Meet the Master Muralist Who Inspired Today’s Generation of Paleoartists

The treasured Jay Matternes murals of lost Mesozoic worlds are featured in a new Smithsonian book

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/60/fd/60fdf000-0c68-4e8c-805f-844b60826e77/matternes_20150317_0019.jpg)

When the new fossil hall at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History opens June 8, after a five-year, $110 million renovation, the spotlight will naturally be on the spectacular assemblages of specimens including the Tyrannosaurus rex skeleton so popular it’s called “The Nation’s T-Rex.”

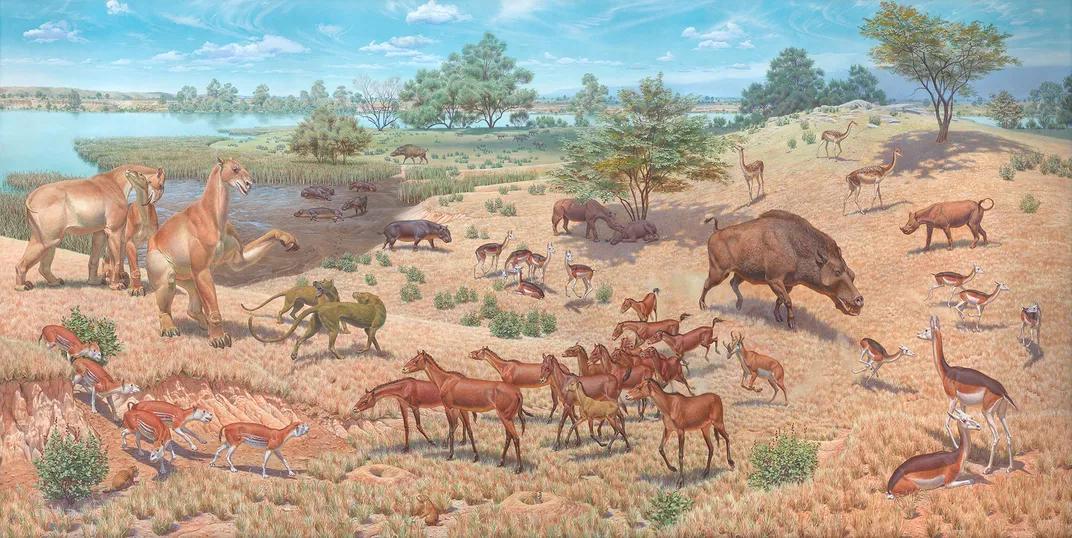

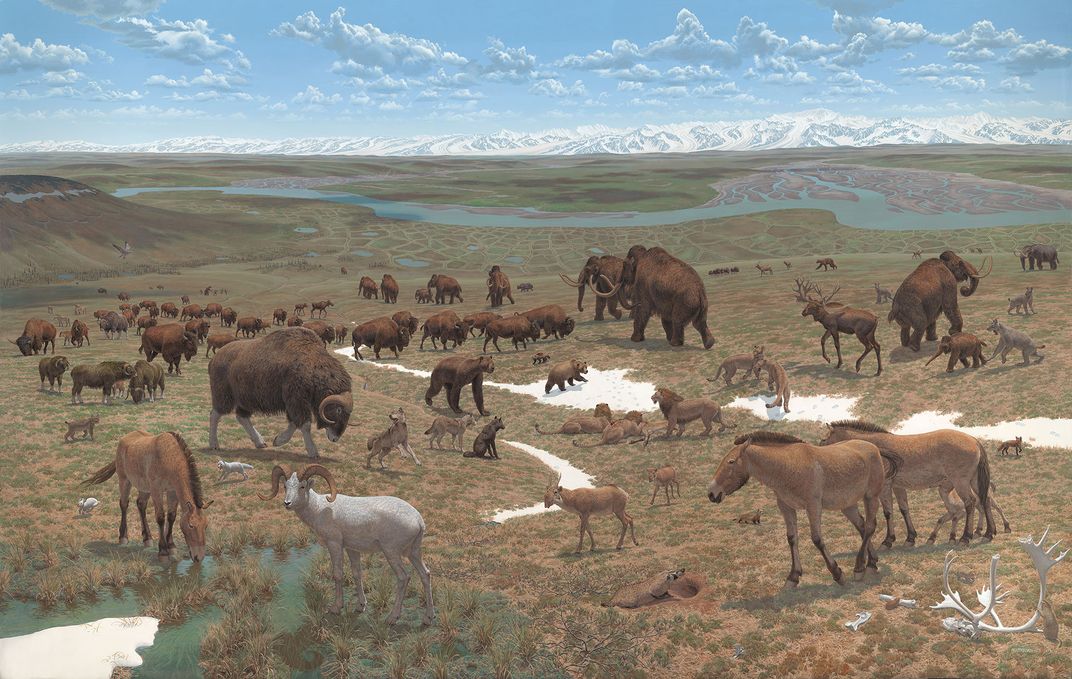

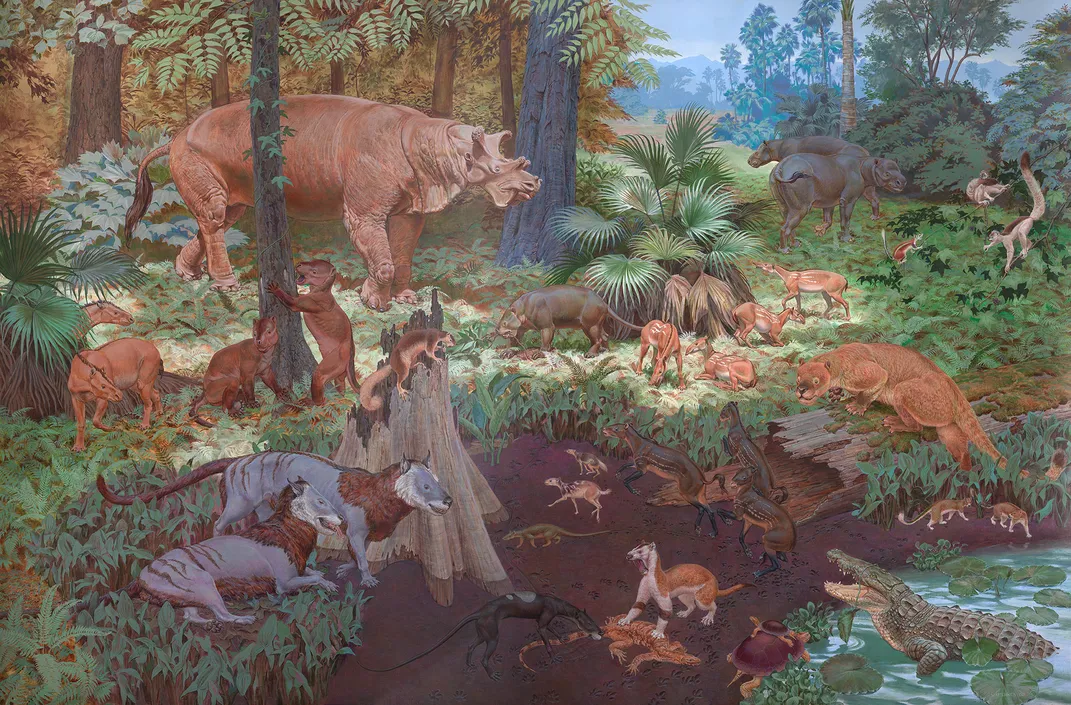

But behind them will be an array of intricate and spectacularly-detailed murals from a team of top international paleoartists, many of whom were inspired by the memorable works by the renowned American painter and naturalist Jay Matternes and that have stood in the same hall for decades.

Two of the six wall-sized murals that Matternes completed for the hall more than four decades ago will be represented by life-size digital reproductions that preserve the kind of fly-on-a-mammoth detail that sparked the artists that followed in his footsteps.

The originals, painted between 1960 and 1975 and seen by millions over the generations, were carefully cut from the walls when the hall was closed for renovation in 2014. They were preserved in the Smithsonian's archives because they had become too fragile to mount again, says Siobhan Starrs, exhibition developer for the extensive “Deep Time” exhibition.

Still, they provided inspiration for the artists who did their own murals and artwork, as well as those who rearticulated the fossil skeletons. “The pose of the sloth is the same as the pose of the sloth in the mural,” says Starrs pointing out the digitized reproduction of a Matternes work on the wall behind the sloth fossil.

“He’s very influential for me and extremely inspiring,” says Julius Csotonyi, 45, the in-demand paleoartist from Vancouver who completed 59 separate works for the new hall. “Matternes does such an amazing job of realism in his artwork. What he does is make a prehistoric world and prehistoric creatures and not make them look like monsters, as some artwork might portray, but as real animals. His command of lighting is spectacular, the amount of detail that he puts into these pieces is just astounding.”

Visions of Lost Worlds: The Paleoart of Jay Matternes

For half a century, the artwork of Jay Matternes adorned the fossil halls of the National Museum of Natural History. These treasured murals documenting mammal evolution over the past 56 million years and dioramas showing dinosaurs from the Mesozoic Era are significant works of one of the most influential paleoartists in history.

Matternes’ work is even known as far as Siberia, where Andrey Atuchin, another paleoartist hired for the project, works.

“I had always thought of myself as an artist/naturalist,” says the now 86-year-old Matternes, from his home in Fairfax, Virginia. Back when he was on ladders and scaffolds doing the original murals, there wasn’t such a term as “paleoart.” But the tenets of the practice are the same, he says. “In order to interpret the past, you have to have a pretty good working knowledge of conditions in the present.”

He would dissect zoo animals and cadavers to understand the animal's physiology, “working from the inside out,” according to Richard Milner, an associate in anthropology at the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. He would sketch skeletons and add muscle, skin and fur to bring a full picture of what the prehistoric must have looked like.

Animals in past eons, Matternes says, “had the same problems and the same adaptations to the environment as is true of the animals today.”

Many of his preliminary sketches and drawings appear in the upcoming Visions of Lost Worlds: The Paleoart of Jay Matternes, from Smithsonian Books; “so much of which is beautiful in its own right,” says Matthew T. Carrano, the National Museum of Natural History’s dinosaur curator and the book’s co-author with museum director Kirk Johnson.

“Especially where he would do something like he would draw the skeleton, and then he’d draw multiple layers of muscles, and then he would toy with different textures of fur,” Carrano says. “You almost feel like it’s a shame you only got to see that last version.”

Carrano is one of the many whose link to dinosaurs came directly from Matternes—specifically his illustrations in a popular 1972 National Geographic book. “That was the first dinosaur book I’d ever seen. And I remember the day I saw that,” he says. “I found it totally fascinating. I could not get it out of my head. So I got to be one of these obsessed dinosaur kids, and it really all came from seeing his pictures.”

Working on the original murals, Matternes says he had to sometimes work behind a temporary wall when the museum was open. “I could be isolated from the public by a wall as I worked behind a barricade, but I could hear the comments of the public as they passed on the other side of that wall, which was very interesting.”

He was on a tight deadline, even then. “My thing is I’d arrive at the museum about mid-morning, and then I would work all day, and then I’d take a very brief dinner break, and come back and work until they kicked me out at 10 o’clock,” Matternes says. “I would do that on a daily basis.”

The work captivated visitors for generations and subsequently provided a basis for the artists hired for additional murals and artwork in the permanent “Deep Time” exhibition, from Csotonyi and fine artist and designer Alexandra Lefort in Vancouver and Atuchin in Russia to Davide Bonadonna of Italy, Dwayne Harty, a Canadian wildlife artist working in Jackson Hole, Wyoming, and Michael Novak, an artist and fabricator in Sterling, Virginia, who along with Lefort created the 24-foot-metal trees that frame the entrance way of the 31,000-square-foot fossil hall as it traces a timeline that recedes through 3.7 billion years of life on Earth.

“They’re massive things,” Novak says. Working with scientists and exhibit creators, “We were tasked with creating implied three-dimensional view of these ancient trees in groupings, each tree different from the other, representing a nice blend of the science and a nice aesthetically-pleasing presentation.”

To do that, there had to be a continuity between the various artists. Because Csotonyi had done so much work, and gotten it in early, it set the tone—and the palette—for the rest, Novak says. “It’s really important when you walk into the gallery everything unifies. You get that sense when you’re walking though that front door.”

The artists know that their art work is not just the colorful background for the dinosaur bones, but the context and setting that further brings a prehistoric time to life.

“The bones allow us to see the overall shape of the animal—in 3D no less,” Csotonyi says. “But one of the purposes of the murals is trying to show what this would look like in an ecological content, putting the animal or the plant, in the proper ecological context, to see what else would have been alive at the time.”

He likened the circular edges to many of the new murals as port holes into the Mesozoic or Paleozoic periods, allowing viewers “to look through a telescope through deep time to see what its vistas were like.”

Atuchin compares it to “a virtual bridge between science, fossils and ordinary people. Seeing a skeleton with a visual reconstruction of it, one is more likely to recognize it was a real living creature.”

Inspired by “Jurassic Park,” Atuchin, 38, says he began studying fossils and biology as he drew more scientifically-based dinosaur drawings. “I started to work using traditional techniques: pencils, gouache, watercolors. Some time ago, I shifted to computer graphics, digital painting. It gives, as for me, more possibilities and freedom.” Like most paleoartists, he can also work from anywhere—“from Antarctica or even the Moon”—thanks to the internet.

That was never available to Matternes, who put brush to canvas directly at the museums he enhanced with his art. “No, I am of the old school,” he says. “As a matter of fact, I’m still struggling with learning about computers.” But, he adds, “If I were starting my career today, I would certainly go with digital art. That’s the wave of the future.”

Atuchin, who has only been to the U.S. once, for a visit to the Denver Museum of Nature and Science, where he participated in a paleontological excavation in Utah, has never had a chance to visit the Smithsonian. Political red tape prevents his appearance at the opening of the “Deep Time” exhibit.

For his part, Matternes will be digging out his old tux for the opening and Csotonyi for one will be looking forward to seeing him, as well as the art.

“He’s one of my artistic heroes,” Csotonyi says. “Just spectacular stuff. I’m very happy they’re able to keep some of his artwork displayed in the exhibition, because I really think people need to see it. It’s just fantastic.”

The Hall of Fossils—Deep Time, opens June 8 at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History in Washington, D.C.

Editor’s Note, June 5, 2019: A previous version of this article did not include the work of artist Alexandra Lefort. We regret the omission.

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/RogerCatlin_thumbnail.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/RogerCatlin_thumbnail.png)