An all-white raven named Yéil is a trickster in many oral traditions originating on the Northwest Pacific Coast. In a bold plot to transform life on Earth, the white bird wants to shine light from the sun and the moon and the stars on the world. To do so, raven must transform again and again.

Yéil learns of a nobleman who lives at the head of a river. While the man’s great wealth is appealing, the bird is more interested in his carved boxes that contain the sun, moon and stars. After deciding that he wants to go to the clan house to release this light for other creatures to see, the raven embarks on a path of shapeshifting and trickery. He knows that he can’t reach the clan house in his bird form, so he first becomes a speck of dirt. Then, he becomes a piece of hemlock floating in the river. This transformation works—the nobleman’s daughter scoops him up in a ladle and swallows him. His next form is that of a human child, ultimately born by the daughter.

Yéil grows up well-loved in the clan house, and the nobleman showers him with gifts and affection. However, those treasured boxes are never far from the raven’s mind. When he finally decides he is ready to return to his bird form and leave, he breaks the boxes. This sets the light free.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/ca/33/ca33dfa5-b5b4-4638-80fa-d718284bf96a/preston_singletary_011.jpg)

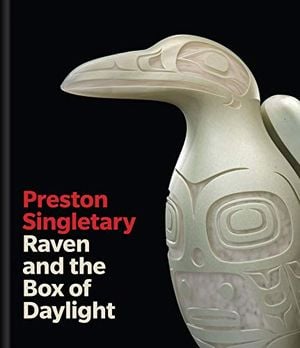

Preston Singletary: Raven and the Box of Daylight

Preston Singletary's art creates a unique theatrical atmosphere, in which the pieces follow and enhance a narrative. This book places Singletary's work within the wider histories of both glass art and native arts traditions―especially the art of spoken-word storytelling.

Preston Singletary, a renowned Tlingit American glass artist, first visited the narrative with his handblown sculpture Raven Steals the Sun, which joined the collections of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of the American Indian when it opened in 2004. Now, nearly two decades later, his raven is back as part of the immersive “Preston Singletary: Raven and the Box of Daylight” exhibition. Singletary created more than 60 glassworks to illustrate the story, pairing them thoughtfully with music and projections.

Singletary first conceived of the traveling exhibition after meeting the Tlingit historian and storyteller Walter Porter in 2004, at the museum’s opening. Porter, says Singletary, viewed the raven stories through the lens of a mythologist. He drew parallels to psychology and other religions, captivating Singletary with the “universality” of the raven. “I really wanted to work with him,” Singletary says. “He was willing to pass on his knowledge to me so that I could share it more widely.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/43/e3/43e320cd-e58d-4710-a02d-06513835b863/singletarysalmon_46_hr.jpg)

This influential encounter came two decades after Singletary started his glass journey at Seattle’s Glass Eye Studio, where a friend had helped him get a job. He went on to study at the Pilchuck Glass School, where his growing relationship with the medium allowed him to “reinvent” himself. Singletary says, he hadn’t considered himself much of an artist, as he didn’t draw and wasn’t trained in traditional Tlingit art styles. In school, though, he leaned into what he was learning about design and sought inspiration from art books. Soon enough, he began to mold his personal style. In the current exhibition, his work with more representational glassworks is evident, as is the influence of music on his art.

Singletary has worked not only to craft the exhibition, but to find the right story to tell. There are several well-known variations of the "Raven and the Box of Daylight" story, each offering new details. Singletary narrowed his work to five versions from four prominent storytellers, including Porter. “The more I dove into aspects of the more descriptive stories, I was able to extrapolate more visceral language that I was able to translate into the glass sculpture,” Singletary says.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/b2/a6/b2a6c8f9-2052-44c4-849c-50c51c82fb87/preston_singletary_071.jpg)

These individual details and events shape his exhibition. On his quest for light, the raven first turns into a speck of dirt, hoping to be scooped up in the drinking ladle of the nobleman’s daughter. However, a telling of the traditional story by Tlingit elder Sophie Smarch offers up a dilemma. In her version of the story, the nobleman and his family have attendants. In addition to cooking food and fetching materials, the attendants are responsible for testing the purity of drinking water with a feather.

As Smarch’s telling goes, the raven quickly gets caught up in the feather, failing to make his way to the nobleman’s daughter. Captivated by this detail, Singletary sculpted a feather with a droplet hanging off the bottom. Inside the droplet is a single dot: raven caught as the attendant foils his first plan.

For Singletary, telling the right story also involved immersing viewers in the exhibition. Building on his passions for music, magic and camera obscura, he wanted his “Raven” exhibition to not just be a collection of glassworks, but an act of storytelling. The raven physically journeys through a sculpted clan house entrance, marking the inside-outside divide within the exhibition.

“As you pass the [raven] transformation area and you walk into the clan house, [the Smithsonian fabricators] built doorways so it did really feel like you were stepping into a house,” says guest curator Miranda Belarde-Lewis, who is enrolled at Zuni Pueblo and is a member of the Takdeintaan Clan of the Tlingit Nation. “It’s just a stunning way to add even more of an immersive quality to being inside of a story.”

One of Belarde-Lewis’ main roles, in addition to helping Singletary sort through variations of the raven story, was working with the dance and visual arts team zoe | juniper to develop a multisensory experience.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/06/63/0663c29a-9f7b-4556-863c-e4fe1277b90e/singletaryravenboxdaylight_41_hr.jpg)

Throughout the exhibition colorful projections guide the raven from the outside to the inside of the clan house and then into the newly bright world. Music and recordings of the Tlingit language create an auditory experience, and other visual elements such as a trail of smoke aid in building the show's immersive experience. “Sometimes you hear a raven cawing, at different points you hear a man speaking in Tlingit, and a woman speaking in Tlingit,” Belarde-Lewis says. “We purposely did not translate them. We wanted folks to just experience the Tlingit language.”

While Singletary says he is proud of how the entire exhibition came together, he is especially pleased with the opportunity to incorporate a unique soundscape and other audio-visual elements. “I [am] a musician trapped in the body of a glass blower,” Singletary says. “[Music] would have been my chosen profession, but it didn’t really pan out for me.” While the artist is perhaps best known for his glassworks, he continues to pursue music through his band Khu.éex’.

Guided by music, glimmering lights and spoken word, the raven, while in the form of a human, eventually achieves his goal of releasing the light. Capturing this, Singletary sculpts everything the raven might have seen in this new world. With projections from zoe | juniper bathing the glassworks in bright light, creatures of the sea, land and air take shape, unveiling a rainbow of different colors and textures. “It showcases Preston’s evolution as an artist,” Belarde-Lewis says. “Throughout, he’s pushing himself… to show his abilities as a glass artist. It’s an incredible display.”

For Singletary, the show “Raven and the Box of Daylight” serves as a “benchmark” in his career, but he hopes it also provides a new awareness to viewers. “Be aware that as contemporary Native American artists, our work was largely excluded from the modern art world for most of history,” Singletary says. “This is a way of bringing an art exhibit to a larger audience so that it can take its rightful place in concert with all of the art that is happening here in D.C. and all of the great things to learn about and see.”

“Preston Singletary: Raven and the Box of Daylight” is on view at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of the American Indian through January 29, 2023.

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

:focal(800x602:801x603)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/8b/c9/8bc98636-82a9-4b08-94c5-b9fdc6142488/untitled-1.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/sarah.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/sarah.png)