The Army Veteran Who Became the First to Hike the Entire Appalachian Trail

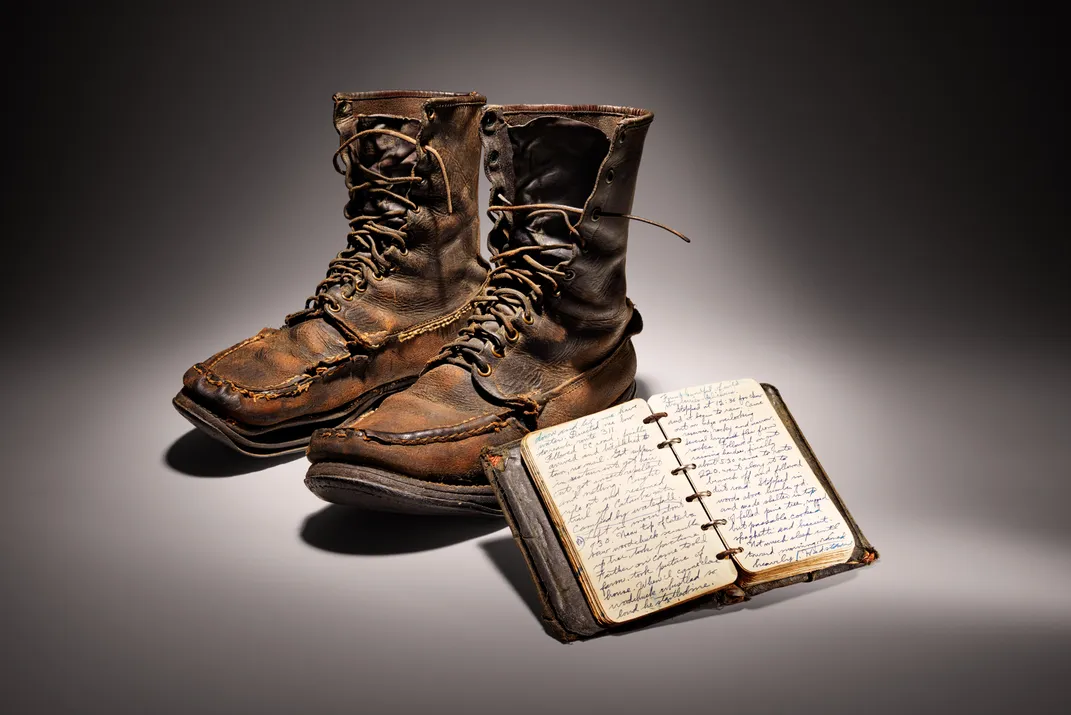

His journal and hiking boots are in the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History

Carry as little as possible,” Earl Shaffer said. “But choose that little with care.”

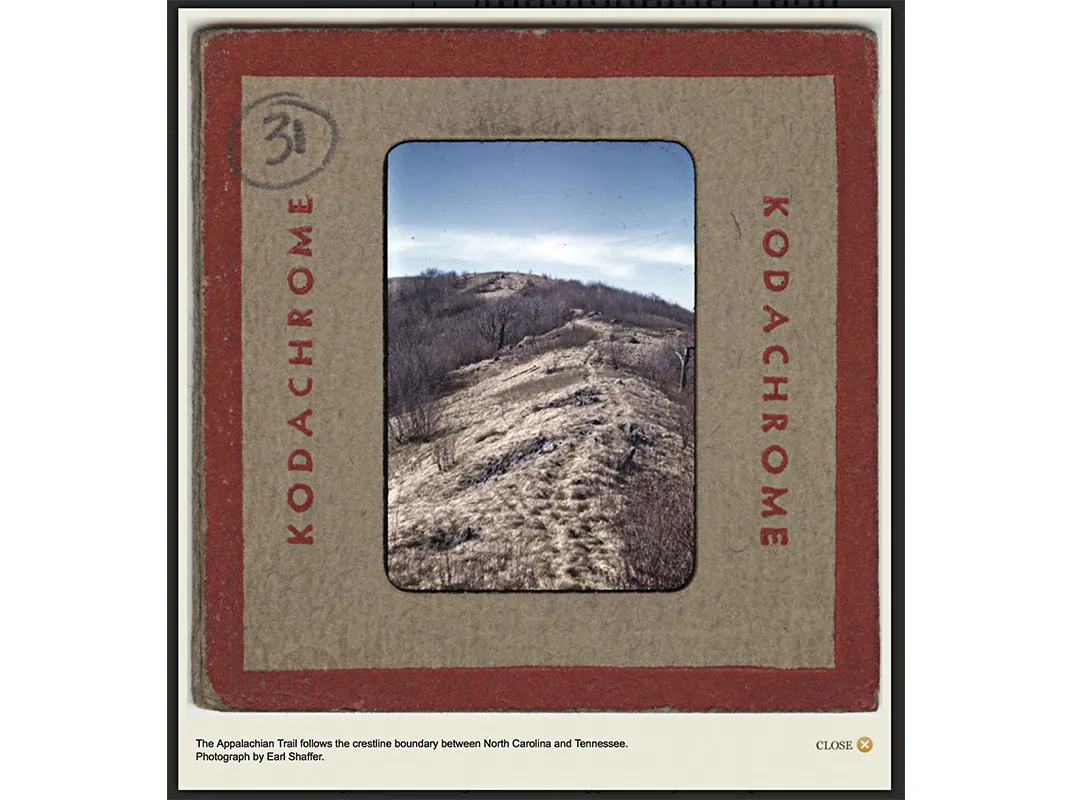

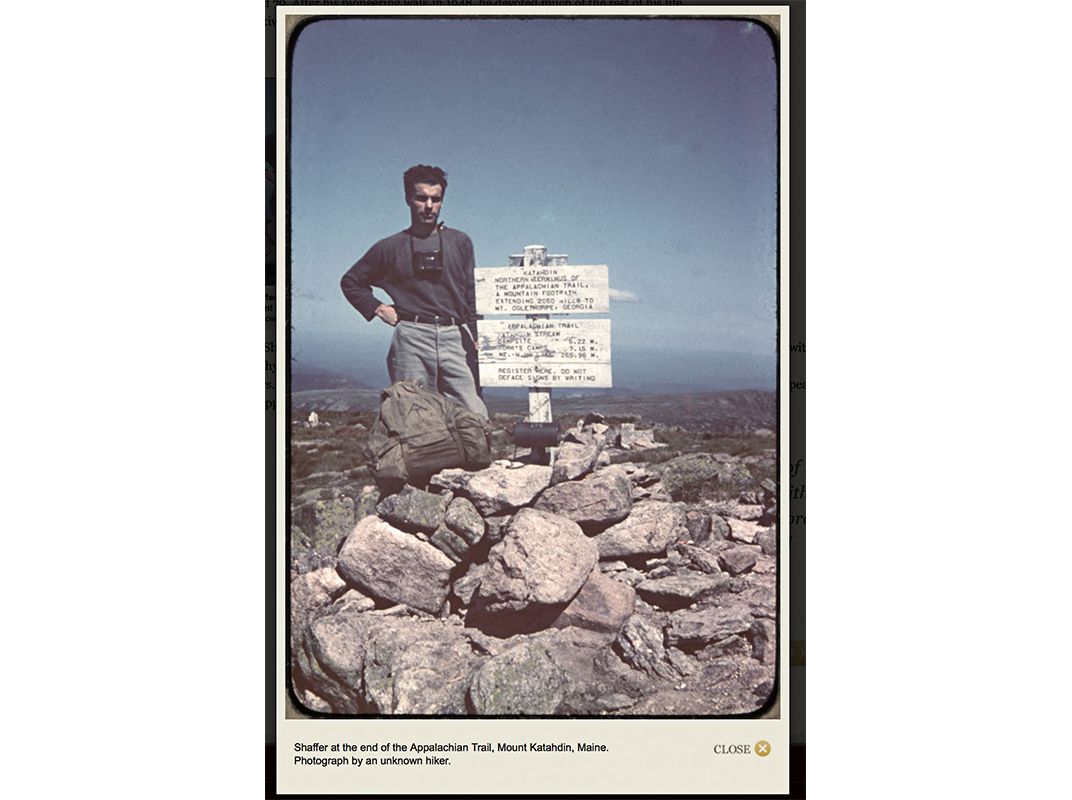

Shaffer was a World War II veteran, who, in 1948, became the first person to walk the entire Appalachian Trail. He was so picky about gear that he ditched his own cumbersome tent, sleeping in a poncho for months instead. He was particularly enamored of his Russell Moccasin Company “Birdshooter” boots, which bore him all the way from Georgia to Maine. (By contrast, modern through hikers may chew through two or three pairs of newfangled Gortex contraptions.) He paused often to sew, grease and patch his footwear, and twice had the soles replaced at shops along the route.

The boots today are still redolent of 2,000 miles of toil. (Shaffer frequently went without socks.) “They are smelly,” confirms Jane Rogers, an associate curator at the National Museum of American History, where these battered relics reside. “Those cabinets are opened as little as possible.”

Perhaps the most evocative artifact from Shaffer’s journey, though, is an item not essential for his survival: a rain-stained and rusted six-ring notebook. “He called it his little black book,” says David Donaldson, author of the Shaffer biography A Grip on the Mane of Life. (Shaffer died in 2002, after also becoming the oldest person to hike the whole trail, at age 79, in 1998.) “The fact that he was carrying those extra five or six ounces showed how important it was to him.”

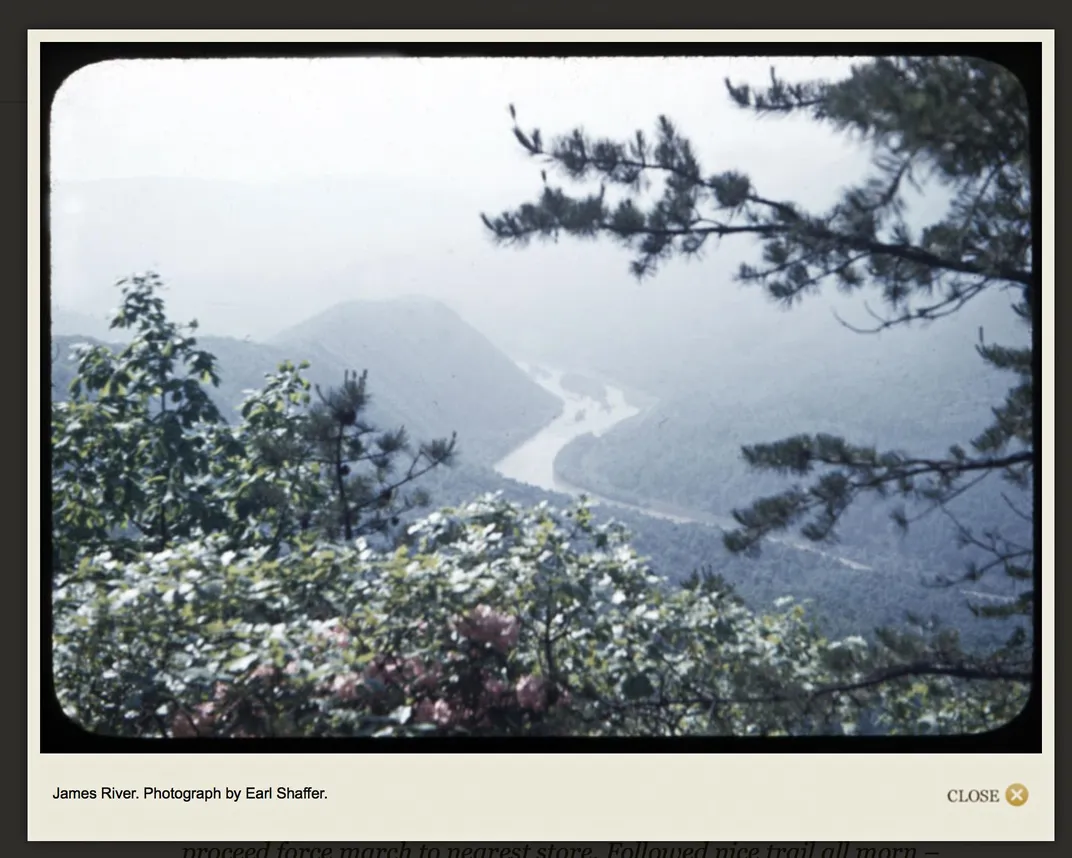

First and foremost, Shaffer, who was 29 at the time, used the journal as a log to prove that he had completed his historic hike. The Appalachian Trail, which marks its 80th anniversary this summer, was then a new and rather exotic amenity. Some outdoorsmen said that it could never be traversed in a single journey.

But the journal is about more than mere bragging rights. “I’m not sure why he needed to write so much,” says archivist Cathy Keen of the National Museum of American History. Perhaps Shaffer tried to stave off the loneliness of the trail, which was not the well-trafficked corridor that it is today. (About 1,000 trekkers through-hike each year, and two to three million walk portions of the trail annually.) Shaffer also sang to himself a lot, loudly and, in his opinion, poorly. An amateur poet, Shaffer may have been attempting to hone his craft: He jots a few rather forced and flowery nature poems in the notebook’s pages.

The most arresting entries—the entire journal is accessible online—are Shaffer’s casual notes about the voices of wildcats and whippoorwills, and other impressions, lyrical and stark. “Marsh Pipers peeped in Pond during night and I could blow my breath to the ceiling in morn,” he wrote. And, another day: “Cooked chow on willpower.” Shaffer’s stripped-down style telegraphs his raw exhaustion, and the journal’s sudden, charming transitions give the reader a palpable sense of the twists and turns of the trail: One minute Shaffer is walking by starlight, the next he’s washing his underwear. He is harried by copperheads and Girl Scouts, and a raccoon that wants to lick his frying pan. Indeed, Shaffer didn’t know it, but he was pioneering a whole new American genre, the Appalachian Trail journal, popular on online hiking sites and perhaps best known from Bill Bryson’s A Walk in the Woods.

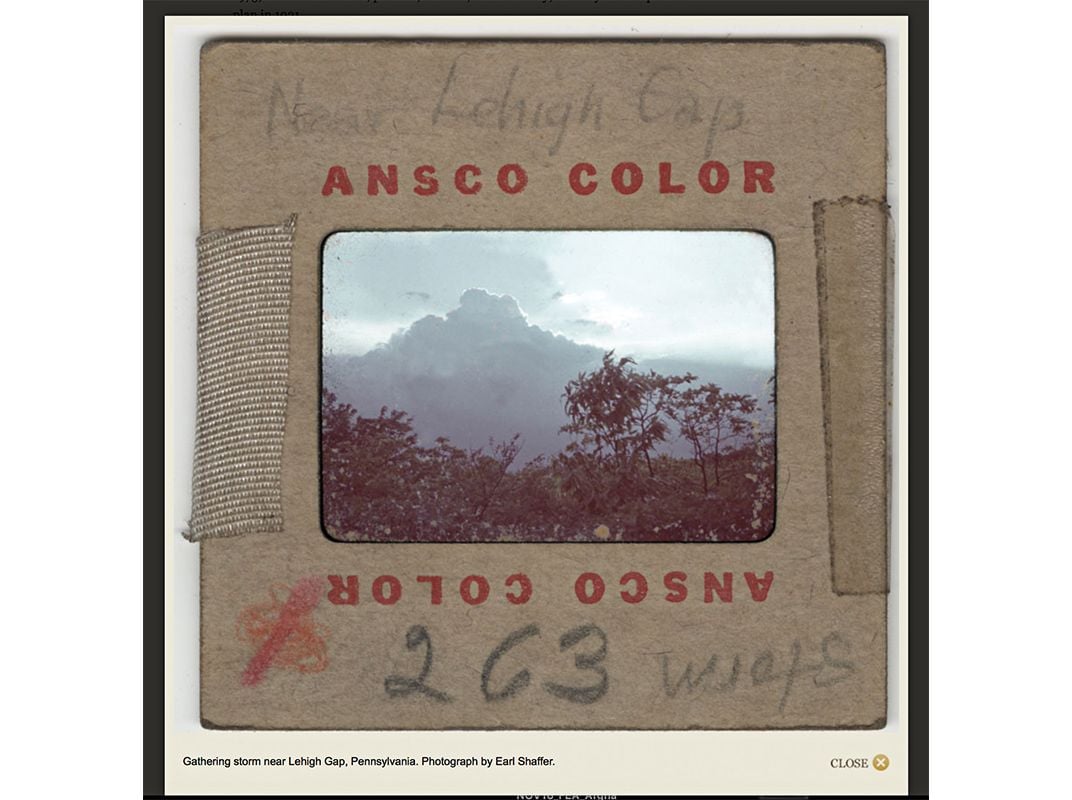

There are hints of other burdens that he bore, the sort that can’t be weighed in ounces. After serving in the South Pacific for four years, Shaffer claimed that he set out on the trail to “walk the war out of my system.” Yet he sees war everywhere along the bucolic path, which, after all, passes by Antietam and other blood-soaked terrain. He makes note of military memorials and meets fellow veterans, as well as a farmer whose son “was psycho from [the] army.” Nature itself has martial aspects: A mother grouse explodes from the underbrush like “an A-bomb,” and even the clouds resemble aircraft carriers.

Twice Shaffer mentions Walter, a childhood friend who died on Iwo Jima. They had planned to hike the trail together.

“Passing down long grassy inclined ridge, came to lonely grave of soldier,” Shaffer writes one day. What soldier? Which war? Shaffer doesn’t linger or elaborate. And on the next page, he gets his boots resoled.

See Earl Shaffer's Appalachian Trail Hike Diary.

Walking with Spring

A Walk in the Woods: Rediscovering America on the Appalachian Trail