A Natural Hair Movement Takes Root

From her salon in Maryland, Camille Reed sees more black women embracing natural hair

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/20130607093044Salon_Thumb2.jpg)

From her salon in Silver Spring, Maryland, Camille Reed spreads the message of natural hair to her clients. And it seems to be catching on. The products once advertised to black women in the pages of Ebony and elsewhere are on the decline. Between 2009 and 2011, sales of chemical straighteners dipped 12.4 percent, according to Danielle Douglas reporting for the Washington Post with data from market research firm Mintel. In 2011, the number of black women who said they no longer relaxed their hair hit 36 percent, a 10 percent bump from 2010.

Reed, a participant in a discussion about health and identity at the African Art Museum tonight, says she’s seen the changes too. She opened Noire Salon 13 years ago because she wanted, “young women to understand that they can be beautiful without the wigs, without the weaves, without the extensions.” Her second-floor shop sits right outside D.C., a hot bed of hair whose salons reported the highest sales per business in the country in 2007, according to census data. Offering a range of services from coloring to cutting to dreadlock maintenance and styling, Reed says she tries to use as few chemicals as possible and instead work with a person’s natural hair to create a healthy, stylish look. ”Girls are not buying the chemicals as much,” she says, “They’re still buying the weaves here and there because people like options but they’re not buying the harsh chemicals.”

The history of African-American hair care is a complicated one. Early distinctions existed during slavery when, “field slaves often hid their hair, whereas house slaves had to wear wigs similar to their slave owners, who also adorned wigs during this period,” according to feminist studies scholar Cheryl Thompson.

The history also includes the country’s first female, self-made millionaire, Madam C. J. Walker, a black woman who made her fortune selling hair care products to other black women in the early 1900s. Begun as a way to help women suffering from baldness regrow hair, her company later promoted hot comb straightening–which can burn the skin and hair and even cause hair loss–creating a tangled legacy for the brand and speaking to the fraught territory of marketing beauty.

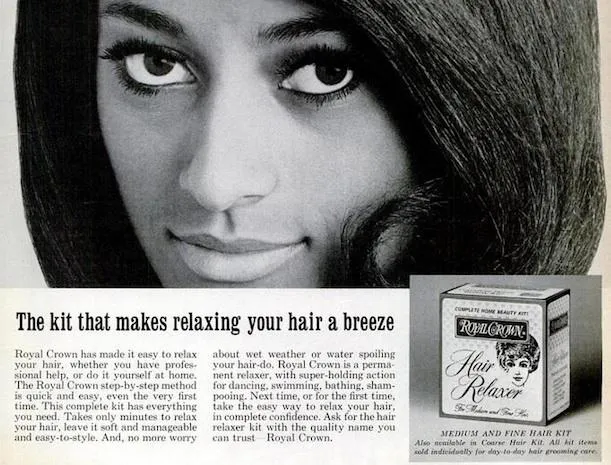

Eventually the business of straightening won out. In the August 1967 issue of Ebony alongside a profile of a 25-year-old Jesse L. Jackson, a look at the birth of Black Power and an article on gangs in Chicago, there is a mix of advertisements promising better skin and hair. “Lighter, Brighter Skin Is Irresistible,” reads one for bleaching cream. Another single-page spread offers a 100 percent human hair wig for $19.99 from Frederick’s of Hollywood. Chemical relaxers were sold alongside titles like James Baldwin’s “The First Next Time.” As clear as it was that messages of inherent inequality were false, there pervaded an image of beauty, supported by an industry dependent on its propagation, that placed fair skin and straight hair on a pedestal.

When activists like Angela Davis popularized the Afro, natural hair gained visibility but also a reputation for being confrontational. As recently as 2007, black women were told by fashion editors that the office was no place for “political” hairstyles like Afros, according to Thompson.

Reed says the pressure is internal as well, “It’s really more of our older generations, our grandmothers and our great-grandmothers who were saying, don’t you do anything to rock the boat, you look like everybody else so that you can maintain your life.”

Reed’s own personal hair history is a deeply inter-generational story. Her grandmother was a hair stylist at a salon in Cleveland, Ohio, where her mission, says Reed, was to transform women and give them confidence. “My grandmother was about the hair looking good, looking right,” says Reed. In the context of racism, if hair was a woman’s crowning glory, it was also a shield.

Meanwhile, she says her mother taught her about cornrowing and her aunt, who was one of the first to introduce the track weave, showed her how weaves could be used to supplement damaged hair and not necessarily to disguise a woman’s natural hair.

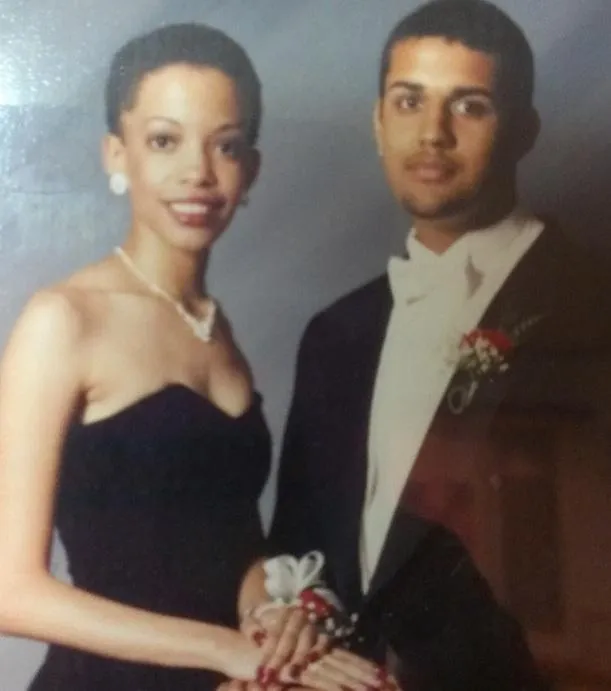

In high school, Reed says, “I was the girl who had her hair done every two weeks like clockwork because that’s how I was raised, to keep your hair done.” Then, three weeks before her senior prom she says, “I realized, this relaxer life is not for me. All of this stuff I have to do with my hair, this is not who I am, this does not represent me…I cut off all of my relaxed hair, left me with about an inch, inch and a half of hair.”

In college she decided she wanted even less maintenance and began to lock her hair. To her surprise, her grandmother actually liked the change. “And we were all just floored because this is the woman we knew who didn’t like anything to do with natural hair.”

Now Reed has children of her own, a son and daughter, whom she is teaching about beauty and hair care. “I purposefully let my son’s hair grow out about an inch to two inches before I cut it because I want him to feel comfortable with it low and shaven and faded–and I do all that–as well as feel comfortable with it longer, a little bit curlier so he knows, whichever you way you look, mommy and daddy still love you.”

For her clients, the message isn’t too different.

Camille Reed will be participating in a panel discussion “Health, Hair and Heritage,” hosted by the African Art Museum and the Sanaa Circle the evening of Friday, June 7 in the Ripley Center.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Leah-Binkovitz-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Leah-Binkovitz-240.jpg)