The American Revolution Was Just One Battlefront in a Huge World War

A new Smithsonian exhibition examines the global context that bolstered the colonists’ fight for independence

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/d9/49/d9496a60-f252-42c6-b69e-69ff74848ed5/wsurrender-at-yorktown-painting-jnet2018-00001.jpg)

When Americans think of world wars, they picture 20th-century scenes—the blood-drenched trenches at the Battle of the Somme where a million men were injured or killed in 1916, the German blitz that rained death down on London night after night during the autumn of 1940, or the ugly mushroom cloud rising like a behemoth above Hiroshima in August 1945.

A new exhibition at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History in Washington, D.C., invites Americans to recognize another world war—one that has been traditionally envisioned as a quaint and simple confrontation between a ragtag army of rebellious colonists and a king’s mighty military force of red-coated Brits. “The American Revolution: A World War” demonstrates with new scholarship how the 18th-century fight for independence fit into a larger, international conflict that involved Great Britain, France, Spain, the Dutch Republic, Jamaica, Gibraltar and even India. “If it had not become that broader conflict, the outcome might very well have been different,” says David K. Allison, project director, curator of the show and co-author of a new forthcoming book on the subject. “As the war became bigger and involved other allies for American and other conflicts around the world, that led Britain to make the kind of strategic decisions it did, to ultimately grant the colonies independence and use their military resources elsewhere in the world.”

The roots of this war lay in the global Seven Years War, known in the United States as the French and Indian War. In that conflict, Britain was able to consolidate its strength, while France and Spain experienced significant losses. At the time of the American Revolution, other European powers were seeking to restrain Great Britain, the greatest world power and owner of the planet’s most threatening navy.

“We became a sideshow,” says Allison. Both France and Spain, to undermine British power, provided both arms and troops to the rambunctious rebels. The Dutch Republic, too, traded weapons and other goods to the American colonists. Ultimately, after struggling to retain its 13 feisty colonies, British leaders chose to abandon the battlefields of North America and turn their attention to their other colonial outposts, like India.

In a global context, the American Revolution was largely a war about trade and economic influence—not ideology. France and Spain, like Britain, were monarchies with even less fondness for democracy. The Dutch Republic was primarily interested in free trade. The leaders of all three countries wanted to increase their nations’ trade and economic authority, and to accomplish that, they were willing to go to war with their biggest competitor—Great Britain.

To the French, Spanish and Dutch governments, this was not a war about liberty: It was all about power and profit. If American colonists won their independence, that would cause harm to British interests and open new trade opportunities in North America and elsewhere for those who allied themselves with the colonists.

Inspiration for the exhibition arose from close examination of two newly restored French paintings depicting the final battle in America at Yorktown. The Siege of Yorktown and The Surrender of Yorktown, both produced by the French painter Louis-Nicolas Van Blarenberghe and on loan to the Smithsonian, offer a perspective that is unlike the most famous American representation of Yorktown—John Trumbull’s 1820 Surrender of Lord Cornwallis, which holds pride of place in the rotunda of the U.S. Capitol,

In the 1786 Van Blarenberghe Yorktown paintings, (the two on loan to the Smithsonian are copies made by the artist of the originals presented to King Louis XVI and held at the Palace of Versailles) the perspective seems peculiar. The Americans are barely noticeable on the sidelines, while the victors appear to be French. Revised copies of the paintings were made for General Jean-Baptiste Donatien de Vimeur, Comte de Rochambeau, and Americans play a secondary role in those images. In contrast, Trumbull’s take on Yorktown places American Generals Benjamin Lincoln and George Washington at center stage with the French below and to the side of the dominant figures.

Van Blarenberghe’s depiction of the French as the triumphant force, while not as true-to-life as a photograph, provides evidence of a reality missing from patriotic American stories. France, Spain and the Dutch Republic helped to make it possible for the American colonies to sustain the war, and in Yorktown, the French played a critical role in the victory by using their navy to block British ships that would have evacuated Cornwallis and his troops from Virginia.

On the other side of the Atlantic, France and Spain planned to invade Britain, and the Spaniards hoped to re-capture Gibraltar. However, Britain thwarted both endeavors before deciding to fight for India. While France faltered in trying to regain some of its Indian footholds lost in the Seven Years War, Great Britain succeeded. The last battle in this global conflict known in the United States as the American Revolution was not fought on the fields of Virginia in 1781: It occurred two years later at Cuddalore, India.

The American Revolution: A World War

“David K. Allison and Larrie D. Ferreiro’s The American Revolution: A World War is a dazzling collection of first-rate scholarly essays that rethink our nation’s founding. Instead of the parochial ‘shot heard round the world’ folklore spun about Lexington and Concord, we are served up a far more world-beat story about the 1770s. Every American should read this marvelous book.” Douglas Brinkley, Professor of History, Rice University, and author of Rightful Heritage: Franklin D. Roosevelt and the Land of America

After all fighting ended, Britain negotiated separate peace treaties with the United States, France, Spain and the Dutch Republic in 1783. While Britain maintained its dominant position on the high seas, the treaties gave the American colonies their independence, returned French prestige lost in the Seven Years War, guaranteed Spain’s holdings in the Americas as well as its trade routes, and left the Dutch Republic in a worse position in both trade and world power.

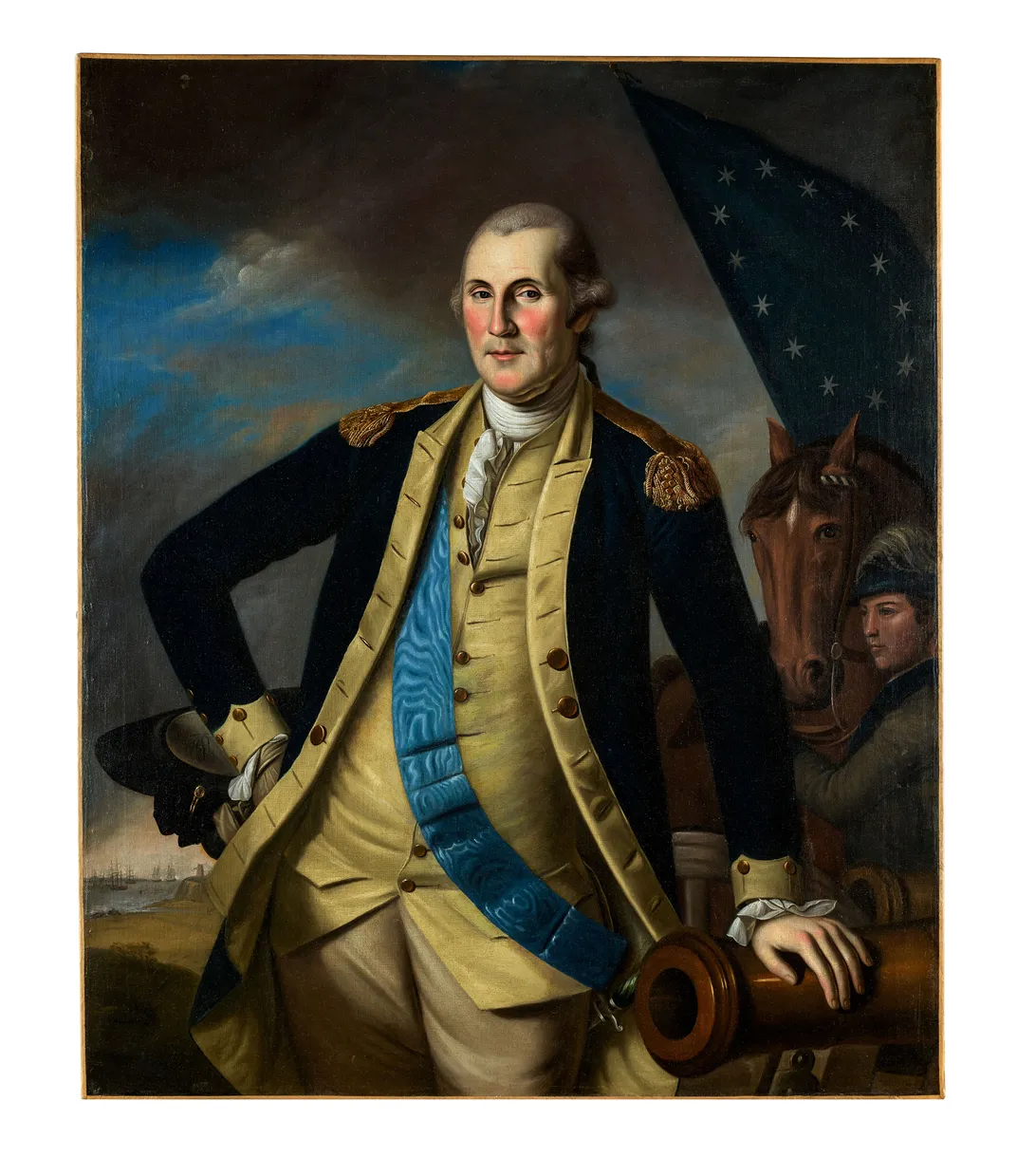

Within “The American Revolution: A World War,” interactive displays allow visitors to analyze Van Blarenberghe’s amazingly detailed paintings. On the screen, numbers indicate key images, and tapping on one will summon information that explains what the image represents and provides an eyewitness account of the surrender. Among artifacts on display will be the two paintings, which once belonged to Rochambeau and hung in his home with a portrait of Washington by Charles Willson Peale, also part of the exhibition. Other artifacts include an ornate French cannon used at Yorktown and a model of Admiral François Joseph Paul de Grasse’s ship Ville de Paris, which helped to block the British retreat.

The show also explores the public and historical image of Gilbert du Motier, more widely known as the Marquis de Lafayette. He is remembered best as a key European ally, although his actual importance to the struggle was smaller than most Americans would guess. In retrospect, it seems clear that Lafayette’s role became exaggerated because he returned to North America in 1824 for a celebratory tour. During the revolution, French officials denied the young Lafayette’s request to lead their forces in North America. The more-experienced Rochambeau made a greater contribution to the war effort and led French forces in Yorktown. Nevertheless, Lafayette cherished memories of the American battle for independence and chose Washington as a role model. Lafayette “saw himself as a kind of dual citizen,” Allison says, and allegiance to the new nation “lived in his heart.”

The exhibition includes Lafayette commemorative plates and even a kitschy Lafayette dickie, all of which were produced for his victory tour. In World War I and World War II, some Americans honored Lafayette by entering the fighting in France before the U.S. declared war. In World War I, U.S. pilots in the Lafayette Brigade flew with the French air force; items related to their service also are part of the show. These men fought to commemorate Lafayette’s support for U.S. liberty, and after U.S. troops reached France in World War I, Lieut. Col. Charles Stanton visited Lafayette’s tomb and declared, “Lafayette, we are here.”

American leaders of the 18th-century understood the international context of their revolution. As John Adams wrote in 1784, “A compleat History of the American war . . . is nearly the History of Mankind for the whole Epocha of it. The History of France, Spain, Holland, England, and the Neutral Powers, as well as America are at least comprised in it.” However, over the course of the 19th-century, American histories of the revolution minimized the allies’ role, building a nationalistic myth of raw courage and self-sufficiency that represented an early glimpse of American exceptionalism. Over the last century, awareness of the multi-faceted war has become more widely shared by scholars of that period. Nevertheless, while Lafayette never totally faded from history, the much larger global war that determined American Independence seldom finds its way into popular histories and textbooks.

“We Americans are too narrow-minded in how we view our national history, as if we alone have determined our own destiny. Yet this has never been true,” says Allison. “Our nation was formed from colonies of other nations, and the native peoples they encountered in North America. The revolution that gave us independence was in fact a world war, and battles fought elsewhere determined the outcome as much as what happened in North America. Without allies, the colonies would never have gained their freedom. Since then, development and prosperity have always been shaped by our relations with other countries, as they continue to be today. American history without the perspective of its international context leads us to false and dangerous perceptions of who we really are.”

“The American Revolution: A World War,” curated by David K. Allison, opens June 26 and continuing through July 9, 2019, at the National Museum of American History in Washington, D.C.

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Alice_George_final_web_thumbnail.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Alice_George_final_web_thumbnail.png)