Amy Henderson: American History On-Site in Washington, DC

The Portrait Gallery’s Cultural Historian Amy Henderson discusses the sites and scenes on a walking tour of Washington, D.C.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/2011120603500688525-small.jpg)

This post is part of our on-going series in which ATM invites the occasional post from a number of Smithsonian Institution guest bloggers: the historians, researchers and scientists who curate the collections and archives at the museums and research facilities. Today, Amy Henderson from the National Portrait Gallery weighs in on the sites and stories around the city of Washington, D.C.

In the rotunda of the U.S. Capitol, my students looked with wonder at the enormous, domed canvas floating overhead. What captivated them was The Apotheosis of George Washington, a 4,664-square-foot fresco soaring 180 feet above. Completed in 1865 by Constantino Brumedi, the huge painting depics a seated Washington surrounded by Liberty, Victory and Fame plus 13 maidens who are seemingly thrown in for good measure but actually represent the original 13 colonies.

The students attend a graduate class I teach at American University called “American History On-Site.” Organized around the extraordinary candy-box of museums, archives and historic sites that populate the nation’s capital, the class meets at key sites with key people to explore a city that is chock-full with history. How visitors engage with that history is our focus. At each place, the central question—who are we?—is consistent, but the ways history can be transmitted to 21st century audiences varies enormously: What is the best mix of traditional and digital? Image and artifact? Sound and light? What works best for a broad range of visitors? And, what tools should be used to engage a more specialized audience?

Our tour leader at the Capitol was the Chief Guide and Director of Public Programs for the U.S. Capitol Historical Society Steve Livengood. One of the city’s most delightful raconteurs, Livengood merrily trolled us through the Capitol’s nooks and crannies, regaling us with wonderful stories about the larger-than-life characters who have walked here before us. “Look, that’s where Lincoln sat in his one term in the House,” he said, as we walked through Statuary Hall. Past lives intersected with the present as current members of the House and Senate whizzed by on their way to meetings and votes.

As happens at the Capitol Rotunda, the sense of place can purposely evoke “awe.” The Model Hall of the Smithsonian’s Portrait Gallery, a grand space decked out in mosaic tiles, gilded mezzanines and a stained glass dome, was built as an architectural boast of the first order. When the it opened as the Patent Office in 1842, it was only the third public building in the nation’s capital, after the White House and the Treasury. The United States had barely expanded beyond the Mississippi River, but this “Hall of Wonder” was a celebration of American inventiveness, and a declaration of the nation’s Manifest Destiny to take its place beside the great republics of the past.

A sense of place can also be invented to memorialize the past. The Vietnam Memorial designed by Maya Lin is an architectural space that welds history and memory into a landscape both real and psychic. My students, born a generation after the last helicopter left Saigon in 1975, respond with quiet emotion. For them, the Wall represents something reverential.

In a totally different way, the Sewall-Belmont House near the Supreme Court has its own eccentric mix of history and memory. This was the only private dwelling that the British burned when they attacked the Capitol during the War of 1812. It was torched, my students enjoyed hearing, when someone on the second floor foolishly yelled something nasty at the soldiers marching by. Rebuilt, it became the headquarters for the National Woman’s Party in the early 20th century. Today it’s a museum about the woman’s suffrage movement, but visitors can still see burn marks in the basement—a bit of authenticity that enthralls them.

In the last decade or so, the most popular history sites have been those that have transformed their approach to visitors. The National Archives is a prime example: the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution are still displayed in a hushed and sacred space that can accommodate the legions of tourists. But now there is also a “Public Vaults” section that features lively rotating exhibits drawn from the Archive’s collections. The current exhibition, “What’s Cooking, Uncle Sam” has generated enormous publicity, healthy attendance, and even a restaurant devoted to the show and run by renowned chef José Andrés. The chef’s restaurant, located up the street at 405 8th Street, is celebrating the exhibition with a menu of traditional and historic American food.

Paul Tetreault, the dynamic CEO of Ford’s Theatre, riveted my students by explaining how he has re-invented that theater from its days as a bus-stop where tourists disembarked only to see the box above the stage where Lincoln sat beside his wife Mary, the night he was assassinated by John Wilkes Booth. In February 2012, they will open a major new education and exhibition center that focuses on the contemporary relevance of “the Lincoln legacy.” What, for example, is the meaning of “tolerance” today? Clearly, history at Ford’s is not dry-as-dust, musty old stuff anymore.

The Newseum is an exciting new addition to Washington’s museum landscape. Built near Capitol Hill, its Pennsylvania Avenue façade—engraved with the First Amendment—thrusts freedom of the press, squarely into the national sight line. Much to my students’ delight, it is also the museum with the greatest menu of history delivery systems, juxtaposing historic artifacts next to interactive kiosks, and 4D movie theaters next to segments of the Berlin Wall. Based on the idea that journalism is the “first draft of history,” it is a museum absolutely up-to-date (every day the front page of dozens of the nation’s newspapers are prominently displayed in kiosks along the sidewalk outside the building), but in the finest historic tradition as well: like vaudeville in its heyday, there is a little something here for everyone.

Today, all major history sites use social media and blogs to vastly expand their audiences. Seeing “the real thing” on-site or online still inspires wonder, whether through a historic sense of place or on Facebook and Twitter. For my students, the opportunities are huge.

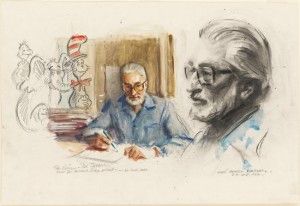

At the Portrait Gallery, there’s a color sketch of one of my favorite storytellers, Theodore Seuss Geisel—Dr. Seuss, by the preeminent portraitist Everett Raymond Kinstler. When I’m out walking this wonderful city with my students, I think of one of Seuss’ rhymes, “Oh, the Places You’ll Go!”

“You have brains in your head.

You have feet in your shoes.

You can steer yourself

Any direction you choose.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/joseph-stromberg-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/joseph-stromberg-240.jpg)