Amy Henderson: The Medium is the Message

The Portrait Gallery’s Cultural Historian Amy Henderson discusses the museum’s vision—to tell America’s stories as “visual biography”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/20111110115540Elvis-at-21-small.jpg)

This post is part of our on-going series in which ATM invites the occasional post from a number of Smithsonian Institution guest bloggers: the historians, researchers and scientists who curate the collections and archives at the museums and research facilities. Today, Amy Henderson from the National Portrait Gallery weighs in on the museum’s mission. She last wrote for us about cinema as art.

When PBS launched the new documentary series “Prohibition” this October, Ken Burns told a luncheon meeting at the National Press Club that his work—whether spotlighting the Civil War, baseball, or the temptations of drink—always explores the essential American question: “Who are we?”

Burns is a spellbinding story-teller renowned for using the moving image to draw audiences into his narrative web. As he spoke, I was struck by how his purpose echoed that of the National Portrait Gallery, which uses the power of images and story-telling to illuminate “who we are” through visual biography.

The wonderful expression “visual biography” emerged last year during strategic planning discussions at the NPG. John Boochever, vice chair of the Gallery’s Commission, introduced the phrase to express how the museum “brings the face of American history to life. Literally.”

“Ultimately, the National Portrait Gallery is the story of individuals and their ideas that becomes a mirror by which the country can see itself,” Boochever says. Visual biography catalyzed a strategy that made it a Gallery priority to “bring visitors face-to-face with important questions about our shared identity, our individual place within it,” he adds, “and about what it means to be an American.”

As we considered strategic ways to make “visual biography” our calling card, I thought about how philosopher Marshall McLuhan ’s idea—the medium is the message—still resonates. Each generation of media generates its own iconic cultural figures, but the key linkage at the Portrait Gallery is the one that connects the “image” medium to the “message” story.

An exhibition I co-curated last year, “Elvis at 21,” attempts to connect this link explicitly, chronicling the early days of Elvis Presley’s rise to fame in 1956 when he was 21. A journey that the young singer took from Memphis to New York is remarkably documented by the photographs of Alfred Wertheimer, who was hired by RCA to take publicity shots. Wertheimer was able to “tag along” for several months that year, and used his lens to capture Elvis’s phenomenal transition from anonymity to superstardom. His earliest photographs show Elvis walking along Manhattan streets unrecognized; momentum soars as he appears on several live television programs in the ensuing few months until, by the time of his seminal performance on the Ed Sullivan show in the fall of 1956, his audience numbers 60 million out of a total population of 169 million Americans. By the end of that year, the “flashpoint of fame” has engulfed him.

In addition to his own transformation, Elvis became a major player in the cultural upheaval that was reshaping the American landscape: Rosa Parks refused to leave her seat in the front of the bus in December 1955; Betty Friedan was still a suburban housewife, but beginning to think of the feminist struggle—“is this all?”—before she would write The Feminine Mystique in 1963.

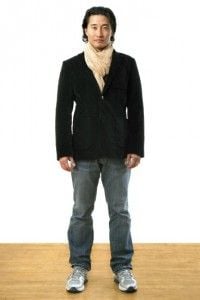

An exhibition that is currently at the Portrait Gallery, “Asian American Portraits of Encounter,” also focuses on the visual biography of identity. This show, a collaboration between the Gallery and the Smithsonian Asian Pacific American Program, showcases seven artists whose “portraits of encounter” depict the complexity of being Asian in America today. One of the artists, CYJO, focuses on contemporary Asian Americans connected only by their shared Korean ancestry. Her photographs of KYOPO–those of Korean descent who reside outside the Korean Peninsula—challenges the idea of a monolithic Korean identity by telling the stories of individual Korean Americans who each seek their own sense of “being American.” CYJO’s images are wonderfully unencumbered: she uses her lens to convey straight-forward stories of the constructed “self”—here we are, the images tell us, in our stance as contemporary Korean Americans. Change may constantly skim the surface of modern life, but KYOPO reveals something lasting beneath: above all, as CYJO writes in her text, the images connote a celebration of “modesty, kindness, and courage” in the Korean American experience. This exhibition will be up at the Gallery until October 2012.

“Elvis at 21” and “Asian American Portraits of Encounter” both exemplify NPG’s core mission to explore issues of identity and the American experience through visual biography. In whatever media, the idea of visual biography—primarily its ability to link images with their stories—establishes the Gallery as an extraordinary arena for viewing and examining the public face of “what it means to be American.”

Narrating the story of both Elvis Presley and America in 1956, “Elvis at 21″ is a collaboration of NPG, the Smithsonian Traveling Exhibition Service, and Govinda Gallery, and is sponsored by The History Channel. It is at the Mobile Museum of Art until December 4, and then will be at the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts from December 24, 2011 to March 18, 2012.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Amy_Henderson_NPG1401.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Amy_Henderson_NPG1401.jpg)