A Street-Wise Philosopher Explains What It Means to Be Homeless Amid the Pandemic

Smithsonian Folklorist James Deutsch interviews the Washington D.C. man, “Alexander the Grate,” about living in the “interstices of the infrastructure”

:focal(600x302:601x303)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/86/63/8663c199-90b6-4ae5-a0a9-505342ce85cd/alexander-the-grate.jpg)

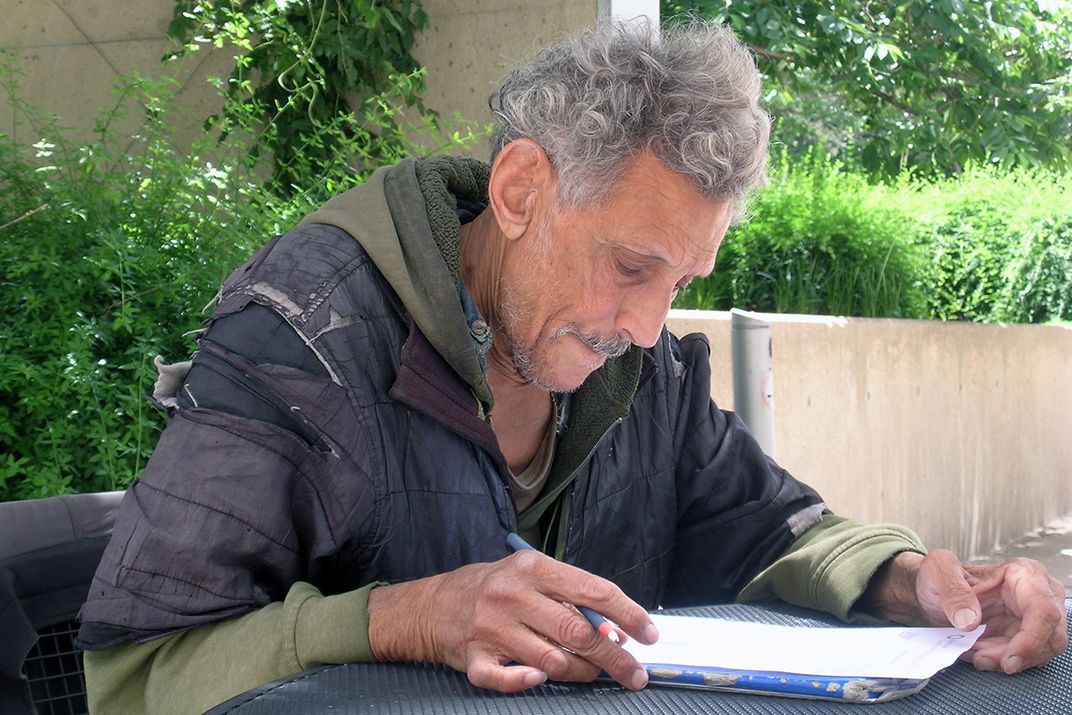

Let’s start with some basic facts about Alexander, who prefers that we not publish his last name. Alexander is a native of Washington, D.C., born in December 1948 in Columbia Hospital for Women, a graduate of Western High School in 1966; and has been experiencing homelessness since May 1981.

He has lived on various heating grates in Southwest D.C. for almost all of his homeless life, which is why he introduced himself as “Alexander the Grate,” when he and I first met in 1983. Several years ago, he told me this: “The bottom line is that the urban homeless in Washington, D.C., don’t create structures. We can’t because of the restrictions. Rather, we impose ourselves into the interstices of the infrastructure.”

Yes, that last sentence suggests that Alexander would be at home with the best of Washington pundits, except, of course, that he has no home, wears tattered clothes, and scavenges food and drink from trash cans.

Given Alexander’s longtime familiarity with members of the local homeless community, I interviewed him again in early June to learn more about how the coronavirus pandemic is affecting his own life and the lives of others in similar situations.

In his usual fashion, Alexander takes a broad perspective on the phenomenon, identifying three categories of those who are experiencing homelessness: “The Shelterites,” who by night sleep in shelters (including the missions that are run by religious organizations) and who by day may seek publicly available places to hang out; “The Independents,” who isolate themselves and rarely interact with others; “The Grate People,” who like Alexander, sleep on outdoor heating grates.

The Shelterites are still going to shelters, but have lost their main hangouts due to the pandemic. “Their daytime activities have been constrained and modified, and they are now scattered all over,” Alexander observes. Closed are the public libraries, where the Shelterites could sit all day. Closed are the indoor fastfood places, like “good old McDonald’s, where you could hang out and refill your soda continuously. There was a cluster there, [but now] all these places emptied out. That is why we are now seeing people we haven’t seen before in Southwest.”

The Independents are relatively unaffected. “There is modification, but not disruption,” as Alexander points in the case of an individual, who lives under a railroad bridge nearby. “He’s got rain cover under the underpass and with enough blankets—he can get two free blankets a night from the hypothermia van—he has survived every winter he’s been out, for at least a dozen years.”

Alexander acknowledges that this particular individual, in his space with high foot traffic and visibility, is able to maintain thanks to a strong sense of charity in the city.

“Now if you go out to California, Florida, where they’re burned out with the homeless, that’s different. But D.C. promotes taking care of the homeless because it would be a global public-relations scandal every time somebody dies of hypothermia in the capital of the richest—presumably—nation on Earth. So, he gets loaded up, and I get his leftovers, food and clothing.”

Referring to the Grate People, Alexander describes more of his own situation. In what he calls the "Before Time,” he could find copies of the Wall Street Journal, New York Times and Washington Post every workday, all left behind by rail commuters. But now, he must travel more than a mile to a location where day-old newspapers are left for recycling. “Keeping informed is a major challenge with the shutdown,” he laments.

Even more troubling for Alexander, however, are the closings of the Smithsonian museums—all of which were once his primary hangouts during the day, and even many evenings for after-hours programs.

“I am losing some of my social integrity,” Alexander admits, fearful that he may return to “a constant state of vanity, vapidity, emptiness, futility, melancholy, ennui, uselessness and sloth,” which was his condition when living in SROs (single-room occupancy hotels) in the early 1980s before he moved to the grates.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/49/75/49753fd5-f2d4-4e73-b4a3-b649d94605f4/alexander5.jpg)

What lies ahead? In his more pessimistic moments, Alexander foresees “a catastrophic world-changing, sea-changing event, like World War I, which reshaped the geopolitical conditions of the world at that time.” He compares the present to July 1914: “The archduke has been assassinated. There has been saber-rattling all through Europe, so the prevailing opinion was, this is not going to last for long. It’s just a flare-up, and it will be taken care of. Little did they know it was the worst war in human history up to that point, and it set the stage for an even worse war.”

But Alexander also sees a possible bright spot: “a scientific medical breakthrough in our understanding of how things work in nature from this virus. We are getting closer. I mean, the world is going to change when we can psychophysically enter cyberspace. The best we have now is virtual reality, but there is a cyber-conversion function that is coming. . . . There is a major paradigm shift in the relatively near future, and [borrowing an expression from filmmaker Tom Shadyac in 2012] the shift is about to hit the fan. The fan has been turned on with the coronavirus, and there’s enough stuff that’s ready to hit it.”

A version of this article originally appeared in the online magazine of the Smithsonian Center for Folklife and Cultural Heritage.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/James_Deutsch.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/James_Deutsch.jpg)