Alexander Gardner Saw Himself as an Artist, Crafting the Image of War in All Its Brutality

The National Portrait Gallery’s new show on the Civil War photographer rediscovers the full significance of Gardner’s career

Before Alexander Gardner made the most memorable photographs of the American Civil War, he had a hard time making up his mind. As a young man in Scotland, he had been an apprentice jeweler. Then he became editor and publisher of a Glasgow newspaper. In 1856, when he came to America, he was planning to start a socialist cooperative in unsettled Iowa. But then, in New York, he found his life's work.

Before leaving home, he had seen and admired photographs by Mathew Brady, who was already famous and prosperous as a portraitist of American presidents and statesmen. It was Brady that likely paid Gardner's passage to New York and soon after arriving, he went to visit the famous photographer's studio and decided to stay.

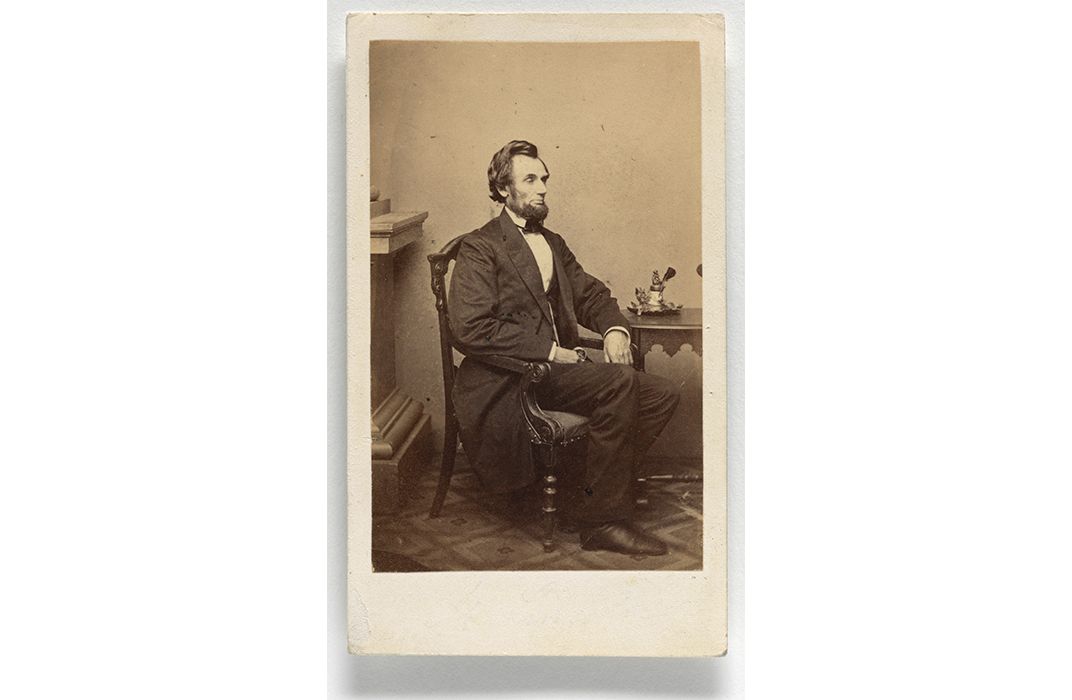

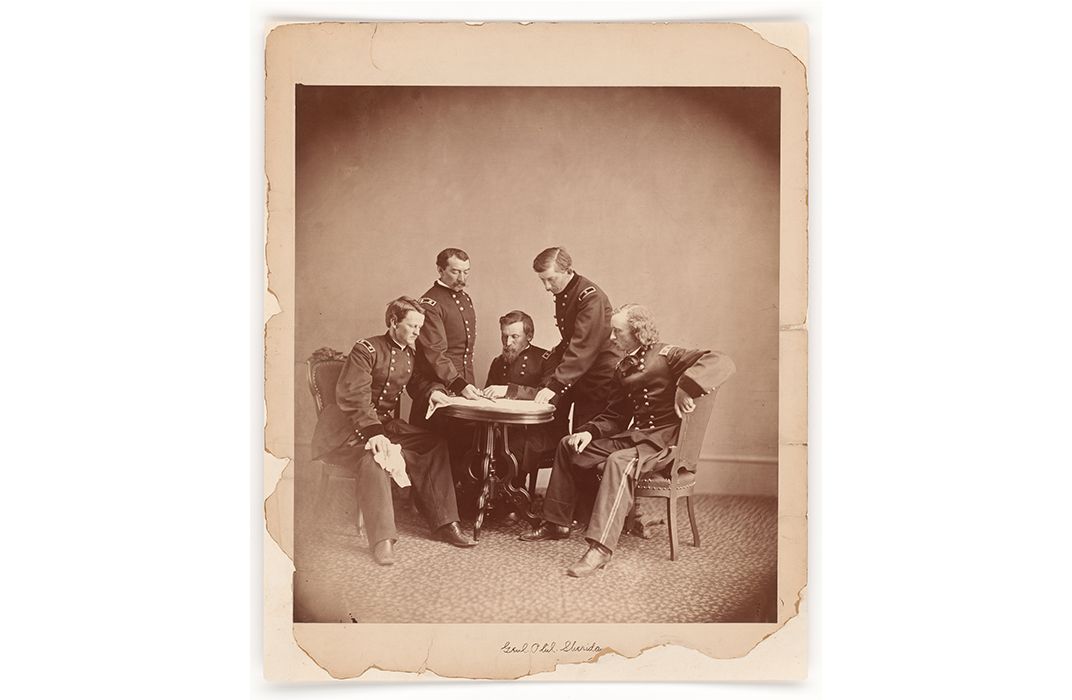

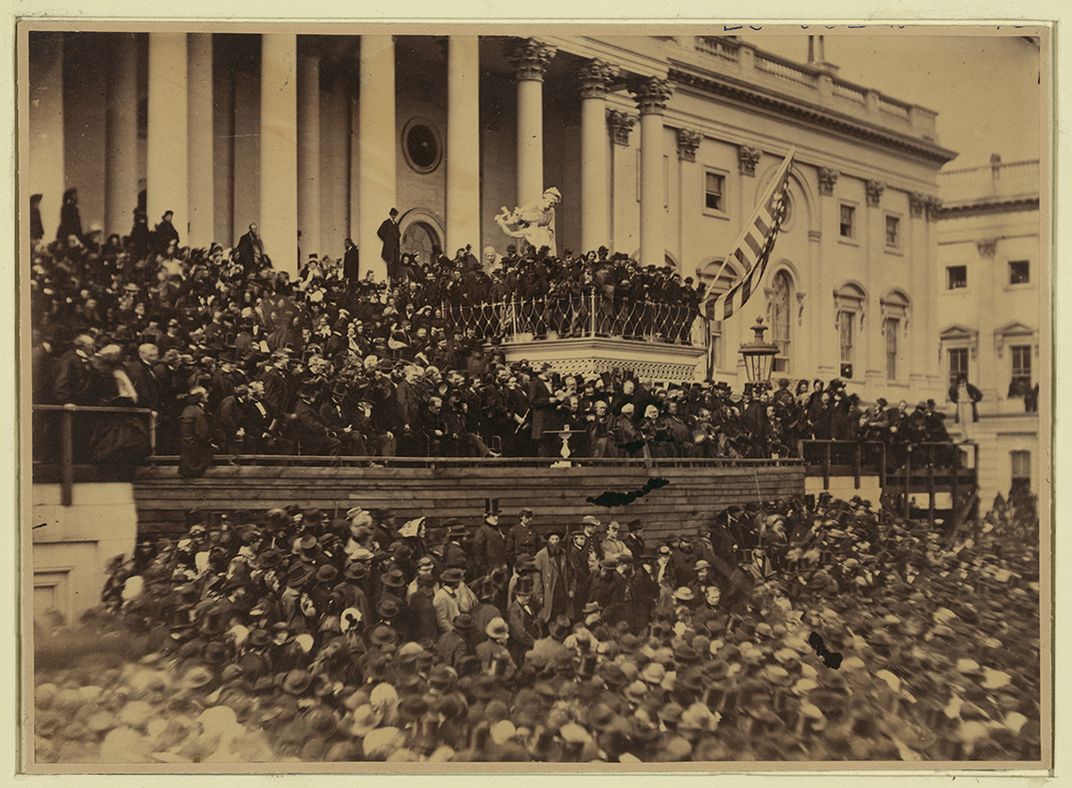

Gardner was so successful there that Brady sent him to manage his Washington, D.C., studio, and soon after that, he was photographing Abraham Lincoln as the owner of his own studio, and about to produce his historic images of the nation's struggle. But there was more—after Appomattox, unknown to most of those who have praised his groundbreaking photographs of the war, he went on to record the westward march of the railroads and the Native American tribes scattering around them.

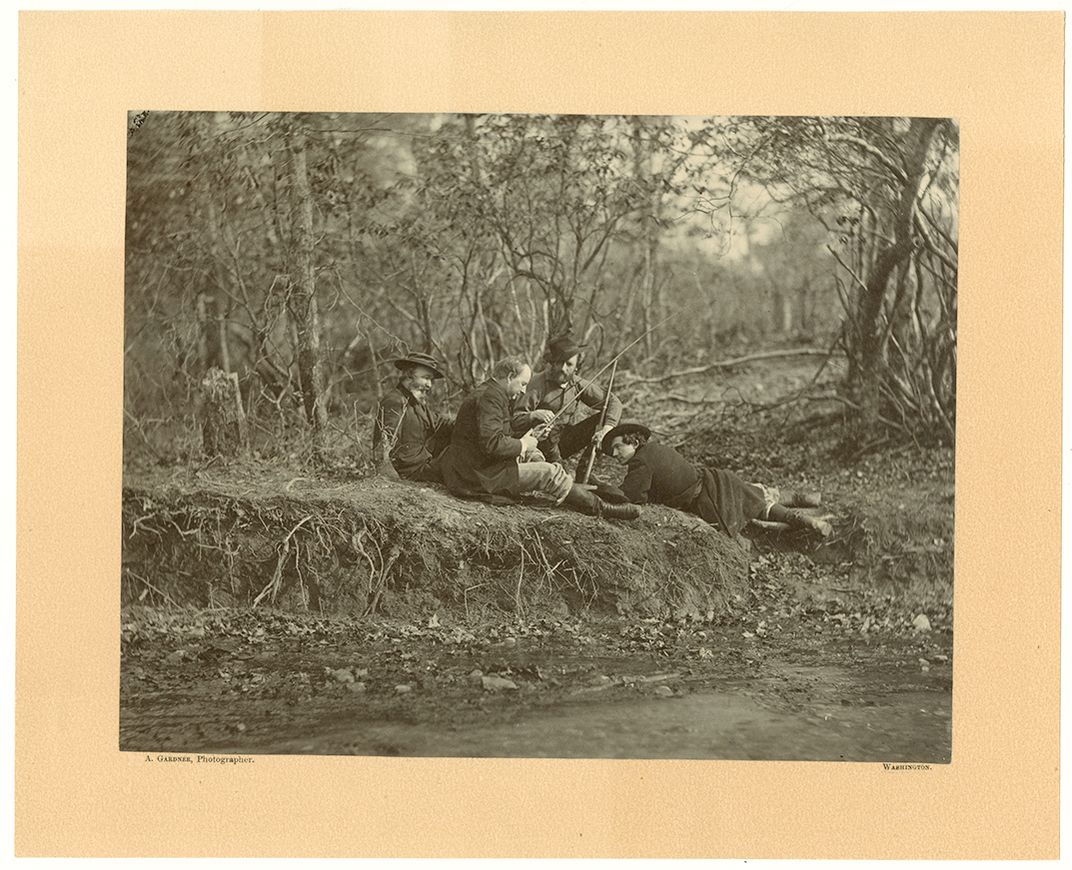

When the Civil War began, Mathew Brady sent more than 20 assistants into the field to follow the Union army. All of their work, including that of Gardner and the talented Timothy O'Sullivan, was issued with the credit line of the Brady studio. Thus the public assumed that Brady himself had lugged the fragile wagonload of equipment into the field, focused the big boxy camera and captured the images. Indeed, sometimes he had. But beginning with the battle of Antietam in September 1862, Gardner determined to take a step beyond his boss and his colleagues.

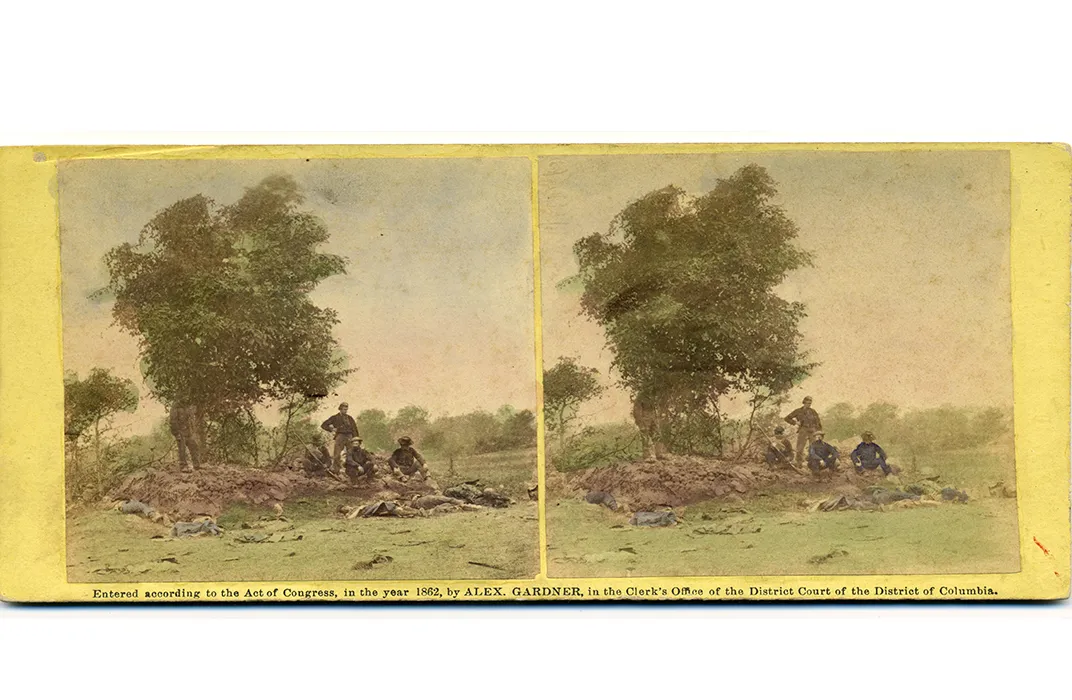

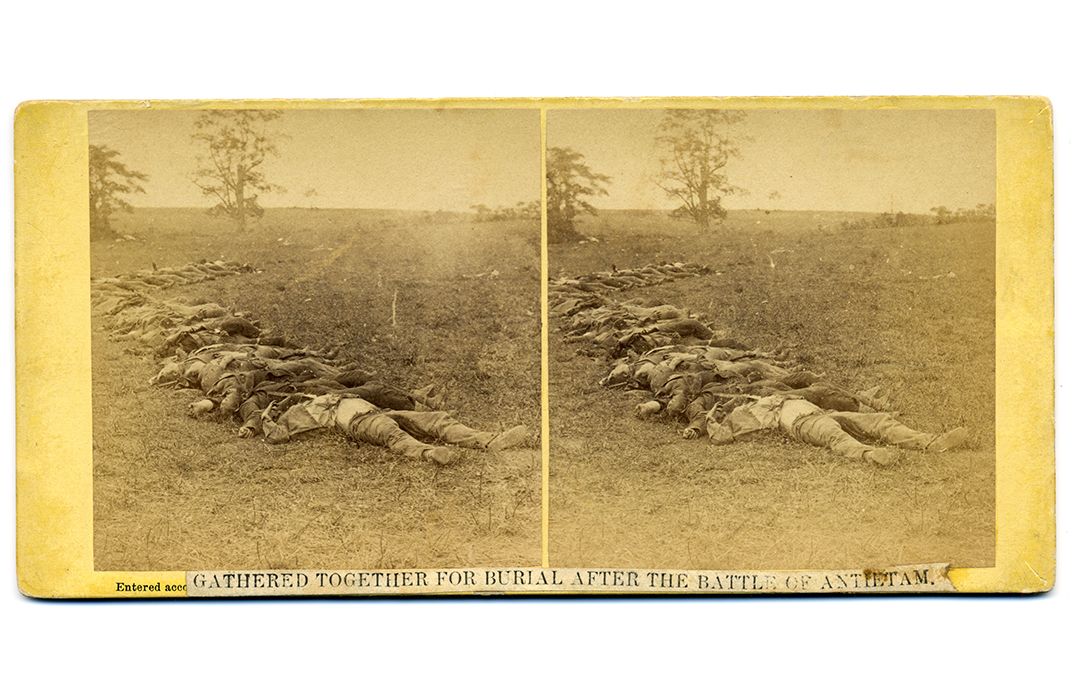

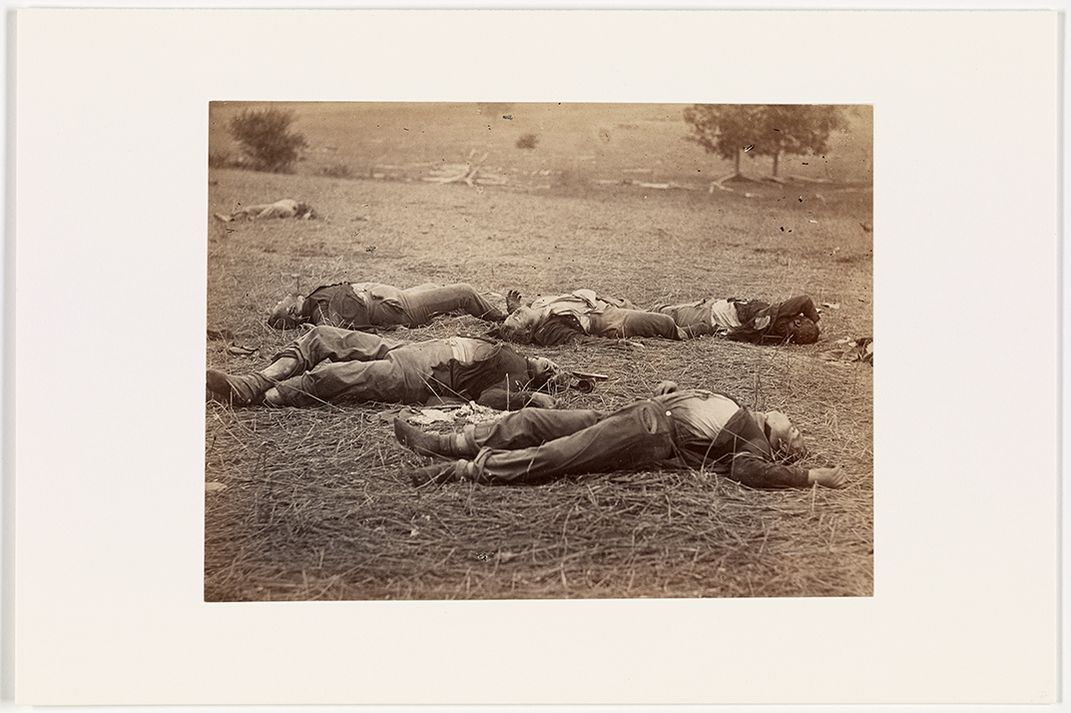

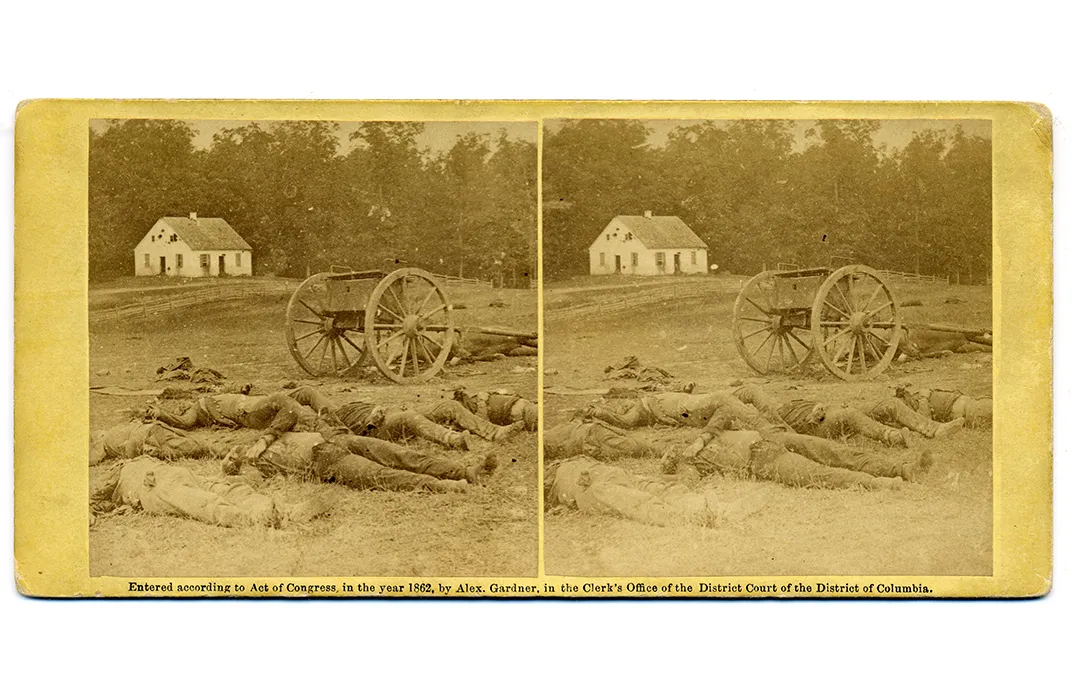

When he walked the field of Antietam, he realized that beyond the army and the overcrowded hospitals, the nation had never seen the brutal results of what was then modern warfare. With his primitive equipment, including glass plates, chemicals mixed by hand and a portable darkroom, he could not capture moving images or work effectively in low light. So he took his camera to the ditches and fields where thousands had fought and died, and pictured them as they lay sprawled at the moment of death. In the history of warfare, it had never been done before.

The impact on those who viewed Gardner’s photos was just what he hoped. The New York Times said in 1862, "Mr. Brady has done something to bring home to us the terrible reality and earnestness of war. If he has not brought bodies and laid them in our dooryards and along the streets, he has done something very like it. . . .By the aid of the magnifying glass, the very features of the slain may be distinguished."

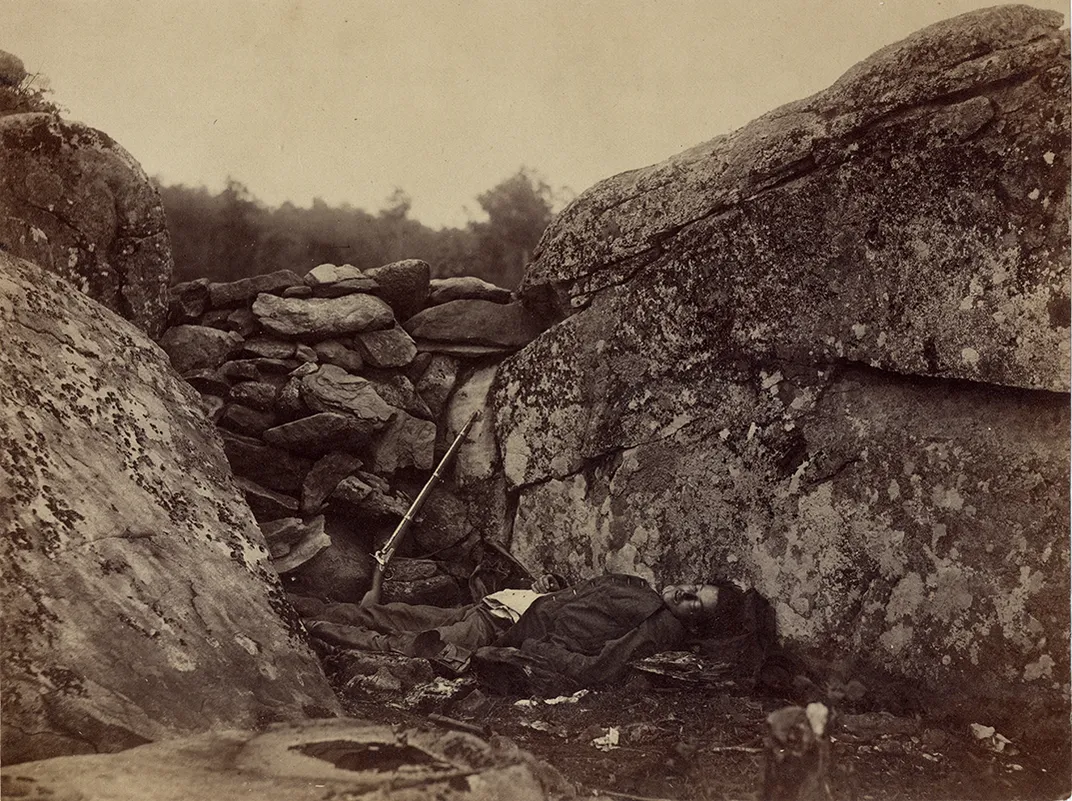

After that, Gardner broke with Brady, and in May of 1863, he opened his own studio at 7th and D Streets in Washington. He was on the field again at Gettysburg, and again he portrayed the grisly results of massed cannon and musketry. And there, perhaps for the only time, he seems to have tried to improve upon the hard facts before him. In the album he titled Gardner's Photographic Sketch Book of the Civil War, he featured one image titled "Home of a Rebel Sharpshooter."

It pictured a dead Confederate soldier in a rocky den, with his weapon propped nearby. Photographic historian William Frassanito has compared it to other images and believes that Gardner moved that body to a more dramatic hiding place to make the famous photo. Taking such license would blend with the dramatic way his album mused over the fallen soldier: "Was he delirious with agony, or did death come slowly to his relief, while memories of home grew dearer as the field of carnage faded before him? What visions, of loved ones far away, may have hovered above his stony pillow?'

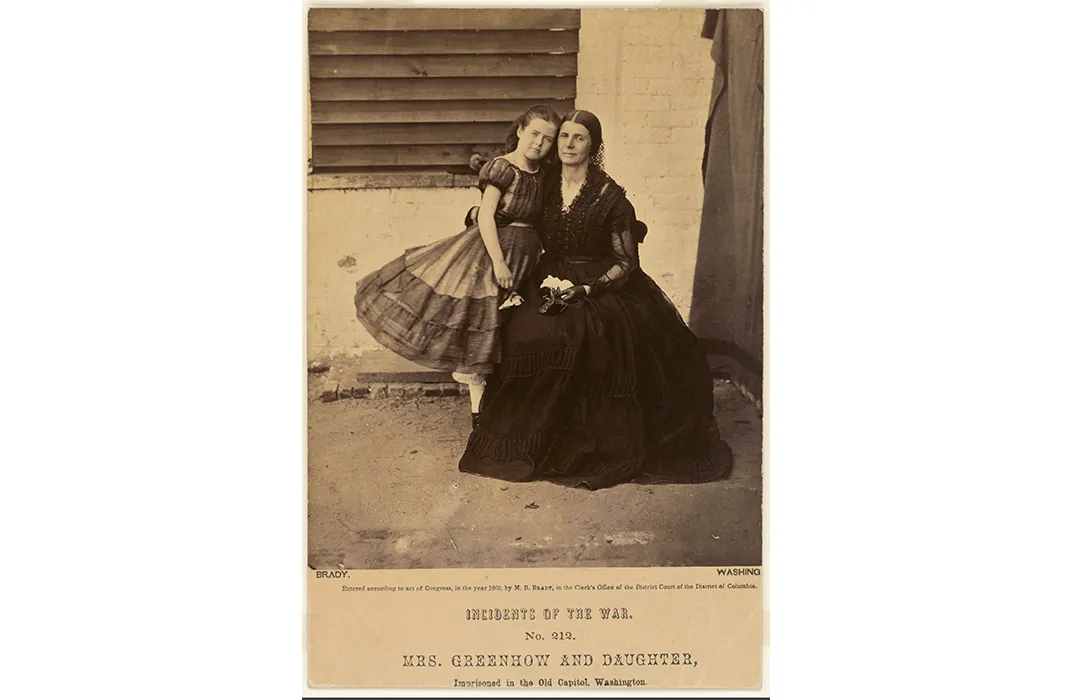

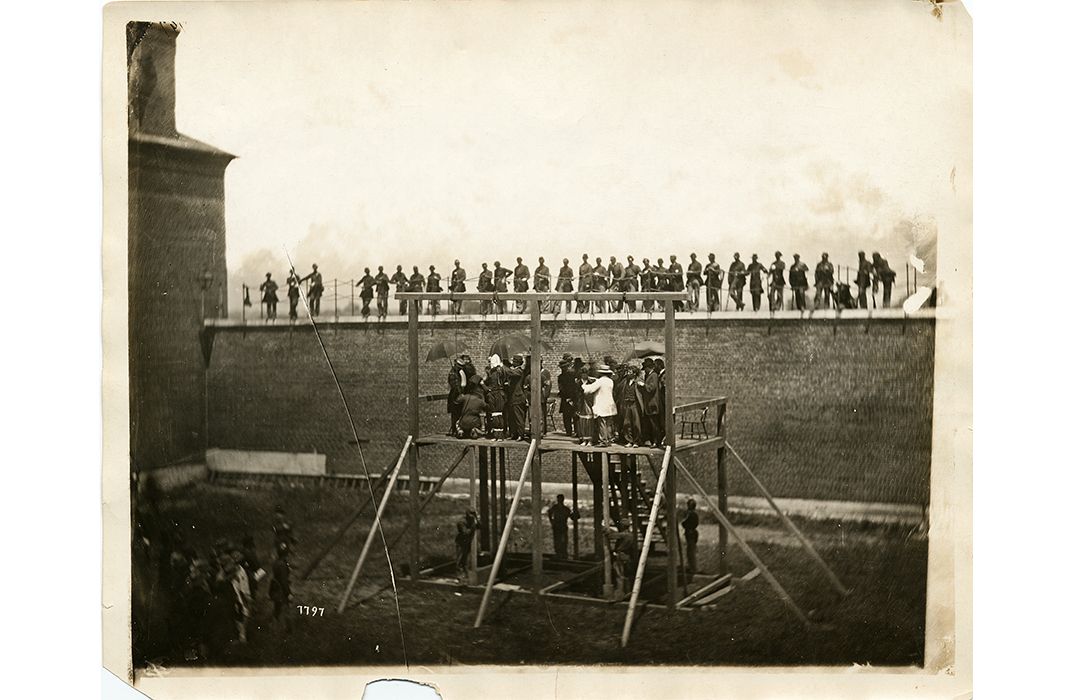

Significantly, as illustrated by that image and description, Gardner's book spoke of himself as "the artist." Not the photographer, journalist or artisan, but the artist, who is by definition the creator, the designer, the composer of a work. But of course rearranging reality is not necessary to tell a gripping story, as he showed conspicuously after the Lincoln assassination. First he made finely focused portraits that caught the character of many of the surviving conspirators (much earlier in 1863, he had done the slain assassin, the actor John Wilkes Booth). Then, on the day of execution, he pictured the four—Mary Surrat, David Herold, Lewis Powell and George Atzerodt—standing as if posing on the scaffold, while their hoods and ropes were adjusted. Then their four bodies are seen dangling below while spectators look on from the high wall of the Washington Arsenal—as fitting a last scene as any artist might imagine.

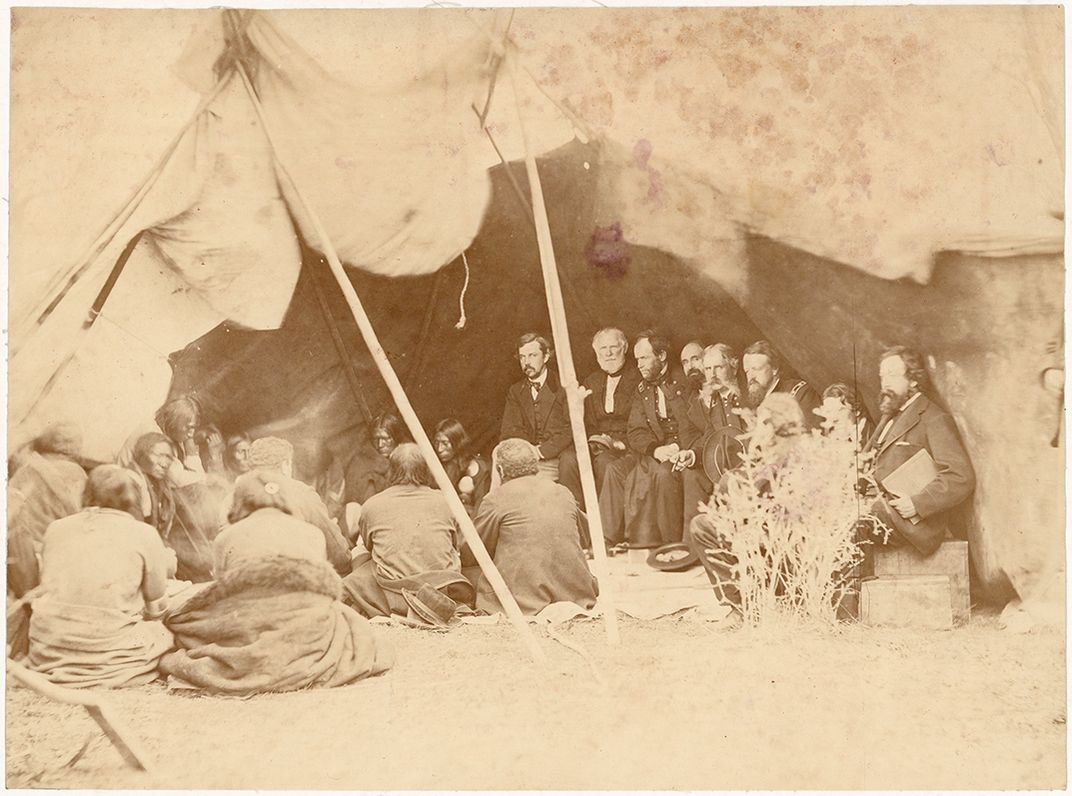

After all Gardner had seen and accomplished, the rest of his career was bound to be anticlimax, but he was only 43 years old, and soon took on new challenges. In Washington, he photographed Native American chieftains and their families when they came to sign treaties that would give the government control over most of their ancient lands. Then he headed west.

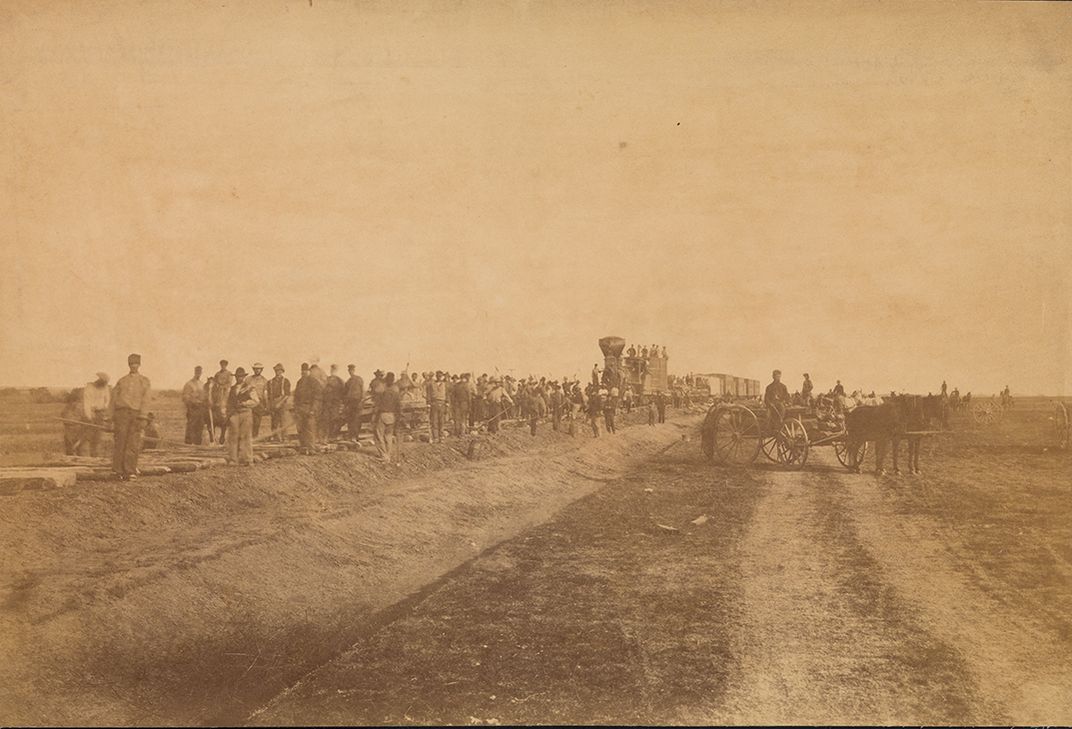

In 1867, Gardner was appointed chief photographer for the eastern division of the Union Pacific Railway, a road later called the Kansas Pacific. Starting from St. Louis, he traveled with surveyors across Kansas, Colorado, New Mexico and Arizona and on to California. In their long, laborious trek, he and his crew documented far landscapes, trails, rivers, tribes, villages and forts that had never been photographed before. At Fort Laramie in Wyoming, he pictured the far-reaching treaty negotiations between the government and the Oglala, Miniconjou, Brulé, Yanktonai, and Arapaho Indians. This entire historic series was published in 1869 in a portfolio called Across the Continent on the Kansas Pacific Railroad (Route of the 35th Parallel).

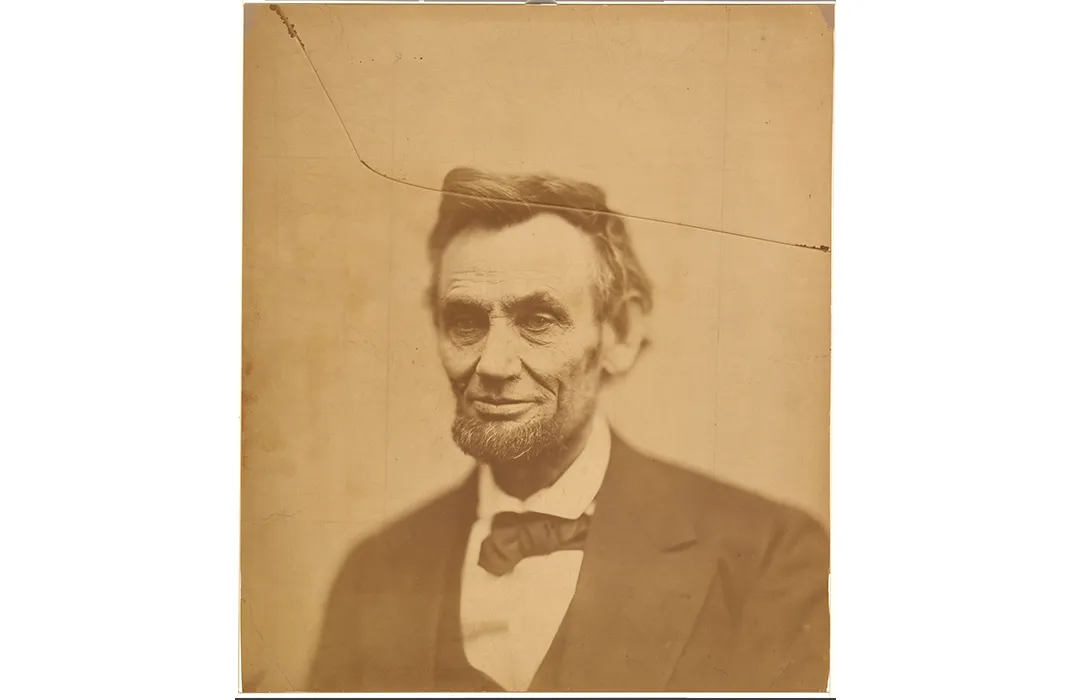

Those rare pictures and the whole expanse of Gardner’s career are now on display at the National Portrait Gallery in a show entitled “Dark Fields of the Republic: Alexander Gardner Photographs, 1859-1872." Among the dozens of images included are not only his war pictures and those of the nation’s westward expansion, but the famous “cracked-plate” image that was among the last photographs of a war-weary Abraham Lincoln. With this show, which will run into next March, the gallery is recognizing a body of photography—of this unique art—unmatched in the nation’s history.

“Dark Fields of the Republic: Alexander Gardner Photographs, 1859-1872” is on view through March 13, 2016 at the National Portrait Gallery in Washington, D.C.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/DSCN0003-001.JPG)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/ab/91/ab918a30-28a2-41f0-b5ad-d86e3f784964/npg7992-grantweb.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/c3/bc/c3bca843-44fb-439a-acc3-613f5949117e/scouts-and-guidesexh-ag-26web.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/1c/6e/1c6eab64-122f-4ba6-9d22-cd948c677747/p10139sioux-men-and-interpreterweb.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/fd/a3/fda348e9-07ee-43e3-92a5-ee3c2799486c/npg200762-gardnerweb.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/25/71/2571530f-74e7-4b62-8a3b-74dbbd5dbd5d/lincolnexhag99web.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/DSCN0003-001.JPG)