The Anthrax Letters That Terrorized a Nation Are Now Decontaminated and on Public View

Carriers of the deadly anthrax bacteria, these letters—on loan from the FBI—can be seen at the National Postal Museum

“Never forget,” read the bumper stickers and T-shirts after September 11, 2001. But there was another terrorist attack against the United States that began later that month, the anthrax attacks that spread through the U.S. Mail, fueled such a complex FBI investigation and resulted in such a confusing outcome that many Americans have lost track of the details.

The first five contaminated letters were dropped in a mailbox in Trenton, New Jersey, on September 18, 2001. Those envelopes with their payloads of granular brown anthrax would take days to arrive at the addresses of the major news outlets.

NBC, CBS, ABC, The New York Post and The National Enquirer all seem to have initially ignored the strange deliveries. It wasn't until early October that the first victim, Robert Stevens, a photo editor from the company that owned the Enquirer, was hospitalized and diagnosed with anthrax.

At first, nobody connected the strange contents of the envelopes with illness. Government officials played down the possibility that this was the work of a terrorist. “It is an isolated case and it is not contagious,” said Tommy G. Thompson, then Secretary of Health and Human Services, at a White House briefing on October 4. “There's no evidence of terrorism.”

“Anthrax happens,” said a spokeswoman for the North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services.

Government officials stuck to this position even as anthrax panic swept a nation that was (and perhaps still is) waiting for a second shoe to drop after 9/11. People began stockpiling Cipro, an antibiotic that is typically recommended for the treatment of anthrax. Talk swirled about the possibility of a large-scale anthrax attack. What if it was scattered over a city? Blown into the ventilation system of a skyscraper?

Surprisingly, the original anthrax letters were not destroyed. After a thorough decontamination process, several of the letters have been loaned to the Smithsonian's National Postal Museum in Washington, D.C. and are on view in the exhibition, "Behind the Badge: The U.S. Postal Inspection Service."

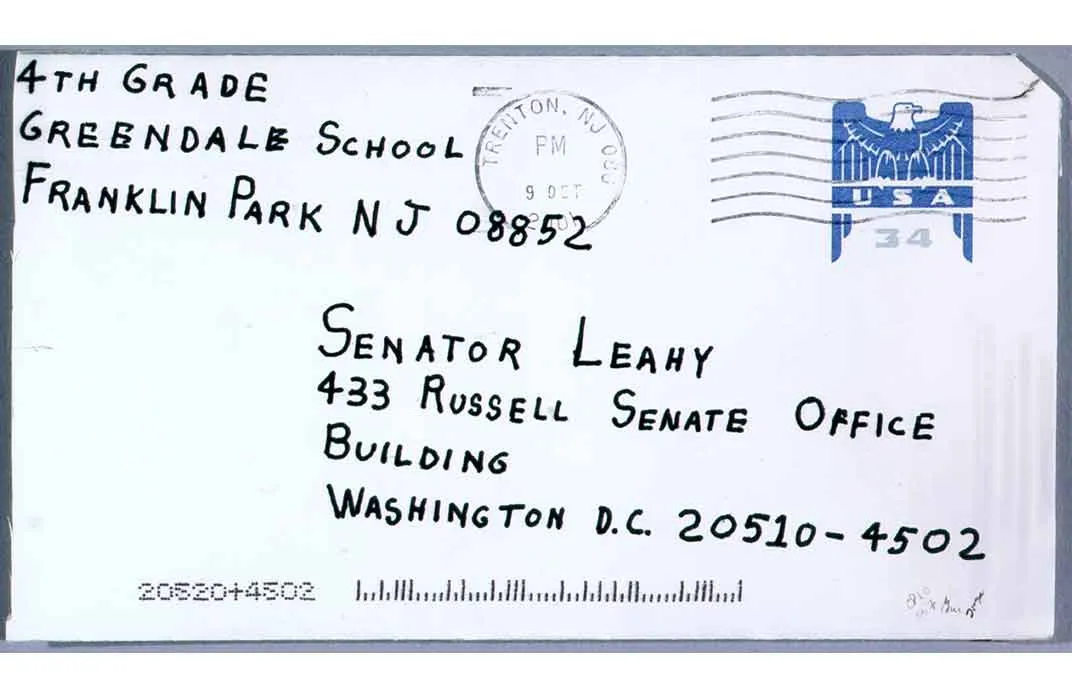

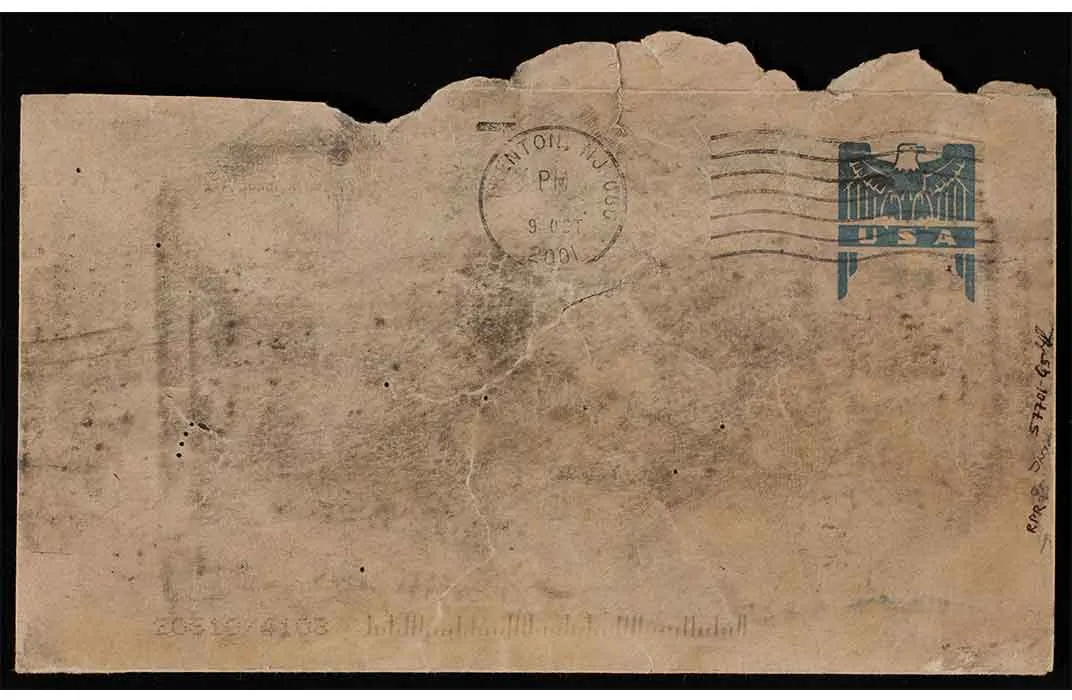

“We have letters to Senators Patrick Leahy and Tom Daschle and Tom Brokaw (envelopes & letters) on loan from the FBI,” says Nancy Pope, head curator of the museum's history department. “Because of their extremely fragile condition we have them in a special case that only lights up when a visitor activates it and are only displaying one at a time.”

The museum also displays the mail collection box that the terrorist placed the letters in as well as an American flag which had hung in a mail processing and distribution center where two postal workers, Joseph Curseen, Jr. and Thomas Morris, Jr., were fatally infected.

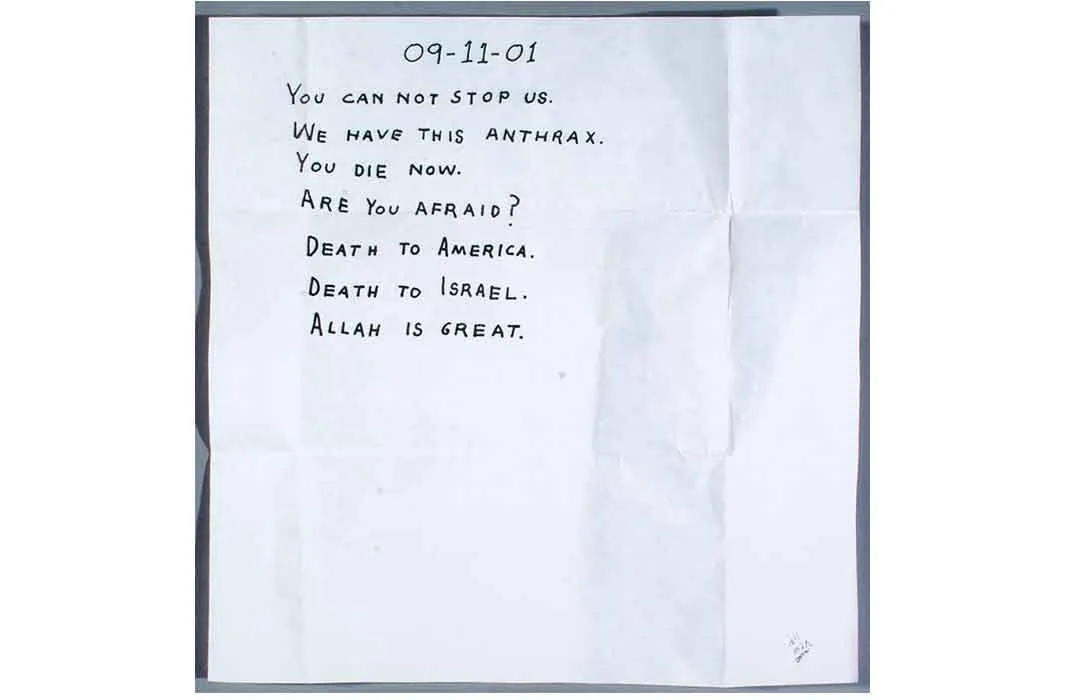

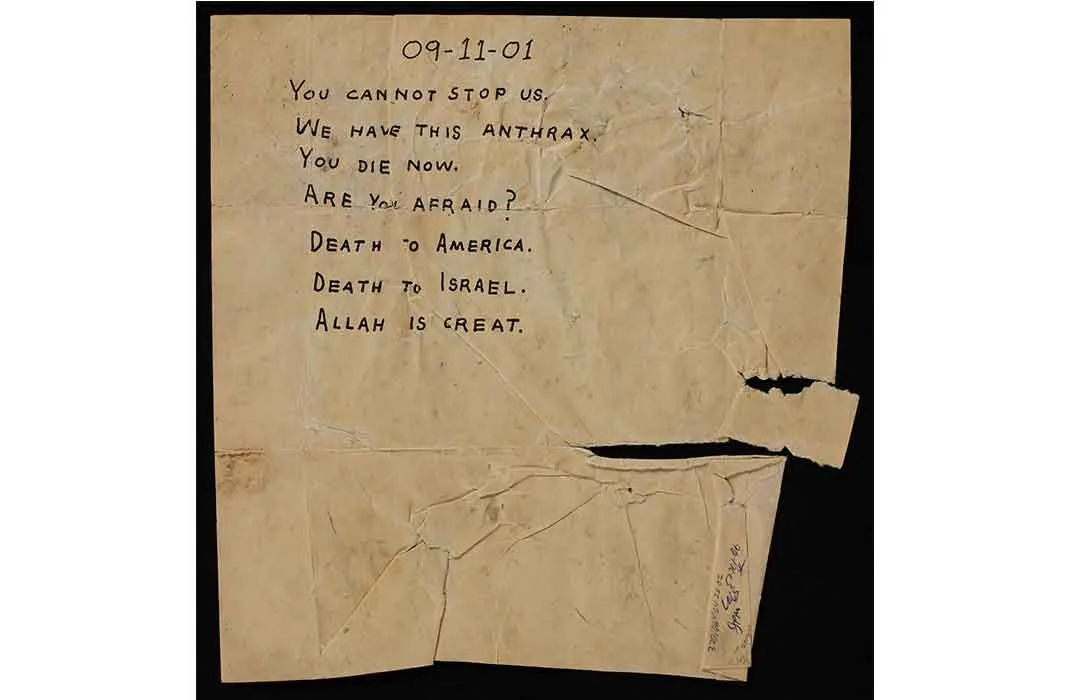

The question of terrorism was settled beyond a doubt when a second mailing of anthrax envelopes was addressed to the pair of senators, including then-majority-leader Tom Daschle (D-S.D.) with a terse, hand-written letter that famously included the line, “we have this anthrax.”

The letter to Daschle was opened on October 15 by intern Grant Leslie, who is now the managing director of a lobbying firm.

“It looked like baby powder,” Leslie said in an interview on the PBS program, “Frontline.” “I was wearing a dark gray skirt and black shoes, and you could see it, just vividly, on the dark colors.”

Leslie was the first victim to see a more highly refined version of the powdered anthrax that could easily be inhaled. She was treated with antibiotics and did not become sick. But a total of 22 people did get sick with anthrax and five died.

Now that it was undeniable that terroristic anthrax attacks were underway, a mild panic set in. Large volumes of mail were quarantined by the United States Postal Service as some postal employees became infected. Checks, bills, letters and packages simply stopped arriving. For many people and businesses that had resisted the cultural shift to email, this was the moment that pushed them online.

Even once the mail started moving again, many Americans were too afraid to open an envelope with a return address they didn't recognize. Businesses and government agencies purchased glove boxes to allow employees to open mail without contacting the contents. Smithsonian magazine's then-editor Carey Winfrey had to reassure readers: "Fear not," he wrote in 2002, "the magazine itself is mailed to subscribers directly from our printing plant in Effingham, Illinois."

With a mid-term election only weeks away, officials in the Bush White House pressured FBI director Robert Mueller to publicly blame Osama bin Laden. That theory fell flat. Weaponized anthrax capable of causing infections through the lungs is a sophisticated substance requiring advanced laboratories and highly specialized scientific skills. It couldn't have been made in a cave in Afghanistan.

Other investigators and politicians tried to pin the blame on Saddam Hussein's government in Iraq. Some people imagined a lone, unibomber-type culprit.

Meanwhile, the thrash metal band, “Anthrax,” found themselves in an awkward position. They had been using the name without controversy since 1981 but were being attacked in the media for appearing insensitive. The band issued a press release suggesting that they change their name to "Basket Full Of Puppies."

Before the tragedy of September 11th the only thing scary about Anthrax was our bad hair in the 80's and the "Fistful Of Metal" album cover. Most people associated the name Anthrax with the band, not the germ. Now in the wake of those events, our name symbolizes fear, paranoia and death. Suddenly our name is not so cool.

Hoping to help anyone searching the internet for medical advice about anthrax, they also temporarily changed the band's website (anthrax.com) to contain information about the spread and treatment of anthrax.

Copycat hoax letters were sent, but the letters sent to the Senate were the last of the real anthrax mailings. Nobody knew this at the time. Years of public paranoia about the mail would follow, gradually tapering off as new cases failed to materialize and a war in Iraq gave Americans new problems to worry about.

During the course of a seven-year investigation, a prime suspect eventually emerged. Bruce Edwards Ivins, a government biodefence researcher who worked with anthrax. He committed suicide in July of 2008. Soon after, the Justice Department explained the convincing case that they had intended to bring against him.

Curiously, the government archive of anthrax samples that could have quickly demonstrated a genetic link to the anthrax used in the attacks had been destroyed immediately after the first infection was detected.

Many of the victims of the anthrax attacks were postal employees who were exposed to the powdered anthrax as the envelopes moved through sorting machines. More than any other group in America, postal employees were terrorized by Ivins' attacks. The rest of us could choose not to handle mail. Postal workers had to spend eight hours a day surrounded by it.

While the attacks of 9/11 are explained to new generations of Americans, the story of the anthrax attacks isn't taught in school and probably never will be. Certainly far fewer people died from anthrax than by hijacked airplanes, but the anthrax letters caused a national panic which was felt by everyone in America for over a year. It was a major part of the post 9/11 atmosphere of foreboding and paranoia which, in all honesty, perhaps most of us wanted to forget.

The exhibition “Behind the Badge: The U.S. Postal Inspection Service” is on view indefinitely at the National Postal Museum in Washington, D.C.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/JacksonLanders.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/JacksonLanders.jpg)