What Really Felled the Hindenburg?

On the anniversary of the conflagration, mysteries still remain

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/b6/11/b611d42c-35bb-4aec-a220-34c4a6ec7afe/nasm-si-98-15068.jpg)

“In the 20th century, there are events that cut across all our private lives,” says Tom Crouch, a curator at the Smithsonian’s National Air and Space Museum in Washington, D.C. “If you were alive on May 6, the day of the Hindenburg disaster, you remember where you were.”

As Crouch points out, there were newsreel film-cameras present and rolling, and WLS Radio’s Herb Morrison was broadcasting the events of the Hindenburg’s initial American landing live to tens of thousands more over the airwaves.

“Even today,” Crouch says, “anyone who hears the phrase: ‘Oh, the humanity,’ knows where it comes from.”

“But,” Crouch continues, “the age of the rigid airship had already passed, anyway.” The Hindenburg disaster, he implies, was merely punctuation.

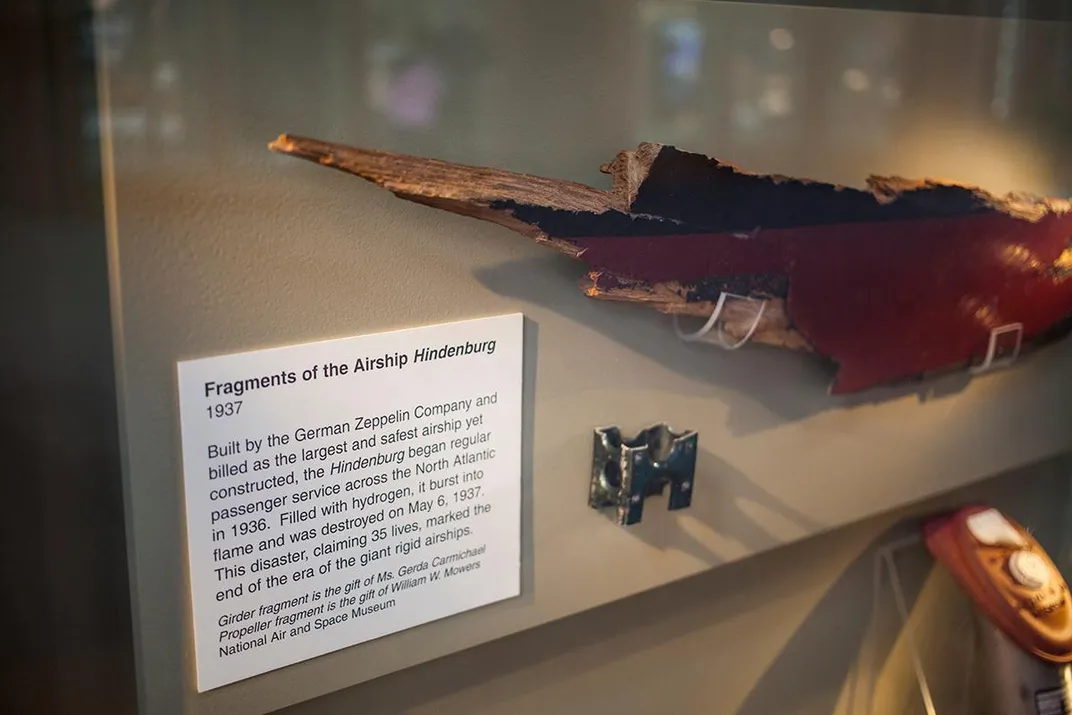

Still, being the repository for America’s history, the Smithsonian Institution has a strong representation of Hindenburg artifacts and ephemera. In the Institution’s iconic Castle on the National Mall, protected behind glass, is a chunk of a Hindenburg internal-support girder, plus a fragment from one of the airship's drive propellers.

In the basement of the Air and Space Museum, also on the Mall, is a scale model of the airship, used in the 1975 movie Hindenburg. And at the museum’s Udvar-Hazy Center in Virginia, near Dulles Airport, “we’ve got a ladder on exhibit,” says Crouch, “girder pieces on exhibit. . . the most striking thing on exhibit is a little demi-tasse cup and saucer, which are scorched from the fire.” And in the collections of the National Postal Museum is a scorched postcard that was carried in the mail aboard the airship and survived the flames.

And what a spectacularly disturbing fire it was. On May 6, 1937, the world’s largest dirigible airship went up in towering flames in New Jersey. While the Hindenburg had made passenger trips before, none would be like this one. On May 3, 1937, the hydrogen-floated Hindenburg departed from Frankfurt, Germany, bound for the first of ten round trip crossings to America. Not that the Hindenburg was new to Atlantic crossings, in 1936, it had transited the Atlantic, often to Brazil, 34 times.

It supplied this service because in that era aircraft crossings of the Atlantic were still impossible, the Hinderburg trips were intended to ferry passengers over the ocean, bringing them to Naval Air Station Lakehurst, in Manchester Township, New Jersey, just outside of New York City.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/fa/b5/fab5d4a2-e272-42bf-a4cc-c4f9f881e99f/nasmsi9815061web.jpg)

At Lakehurst, a mooring mast for airships awaited. Once tied-up, the Hindenburg’s 36 passengers could depart, where they would be picked up by representatives from American Airlines, who had contracted with the Hindenburg’s parent company for this trans-Atlantic shuttling. Then the passengers would be transported to Newark Airport to catch connecting continental airplane flights.

Hindenburg’s Atlantic crossing was relatively uneventful, other than some headwinds, that slowed U.S. landfall over Boston by about an hour. Then, once in the New York area, thunderstorms and bad weather thwarted the scheduled late-morning or early-afternoon rendez-vous at Lakehurst.

To avoid the storm, Hindenburg Capt. Max Pruss re-charted his course: over Manhattan and out into the Atantic, to wait until the storm blew through. The Hindenburg flew over New York City on its way out to sea, and was said to have created a sensation, with people running out of their houses, offices and stores to see the world’s largest airship overhead. Consider this: the Hindenburg was roughly the size of the RMS Titanic, but it flew overhead. And seeing that in the sky over New York City? Well, that would have been something to see. Pathé News, one of the big newsreel agencies of the day, even scrambled and sent out a biplane to get aerial footage of the huge Zepplin above the Empire State Building.

By 6:22 p.m., the storms had passed, and Captain Pruss ordered his ship to Lakehurst, almost a half-day late. By 7 p.m. on May 6, 1937, the Hindenburg was on final approach to Lakehurst.

The Naval Air Station was the selected choice, because its mooring mast had a winch. Large airships like the Hindenburg dropped its lines and cable to be run down through the mast and into the winch, which then would slowly pull the airship to the ground, allowing the passengers to depart. This procedure was known as a “flying moor.”

Then the winds began to shift, and Captain Pruss was having to make sharp left turns on approach and manage the Hindenburg’s propeller thrust in order to keep the airship’s nose directed at the mooring mast. Twice, as the airship began to drop in altitude from 650 feet to 295 feet, the airship had to make hard left turns into the wind. It was said to be a challenging landing.

Still, at 295 feet, the mooring lines were dropped to the ground as a light rain began to fall. Then, with the Hindenburg finally tied-into the ground winches, and as things were finally calming, at 7:25 p.m., the Hindenburg caught fire, the flames bursting from somewhere near the stern of the airship, though eyewitness accounts of exactly where the flames first emerged vary. Some say it was near the airship’s top steering/stabilizing fin. Others say the fire burst through the airship’s port side.

Unfortunately, while film of the flaming airship does exist, pictures—moving or otherwise—of the moment of ignition do not.

As the Hindenburg’s flaming tail began to drift toward the earth, the flames moved forward through the different hydrogen-holding cells toward her bow. The ship began falling precipitously. When the airship’s stern hit the earth, the fire burst through the airship’s nose-cone. The entire disaster was over in less than 40 seconds.

Remarkably, of the 97 people aboard (36 passengers and 61 crew), only 35 were killed (13 passengers and 22 crew), plus one person on the ground: for a total of 36 fatalities out of a possible 97 people.

While the May 6, 1937 disaster will be forever remembered, the age of the airship was over. There would be boards of inquiry and hearings and a U.S. Department of Commerce report to try and assess what had happened, without much success. But, Crouch says, the underlying fact is, airship production ended shortly after with the disaster.

After the fire, Deutsche Zepplin-Reederei made one last airship, as it was already on order. Then World War II, its speedy fighter aircraft easily able to feed on the slow-moving airships, ended not only the company, but the industry.

After the disaster, there was one other airship still flying, Crouch says. “It was the Graf Zepplin 2, the Hindenburg's sister ship. At the end, they flew it along the British coast, to test British Radar systems before the war. But they took it down in 1937.”

As for the certain cause of the Hindenburg disaster, Crouch says, we will likely never know. “People thought it was sabotage for a long time,” he says, “but that theory has been pretty much discounted.”

Instead, Crouch says, the reigning hypothesis now is a combination of static electricity built up as the airship flew, and an unusual type of “dope” used to cover the canvas of the hydrogen-storage areas: paint that rendered the canvas gas impervious but also appears to have been highly flammable. The “incendiary paint” was a mix of iron oxide and aluminum-impregnated cellulose, which are reactive together even after drying.

“My friend, Addison Bain, has a theory that the canvas skin was doped,” Crouch says, “and it was flammable…. He wrote a book about it. And as a former rocket scientist at NASA, he’s familiar with how propellants work.” Basically, Bain’s theory is that the Hindenburg was painted with rocket fuel.

“It was rainy, misty, dismal day,” Crouch says, “and a large, ungrounded ship moving through the sky builds up quite a static charge. That’s why, before landing, they always dropped the ropes to the ground, made sure they touched the ground first, to dissipate the static.”

Then, Crouch says, when adding the static charge to the “flammable dope” skin, and with the vast stores of hydrogen that lay waiting just beneath, a good possibility exists that that’s what caused the Hindenburg to catch fire and burn its way into modern memory—and history.

“Another theory,” Crouch says, “is that the two, hard left turns near landing snapped a steering cable at the back of the airship, and the cable was flailing around, perhaps creating sparks.”

This loose and flapping cable might have punctured one of the sealed hydrogen cells inside the airframe, releasing hydrogen into the air inside the Zepplin’s outer skin. This coupled with static electricity and the flammable skin might have been the perfect collision of circumstances that set the Hindenburg disaster into motion.

According the U.S. Department of Commerce report on the accident, a ground-crew eyewitness named R.H. Ward, spotted “a notable fluttering” in the airship’s skin about two-thirds back down the airframe as they began the landing process. As did R.W. Antrim, who was atop the mooring mast. This may have been a sign that hydrogen was leaking from one of the cells.

Still, in the end, even the U.S. Department of Commerce and the U.S. Navy couldn’t come to any solid conclusion in their report, either, instead simply stating the obvious: the firey disaster was a result of the “mixture of free hydrogen and air.”

Four score years have now passed, and everyone knows the story—and has seen the footage—of the burning airship, and yet the mystery Hindenburg disaster lives on, likely never to be definitively solved.

It's your turn to Ask Smithsonian.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Don4x5.tif)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Don4x5.tif)