Anacostia Community Museum to Close for Renovations, but Will Tour Its Current Show With Pop Ups Across the City

D.C. Public Library will partner with the museum to bring you “A Right to the City,” which takes a deep look at gentrification and its impact

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/7c/b6/7cb6acaa-ba39-4810-9e32-1151c137658f/190222_acm_renovation.jpg)

Rosemary Ndubuizu sat on stage at a symposium last fall so crowded with scholars, activists and non-profit leaders that some at the Smithsonian’s Anacostia Community Museum in Washington, D.C. had to sit in overflow rooms so they could view the program via video. Then, she did something peculiar.

“I want us to all close our eyes for a second, and all, go ahead and take that deep breath,” said Ndubuizu, an African-American studies professor at Georgetown University, who also works with the activist group Organizing Neighborhood Equity DC (ONE DC).

“We are imagining that we have won the right to the city. We have won the right to D.C. This city is a commons for all of us, particularly the working class, to be able to control and govern what happens to the land in D.C.,” she told the room, as people nodded their heads in unison.

“Once we’ve won this and we’ve re-instituted actual Democracy, participatory Democracy, one of the things that we would immediately vote on, and I’m certain we would pass, would be making sure we rebuild all public housing and make sure housing is not for profit, but for human need,” Ndubuizu continued.

At a time when more than half of the world’s population lives in cities, at-risk populations like returning war veterans, single mothers, low-income residents, immigrants and persons of color increasingly face losing what many Americans believe to be an inalienable right—access to land, affordable housing, and sustainable, locally governed communities.

The museum’s October symposium called “A Right to the City: The Past and Future of Urban Equity,” amplified the questions raised in its ongoing and highly popular exhibition “A Right to the City.” The museum, which is closing March 15 for renovations to its building and outdoor facilities, is partnering with the D.C. Public Library to create pop-up versions of the deep look at gentrification and its effect on various city neighborhoods at branches in Shaw, Mt. Pleasant, Southwest, Anacostia and Woodbridge. There will be complementary programming specific to each community along with additional public programs in collaboration with other Smithsonian museums as well as Martha's Table and the Textile Museum at George Washington University. “With this renovation, the Smithsonian is investing not only in the infrastructure of the Anacostia Community Museum, but also in its external accessibility and overall appeal,” says the museum's interim director Lisa Sasaki, in a report.

At the symposium, presenters Ndubuizu, community organizer Diane Wong, from New York University, Amanda Huron from the University of the District of Columbia, and the symposium’s keynote speaker, Scott Kurashige, from the University of Washington Bothell, examined how urban populations across the nation are currently pivoting to use historic methods of resistance to mobilize in order to bolster local activism.

“We . . . assembled thought leaders, at this symposium, not only to get a better understanding of how the American city has been shaped by more than a half century of uneven development,” says senior museum curator Samir Meghelli, “but also how communities are mobilizing to work toward a more equitable future.”

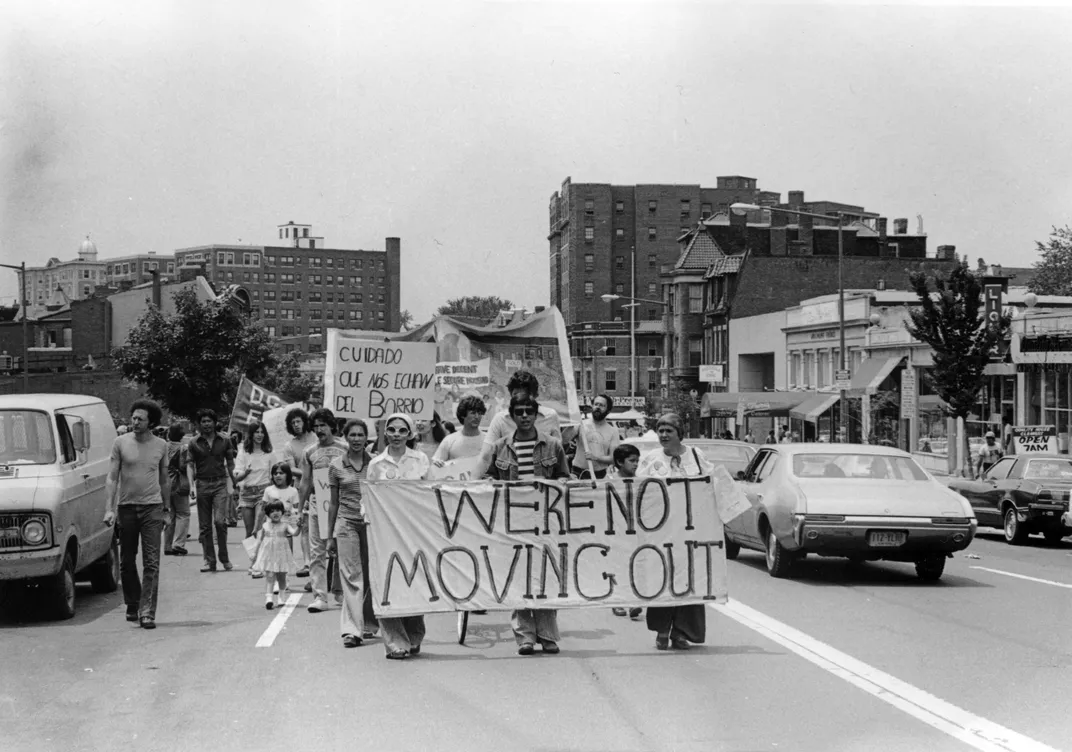

Ndubuizu recalled the 1970s in Washington D.C., and how low-income black women engaged in early waves of tenant activism and organizing with rent strikes and a citywide tenant’s union, based in Barry Farm, to push back and gain political power. “They were successful because they were thinking in political terms about building a power block,” Ndubuizu says, adding that black women understood that tenants can play a powerful role as a voting bloc. But once the cash-strapped city of Washington, D.C. went into receivership in 1995, she says the government recruited many private developers to build at will. Today’s activists are fighting to maintain the limited gains they acquired over the past 40 years, she says.

Diane Wong focuses her research on anti-displacement work in Chinatown neighborhoods in New York, San Francisco and Boston. Wong says her research shows that the rate of working class people, immigrants and people of color being displaced is on a level not seen since the 1960s, and that the percentage of Asian immigrants living in Chinatown has dropped rapidly over the past decade. Since then, she notes, all of the issues people were fighting against persist. “In Chinatown, a lot of predatory landlords have intentionally bought out tenement buildings with a large percentage of Chinese tenants, and . . . taken advantage of the fact that a lot of them are undocumented, limited English-speaking or poor, to really push them out of their homes,” Wong says. “They’ve used a lot of different tactics . . . from refusing to provide hot water, gas and basic repairs to using dangerous and hazardous construction practices.”

There’s strong pushback against the narrative that people are being pushed out without a fight, Wong points out, because residents in Washington D.C. and in other cities are mobilizing heavily at the grassroots level to confront dispossession. In New York’s Chinatown, Wong works closely with the Committee Against Anti-Asian Violence (CAAAV), which has a tenants’ organizing arm. It helps develop the leadership among low-income tenants so they can fight displacement.

The elders who have been through this work before, she said, have laid the groundwork and can use that knowledge and the same tactics that activists hope to see in the future. The W.O.W. project, located inside the oldest continually-run family business in New York’s Chinatown, has organized a series of inter-generational panel discussions around displacement as well as open mic nights and an artist-in-residency program to engage the community in conversations about changes in the neighborhood.

At the same time, there is work to be done at the national level. “The same communities are fighting for the same issues, whether it is to help access to affordable housing, to fight against police brutality and for accountability, and migrant rights,” Wong explains, recognizing that it is a continuation.

Many of the panelists brought up the legendary work of Grace Lee Boggs, a long-time activist who taught people around the nation about what she called visionary organizing: the idea that another world is not only possible, but that ordinary people are already building that vision. Boggs, along with her husband James, were integral parts of the labor and Black Power movements both nationally and in Detroit. Boggs co-authored the book, The Next American Revolution: Sustainable Activism for the Twenty-First Century, with the symposium’s keynote speaker, Scott Kurashige.

“Detroit to me is an incredible place and it changed my life to live there for 14 years because of my work with Grace Lee Boggs,” Kurashige explains. “It epitomized the Black Power movement of the 60s. The crises facing urban areas . . . begins in Detroit because the Detroit rebellion was really in many ways the biggest symbols of these contradictions that were crashing together in the mid to late 1960s. Today, Detroit in many ways still embodies the best and worst possibilities of where this country is moving.”

Kurashige says that Boggs talked often about how Detroit and other cities have faced crises because of white flight, de-industrialization, extreme disparities in wealth and power coupled with the school dropout, drugs and prison issues. “But they always at the same time recognize that people have the power within themselves and within their communities to create solutions,” Kurashige says. “The only real solutions would have to come from the bottom up.”

He points to creative ways Detroit’s working class, African-American communities worked together, including urban gardens that helped neighbors to take care of each other, and that created models for activism. Kurashige points out that urban farms eliminate blight, but often pave the way for developers to come in and promote massive urban renewal projects that drown out the voices of the people most affected by them.

The Detroit Black Community Food Security Network runs the D-Town Farm, and traces its legacy back to the Black Power movement. Kurashige says food is central not only to understanding our relationship to the planet, but it is also a big question of sovereignty and whether people have the power to provide for themselves. Since the 1960s, he argues, there’s been increased stratification, because some have increased access and others are suffering dispossession and exclusion.

“It’s reached the point that in many neighborhoods . . . and in places like Detroit, where even people’s basic human needs . . . a right to public education, to water, a right to decent housing, a right to the basic services that a city provides, these people are struggling,” Kurashige says, pointing to glaring examples like the water crises in Flint, Michigan. “We are seeing people, even or especially in wealthy cities like Seattle, being completely priced out of not just the wealthy neighborhoods, but pretty much the whole city.”

Amanda Huron reminded the crowd that the level of gentrification going on right now in the nation’s capital is similar to the 1970s. “We have lots of good organizing today and victories, but we don’t see the political will at the same level as we did in the 1970s.”

Many activists made the point that one of the lessons of the symposium, and of the exhibition, is that people need to stop thinking of power as a top down process, where the voices of the communities are drowned out by money and political influence. What works, they argue, is smaller scale plans rooted in local interests, that sometimes involves teaming with broader community groups or national organizations to get things done on a human scale. “Change comes,” says Wong, “from grass roots building across generations and developing the leadership capabilities of those across the hall, or down the block.”

The Anacostia Community Museum will close March 15 through mid-October 2019 for renovations to its building and its surrounding landscape. Improvements will be made to its parking lot and entrance and upgrades will be conducted on its lighting and HVAC system. A new outdoor plaza for group assembly and a community garden are to be built. The museum's programs and activities can be found here.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/allison.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/allison.png)