Growing up around Washington, D.C., Dave Grohl spent a lot of time in the Smithsonian museums, sometimes on school trips, other times just to get out of the summer’s heat and humidity and into their air conditioning. He was back last week to help open the National Museum of American History’s new culture wing along with its big new permanent exhibition, “Entertainment Nation.” He also received the James Smithson Bicentennial Medal along with blues guitarist Susan Tedeschi and Latin hitmakers Gloria and Emilio Estefan.

The Estefans’ careers are represented in the 7,200-square-foot “Entertainment Nation” with one of his well-worn conga and the dress she wore in the “Rhythm Is Gonna Get You” music video. Currently, the exhibition has nothing on display from Tedeschi, nor from Grohl—either from his Nirvana days or with his current band, Foo Fighters. At least, not yet.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/20/a2/20a25380-bf64-4b1b-a519-2b2e58423c15/estefan.jpg)

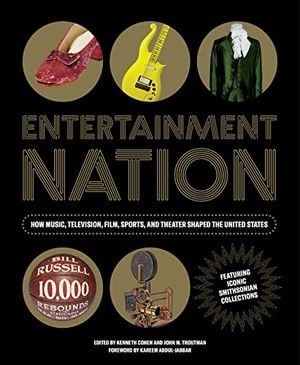

Entertainment Nation: How Music, Television, Film, Sports, and Theater Shaped the United States

Entertainment Nation offers the glitz and glamour of Hollywood, the passion and grit of star athletes, the limelight of the music industry and theater, and the amazing entertainers we love to watch.

More is to come, says John Troutman, one of the seven curators who labored for five years to create the sprawling new show, which features nearly 200 objects retrieved from the historic tens of thousands of Smithsonian holdings and covering the worlds of music, theater, sports, television and film. “Our goal from the beginning was to design an exhibition that would facilitate rotations,” Troutman says. “We plan every year to rotate most of the objects out, with new objects replacing them.” For the first initial unveiling, he says, “we strove to incorporate some of the pilgrimage objects—that people would want to come to the museum and see the most, including Prince’s Yellow Cloud guitar, one of Selena’s costumes, the ruby slippers and the Star Wars droids.

“But we also wanted to feature objects that people were less familiar with, in conversation with the more well-known stories, to reveal a tapestry of entertainment in the United States and its relationship as a galvanizing force for creating spaces for all of us to come together and also have important national conversations about who we are and want to be,” says Troutman.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/2f/dc/2fdc9acf-ec02-41b9-9448-375b703ae62f/princes-guitar-jn2021-02221.jpg)

So there are the major objects that visitors often seek out first, from Judy Garland’s ruby slippers from the 1939 film The Wizard of Oz, to the familiar silhouettes of R2-D2 and C-3PO from Star Wars: Return of the Jedi, the comfortable sneakers and red cardigan that Fred Rogers donned each day on the TV series “Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood,” and the familiar, worn chairs Edith and Archie Bunker used on the set of the 1970s TV hit “All in the Family.”

But there is no shortage of recognizable surprises at every turn, including the signpost from TV’s “M*A*S*H,” Cyndi Lauper’s dress from her She’s So Unusual album cover and early examples of Jim Henson’s puppets that the master puppeteer created for a local TV show before reaching worldwide audiences with “The Muppet Show” and “Sesame Street.” Oscar the Grouch and Elmo from “Sesame Street” are included in a display about children’s television shows alongside old favorites like Howdy Doody, dating from the mid-20th century, and today’s SpongeBob Squarepants.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/af/08/af08b755-7035-4d79-aba7-4848b8c98122/ali-wong-dress-side-jn2021-02204.jpg)

Every effort was made to reflect the rich cultural diversity that gave rise to entertainment, and the exhibition includes Selena’s performance ensemble from the mid-1990s, Althea Gibson’s tennis uniform from her 1957 Wimbledon win, the stretchy dress comedian Ali Wong wore in her 2016 “Baby Cobra” Netflix stand-up special, and Maya Angelou’s typewriter from the1980s—on view in a display of recent acquisitions near the exhibition.

Most objects are as rare as a Babe Ruth signed baseball. But others are things you may already have at home, such as Aretha Franklin’s 1972 album Young, Gifted and Black. Some still don’t quite feel historic yet, like Elisabeth Moss’ instantly recognizable 2016 costume from “The Handmaid’s Tale” and Jermaine Heredia’s colorful jacket worn while playing Angel in Broadway’s Rent in the 1990s. Other objects date much further back, such as early 19th-century sheet music from superstar opera singer Jenny Lind and paper toys depicting Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show from around the 1880s.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/d2/60/d260ee97-feb8-4050-9833-e8420c1c81e8/handmaids-tale-costume-jn2018-01468.jpg)

Two microgalleries offer sight and sound presentations. “What Is Your Anthem?” is an immersive, interactive display featuring 65 songs that have served as cultural anthems for various communities over the past century. “They’re organized thematically, and visitors can motion to select from themes that are presented to them—while they are standing on part of the stage from the Woodstock music festival,” Troutman says.

The other—titled “What’s So Funny?”—explores the history of ethnic and racial stereotypes in entertainment and the “manner by which communities of color, in particular in their stand-up and other productions, have pushed back so effectively and creatively through that medium,” Troutman says.

If Americans sometimes seem to worship their entertainment and sports idols, that sentiment is enhanced by a 14-foot stained-glass window that greets visitors. The artifact, installed in 1915 at a New Jersey plant, portrays the gramophone-listening dog, Nipper, who adorned the logo of the Radio Corporation of America (RCA) in the early part of the 20th century. Most of its colored panes were broken when the object arrived at the museum half a century ago, so the artifact has undergone extensive conservation.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/cb/58/cb5876de-b8c8-429e-9822-c32da9c26822/all-in-the-family-chairs-jn2021-00218.jpg)

From the museum’s collection of more than 5,000 musical instruments and associated objects in the new culture wing's "Hall of Music," one display case holds the makings of a dazzling jam session with a guitar from John “Bucky” Pizzarelli, a conga from Poncho Sanchez, a saxophone from Willie Smith and James Moody’s flute. A similar case features four rare Stradivari chamber instruments. Elsewhere are such recent items as a beat-up iPhone 5, which the musician Steve Lacy used to create his first solo projects using the GarageBand app.

Arrangements of objects in the glass cases make for some unexpected juxtapositions, with Jimi Hendrix’s guitar from Woodstock floating above John Philip Sousa’s baton from the early 1900s.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/37/9d/379d43c8-affd-4206-8372-f52d2253b2a5/spongebob-jn2022-00021.jpg)

Superhero fans can choose their favorite eras, from George Reeves’ original 1950s “The Adventures of Superman” costume to Julie Newmar’s Catwoman suit for the ’60s “Batman” show to Halle Berry’s Storm costume for 2014’s X-Men: Days of Future Past.

A Washington Nationals cloth face mask worn to prevent the spread of Covid-19 that leading epidemiologist Anthony Fauci wore in 2020 when he threw out a ceremonial pitch for baseball’s first game of the year is a reminder of the nation’s recent pandemic era. “The fact that he was throwing that pitch that summer, the fact there was no one in the stands, and the fact that he was wearing a Nats mask, and also signed that mask for us for the exhibition, just provided a wonderful opportunity,” Troutman says, “to tell an interesting story for us: This was how we survived—or continued to thrive—during Covid.”

The exhibition includes warm-up robes for both the professional boxer Muhammad Ali and the actor Sylvester Stallone, who played the title role in the 1976 film Rocky—raising the question of why sports is included amid the performing arts.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/43/e0/43e097ee-a265-42b8-a99b-bf6b0a78a299/staloneali1.jpg)

“It makes sense, because sports is many things. It’s this whole demonstration of a striving for human perfection physically, but it’s also entertainment. It brings us together. Everyone comes to the stadium,” Troutman says. “And it’s part of this larger world of entertainment where the lines blur. Is it television entertainment? Yes, if you’re watching it on television. And of course there’s films about sports, and music so palpably connected to stadiums, we felt it was a world we wanted to replicate in the exhibition. That’s why we didn’t create separate zones of TV and sports. We wanted to bring them all together as we all experience them today.”

Indeed, as the Estefans were given their Smithson Bicentennial Medals, named after the Smithsonian’s founder, the British scientist James Smithson, it was noted that Gloria Estefan performed at two different Super Bowls and produced and performed the closing song of the 1996 Olympics, “Reach.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/78/fd/78fd2b48-3a66-4580-a41c-ecdcf760d712/gettyimages-1447733607.jpg)

“I am speechless,” she said when she received the award. “When I was wearing that dress that’s in the exhibit, filming the video for ‘Rhythm Is Gonna Get You,’ this was not in my thoughts or dreams.”

“When we started, they said our sound wouldn’t work, and they said we had to change our last name,” Emilio Estefan said. “And we didn’t do that, because I believe in America.”

Estefan went on to become a household name—and now, the new exhibition that displays his conga is fully bilingual, under the Spanish name “Nación del Espectáculo,” with every sign and caption written in both English and Spanish.

Tedeschi, attending with her husband and co-band leader Derek Trucks, teared up as she remembered the teachers and relatives who helped her along the way. She’d go on to play the evening celebration of the “Entertainment Nation” opening in a band that would be joined by Althea Thomas, Martin Luther King Jr.’s organist at Dexter Avenue Baptist Church in Montgomery, Alabama—a pair of Thomas’ shoes are in the exhibition.

Grohl would also attend the party in the museum he loved as a kid.

“When you’re a little boy, I think you find most pleasure with the dinosaurs and the spaceships,” Grohl said, enumerating his favorite Smithsonian moments in a short interview. “I spent a lot of time over there in [the National Air and Space Museum]. But a lot of time in the Natural History Museum. But then, you know, I really started appreciating the American History Museum.

As a musician, he added, “I’ve had the pleasure of a few times taking the back-room tours, and I got to sit down to Buddy Rich’s drum set once,” he said, eyes widening. “That was something.”

“Entertainment Nation” is a permanent exhiibition now on view at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History, in Washington, D.C. The grand opening festival runs through December 18, 2022 with special panel discussions and film screenings, pop up concerts and photo opportunities. More information is available online.

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

:focal(800x602:801x603)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/31/5b/315bd1ec-202c-4c85-986c-5539a2a3b6f6/entertainment-nation.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/RogerCatlin_thumbnail.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/RogerCatlin_thumbnail.png)