This Artist Deconstructed His Love and Fascination for Calvin and Hobbes

Tony Lewis finds a new way of writing poetry, through artistry, and his assemblage of cut-up dialog balloons from Bill Watterson’s much-loved comic strip

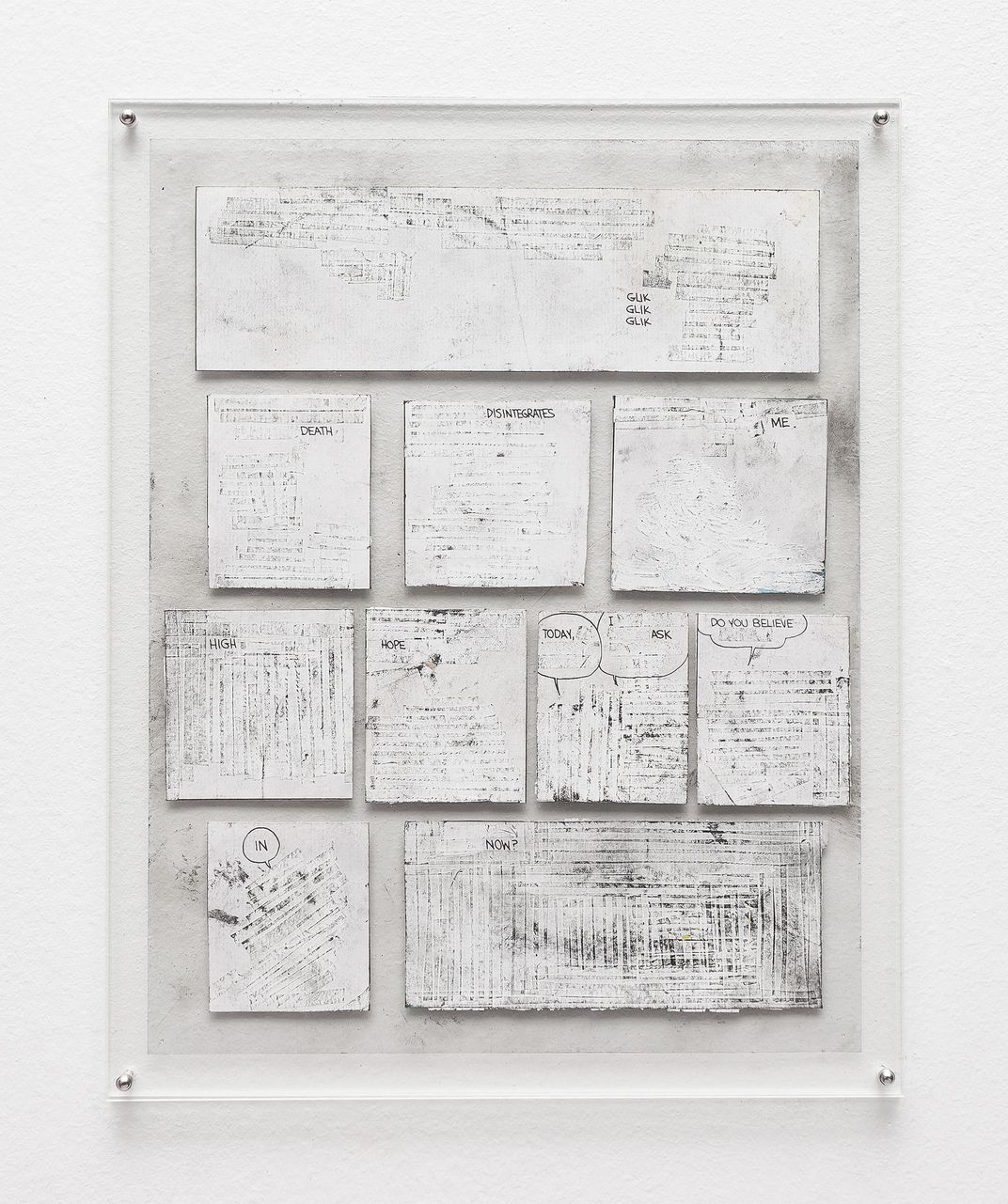

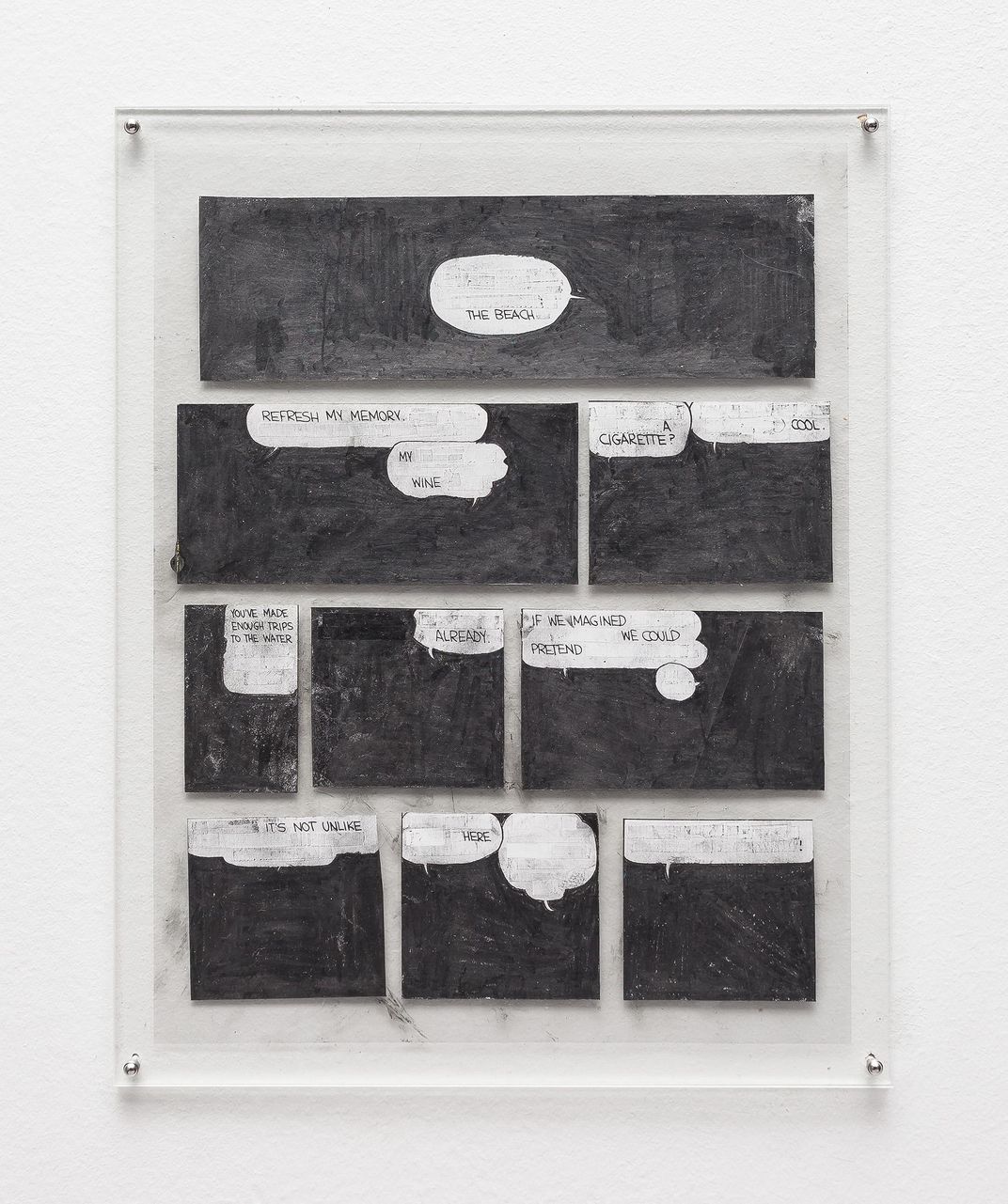

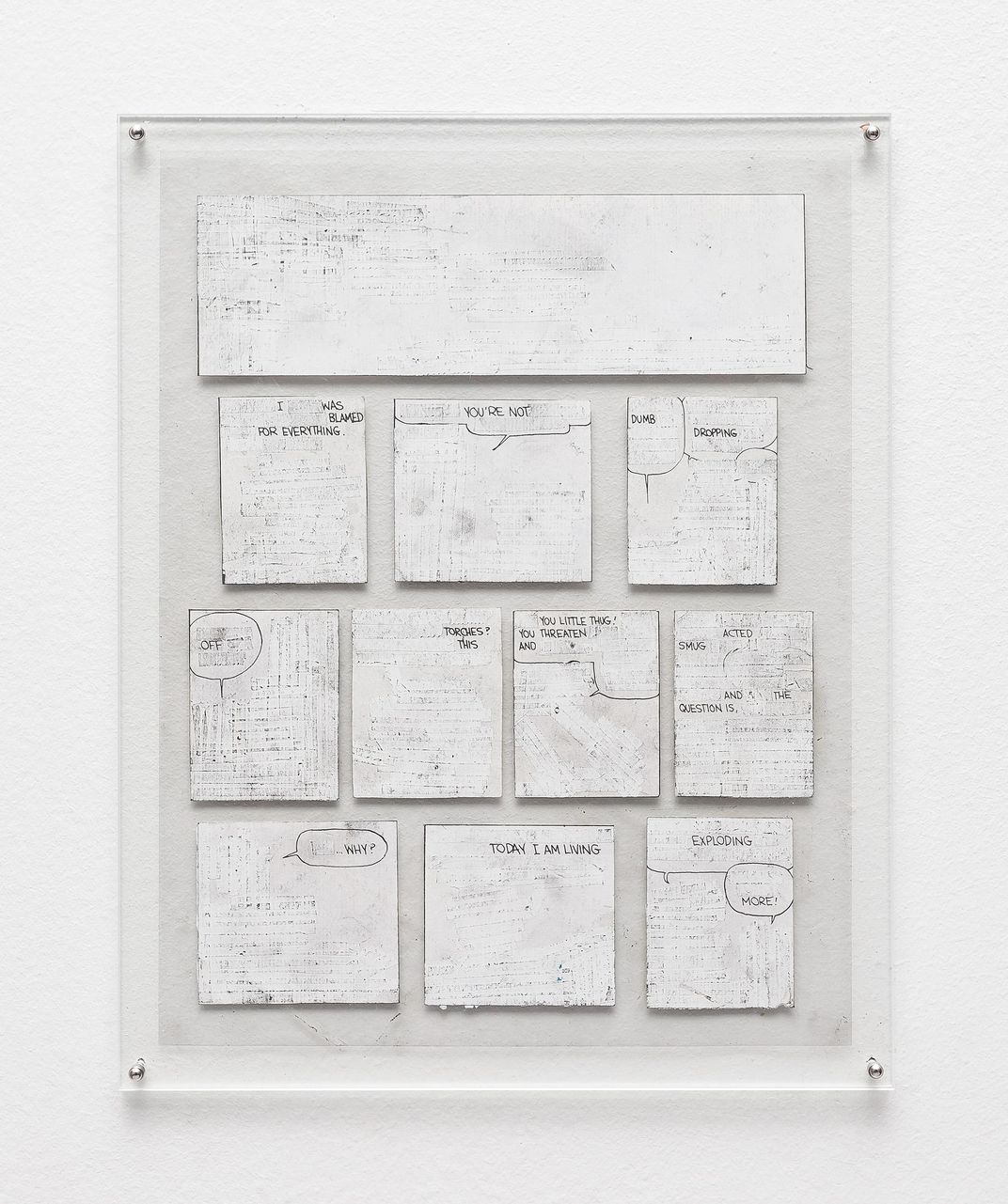

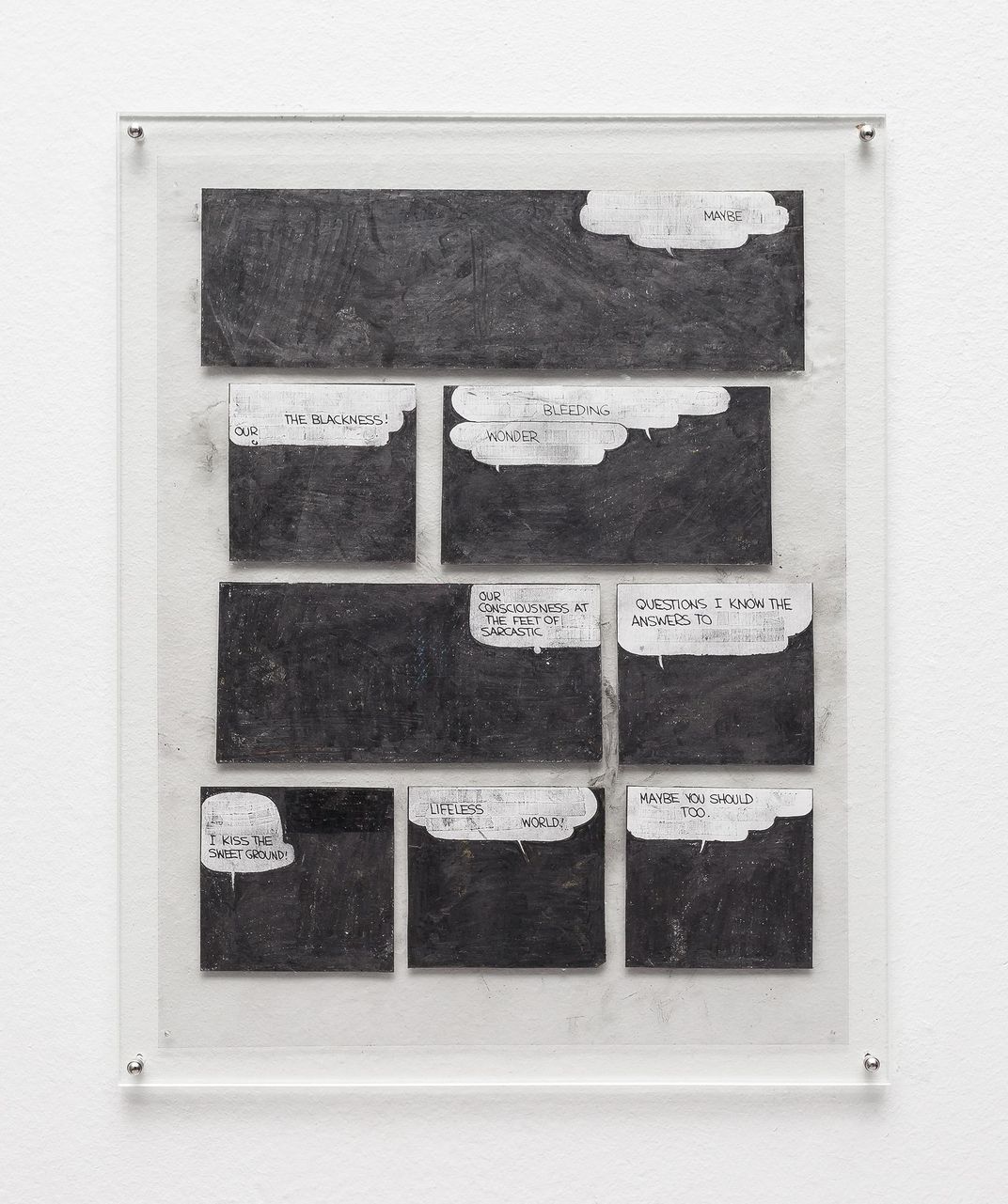

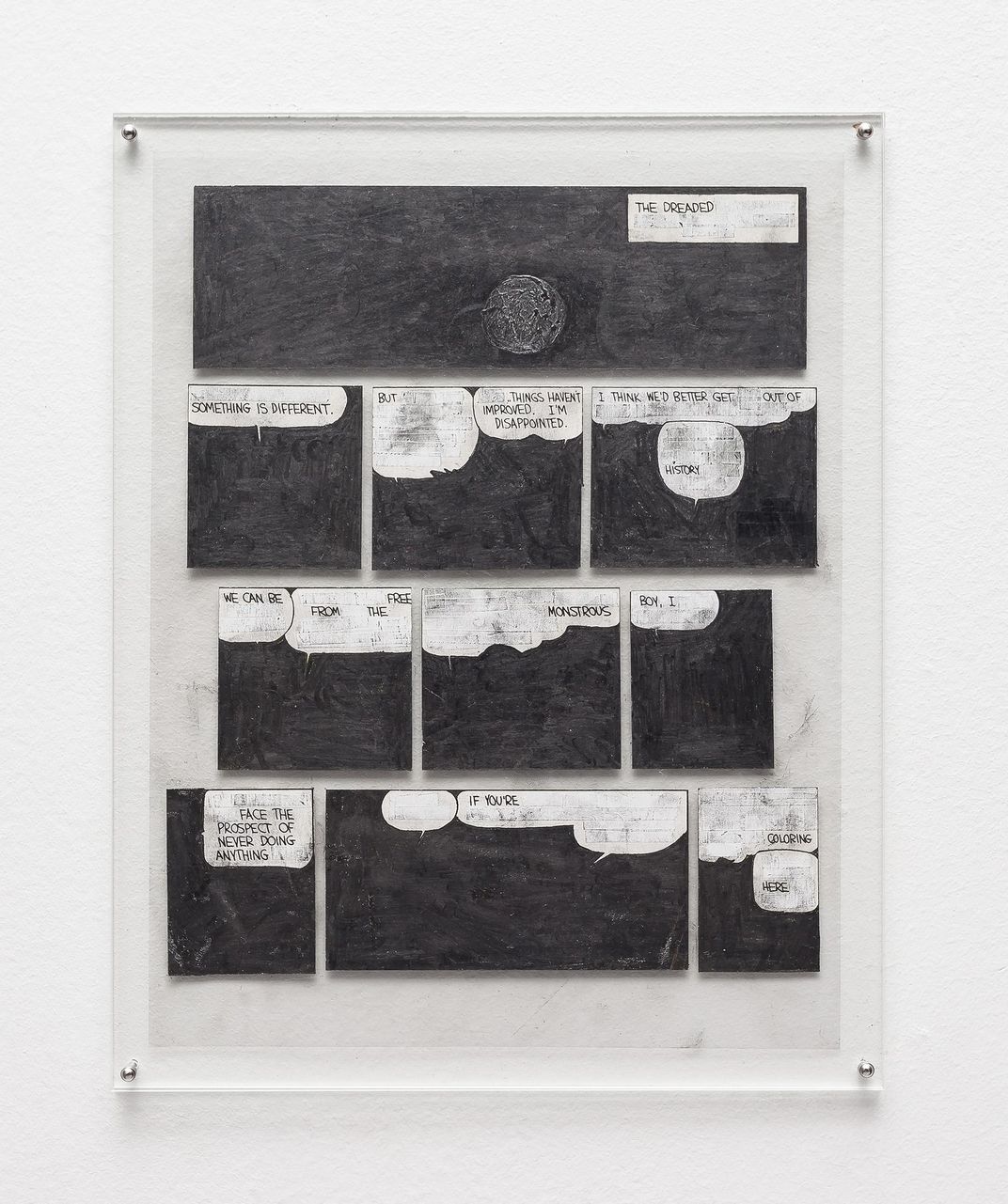

Art is not always the creation of something. Sometimes, it is the act of elimination. Robert Rauschenberg famously erased a Willem de Kooning drawing for a notorious 1953 work. Several works by the graffiti artist Banksy have been painted over, accidentally or purposely, over the past decade. And in a new show at the Smithsonian’s Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, "Tony Lewis: Anthology 2014-2016," what looks to be dozens of comic strips of Calvin and Hobbes are drawn over or whited-out, leaving seemingly random words and dialog balloons.

Chicago artist Tony Lewis has long been interested in modes of drawing and language, but in this set of work, he’s obscured all but the words that spoke to him, cut out the individual frames, shuffled them, and reassembled them into a kind of comic strip-derived cut-out poetry—pieces that he also recopied in a newly published book of free verse.

For Lewis, it’s a way to pay homage to a formative childhood influence even as he inserts his own ideas into a new recontextualized narrative. The pieces, he says as he stands amid his work on opening day, “had been happening sort of under the radar, in a private setting, in a different studio space than a lot of the larger work. It’s also been kept under the wraps as a full project.”

While some of the pieces have popped up in exhibitions, the Hirshhorn show, his D.C. debut, is the first time they’ve been displayed together as a group—alongside a book of poetry derived from the pieces, published in a limited printing.

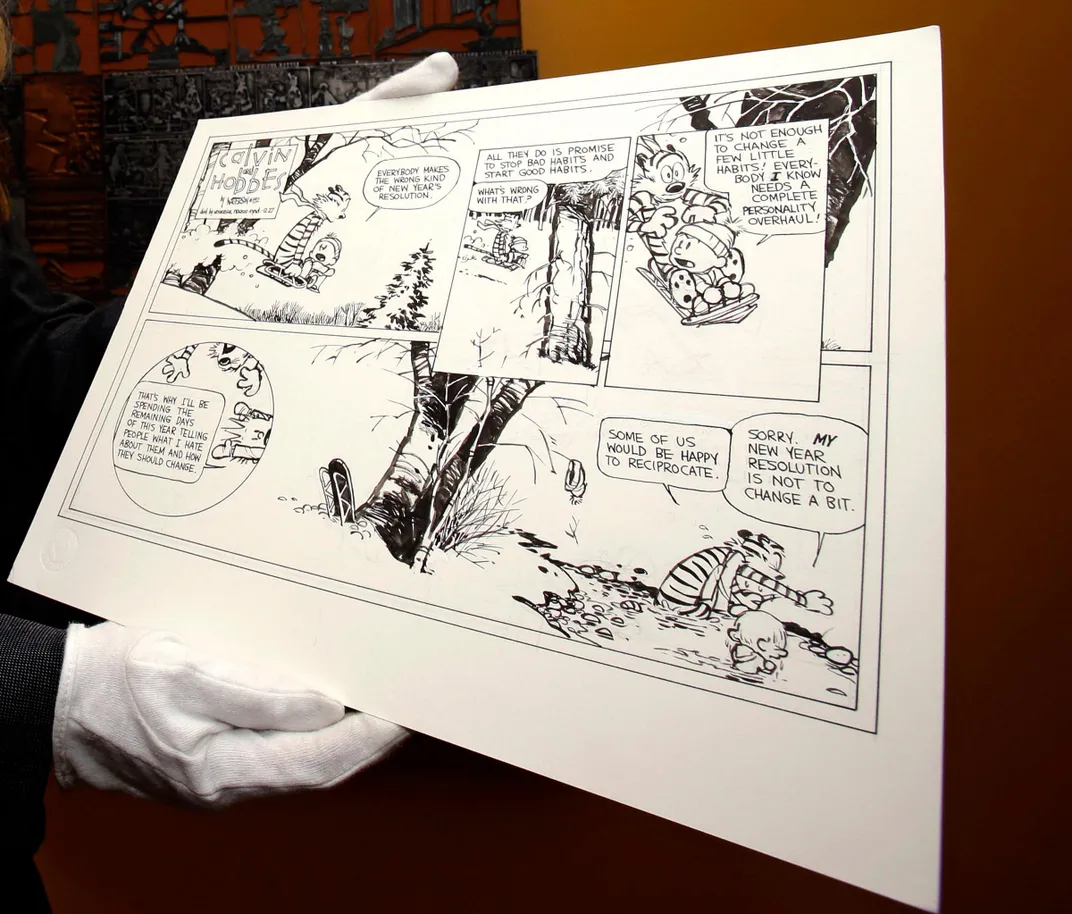

That’s because, in addition to being a drawing project, Anthology is also a writing exercise. It began with Lewis’ childhood fascination with Calvin and Hobbes, the influential and popular comic strip by Bill Watterson about a boy and his stuffed tiger that ran in thousands of newspapers worldwide during its run from 1985-1995. Its 11 anthologies became touchstones for millions of readers, Lewis included.

“It’s my favorite comic strip since I was a kid,” Lewis says. “Calvin and Hobbes was the first time I saw humor, the first time I saw art, the first time I saw ability to draw, the first time I saw narrative—all at once. And that was super-captivating.”

It also had running philosophical arguments that have found their way into Lewis’ prose as well, despite cutting and mixing up the dialog.

He began Anthology because he had duplicate copies of Calvin and Hobbes books in his studio. “I’ve bought tons and tons of secondhand copies of the same books. I did that initially because, if I lost one or damaged one, I’d have the other one,” he says.

“Whenever I bring anything into my studio it becomes a victim of the space because it’s very dirty, it’s very intense,” Lewis says. “It’s an art studio—there’s a lot going on. So the books became unusable as books. Then I had to figure out something to do with them. The idea of making these drawings came natural.” So as he worked on much bigger pieces at Art Basel and the Whitney Biennial, he kept working on this smaller set of works quietly in another studio.

Using correction fluid to white out the drawings, or graphite to obscure it in black, he had stacks of individual panels with words on them left from the dialog balloons.

“Sometimes you put them next to each other and you’re lucky and it makes sense,” he says. “Or it says something funny, you keep it. Or you blow them all away and they’d be gone. And then I’d try to recreate it and I wouldn’t be able to. It’s sort of like losing your thought in the middle of writing.”

But in the middle of combining words and phrases, in the manner of poets Tristan Tzara and William Burroughs (or rockers who borrowed the same techniques, from David Bowie to Thom Yorke), themes would appear.

“You start to see, just like this,” Lewis says, turning to one piece and reading it, “‘Childhood is forever . . . and I hate when it’s not.’ To me that’s kind of a crazy perplexing kind of phrase and I wanted to stick with that.”

Then he built the rest of the works, which had the same number of panels and frames as a typical Sunday comic—though these are minus the images, the original words or even the same story lines. “I like the idea that every step of it can be something that people can access or deal with or understand,” Lewis says, referring to the familiarity of the comic strip format. “You can appreciate the show as evidence of a larger writing process that obviously is not perfect, and is at the beginning of working itself out.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/ab/0f/ab0fedd9-04bd-4e45-ae35-c6ac400ba6c6/tonylewis.jpg)

“That’s the mind-opening quality of this work,” says exhibition curator Betsy Johnson, “realizing that there are different ways to write. I think for kids, who see this and think, this is art: appropriation and erasure, it’s not always about pure creation. It’s about drawing things from outside yourself and putting it together in a new pathway. And when people can see that, it can be earth-shattering.”

The 34 works are a perfect fit with a continuing exhibition from the permanent Hirshhorn collection, “What Absence is Made Of” that surrounds it, demonstrating a similar approach of reduction and erasure as art. Nearby, too, is “Mark Bradford: Pickett’s Charge,” the work by another contemporary African-American artist, Mark Bradford, who similarly re-appropriated a source material—the Gettysburg cyclorama—and reduced and added a lot of texture to it to become something new.

“Which is cool,” Lewis says. “I have a lot of respect for Mark Bradford.”

Though Lewis and Watterson both lived around Cleveland, the artist’s appropriation of the cartoonist’s strip meant he could insert the one thing that was missing from the strip that otherwise seemed to have everything—himself.

“They deal with a way to insert myself, my biography and my life into that storyline, because there is an absence of who I am in that, in all the greatness that is Calvin and Hobbes,” Lewis says of his project.

“Some of these poems talk about things Calvin wouldn’t be caught dead saying,” he says. “I think it’s important to talk about things that are happening now or other aspects of life, that have nothing to do with the perceived narrative that exist in the original comic.”

"Tony Lewis: Anthology 2014-2016" continues through May 28 at the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden in Washington, D.C.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/RogerCatlin_thumbnail.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/RogerCatlin_thumbnail.png)