What Do One Million Index Cards, Stacked Atop Each Other, Look Like? Artist Tara Donovan Does It Again

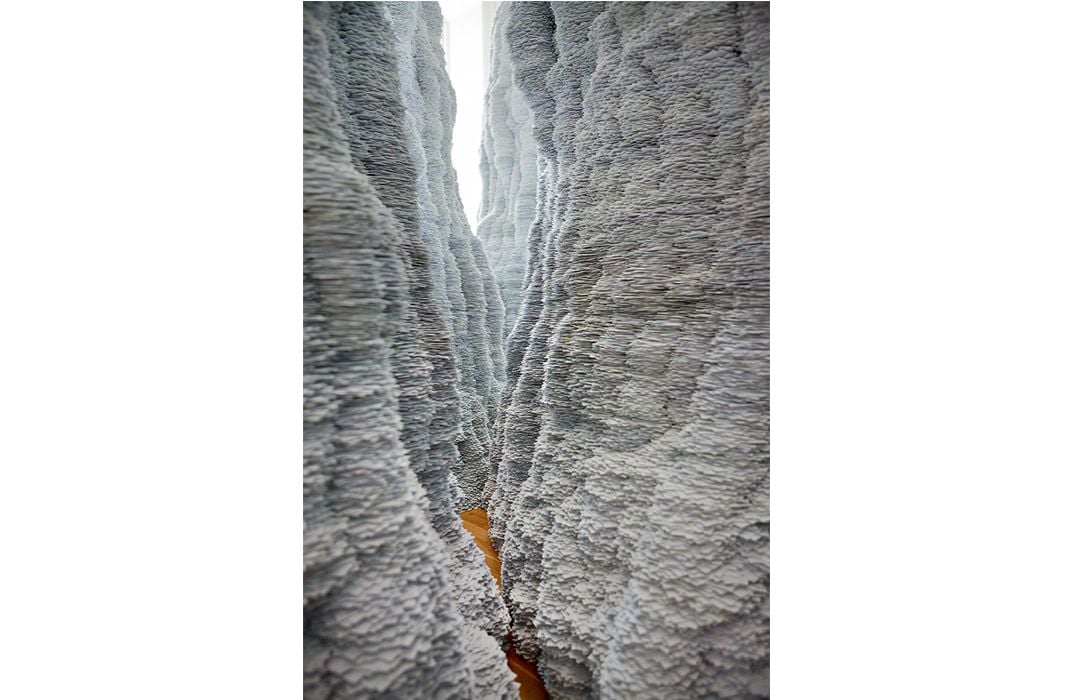

The artist’s looming installation recalls the volcanic fairy chimneys of Turkey’s Cappadocia region

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/c7/38/c7386585-cddc-42f2-905e-ddcf1083ecaa/donovanuntitledweb.jpg)

Sculptor Tara Donovan does not mix metaphors or mediums when practicing her art.

She uses just one type of building block, which in the past has included buttons, plastic cups, or toothpicks, to explore the “effects of accumulating identical objects.” Through various processes that include layering, bundling and piling, Donovan transforms these everyday, mass-produced objects into room-sized sculptures that evoke organic structures and otherworldly geography.

“I am really interested in seeing how individual parts can dissolve into a whole,” she says of her installations that are often expanded and contracted to fit different spaces.

For the "Wonder" exhibition, marking the reopening of the Renwick Gallery of the Smithsonian American Art Museum, Donovan constructed 10 towers by stacking and gluing hundreds of thousands of index cards on top of each other. These towers, which range from 8 to 13 feet tall, form irregular, looming spires reminiscent of the hoodoo rock formations found in Utah’s Bryce Canyon or the volcanic fairy chimneys of Turkey’s Cappadocia region.

Donovan describes her work as “playing with materials in the studio and then being very open to what the materials are doing.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/c7/85/c7857bfc-871c-47f3-a3d4-7d83f693c5db/donovanbyschildhornweb.jpg)

“Training myself to always look for idiosyncrasies has been essential to the development of my practice. I often find myself not even looking at an object, but rather the way it relates to the space around it,” she says.

The Brooklyn-based artist, with her short, black, bobbed hair and oversized Tom Ford glasses, spends hours experimenting with the individual components of her sculptures. Once she’s tackled that, she spends additional time devising a system for assembling the units into an integrated whole.

“I have false starts and total failures on a regular basis. While I have given up on certain items, I usually keep things around because time has a way of allowing fresh approaches to develop,” she says.

Donovan admits that her Long Island City studio is “littered with small samples of materials that hold some sort of potential for me.”

In conversation, the New York native offers the relaxed, efficient banter of an experienced waitress and bartender, which are the jobs that sustained her through art school and the early years of her career. She credits waiting tables with teaching her to multitask, which she believes is “a valuable life skill” that has been quite useful in developing her work.

For the actual production of her sculptures, which involves labor-intensive repetition, Donovan enlists the help of a team of seasoned assistants.

“I have some people who have worked with me for over a decade. Oftentimes, those who have been here longer take on the task of working with newer recruits to adapt their working methods to achieve the results I envision,” she says.

The sculptor demurs when asked if the actual construction of her mammoth pieces can seem tedious. “If I keep my focus on the final outcome, the production of a work can be a kind of meditative journey in its own right,” she explains.

Donovan burst onto the contemporary art scene in 2000 when, as a newly minted masters of fine arts graduate from Virginia Commonwealth University, she was selected for inclusion in the Whitney biennial. This trendsetting show at New York’s Whitney Museum of American Art has long served as a showcase for promising young and lesser-known artists. Donovan’s piece, Ripple, a large floor installation made of small pieces of copper electrical cable arranged in cascading dunes, was widely praised. Despite the acclaim, she did not quit her waitressing job until 2003 when her first solo New York art show solidified her reputation.

Recognition and awards quickly followed. In 2005, Donovan was the inaugural winner of the Calder Foundation Prize, which enabled her to complete a six-month residency at famed American sculptor Alexander Calder’s studio known as the Atelier Calder in Sache, France. While there, she worked with panes of glass that she broke into jagged shards and then assembled into a large piece that evokes geological strata. In 2008, she was awarded a MacArthur fellowship, commonly called a "Genius" grant, which came with $500,000 in “no strings attached” funding to support her work.

“It was an incredible honor. The ‘genius’ moniker is something I will probably never be comfortable with. The funding certainly allowed me to expand my practice in directions that weren’t possible before,” she says.

Donovan set her sights on becoming an artist in high school, when she decided to apply to art schools instead of traditional college. She attended the School of Visual Arts in New York for one year, but then transferred to the Corcoran School of Art + Design in Washington, D.C., from which she graduated in 1991.

“I think you have to commit to defining yourself as an artist early on if you ever hope to become one,” she maintains. The sculptor also admits that she “never really explored any other careers.”

One concept that she is ambivalent about articulating is the notion of “inspiration,” which she feels is often romanticized. “I think it is something you need to work very hard to achieve. It’s not something that just drops out of the sky,” she explains.

She also finds it difficult to pinpoint what draws her to the objects, like index cards, that she uses to construct her work.

“If I had a very specific answer for this, my life would be a lot easier, because I would always know what it is that I am going to do next. A lot of times, its just a matter of taking up a package of this, or a package of this and then messing around with it,” she says.

In planning future work, Donovan says that she does not have a storehouse of items waiting in the wings, but she has been considering the possibility of creating an outdoor public project.

But, before any new sculpture is unveiled, Donovan knows that she must have an answer to the inevitable question that she faces whenever she completes a new installation.

“There is a kind of instinctual ‘Guess how many?’ prompt involved with seeing each project,” she explains. “The quantity is simply a matter of achieving the goal rather than a counting game for me,” she continues.

In this case, the answer is about a million. That’s how many index cards were transformed into 10 spiral towers, which make up one of the installations created by nine leading contemporary artists to celebrate the reopening of the historic art museum.

Tara Donovan is one of nine contemporary artists featured in the exhibition “Wonder,” on view November 13, 2015 through July 10, 2016, at the Renwick Gallery of the Smithsonian American Art Museum in Washington, D.C.

Tara Donovan

Wonder

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Lucy_Harvey_151120_1745_WEB.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Lucy_Harvey_151120_1745_WEB.jpg)