A Look Into the Innovative Mind of One of the World’s Most Inventive Architects

A new show at the Cooper Hewitt reveals the process behind designer Thomas Heatherwick’s projects

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/cb/e4/cbe4660b-2248-4f96-83cb-101bf2dfcdb3/thisone.jpg)

Shortly before his first New York show opened at Cooper Hewitt, the Smithsonian Design Museum, Thomas Heatherwick realized he had a problem.

“They told us the bus wouldn’t fit!” he exclaims. But the bus in question (really just the rear section of a bus) was one of the key items in the show, an example of Heatherwick Studio’s design diversity—from buses to handbags—and ubiquity.

In 2010 his studio was asked to redesign London’s iconic double-decker bus; today, thousands of these buses putter and roar down the city’s streets. He decided to bring the bus to New York from London anyway. It ended up just barely fitting through the front doors. “It’s jammed in,” says Heatherwick of the bus’ placement between two staircases, “but jammed in more interesting than not here.”

Even if the bus hadn’t fit, it’s hard to imagine Heatherwick not finding a solution. Variously described by others as a designer, inventor or artist, he sees himself as a problem solver.

“Once you define the problem,” he explains. “That gives you a basis for working.”

The show at Cooper Hewitt, Provocations: The Architecture and Design of Heatherwick Studio, reflects this approach. Everything is labeled with the problem it was designed to solve. The plaque next to the bus poses practical questions: “Can a London bus be better and use 40% less fuel?”

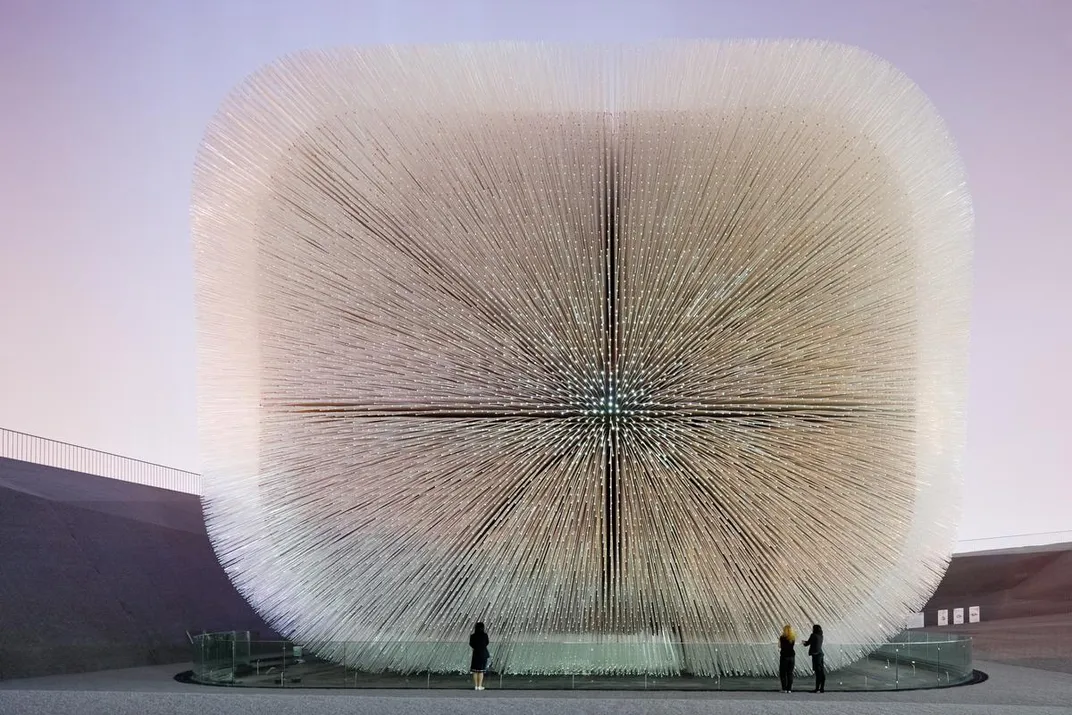

A few questions displayed are simply functional. For example, “Can a drawbridge open without breaking?” accompanies a working model of a bridge (the real thing was built at London’s Paddington Basin in 2004) that curls up on itself like a pillbug. Others are philosophically complex. “How can a building represent a nation?” reads a plaque next to a model of the Seed Cathedral, a dandelion puff of a building designed for the 2010 World Expo in Shanghai. Sixty-six thousand acrylic rods shimmer on the outside while, inside, the rods’ tips display 250,000 seeds from London’s Kew Gardens.

This project, according to curator Brooke Hodge, is what put Heatherwick on the map.

“When we started to plan this show in 2009, I’d tell people about it and nobody knew who he was,” she says. “He doesn’t give lectures, he doesn’t promote. But after Shanghai I’d say, ‘He did the Seed Cathedral,’ and architects would go, ‘Ohhhhhhhh.’”

“Then, of course, he did the 2012 Olympic cauldron,” she adds. “And the general public began to know who he was.”

Cauldron and bus, buildings and bridges, join handbags, furniture and landscape design to create a body of work that’s difficult to sum up “Heatherwick’s difficult to categorize, [and that’s] part of what makes his work exciting to me,” says Beth Altringer, a professor at Harvard’s Graduate School of Design. “His diverse body of work leaves us questioning whether and how it makes sense to separate specialist forms of design.”

Heatherwick explains that his broad range of projects is partly a function of his upbringing. “I grew up around craftspeople,” he explains. “My mother was a jeweler, so I spent quite a bit of time with people who were making things, whether it was glass blowing or stone carving.” But his “passion for public projects” comes, he says, from his maternal grandfather, Spanish Civil War veteran Miles Tomalin, who “was fascinated with engineering and industry.” Among Tomalin’s many projects was a book called Coal Mines and Miners and a campaign to prove fellow Welshman Richard Trevithick was the rightful inventor of the steam locomotive.

For his part, Heatherwick “grew up being interested in ideas,” he says. “I liked to tinker. But in Britain ‘inventing’ was always connected with the mad scientist character, like Caractacus Potts from Chitty Chitty Bang Bang.” It’s an association he’s mentioned in several interviews, and, in a sweater vest and baggy patterned trousers, eyes enthusiastically wide under tousled curls, he does look the part of a 19th century inventor. It’s easy to picture him riding his recumbent bike (a Victorian invention) to the Royal College of Art, where he got his masters in art in design products, a program that encompasses everything from textiles to appliances to cars. While at RCA, he showed his design for a Victorian-inspired gazebo to visiting lecturer Sir Terence Conran, the design entrepreneur who founded the Habitat home store. Conran was so impressed that he invited Heatherwick to build the gazebo on his estate.

Soon after graduation, with Conran as a mentor, he founded Heatherwick Studio. What was then a small undertaking—just Heatherwick and fellow RCA graduate Jonathan Thomas—is, 20 years later, a bustling warren of nearly 200 designers, architects and “makers.” This diverse staff is the other reason Heatherwick’s range of projects is so broad: the team is highly collaborative, and because their skills are so varied their projects can be too. “It’s more stimulating to always be doing something different,” he explains. “We never want the illusion of solid ground.”

Though none of their projects is the same as the last, the studio has its own form of consistency. “Our process is the only thing we’ve done over and over, really refined it, and it works,” Heatherwick says.

The process has two main components: a team and a problem. Each incoming project is assigned a project leader and a small team. Together, they identify the problem to be solved and brainstorm ways to solve it. Heatherwick goes from project to project, depending on where he’s needed. “It’s a sort of pushing and pulling in every direction,” he explains. “I feel we’re not experts at any one thing, but we are experts at not being experts.”

It’s this outsider approach that makes Heatherwick’s work so innovative, according to Clifford Pearson, an architecture historian and editor at the Architectural Record: “He has this childlike quality, in a good way, of looking at things and asking why, why, why—questions that go to the heart of the problem.”

“There’s a freshness and an energy to his work,” continues Pearson. “That said, we haven’t really seen him do many big projects from scratch [Heatherwick has done several large remodels]. It will be interesting to see if he can translate this inventiveness to a larger scale.”

Big projects are on the way. In November 2014, Heatherwick Studio’s commissioned designs for Pier 55, a floating park and performance space on Manhattan’s west side, were made public. Four months later, Google announced that Heatherwick Studio, in collaboration with the Bjarke Ingels Group, is redesigning their Mountain View, Californian, campus.

When asked it if it’s difficult to maintain his process while collaborating with another firm, Heatherwick shakes his head. “I find the external collaborations are really good for the mix of things,” he says. “We’re collaborating willy-nilly at the moment. It’s like that saying: ‘A problem shared is a problem halved.’”

"Provocations: The Architecture and Design of Heatherwick Studio" is on view at the Cooper-Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum in New York City through January 3, 2016.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/marymann.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/a3/9a/a39a7dbf-f04e-4e20-84d0-9a60262ed57a/198_02_hr_eastbeachcafe_credit_andystagg.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/11/27/1127b66d-562f-46bf-9747-34752b871217/416_02_hr_extrusions_credit_peter_mallet.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/59/21/5921bac2-40b8-40fa-b7c4-60f7a5b1bbfa/816__01_hr_gardenbridge_credit_arup.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/30/9e/309ec710-569c-4056-838c-6ea16da79c61/megan_radke_in_a_spun_chair.jpg)