The 1968 Kerner Commission Got It Right, But Nobody Listened

Released 50 years ago, the infamous report found that poverty and institutional racism were driving inner-city violence

:focal(754x716:755x717)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/ce/40/ce406af0-3f3e-4dc2-abfb-977fc93a2e3c/nmaahc-2011_57_10_10.jpg)

Pent-up frustrations boiled over in many poor African-American neighborhoods during the mid- to late-1960s, setting off riots that rampaged out of control from block to block. Burning, battering and ransacking property, raging crowds created chaos in which some neighborhood residents and law enforcement operatives endured shockingly random injuries or deaths. Many Americans blamed the riots on outside agitators or young black men, who represented the largest and most visible group of rioters. But, in March 1968, the Kerner Commission turned those assumptions upside-down, declaring white racism—not black anger—turned the key that unlocked urban American turmoil.

Bad policing practices, a flawed justice system, unscrupulous consumer credit practices, poor or inadequate housing, high unemployment, voter suppression, and other culturally embedded forms of racial discrimination all converged to propel violent upheaval on the streets of African-American neighborhoods in American cities, north and south, east and west. And as black unrest arose, inadequately trained police officers and National Guard troops entered affected neighborhoods, often worsening the violence.

“White society,” the presidentially appointed panel reported, “is deeply implicated in the ghetto. White institutions created it, white institutions maintain it, and white society condones it.” The nation, the Kerner Commission warned, was so divided that the United States was poised to fracture into two radically unequal societies—one black, one white.

The riots represented a different kind of political activism, says William S. Pretzer, the National Museum of African American History and Culture’s senior curator. “Commonly sparked by repressive and violent police actions, urban uprisings were political acts of self-defense and racial liberation on a mass, public scale. Legislative successes at the federal level with the Civil Rights and Voting Rights Acts were not reflected in the daily lives of African-Americans facing police misconduct, economic inequality, segregated housing, and inferior educations.” Black racial violence was not unique in 1960s American culture, Pretzer says: White Southerners set a precedent by viciously attacking Freedom Riders and other civil rights protesters.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/fe/74/fe7488a2-1c4f-4bcb-b736-57d64089f4ec/nmaahc-2011_57_11_8.jpg)

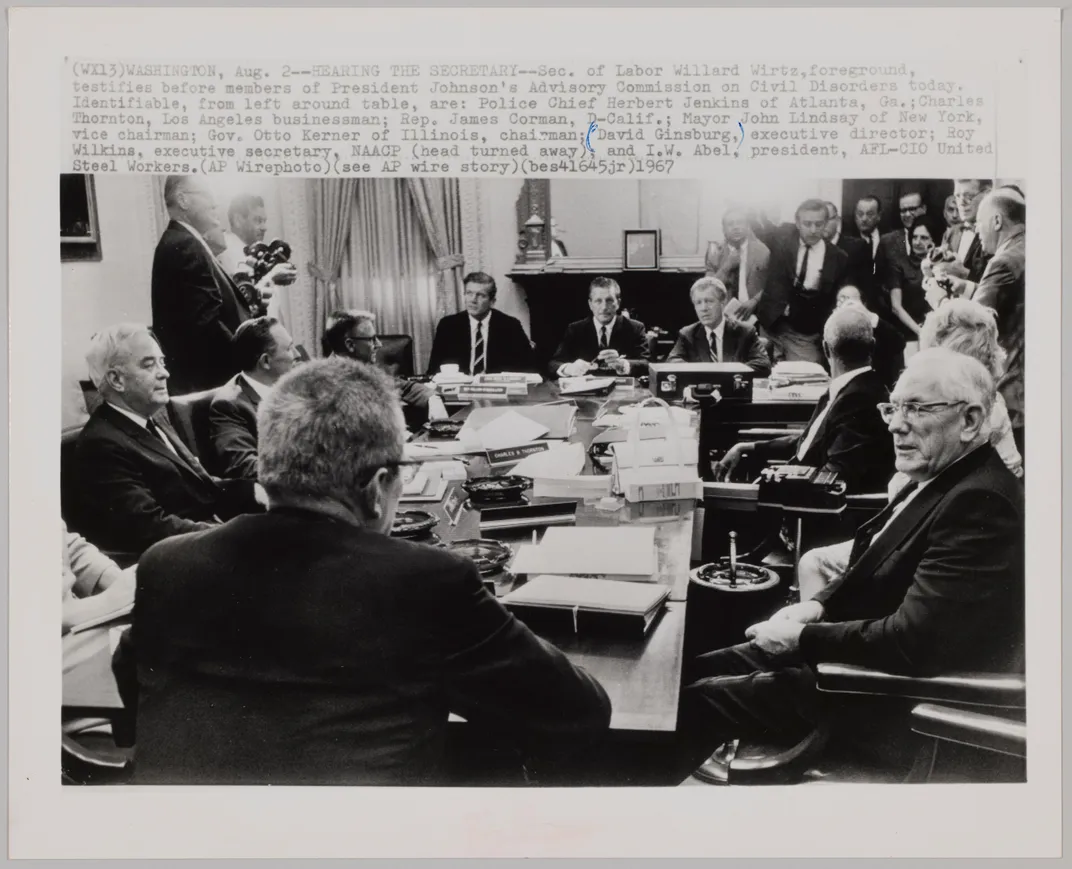

President Lyndon Johnson constituted the Kerner Commission to identify the genesis of the violent 1967 riots that killed 43 in Detroit and 26 in Newark, while causing fewer casualties in 23 other cities. The most recent investigation of rioting had been the McCone Commission, which explored the roots of the 1965 Watts riot and accused “riffraff” of spurring unrest. Relying on the work of social scientists and in-depth studies of the nation’s impoverished black urban areas, or ghettoes as they were often called, the Kerner Commission reached a quite different interpretation about the riots’ cause.

In moments of strife, the commission determined, fear drove violence through riot-torn neighborhoods. During the Detroit mayhem, “the city at this time was saturated with fear. The National Guardsmen were afraid, the citizens were afraid, and the police were afraid,” the report stated. The commission confirmed that nervous police and National Guardsmen sometimes fired their weapons recklessly after hearing gunshots. Intermittently, they targeted elusive or non-existent snipers, and as National Guardsmen sought the source of gunfire in one incident, they shot five innocent occupants of a station wagon, killing one of them. Contrary to some fear-driven beliefs in the white community, the overwhelming number of people killed in Detroit and Newark were African-American, and only about 10 percent of the dead were government employees.

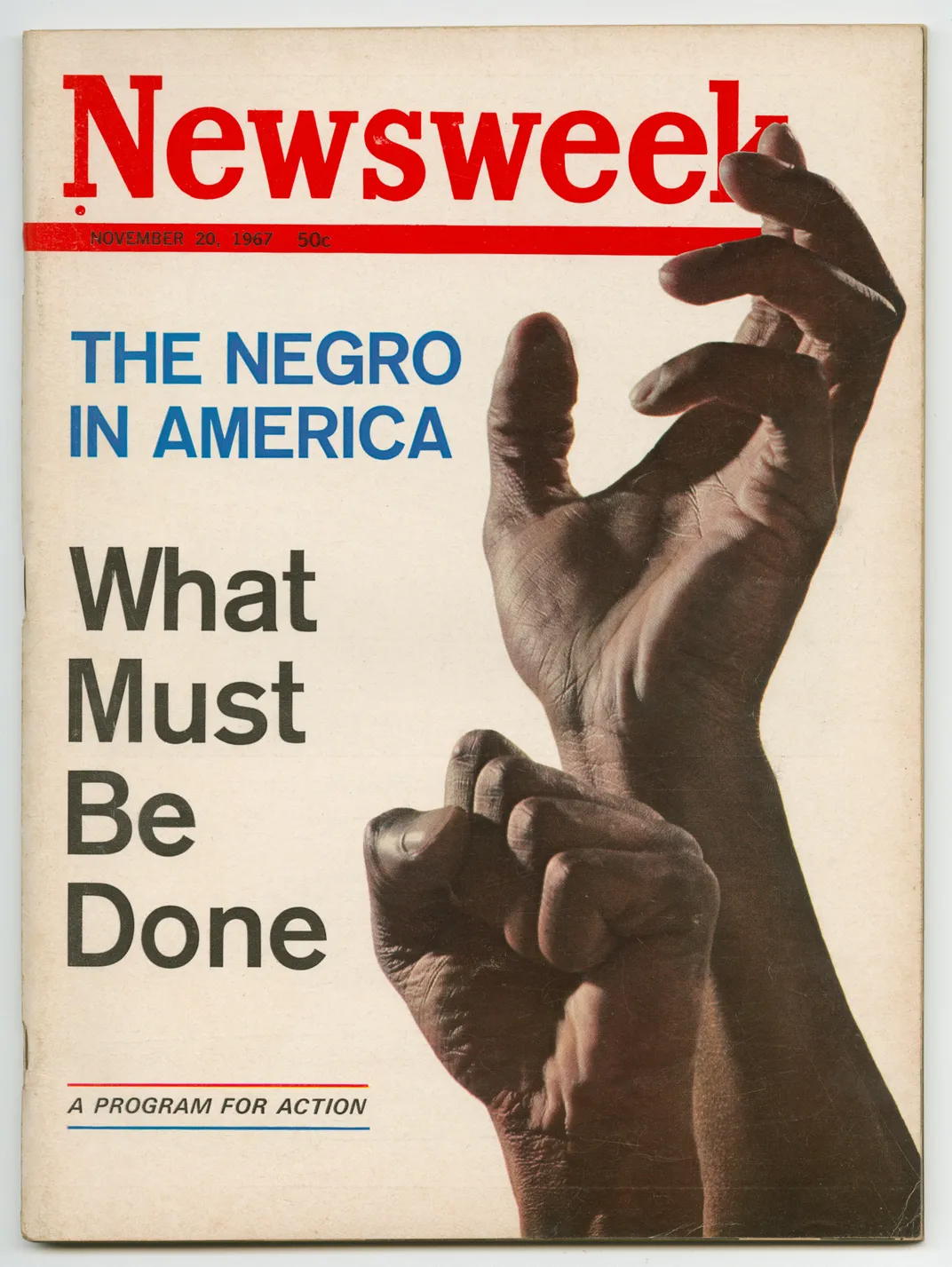

Finding the truth behind America’s race riots was a quest undertaken not just by the Kerner Commission: in late 1967 Newsweek produced a large special section reporting on the disturbances and offering possible solutions to racial inequality.

A copy of that issue resides in the collections of the National Museum of African American History and Culture. The magazine’s graphically powerful cover depicts two raised African-American hands. One forms the fist of black power; the other has slightly curled fingers. Perhaps, Pretzer says, that hand is reaching for the American dream—or on its way to closing another fist. “It was deliberately ambiguous,” he states. In addition, the cover bears this headline: “The Negro in America: What Must Be Done.” This seems to characterize African-Americans as nothing more than “a subject to be analyzed and decisions made about and for,” Pretzer believes.

The magazine interviewed a city planner who believed the answer lay in regimented integration. Under his plan, only a certain number of blacks would be re-located in each suburb so that whites would never feel threatened by their black neighbors. This would a create an integrated society, but would integration be right if it was achieved by once again limiting black options? As Pretzer suggests, the magazine’s exploration of radical change somehow still managed to treat African-Americans more like chess pieces than human beings, who might want to choose where they lived.

The magazine’s editor, Osborn Elliott, believed the package represented a move away from the objective reporting revered in this era and a rush toward a new type of advocacy journalism. Rather than merely reciting the numbers of people dead, buildings damaged, and store windows shattered, Newsweek sought to shape a future without these statistics. “The problem is urgent—as the exploding cities and the incendiary rhetoric make inescapably plain,” the magazine argued. Instead of whispering in its readers’ ears, Newsweek was screaming in their faces. The magazine published its issue about three months before the March final report of the Kerner Commission. This special project won a 1968 National Magazine Award from the American Society of Magazine Editors.

Newsweek’s findings did not go unnoticed, but the Kerner report created considerably more controversy. It rebutted a common critique contrasting the mass of primarily European immigrants who crowded into slums in the early 20th-century and African-Americans who moved from the rural South to urban centers in the middle of the century. Because most immigrants gradually moved up America’s social ladder, some have suggested that harder work would lead African-Americans out of poverty and into the middle class.

To the contrary, the commission argued that the crush of immigrants occurred when the boom of industrialization was creating unskilled jobs more quickly than they could be filled. African-Americans, on the other hand, arrived as industrialization wound down and the supply of unskilled jobs plummeted. Also, racial discrimination limited African-Americans’ ability to escape from poverty.

Moreover, the report deplored a common reaction to riots: arming police officers with more deadly weapons to use in heavily populated urban neighborhoods. Its primary recommendation was “a policy which combines ghetto enrichment with programs designed to encourage integration of substantial numbers of Negroes into the society outside the ghetto.”

Both the Kerner Commission and Newsweek proposed aggressive government spending to provide equal opportunities to African-Americans, and each won praise from African-American leaders and white liberals. Even so, the president of the United States was not a fan.

Johnson faced no pressure to respond to Newsweek, but it is rare for a president to offer no public endorsement of a report produced by his own hand-picked commission. Still, that’s what LBJ did.

The president had chosen moderate commission members because he believed they would support his programs, seek evidence of outside agitation, and avoid assigning guilt to the very people who make or break national politicians—the white middle class. The report blindsided him. He had suggested that Communist agitation fired up the riots and to his dismay, the report disagreed, asserting that the riots “were not caused by, nor were they the consequences of, any organized plan or ‘conspiracy.’” And the commission rejected another common allegation: the charge that irresponsible journalists inflamed ghetto neighborhoods.

Despite Johnson’s feelings, or perhaps because of them, the report became big news. “Johnson Unit Assails Whites in Negro Riots,” read a headline in the New York Times. Rushed into print by Bantam Books, the 708-page report became a best-seller, with 740,000 copies sold in a few weeks. The Times featured front-page articles about the report every day in the first week following its release. Within a few days, both CBS and NBC aired documentaries about the ties between race and poverty.

Backlash was immediate. Polls showed that 53 percent of white Americans condemned the claim that racism had caused the riots, while 58 percent of black Americans agreed with the findings. Even before the report, white support for civil rights was waning. In 1964, most Northern whites had backed Johnson’s civil rights initiatives, but just two years later, polls showed that most Northern whites believed Johnson was pushing too aggressively.

White response to the Kerner Commission helped to lay the foundation for the law-and-order campaign that elected Richard Nixon to the presidency later that year. Instead of considering the full weight of white prejudice, Americans endorsed rhetoric that called for arming police officers like soldiers and cracking down on crime in inner cities.

Both the Kerner Commission Report and the Newsweek package called for massive government spending.

When John F. Kennedy declared that an American would reach the moon by the end of the 1960s, even Republicans lined up behind him. In 1968, as they proposed an ambitious cure for racial inequality, Kerner Commission members probably heard echoes of JFK’s words: “We choose to go to the moon in this decade and do the other things, not because they are easy, but because they are hard.”

Indeed, the United States was prosperous enough to reach for the moon; nevertheless, Pretzer says, “The Johnson administration would not shift resources from the war in Vietnam to social reform, and Congress would not agree to tax increases. Further, state legislatures routinely blunted the local impact of federal actions.”

Ultimately, going to the moon was far easier than solving the nation’s racial issues. Politically, spending billions on space travel was more saleable than striving to correct racial inequality. Since the arrival of the first African slaves in North America early in the 17th-century, prejudice, often supported by law, has circumscribed the experiences of African-Americans.

Even when the first black president sat in the White House, lethal police attacks on young black men created racial turmoil. African-American poverty remains an issue today. In 1969, about one-third of blacks lived below the poverty line. By 2016, that number had dropped to 22 percent as a significant number of African-Americans moved into the middle class with a boost from 1960s legislation, but the percentage of blacks living in poverty is still more than twice as high as the percentage of whites. Blacks now have a louder voice in government, and yet, poverty and disenfranchisement remain. Notwithstanding the Kerner Commission’s optimism about potential change, there have been only scattered efforts over the last 50 years to end America’s racial divide or to address the racial component of poverty in the United States.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Alice_George_final_web_thumbnail.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Alice_George_final_web_thumbnail.png)