Ancient Toes and Soles of Fossilized Footprints Now 3-D Digitized for the Ages

New research suggests that for the prehistoric foragers that walked this path, labor was divided between men and women

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/1e/e2/1ee2caa2-5406-4e0c-82e7-592243448a31/88ps_topdownhirez_compleat_final.jpg)

While walking in the shadow of their people’s sacred volcano, Maasai villagers in 2006 stumbled across a set of curious footprints. Clearly made by human feet, but set in stone, they appeared to be the enigmatic traces of some long-forgotten journey.

Now scientists have teased out some of story behind those ancient prints and the people who, with some help from the volcano, left them behind. It begins while they were walking through the same area as the Maasai—separated by a span of perhaps 10,000 years.

“It’s kind of amazing to walk alongside these footprints and say, ‘Wow, thousands of years ago somebody walked here. What were they doing? What were they looking for? Where were they going?’” says Briana Pobiner, a paleoanthropologist at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History with the Human Origins Program. Pobiner is one of the scientists who has studied the prints at Engare Sero in Tanzania during the 14 years since their initial discovery.

An in-depth footprint analysis has now produced an intriguing theory to explain what the walkers were doing on the day when impressions of their toes and soles were preserved on a mudflat. Pobiner and her colleagues, in a study recently published in Scientific Reports, suggest that a large collection of the tracks, moving in the same direction at the same pace, were made by a primarily female group that was foraging around what was then on or near a lakeshore. This practice of sexually-divided gathering behavior is still seen among living hunter-gather peoples, but no bone or tool would ever be able to reveal whether it was practiced by their predecessors so long ago.

Footprints, however, allow us to quite literally retrace their steps.

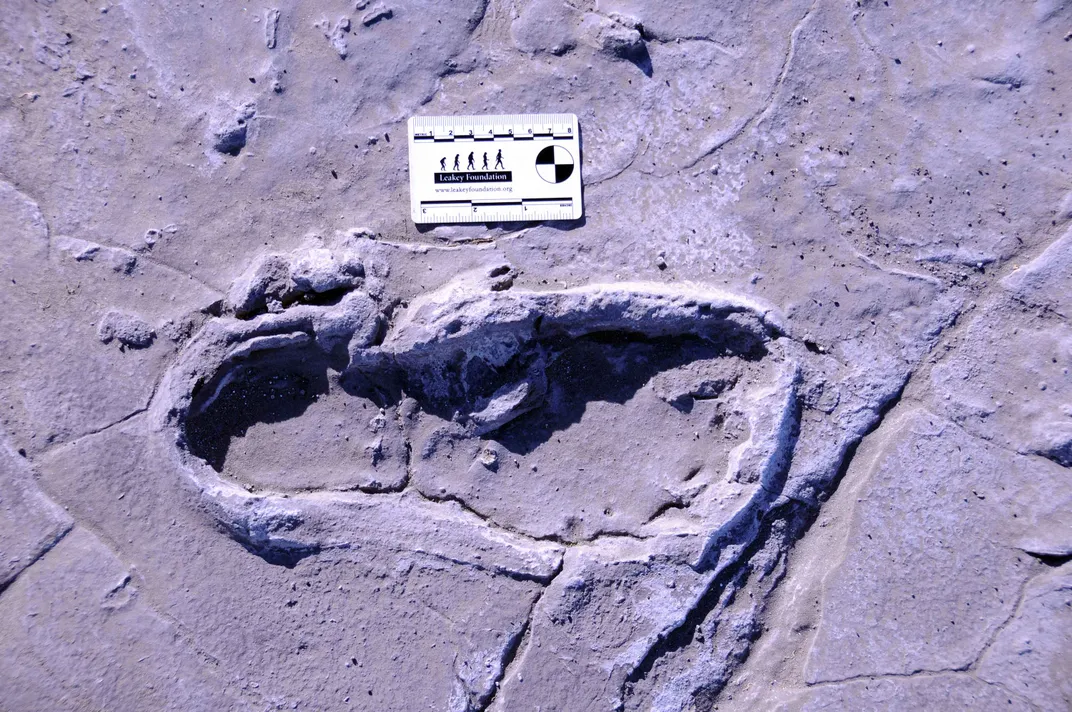

When Kevin Hatala, the lead author of the study, and his colleagues began working the site in 2009 they found 56 visible footprints that had been exposed by the forces of erosion over the centuries. But they soon realized that the bulk of the site remained hidden from view. Between 2009 and 2012 the researchers excavated what has turned out to be the largest array of modern human fossil footprints yet found in Africa, 408 definitively human prints in total. It’s most likely that the prints were made between 10,000 and 12,000 years ago, but the study’s conservative dating range stretches from as early as 19,000 to as recently as 5,760 years ago.

A previous analysis, involving some of the same authors, determined that as these people walked, their feet squished into an ashy mudflat produced by an eruption of Ol Doinyo Lengai volcano, which even today is still active and looms over the site of the footprints.

Deposits from the volcano were washed down into the mudflat. After the human group walked across and over the area, creating so many prints that scientists have nicknamed one heavily-trod area “the dance floor,” the ashy mud hardened in a matter of days or even hours. Then it was buried by a subsequent sediment flow which preserved it until the actions of erosion brought dozens of prints to light—and the excavations of the team unearthed hundreds more.

Fossil footprints capture behavior in a way that bones and stones cannot. The process of preservation happens over a short period of time. So while bones around a hearth don’t necessarily mean that their owners circled the fire at exactly the same time, fossilized footprints can reveal those kinds of immediate interactions.

“It’s a snapshot of life at a moment in time, the interaction of individuals, the interaction of humans with animals that’s preserved in no other way. So it’s a real boon to behavioral ecology.” says Matthew Bennett an expert on ancient footprints at Bournemouth University. Bennett, who wasn’t involved in the study, has visited the Engare Sero site.

Fossil footprints are analyzed by size and shape, by the orientation of the foot as it created the print, and by the distances between the prints which, combined with other aspects, can be used to estimate how fast the individual walked or ran. One of the ancient travelers who left a trackway heading in a different direction than the larger group appears to have been passing through the area in a hurry, running at better than six miles per hour.

The main group, heading to the southwest, moved at a more leisurely pace. The team’s footprint analysis suggests it most likely consisted of 14 adult females accompanied, intermittently at least, by two adult males and a juvenile male.

“I think it looks like it’s a good reflection of what we see in some modern hunter-gatherers with groups of women foraging together,” says Pobiner. Tanzania’s Hadza and Paraguay’s Aché peoples still tackle these tasks in a similar manner. “Oftentimes there is basically gender foraging, where women will forage together and men will forage together. There are sometimes mixed groups, but we often see this kind of sexual division of labor in terms of food gathering,” Pobiner says. “It doesn’t mean that these 14 women always foraged together,” she adds. “But at least on this one day or this one instance, this is what we see in this group.”

While no animals appear to have been traveling with the group, there are prints nearby of zebra and buffalo. The humans and the animals were apparently sharing a landscape that even today isn’t far from the southern shoreline of Lake Natron. Depending on exactly when the prints are made the water may have been much closer to the current site.

“It’s possible that these were just people and animals kind of wandering along the lakeshore all looking for something to eat,” Pobiner says. Other sets of footprints, like those made in northwestern Kenya, capture just this sort of behavior among ancient hominins like Homo erectus.

“They did a very nice study on a very nice set of footprints. It’s well executed and they have come up with some really interesting conclusions,” Matthew Bennett says of the research, adding that it’s a welcome addition to a rapidly growing body of scientific literature on the subject of ancient trackways.

Fossilized footprints were once thought to be extremely rare, “freaks of geological preservation,” Bennett notes. An explosion of fossil footprint discoveries over the past decade suggests they aren’t so rare after all, but surprisingly common wherever our ancient relatives put one foot in front of the other, from Africa to New Mexico.

“If you think about it there’s something like 206 bones in the body, so maybe 206 chances that a body fossil will be preserved,” Bennett says. “But in an average modern lifetime you’ll make millions and millions of footprints, a colossal number. Most won’t be preserved, but we shouldn’t be surprised that they aren’t actually so rare in the geological record.”

A famous set of prints from nearby Laetoli, Tanzania dates to some 3.6 million years ago and was likely made by Australopithecus afarensis. At New Mexico's White Sands National Monument, ancient footprints of human and beast may be evidence of an ancient sloth hunt.

Study co-author Vince Rossi, supervisor of the 3D program at the Smithsonian Digitization Program Office, aims to give these particular fossil footprints even wider distribution. His team created 3D images of the site that initially supported scientific research and analysis efforts. Today they are extending the footprints’ journey from a Tanzanian mudflat to the farthest corners of the globe.

“How many people can travel to this part of Tanzania to actually see these footprints? We’re able to give a level of accessibility to everyone,” he says. Rossi’s team has made the 3D footprints available online, and the data from a selection of prints can even be downloaded to a 3D printer so that users can replicate their favorite Engare Sero footprints.

Because 3D images capture the footprints as they appeared at a specific moment in time they’ve also become a valuable tool for preservation. The study employed two sets of images, Rossi’s 2010 array and a suite of 3D images taken by an Appalachian State University team in 2017. Comparing those images reveals visible degradation of the exposed prints during that relatively short time, and highlights the urgency of protecting them now that they’ve been stripped of the overlying layers that protected them for thousands of years.

Finding ways to preserve the footprints is a key prerequisite for uncovering more, which seems likely because the tracks heading northward lead directly under sediment layers that haven’t been excavated. Future finds would add to a paleoanthropological line of investigation that is delivering different kinds of results than traditional digs of tools or fossils.

“Footprints give us information about anatomy and group dynamics that you just can’t get from bones,” Pobiner says. “And I love the idea that there are different and creative ways for us to interpret behaviors of the past.”