The world watched and waited on December 4, 1993, as Space Shuttle astronauts corralled the Hubble Space Telescope and began to fix its blurry optics. For the next five days, crewmembers conducted long space walks to repair a flaw in the mirror. Back on Earth, millions of people watched late into the night on television to see if the astronauts could do it.

Of course, they did repair it. For three decades now, Hubble has sent back a bounty of incredible interstellar images, providing an unparalleled look deep into the cosmos and adding critical knowledge to our understanding of space.

As the world watches and waits once again with the pending upcoming launch of the new James Webb Space Telescope on December 25, recalling the long history of its predecessor—which will continue to operate for the foreseeable future—puts a potent perspective on how far we’ve come since Hubble was launched in 1990 and repaired in 1993. The array of photos, including deep field—a sort-of time-lapse shot showing all the stars—gives us a sense of all that what we had been missing before.

“I love the Hubble Deep Fields image,” says Samantha Thompson, curator of science and technology at Smithsonian’s National Air and Space Museum. “It’s not necessarily the most beautiful to look at, but what it shows us of space is like, ‘Whoa!’ Look at the photo. It shows how much we have accomplished with Hubble.”

Many of the more than one million images taken by Hubble were works of art, offering spectacular views of breathtaking beauty of stars and galaxies thousands of light years away. These natural masterpieces displayed distant nebulae, space clouds and other celestial wonders in such fine detail that astronomists began to better comprehend how cosmic forces shape space.

“Hubble has helped us understand how the universe is accelerating but it’s also slowing down,” Thompson says. “We’ve learned more about dark matter and have detected black holes thanks to Hubble. By looking at these images, we can see things we’ve never seen before and gain insight into our relationship with other galaxies.”

None of this would have been possible if Hubble had not been designed the way it was. From the beginning, NASA wanted to create a space telescope that could be updated and repaired so it would continue to serve science for decades.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/5b/8a/5b8a0586-7017-4f8d-8765-a14d5fbc1e21/hubble_ngc2024_flame1_wfc3_ir_display.jpeg)

That flexibility allowed members of Space Shuttle mission STS-61 to fix Hubble after scientists figured out why the images initially were so blurry: an imperfection in the massive mirror inside the 45-foot space telescope. Astronauts were able to make repairs by installing new hardware to correct the defect. Since 1993, Space Shuttle crews have made four more servicing missions to this eyepiece on the stars.

“The stories of astronauts working on the telescope add a different element to astronomy that we don’t always get," says Thompson. "We built Hubble to help us better understand our place in the universe.”

The space telescope was first conceived in the 1940s—before humans even had the ability to escape earth’s gravitational pull. Work began in earnest in the 1970s when Congress provided initial funding. In 1975, contractor Lockheed Missile and Space Co. built a full-scale mockup to conduct feasibility studies.

Later named the Hubble Space Telescope Structural Dynamic Test Vehicle (SDTV), that artifact is on display in the Space Race exhibition at the National Air and Space Museum in Washington, D.C. It was donated by Lockheed to the Smithsonian in 1987 and then restored to its original configuration. In 1996, the SDTV was upgraded to simulate the actual space telescope in orbit around the planet.

The test vehicle was instrumental in enabling NASA and Lockheed to build Hubble. They used the SDTV to determine how the space telescope would work and to check stressors before launching the real deal into space. It also served as a frame for building cable and wiring harnesses and was used for simulations in developing maintenance and repair protocol for the space telescope.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/b7/d4/b7d4b344-b070-47cf-89c6-aaf3351f7bc1/nasm2012-00176_hubble.jpg)

“The test vehicle is the exact same size as the flown Hubble,” Thompson says. “It was built to see if the space telescope would withstand the vibration of a space launch and handle the coldness of space. It was the practice version of Hubble.”

Though the SDTV never left Earth, it was integral to the development of the space telescope now orbiting the planet. If not for this artifact, the real Hubble might have never gotten off the ground to take the stunning snapshots of space that have furthered our understanding of science and our place in the vast cosmos, including the age of our universe—13.8 billion years—two new moons around Pluto and how nearly every major galaxy is anchored by a black hole.

“Hubble captured the public’s attention and continues to be a source of excitement when it comes to astronomy,” Thompson says. “I love it for that. I think it’s hard to get people to understand what is happening with the universe, but when you can see a picture, we get a sense of where we are and how much else is out there.”

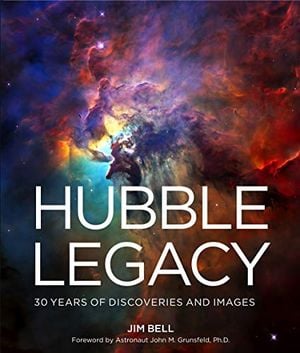

Hubble Legacy: 30 Years of Discoveries and Images

If there is a single legacy of Hubble as it turns 30 years old and nears the end of its useful life, it is this: It has done more to chronicle the origin and evolution of the known universe than any other instrument ever created. This is the definitive book on the Hubble Space Telescope, written by noted astronomer Jim Bell.

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

:focal(640x427:641x428)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/c2/bd/c2bd7772-08f4-45c9-87c2-b48c4d1281b2/s31-03-009.jpeg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/dave.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/dave.png)