Amy Henderson: The Fashion-Forward Life of Diana Vreeland

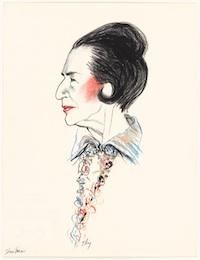

It was Diana Vreeland, whose skill, imagination and discipline, defined the job of a modern fashion editor

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/20120911010016Diana_Thumbnail.png)

Forget spectacular leaf colors and cooler temperatures: it’s the onset of “Fashion Week” in September that announces the Fall Season. Like new seasons in music, theater, dance, and art, Fashion Week signals a fresh start. What is new and wonderful? How shall we invent ourselves this time? Demure and understated? Flashy but chic? Undecided?

In addition to being a favorite sport for clothes hounds, fashion is a hot topic in the culture world these days. Project Runway has legions of fans. Yet, fashion is also emerging as a resonant topic in the museum world. Such high-visibility exhibitions as “Aware: Art Fashion Identity” at London’s Royal Academy of Arts in 2010, and the Costume Institute’s 2010 show, “American Women: Fashioning a National Identity,” as well as its 2011, “Alexander McQueen: Savage Beauty” have placed fashion center-stage in contemporary explorations of identity.

Fashion Week first premiered in 1943, the brainchild of advertising maven Eleanor Lambert. The media-savvy Lambert, whose clients included Jackson Pollock and Isamu Noguchi, had helped found the Museum of Modern Art. But her greatest passion was fashion. In 1940 she created the “International Best Dressed List” (which she would curate for decades), and in the midst of World War II, she decided it was time to de-throne Paris and declare America’s fashion pre-eminence by launching Fashion Week in New York.

At the same time, Diana Vreeland was emerging as a force of nature at Harper’s Bazaar. Editor Carmel Snow hired her in 1936, and she quickly made a name for herself with her column “Why Don’t You?” These outings were wildly eccentric, with Vreeland cheerfully asking such questions as, “Why don’t you…rinse your blond child’s hair in dead champagne, as they do in France?. . .(and) twist her pigtails around her ears like macaroons?”

During the war, Vreeland became a great promoter of American designers. Writing about the launch of Fashion Week in 1943, she extolled the “integrity and talent of American designers.” Rather than Parisian couture, she argued that the dominant style had become American, with exciting new designers standing for “American style, and the American way of life.”

Vreeland’s unblinking eye paid attention to everything that surrounded her—sartorial, literary, artistic. For her, attitude and gesture were key: “You gotta have style. . . .It’s a way of life. Without it, you’re nobody.” She put her stamp on every part of the magazine, choosing the clothes, overseeing the photography and working with the models. “I know what they’re going to wear before they wear it, what they’re going to eat before they eat it, (and) I know where they’re going before it’s even there!”

Photographer Richard Avedon, who collaborated with her for nearly 40 years, said “Diana lived for imagination ruled by discipline and created a totally new profession. She invented the fashion editor. Before her, it was society ladies who put hats on other society ladies.” With Vreeland, the focus shifted from social class to personality: “ravishing personalities,” she enthused, “are the most riveting things in the world—conversation, people’s interests, the atmosphere that they create round them.”

In her 26 years at Harper’s Bazaar (1936-62) and her near-decade at Vogue (1962-71), Vreeland conveyed her visionary sense of style through remarkable photographs. At Bazaar, she collaborated notably with Louise Dahl-Wolfe on such historic shoots as the January 1942 resort fashion story shot at architect Frank Lloyd Wright’s Arizona house “Ship Rock”—in which Vreeland herself appeared as a model—and the March 1943 cover that introduced a then-unknown Lauren Bacall, who was consequently whisked away to Hollywood to co-star with Humphrey Bogart in To Have and Have Not.

Vreeland—who always spoke in superlatives—established a distinctive look that exhorted her readers to be bold, brave and imaginative: “fashion must be the most intoxicating release from the banality of the world,” she once declared. “If it’s not there in fashion, fantasize it!”

When she left Vogue in 1971, she mused, “I was only 70. What was I supposed to do, retire?” Metropolitan Museum of Art director Tom Hoving invited her to become Special Consultant to the Met’s Costume Institute, and she quickly embarked on creating a 3-D fantasy world that wasn’t confined by a magazine spread. Lights, props, music and stage sets were all rolled out to create exhibitions that celebrated subjects ranging from the Ballets Russes to Balenciaga. Her shows were enormously popular sources of inspiration for contemporary audiences, and revitalized the Costume Institute. Before her death in 1989, Vreeland curated 14 exhibitions and successfully campaigned for the acceptance of “fashion as high art”—the idea that garments were as masterful as such traditional artworks as painting and sculpture.

In her 1980 book Allure, Vreeland dared people to live with passion and imagination. One’s creativity had to be in constant motion, she argued, because “The eye has to travel.” I asked Ricki Peltzman, owner of Washington’s Upstairs on 7th boutique and a recognized fashion curator, to assess Vreeland’s lasting impact on fashion. “Fashion is about style. It’s personal. Every day we show the world how we feel without having to say a word. And no one said it better than Diana Vreeland.”

The National Portrait Gallery’s cultural historian Amy Henderson recently wrote about Walter Cronkite and the Olympic athletes.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Amy_Henderson_NPG1401.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Amy_Henderson_NPG1401.jpg)