Architect James Wines Talks Putting a Chapel in a Denny’s and Making Art from Garbage

The outsider architect-artist has finally wooed the establishment, winning the Copper-Hewitt’s Lifetime Achievement Award, but he’s still mixing things up

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/20130605093132Dennys-Thumb.jpg)

There’s little that James Wines hasn’t done. The highly acclaimed architect has designed commercial showrooms and fast food chains, museums and parks, and is currently working on a cemetery in South Korea. He wrote one of the early tomes on green architecture, urging practitioners to look for holistic and not just technology-driven solutions. With a background in visual arts, Wines founded his firm, SITE (Sculpture in the Environment) in 1970. His willingness to take on any and all projects, from high concept to mainstream often put him at odds with the design world. Despite winning a slew of awards, including the Pulitzer Prize for Graphic Art, and grants, Wines says he’s remained somewhat of a thorn in the side of the industry.

For his pioneering work in green architecture and his dedication to erasing boundaries in the practice of architecture, Wines was awarded the Cooper-Hewitt’s 2013 Lifetime Achievement Design Award. He says the award, which requires nomination from peers, is a triumph. “First of all, the fact that our government endorses it is a huge jump in the award arena,” says Wines. “It’s good to feel that there’s this national recognition in the design world, it’s a terrific honor, there’s no question about it.”

“We’ve done environmental art, we’ve done architecture, we’ve done work for MTV, work for the rock ‘n’ roll industry, we’ve done products,” says Wines. Because of this, he says, “I’ve always been considered outsider or marginal or alternative.” It’s a stance he never particularly sought out, but he certainly doesn’t eschew.

We talked with the rule-breaker about his career and some of his landmark projects.

So when you founded SITE, you weren’t setting out to turn everything on its ear?

Well, not really. You have sort of a vision. I came from visual art. We all lived on Green Street–somebody called it the Green Street Mafia for environmental art because we had Robert Smithson and Mary Miss and Gordon Matta-Clark and Alice Aycock and everybody converged on one street in Manhattan and it was a dialogue. I think artists were trying to escape from the gallery, you wanted to get out into the streets, you wanted to get where the people are, the idea of hanging pictures or putting sculptures on pedestals it was kind of anathema to my generation.

It’s kind of a suicidal mission, you know. I have coffee with Alice Aycock every morning because she lives right across the street and we’re always commiserating about all the wise artists who continued painting small paintings and did well. We’re always struggling with building departments.

With that background, what does architecture mean to you?

There’s the building, but then there’s the courtyard and the streets and it all flows together.

People in my office always criticize me because no matter how small it is, I get interested in it, because you realize that everything can be transformed or everything could be made more interesting than the norm.

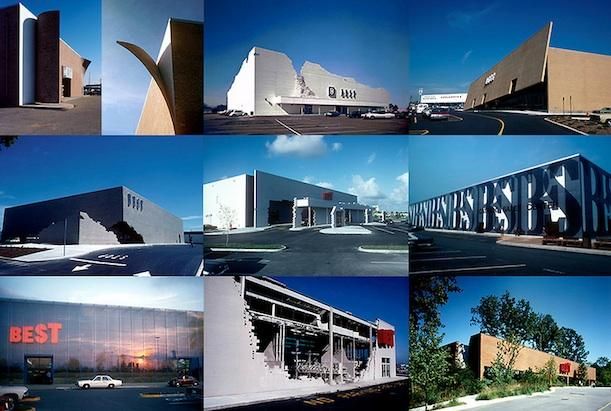

We started in the junk world, with buildings no self-respecting Harvard student would stoop to design, which is shopping centers. But we always say we bring art where you least expect to find it. These are places where you would never expect to find good design or architecture or anything else and we made that transformation.

A recent example of that is the Las Vegas Denny’s, which includes a chapel.

Denny’s is very amusing. Nobody can possibly believe that Denny’s as a corporation, given their history, that they would ever be interested in art. But I always point out, they were the original Googie style. They were really part of that real strip diners, which we now admire today as being historic artifacts. There are whole books on diner style. So it obviously became respected after the fact, but there’s always this association that no self-respecting architect would touch that, so I’ve always liked those things.

There’s this wonderful statement about Picasso I read when I was in school and I agree so much; he said, you don’t make art out of the Parthenon, you make art out of the garbage under your feet. And it’s so true, you look where other people don’t look.

You’ve attracted your fair share of criticism, what do you make of it all?

I was on a panel of artists whose careers started with totally negative criticism, this was 30 years ago, but it was Claus Oldenburg, Roy Lichtenstein and Frank Stella and all these accusatory early criticisms. I was still in school and Roy Lichenstein had his first show and the headline in was, ‘Is He the Worst Artist in the U.S.?’ So we all collected our negative criticisms and all these horrible things that were said, particularly by the architecture world–this isn’t real architecture and it won’t last.

Not only did all the people last on the panel, but they lasted a lot better than others. I remember Frank Stella at that time was doing his black pinstripe paintings and he was saying, why do the critics always start out with what you’re not trying to do, instead of trying to critique what you are trying to do.

So how did you survive?

I guess just will power. I think if you can hang in there, what did Woody Allen say, the key to success is showing up? It’s so true. You just keep showing up. But we had good clients. We started with art patrons, which is a good way to start. Young architects always say how did you get started and I say, well I worked with my connections in the art world. So we started with two or three clients who were really art patrons. They weren’t questioning the value of doing it. They weren’t questioning whether it’s architecture.

Later on, when you start getting normal clients, that’s more difficult because you can’t use this esoteric verbiage.

One of your most popular projects is the Shake Shack in New York City. Why are people so crazy about this?

I have no idea. That’s a phenomenon because it was kind of a “let’s see what happens.” That’s a real saga because New York City fought that: you can’t put a commercial enterprise in a park. When they found out there were foundations under there, built in the 19th century, to receive exactly that kind of kiosk, then they couldn’t say anything. City Hall backed down.

One thing led to another and I think it’s our most famous and most beloved project.

Anybody who comes to New York to see me, one of the first things they say is, will you take me to the Shake Shack. It’s iconic I guess. It’s ironic, because the building is sort of the menu in a way. And it’s also highway art in the middle of a lush park. We’re using sort of this hybrid in between a park and a highway.

I took some Iranian students and they stood in line. I said, I’ll sit down, you stand in the line. And they stood in line for an hour. And they were so excited: we got to stand in line! As a New Yorker, I can’t possibly imagine that psychology.

An earlier project in Chattanooga introduced some really high concept bridges into park space, how were those received?

Very well. They messed it all up now, they kept invading it. It used to be the park and then there were small shops around it, it was really nice, very human-scale. Now they’ve got bigger and bigger buildings.

But it was very well-received at the time. The old people sit in the summer under the arches, which are cool and they can watch the children. There were lots of people-watching situations and water and it had all the ingredients of a pleasant public space. All the trees and bushes have grown out, it’s a lush place.

What’s next?

My big interest is still in public space. I would love to do something in New York. Other than the Shake Shack, we’ve never done anything in New York.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Leah-Binkovitz-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Leah-Binkovitz-240.jpg)