A World Of His Own: The Art of James Castle

Born profoundly deaf, the self-taught artist’s body of work depicts his unique relationship to the world around him

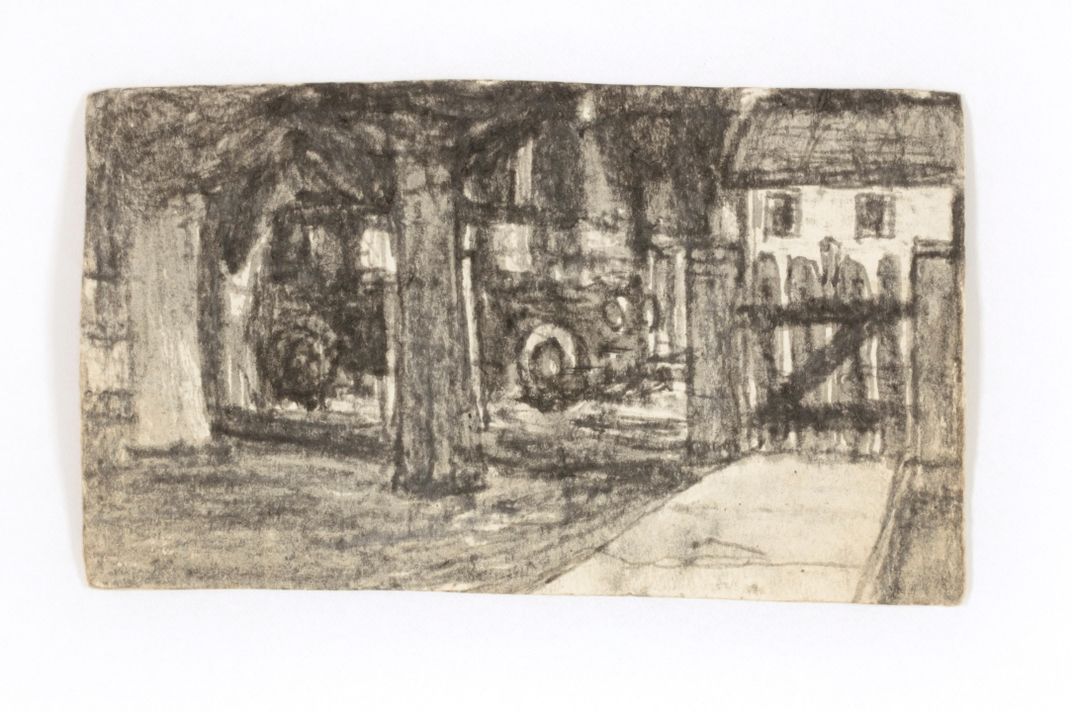

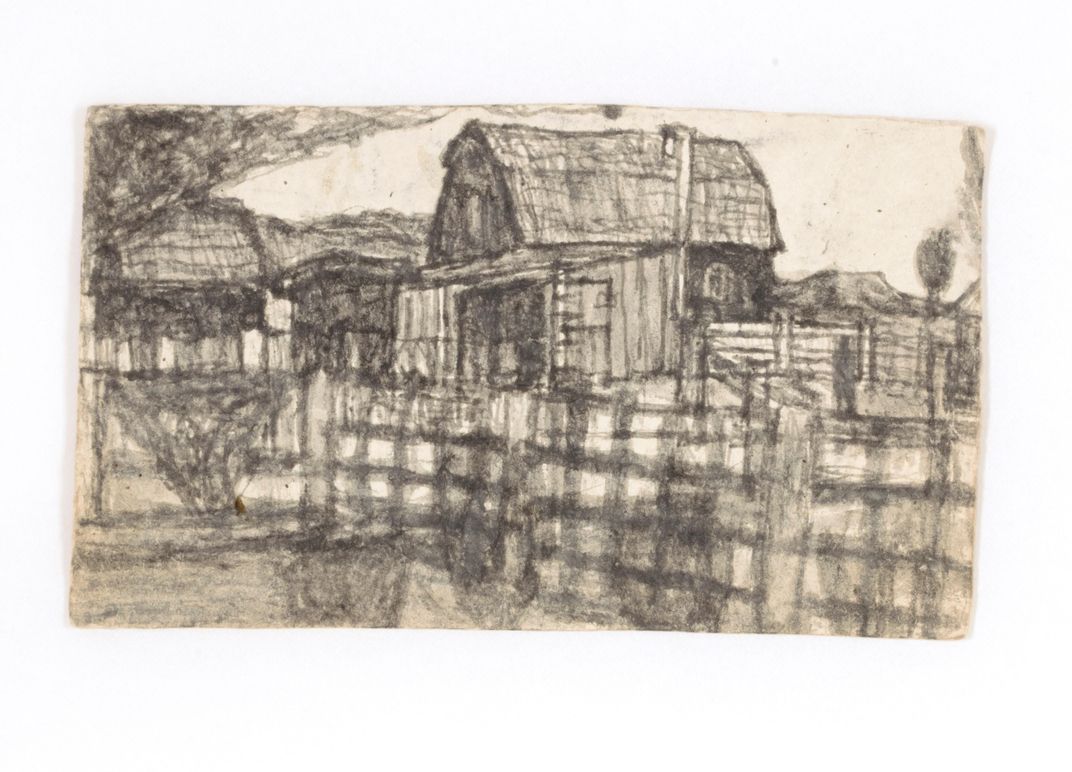

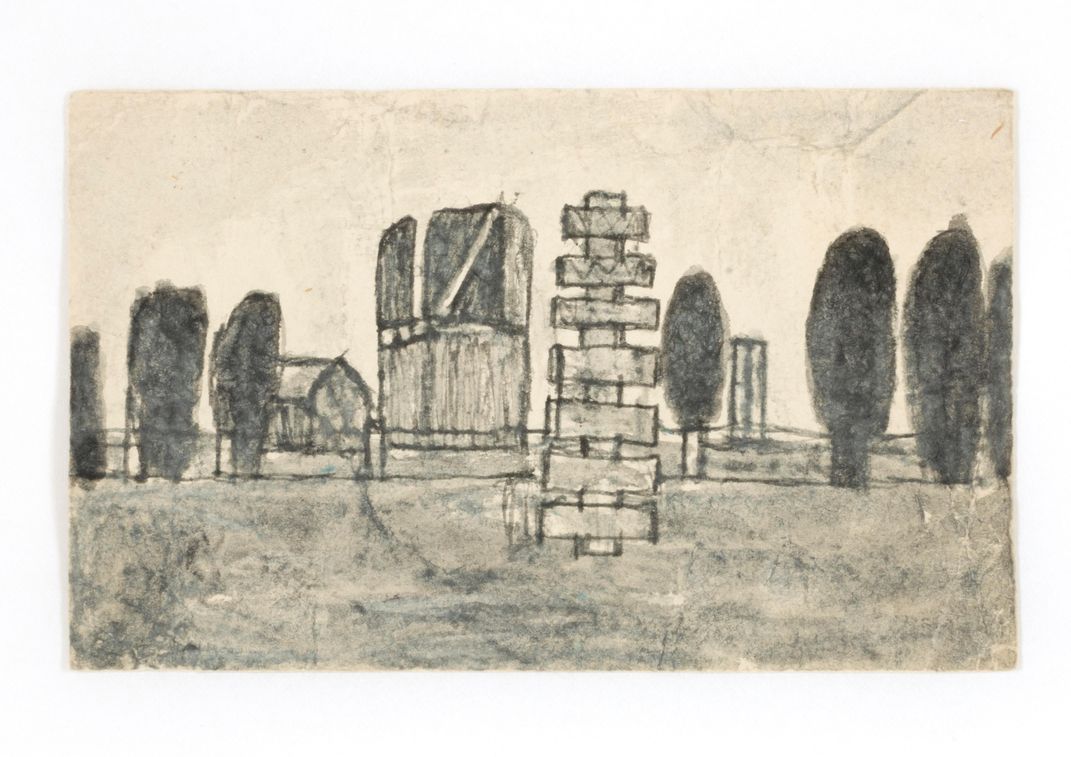

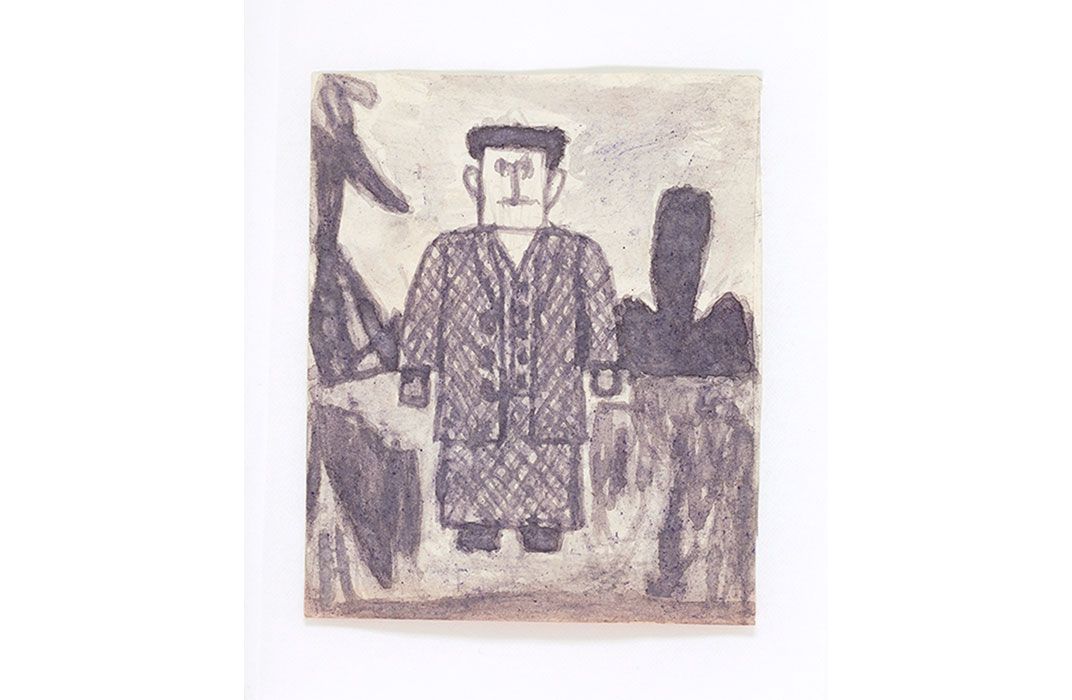

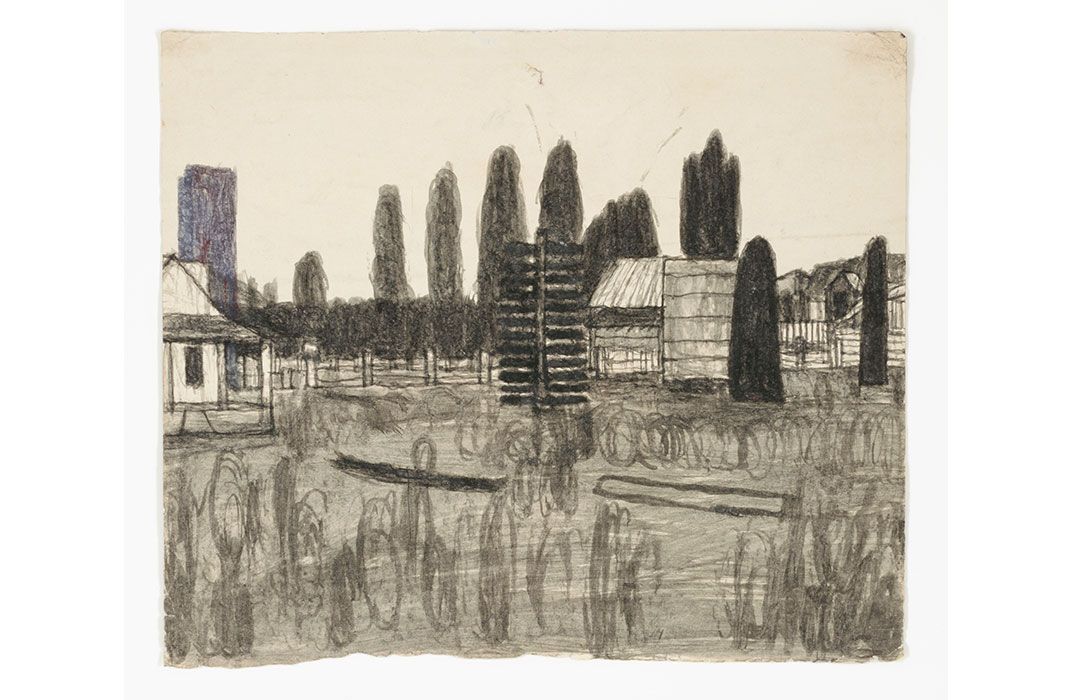

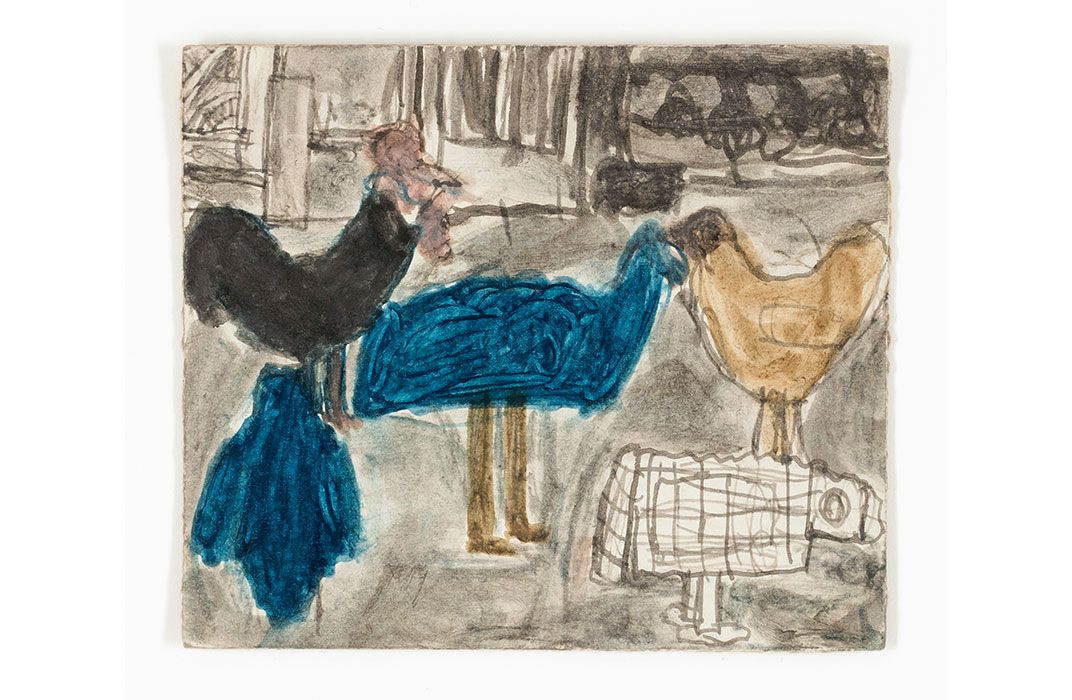

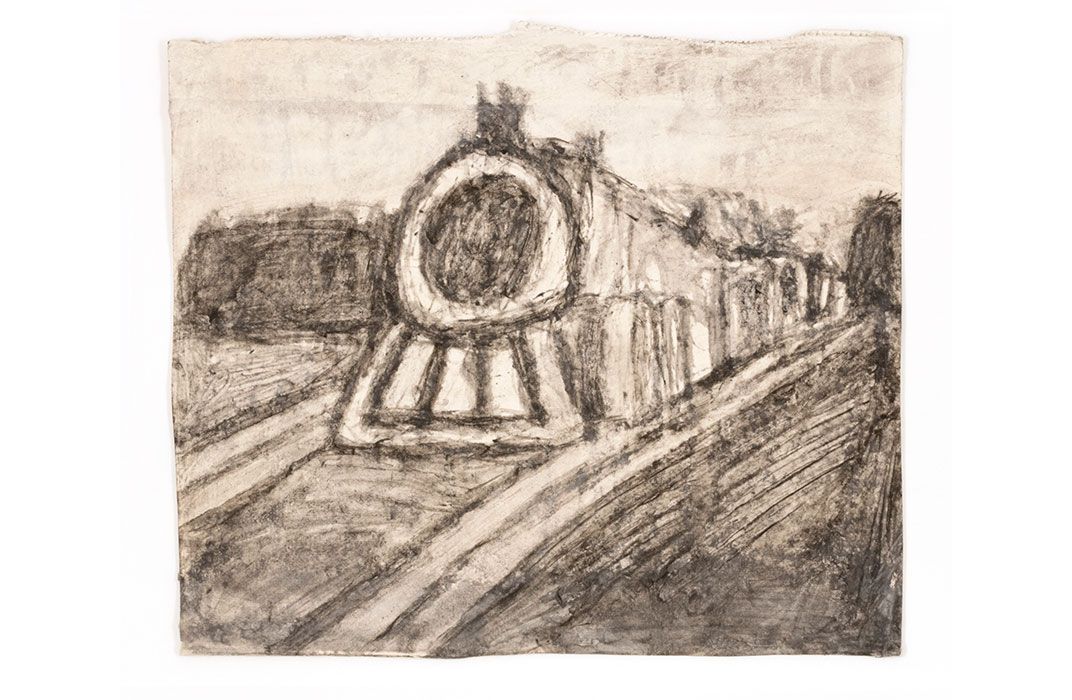

The world as seen through the eye of the self-taught artist James Castle, one that is drawn in black and white lines made from the simple mixing of soot and saliva, is a unique one. Not just for its place in time—in the waning years of the early 20th century when the Western frontier was being settled—but for the circumstances surrounding the artist's early life and his prodigious work output. "He stored his art in many locations around the family property—in barns, sheds, attics, walls," says curator Nicholas Bell, co-author of the show's catalog Untitled: The Art of James Castle. "But I wouldn't say he was trying to hide it from anyone, per se. Before he died he communicated through gestures to his family where all of his art was stored so they could take care of it."

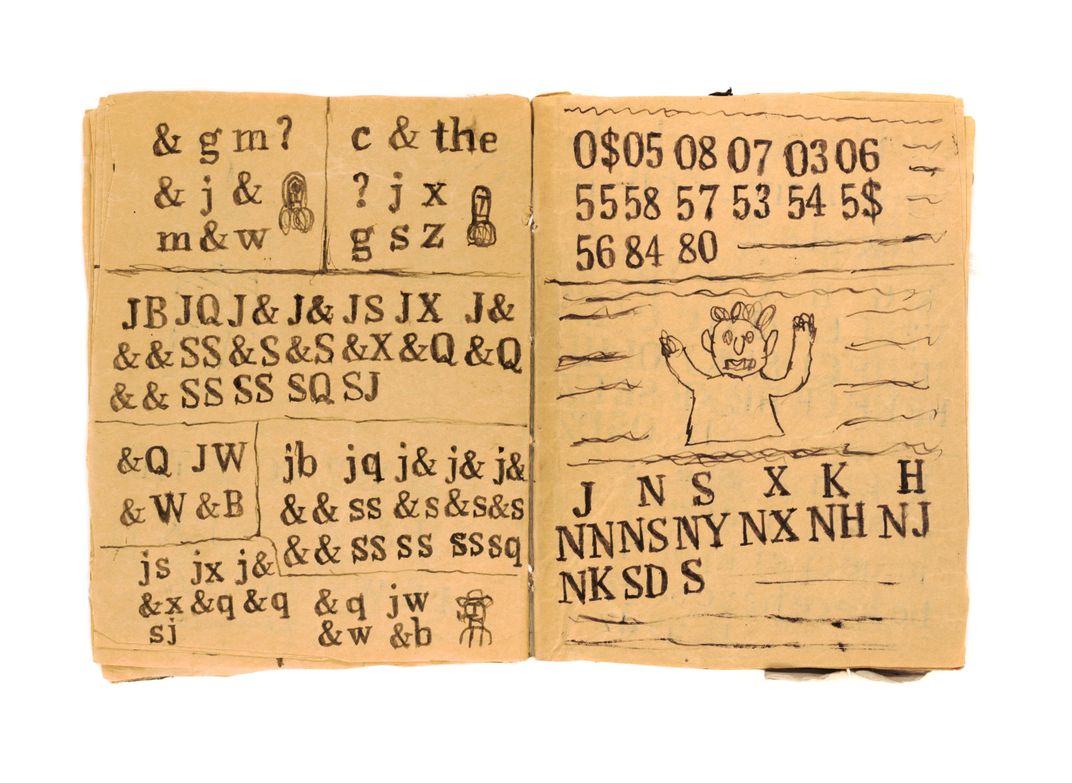

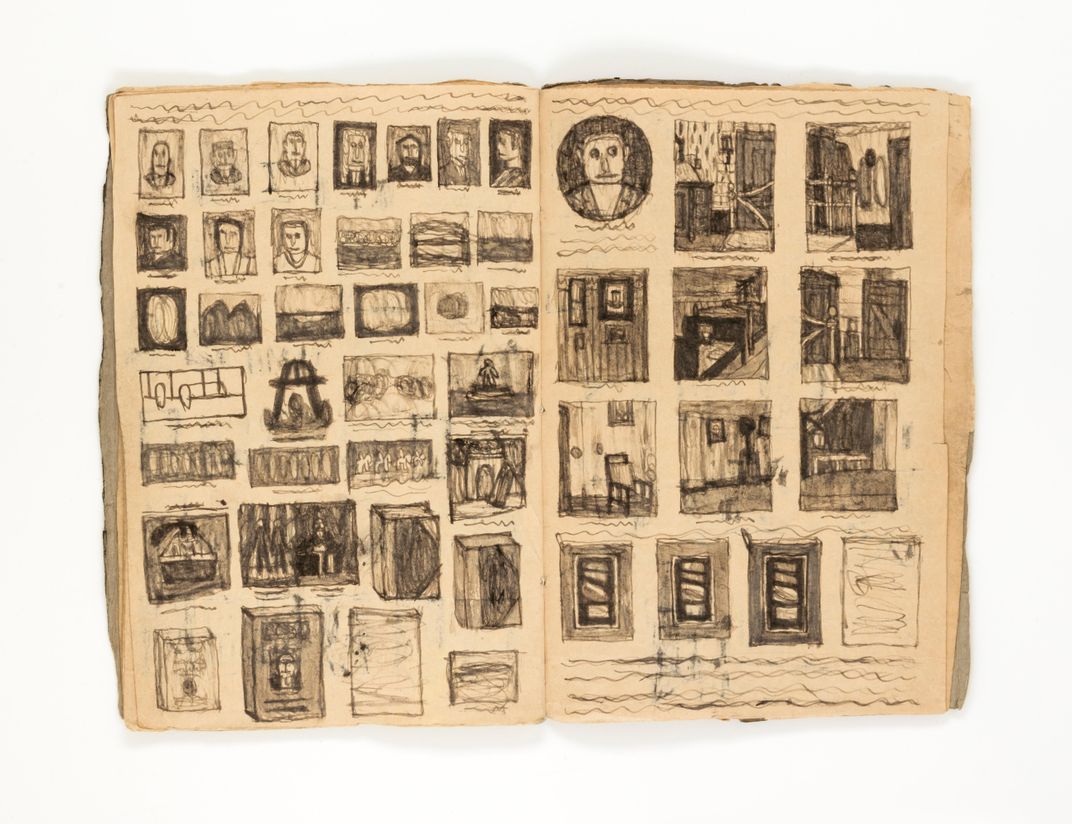

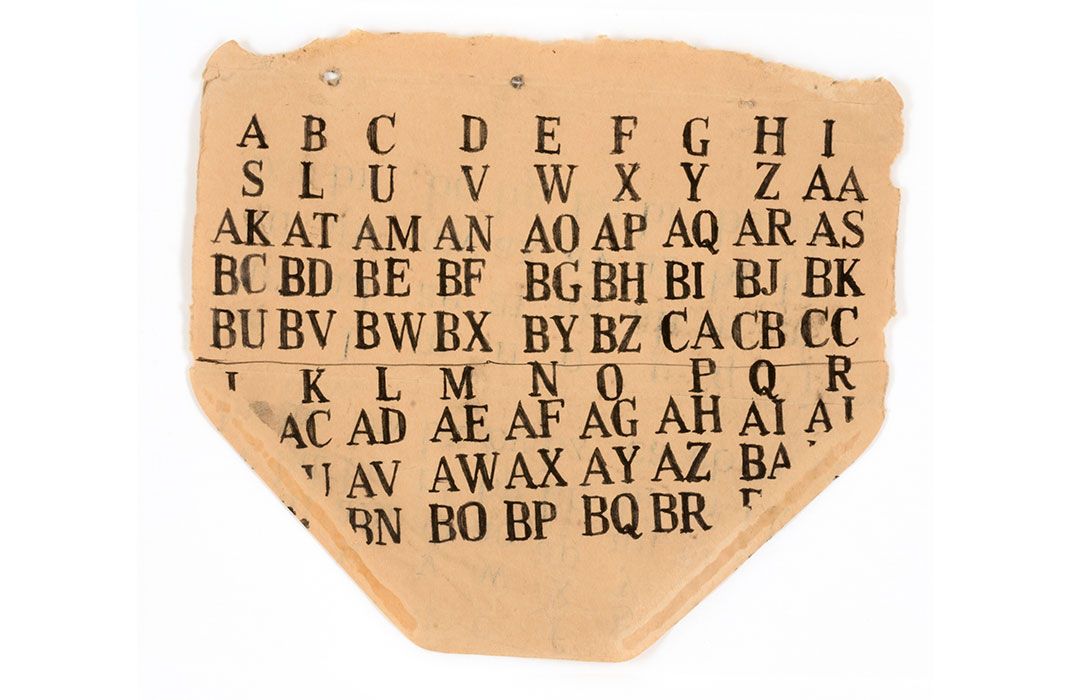

Born profoundly deaf, Castle never learned to read, write or communicate in any traditional sense. Yet for nearly 70 years, Castle interacted with the world around him communicating through his art, creating drawings, books and constructions that reflected his individual reality. "James Castle is his own art history," explained John Ollman, owner of the Fleisher/Ollman Gallery in the 2008 documentary James Castle: Portrait of an Artist. "He's using himself as his own reference material."

Through February 1, 2015, Castle's work will be on display at the Smithsonian American Art Museum in "Untitled: The Art of James Castle," an exhibition that celebrates a 2013 acquisition of 54 Castle pieces, making the museum home to one of the largest collections of the artist's works. "James Castle's drawings and paintings confirm that art offers a fundamental way to know ourselves," said the museum's director Betsy Broun in a statement. "He worked for decades in the rural west, surrounded by family but with little experience beyond his community and with no formal art training. But his discerning eye found subjects all around, creating an extended portrait of his world."

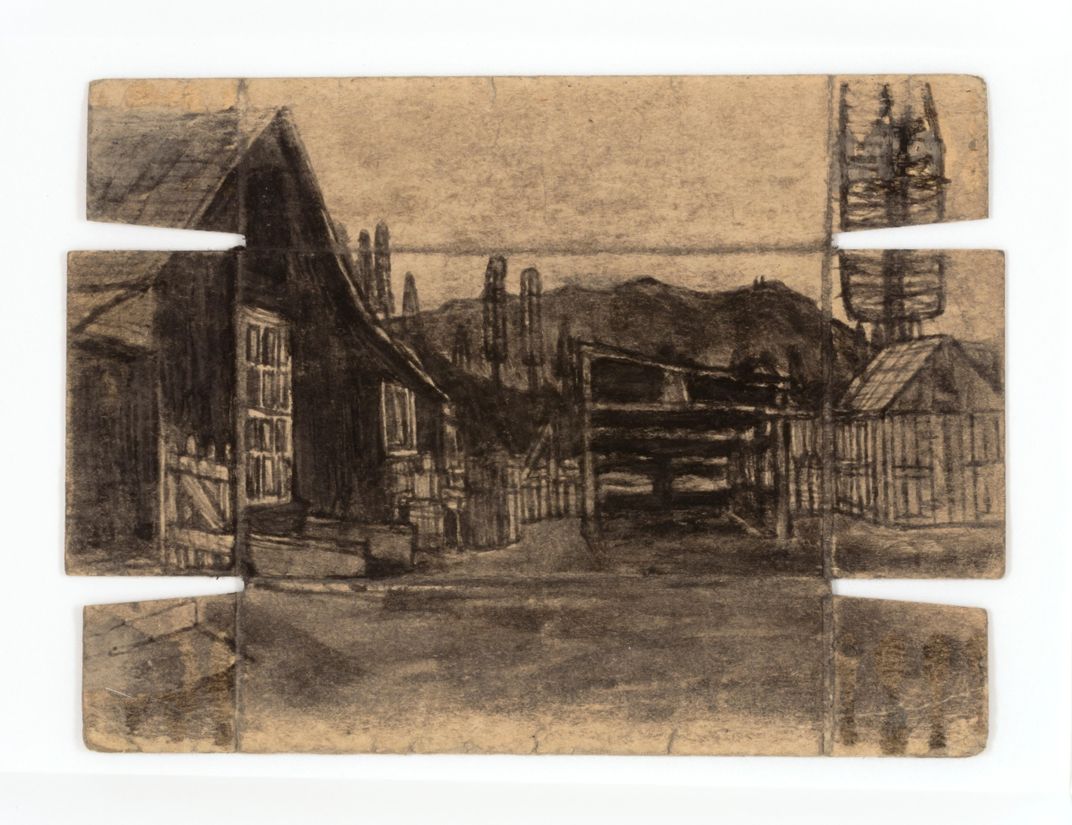

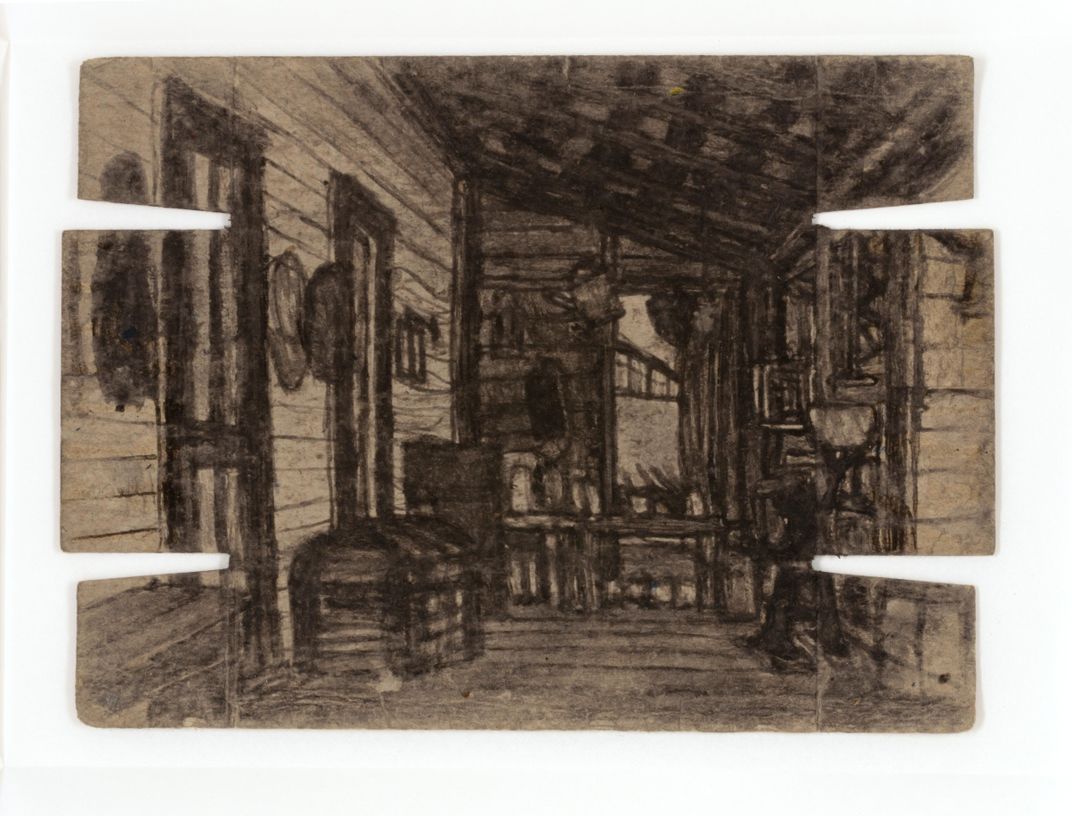

Born two months premature on September 25, 1899, to rural postmasters who ran a general store out of the living room of their home in Garden Valley, Idaho, Castle grew up in the shrinking world of the pioneer frontier. From the ages of 10 to 15, he attended the Gooding School for the Deaf and Blind, where he was taught an oral method of communication—not sign language. And with no formal art training he worked virtually unknown for the first 40 years of his life before the art world discovered him. But by 1964, Castle was being described as the "most important primitive since Grandma Moses," by the director of the Portland Art Museum, whose style "reminds us of Van Gogh."

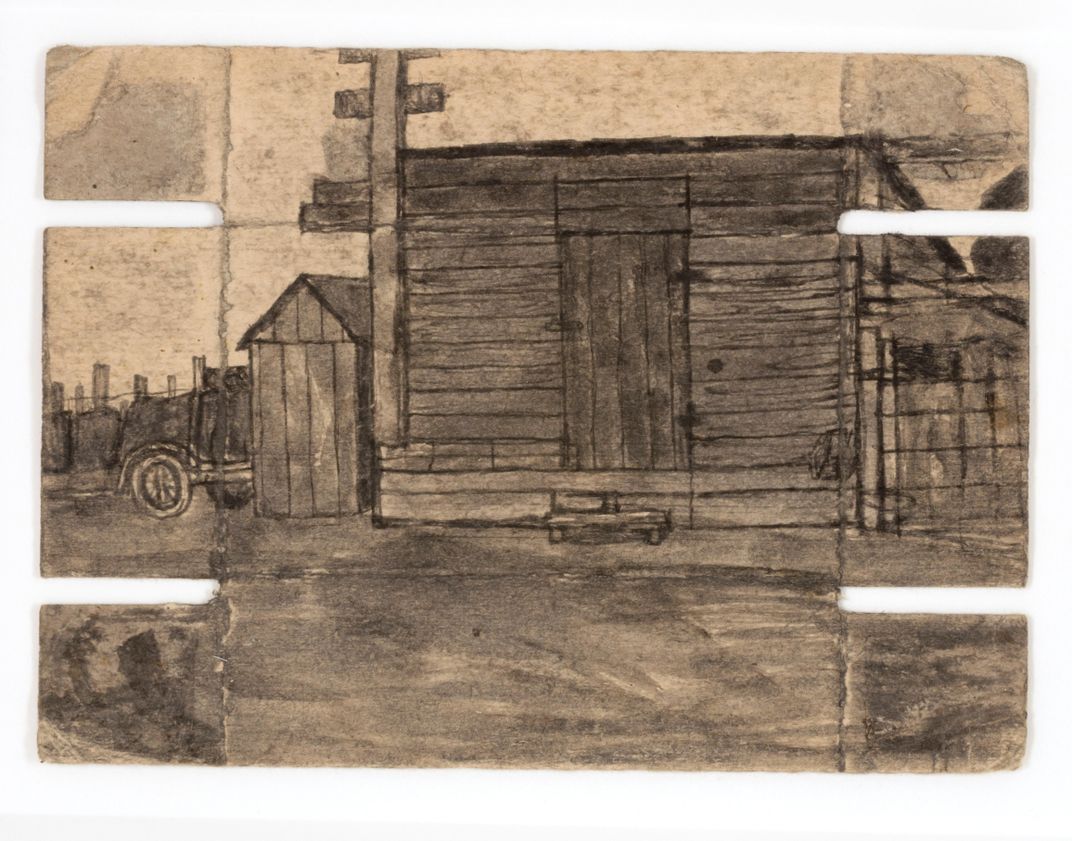

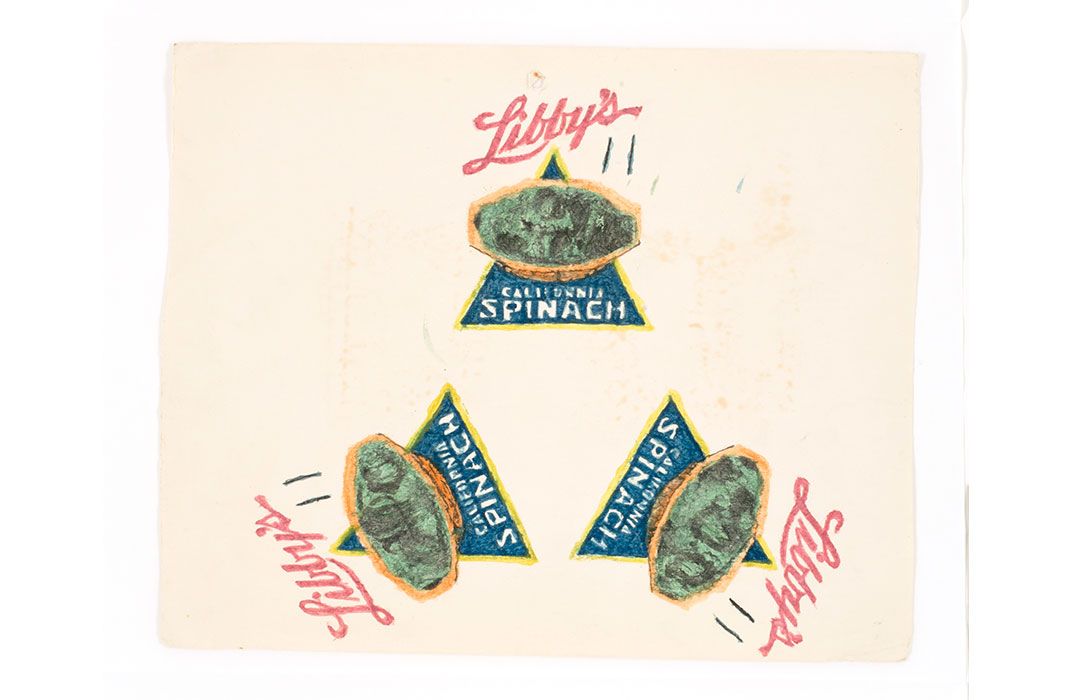

Castle created his work using found objects: paper from his parent's post office, cardboard from matchboxes, soot from the wood stove mixed with saliva to create a kind of charcoal ink. He was profoundly productive, crafting works at a near constant rate for almost his entire life. Many of his drawings are on the back of used envelopes, or used pieces of paper or even on the interior of an unfolded matchbox (in the slideshow above, the images with slots in the sides are done on such a medium). His works largely reflects the rural landscape that surrounded him for his entire life: after leaving Garden Valley as a young man in 1924 (and moving first to Star, Idaho and then to Boise), his illustrations often recalled the farmyard of his Garden Valley home. Castle's works are all undated, but any surviving artwork is thought to date from after 1931, when he moved to Boise, meaning that landscapes which recall his boyhood homes must have all been painted from memory. Many of Castle's works also explore the idea of text, which seemed to fascinate Castle in spite of his reputed illiteracy.

"At once inviting and inscrutable, Castle's art gives us access to a world navigated without language, though not the key to unlock it," says Bell. "Ultimately, grappling with these drawings reveals the limits of our understanding as well as one artist's extraordinary vision of the ordinary."

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/natasha-geiling-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/natasha-geiling-240.jpg)