What a 1950s Fashion Maven Might Teach Us About What To Wear

When it was time to suit up for work, politics or social engagements, Claire McCardell’s fans embraced her chic, but comfortable style

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/5d/37/5d37e838-7fe1-4b51-8b04-e4ea6964cd42/p141suitjn20143611web.jpg)

Today, critiques are numerous of “fast fashion,” which tends to bolt from the runway to mass outlets to American closets to Goodwill (or third-world countries such as Zambia as quick as a Big Mac is slapped on a bun.

Both fast food and fast fashion offer short-term consumer benefits, but have long-term consequences. For consumers of cheap, high-fat, low-nutrient meals, the cost is health, vitality and arguably, a sophisticated palate. For buyers of inexpensive, poorly made garments, the sacrifices are similar: unflattering fit, poor durability, and arguably, good taste. Still, as journalist Elizabeth Cline points out in her book Overdressed: The Shockingly High Cost of Cheap Fashion, many Americans now prefer rapid wardrobe turnovers. Inexpensive, shoddily made clothing with flash-in-the-pan design details has become the norm.

Not all clothes-lovers rejoice. Some consumers press for socially conscious shopping alternatives that fully disclose their labor practices and manufacturing costs. Companies like Everlane tout “radical transparency” alongside sleek style and high quality. And some fashionistas simply limit themselves to classic, well-made, enduring styles, opting for a versatile minimalist approach to avoid the time suck of endless novelty-seeking.

Opposition to trendy impracticality in fashion is nothing new.

Decades ago, amidst the Great Depression and World War II, an innovative American designer named Claire McCardell (1905-1958) helped craft a sartorial philosophy in favor of a long-lasting, versatile, and attractive wardrobe.

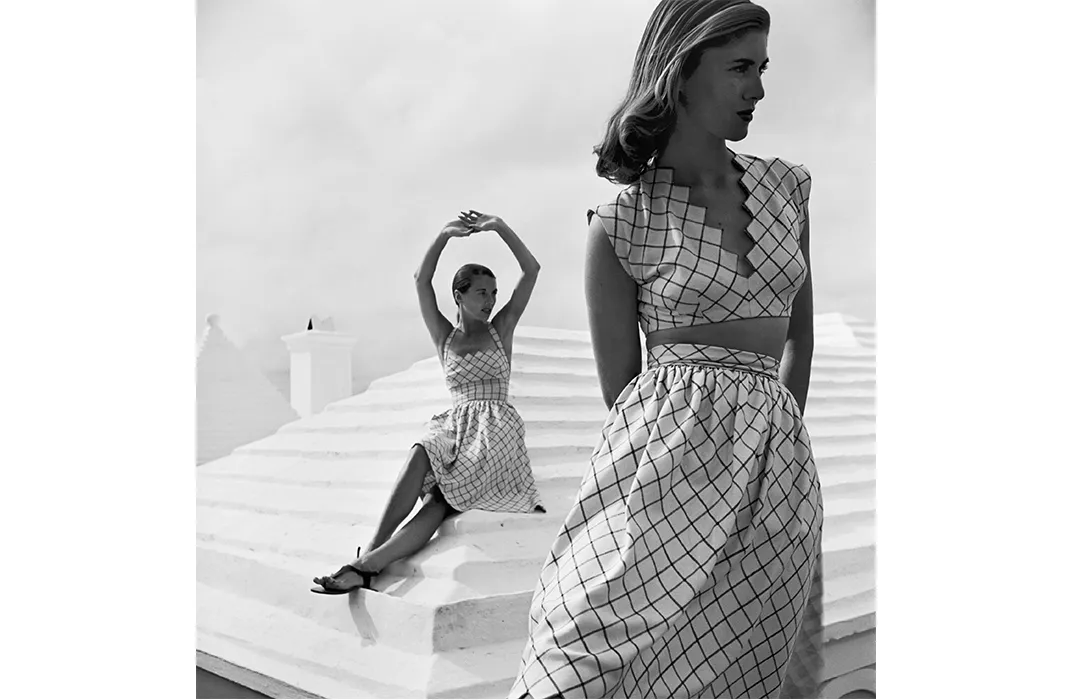

A groundbreaking maven of women’s sportswear and one of America’s first globally recognized designers, McCardell encouraged the desire for chic, sensible styles. The urban pace of 1920s America, the advent of modern dance and broadening approval of feminine athleticism helped set the stage for McCardell’s functional “American Look.”

Her clothes with roomy, dolman-sleeved jackets, skirted business suits, cotton bathing wear and denim, midriff-flashing playsuits, defined a new style of practical, energetic femininity. A major innovation, the American Look (pioneered also by the New York City-based Vera Maxwell) was the concept of interchangeable wardrobes, comprised of mix-and-match pieces that emphasized long-lasting wearability at a democratic price. Without sacrificing style, the "Look" rejected the expensive formality and high-maintenance of French garments. In her 1955 book What Shall I Wear?: The What, Where, When and How Much of Fashion, McCardell reminded her fans that “casual never means careless.”

By the time McCardell designed the c. 1950s gray, wool blend suit held in the collections of Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History in Washington, D.C., she had 20 years of design renown under her belt. The suit will go on view in the upcoming exhibition, “American Enterprise,” as part of the “The Consumer Era, 1940-1970” display, alongside items from businesswoman Brownie Wise’s Tupperware sales parties, examples of Ruth Handler’s iconic Barbie Doll merchandising, and copies of Charm magazine, launched in 1950 as “the magazine for women who work.” These artifacts show, as historian Joanne Meyerowitz has demonstrated her seminal 1994 Not June Cleaver: Women and Gender in Postwar America, 1945-1960, that women did not suddenly quit working outside the home when the war ended, but rather expanded their public, political and social roles.

McCardell’s suit is doubly representative of women’s rise in business during this period. Contrary to prevalent tightly tailored June Cleaver stereotypes, women sought out comfortable, versatile business apparel, especially as more mothers than ever before (30 percent by 1960) took on paying jobs in addition to domestic responsibility. The success of Claire McCardell herself, starting at a time when “fashion” and “French” were almost exclusively synonymous and female entrepreneurs oddities, illustrates the changes in the global fashion networks as well as in women’s lives.

Honing her sartorial voice during the Great Depression, McCardell translated the ease, affordability and comfort of sportswear into daily costumes appropriate for work, school and casual recreation. She was able to design for the modern woman in large part because as she claims, her ideas “come from trying to solve my own problems.”

Women’s lives were newly full of action and movement, whether they worked in a city, cared for a large family or left home for a higher education. College-bound women were a rapidly expanding audience during McCardell’s reign. The percentage of 18-to-20-year-olds attending college rose from 8 percent to 30 percent between 1920 and 1950, and continued to rise in the postwar years. As historian Deirdre Clemente reports in her book Dress Casual: How College Students Redefined American Style, the young women in this demographic were tastemakers. Their love of casual sportswear like McCardell’s set the standard.

Although McCardell did work and study in Paris in the 1920s, and was very influenced by the work of Madeleine Vionnet, she is remembered as the quintessential American designer, innovative in her refusal to mimic revered Parisian designers.

After her sojourne to France, she rose to prominence working for the New York City-based Townley Frocks, where she developed unique signature touches—McCardellisms, like her clever brass hook fasteners—and soon had her name on the label, a rarity outside of French couture. Before 1940, most U.S. designers worked without recognition or authority, replicating Paris designs for ready-to-wear manufacturers serving middle-income buyers. However, according to historian Rebecca Arnold, author of the book The American Look: Fashion, Sportswear and the Image of Women in 1930s and 1940s New York, a few Depression-era department stores began to promote domestic designers.

In 1932, Lord & Taylor vice-president Dorothy Shaver—herself a groundbreaking businesswoman—flouted tradition, giving American designers premiere real estate in prominent window displays. The “American Designers’ Movement” helped cultivate consumer recognition of homegrown talent, including McCardell.

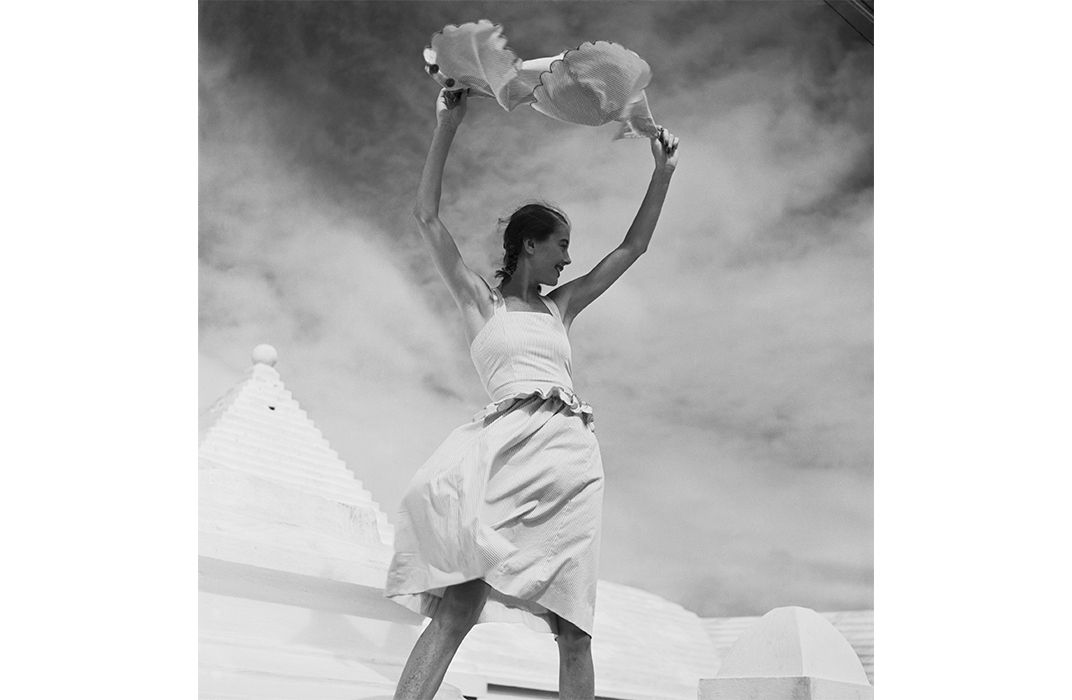

World War II offered on-the-rise American designers a bigger piece of the market pie. In 1940, Nazi occupation halted the annual jaunt to the Paris haute couture fashion shows. With French products inaccessible and patriotism on the rise, New York City became the new fashion focus, both at home and abroad. The war changed not only who made fashion, but how they made it. Rations on materials used in war manufacturing and soldier’s clothing, like leather and wool, posed challenges for clothes makers.

Stepping up and keeping true to her philosophy of comfort, McCardell invented her signature Capezio flats. Their simplicity saved leather, and their dance-inspired flexibility meant unparalleled comfort.

After the war’s end, some Americans reverted back to former habits of sanctifying French fashion, a move exemplified by the popularity of Christian Dior’s New Look—a slim-waisted style that June Cleaver might wear while vacuuming in high heels. However, American designers like McCardell retained a stalwart following, sometimes adapting the fit-and-flare Dior silhouette to suit their active clienteles’ preferences. The Smithsonian’s McCardell suit hails from this era.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/11/95/1195b648-2460-44e0-bb14-7c4830147211/u540acmeweb.jpg)

Smithsonian curator Nancy Davis points out that, characteristic of McCardell fashions, the suit on display is well worn. Women bought McCardell to wear repeatedly, for years, she says, and the designer was known to haunt the textiles mills, appropriating sturdy fabrics usually passed over for clothes. Still, her incorporation of hard-working fabrics like denim into playful, stylish showed that utility did not replace panache.

The Smithsonian’s neutral gray suit is washable and comprised of separate parts, each of which might be paired with other garments. McCardell often made garments lively, adding unusually colored accents like the mustardy stripes on the bodice beneath the jacket. Another McCardellism supplies an element of functional asymmetry—the skirt’s capacious pocket. Like all her clothes, this suit was intended to go with flats, never heels, which McCardell objected to personally. In its versatile workability, the suit describes historical continuity between the hard-working, denim-trouser-wearing World War II riveters, and the glass-ceiling-cracking businesswomen of the 1970s.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/0e/a0/0ea09114-b224-46df-bec3-c1a3554eea9e/rz002787web.jpg)

Since McCardell, working women have continued to seek out smart wardrobes, with stitching and style that endures for more than two spin cycles. In the 1970s, Diane Von Furtenberg built an empire on her savvy wrap dress, made to seamlessly transition from day to night, and not unlike McCardell’s own signature wrap-around.

In 1985, designer Donna Karan targeted businesswomen with the introduction of her take on a “capsule wardrobe,” based on seven versatile garments for work and play—very similar to the six-piece travel wardrobe McCardell designed in recognition of how automobiles and planes had increased women’s mobility.

Today, with inexpensive labor in developing countries, efficient technology, and super-cheap synthetics, the affordability alone of individual garments is much less a concern than it was for McCardell’s clientele. Instead, evidence of harsh labor conditions, like those that led to the collapse of the Rana Plaza building in Bangladesh in 2013, demonstrate the imperative for a reformed consumer mentality, one that prizes durability, not novelty. For the morally motivated as well as aesthetically attuned shoppers, Claire McCardell’s formative philosophy of well-made, easy to care for, and classically stylish fashion is more relevant now than ever before.

The new permanent exhibition “American Enterprise,” opens July 1 at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History in Washington, D.C. and traces the development of the United States from a small dependent agricultural nation to one of the world's largest economies.

American Enterprise: A History of Business in America

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/LeZottepicWEB.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/18/13/181374f7-6783-410d-a1b9-e3bab897403c/rz002048web.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/56/ab/56abc760-ece9-4928-a36f-7a48278d3259/rz002196web.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/fb/2a/fb2a42eb-6f0a-4f52-938f-2102cffaf5b4/rz002258web.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/LeZottepicWEB.jpg)