatory conversion to Catholicism. The Spanish colonization involved forced labor, and the Mayas who refused to give up their original religion were often jailed and tortured for heresy. Maya artifacts were deliberately destroyed, and most of their sacred texts were burned. Pérez-Báez says the book was likely produced by native speakers of K’iche’ whose original, indigenous names had already been replaced with Spanish names, who were being converted against their will.

“To me, being an advocate for linguistic diversity in this respect of human rights, it’s very difficult to hold a document that was an important part of the conversion to Christianity and all of the abuses. This book was representative of an era during which colonialism and the associated conversion to Christianity oppressed the indigenous population in often violent ways,” Pérez-Báez explains.

She is also disturbed by the thought that native speakers of K’iche’ were hired, or used, in the production of a book that was being used as an instrument to force the conversion of the remainder of the K’iche’ population.

“This is evidence of that conversion process that was very damaging to the languages, the cultures, the local knowledge, but especially the physical and emotional well-being of the people,” Pérez-Báez says.

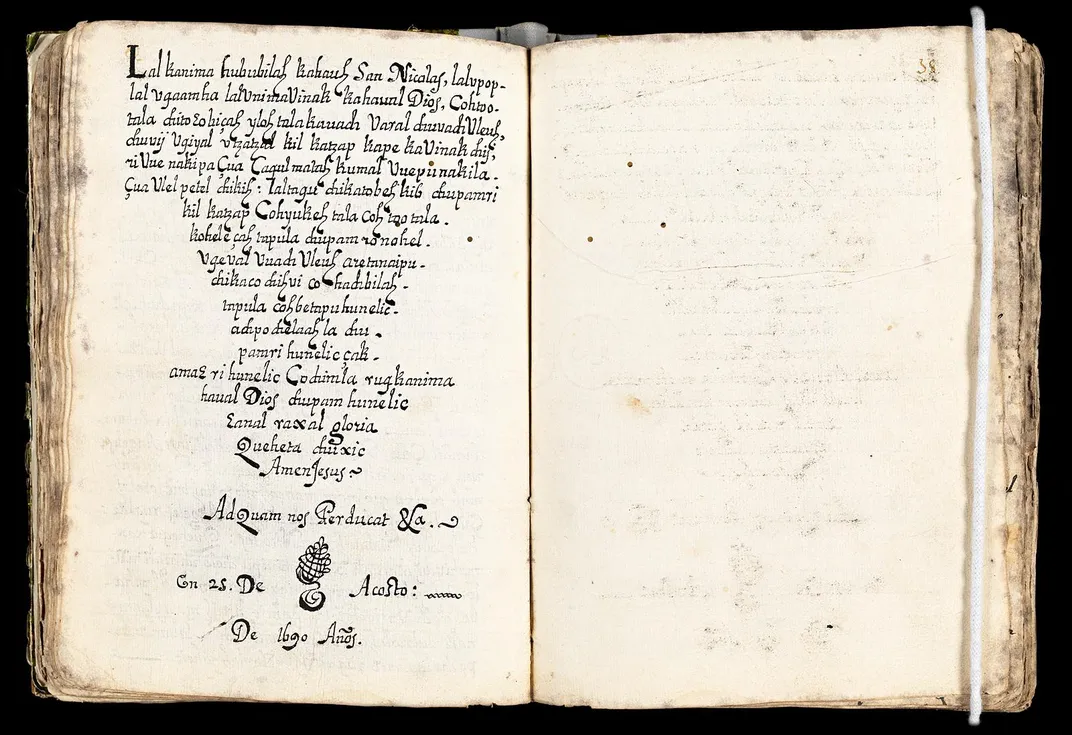

Both she and Romero think the digitization of the Libro de Sermones is vitally important for scholars, even though the ancient text had to be laid nearly flat page by page to get a good digital image. Pérez-Báez says the book has gone through conservation, and is in pretty good shape for the Wonder exhibition. Allowing access to the document to scholars around the world is critical, Romero says. It also makes for better preservation.

“We’ve gotten to a different age in the study of colonial manuscripts of indigenous languages. … For us, having access to these manuscripts online is crucial because we need to have concordance between different text,” says Romero. He explains that sometimes a particular text doesn’t have the full story. That means scholars then have to consult different documents being reviewed by other colleagues that may include the missing fragments.

“Many libraries are actually digitizing their manuscripts and making them available online for scholars. . . . It allows us to work across political lines and borders. . . . So now we can use digital copies of manuscripts to be able to work together on the same text and that makes for a much more rich and interesting dialogue.”

“Objects of Wonder: From the Collections of the National Museum of Natural History” is on view March 10, 2017 through 2019. Funding for the digitization of the Libro de Sermones was provided by the museum's Recovering Voices Program.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/allison.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/allison.png)