Ask Smithsonian: Are Cats Domesticated?

There is little genetic difference between a tabby and a wild cat, so scientists think the house cat is only domestic when it wants to be

Given the subjective nature of the question, there may never be an answer as to whether dogs or cats make better pets. But in all likelihood, dogs were domesticated long before cats—that is, if cats are actually even domesticated.

Dogs have been by man’s side for tens of thousands of years, and have come to rely heavily on the symbiotic relationship with humans to survive. But cats entered into the human sphere relatively more recently, probably around 5,000 to 10,000 years ago, and can still do well without someone opening a can for them.

Scientists say there is little that separates the average house cat (Felis Catus) from its wild brethren (Felis silvestris). There’s some debate over whether cats fit the definition of domesticated as it is commonly used, says Wes Warren, PhD, associate professor of genetics at The Genome Institute at Washington University in St. Louis.

“We don’t think they are truly domesticated,” says Warren, who prefers to refer to cats as “semi-domesticated.”

In its simplest form, to domesticate an animal means to tame it, through breeding and training, to need and accept the care of humans. Studies have put the dog’s domestication at anywhere from 18,000 to 30,000 years ago, give or take a few thousand years. The crossover to domestication is thought to have occurred when dogs diverged from wolf ancestors and gradually began hanging around humans, who were a ready source of meat scraps.

For cats, conventional wisdom—and compelling evidence—puts domestication at around 4,000 years ago, when cats were depicted cavorting with their Egyptian masters in wall paintings. They were also made into enigmatic statuary, deified, and mummified and buried, leaving a trove of evidence that they had some close association with humans. More recent studies have posited that domestication may have first occurred in Cyprus, some 8,000 to 9,000 years ago.

And late in 2014, a group of Chinese researchers gave what they said was perhaps “the earliest known evidence for mutualistic relationships between people and cats.” They examined the hydrogen and oxygen signatures of the fossils of rodents, humans and cats who lived in a village in China some 5,300 years ago. The scientists found a pattern: all ate grain, with the cats also eating rodents. Archaeological evidence at the site indicated that the grain was stored in ceramic containers, suggesting a threat from rodents. The researchers theorized that because the rodents were a threat, the farmers decided it was good to encourage the cats to hang around. And the cats got access to easy prey and the occasional handout from humans.

Not everyone has bought into that study’s conclusion, but it’s another potential link to how cats were brought into the domestication fold.

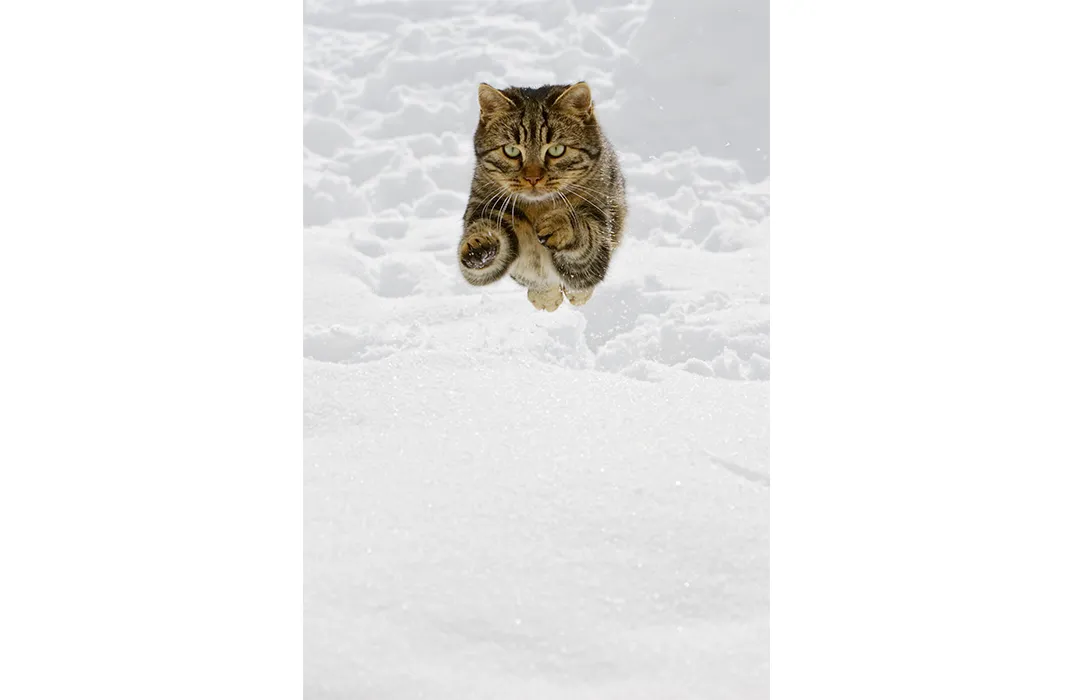

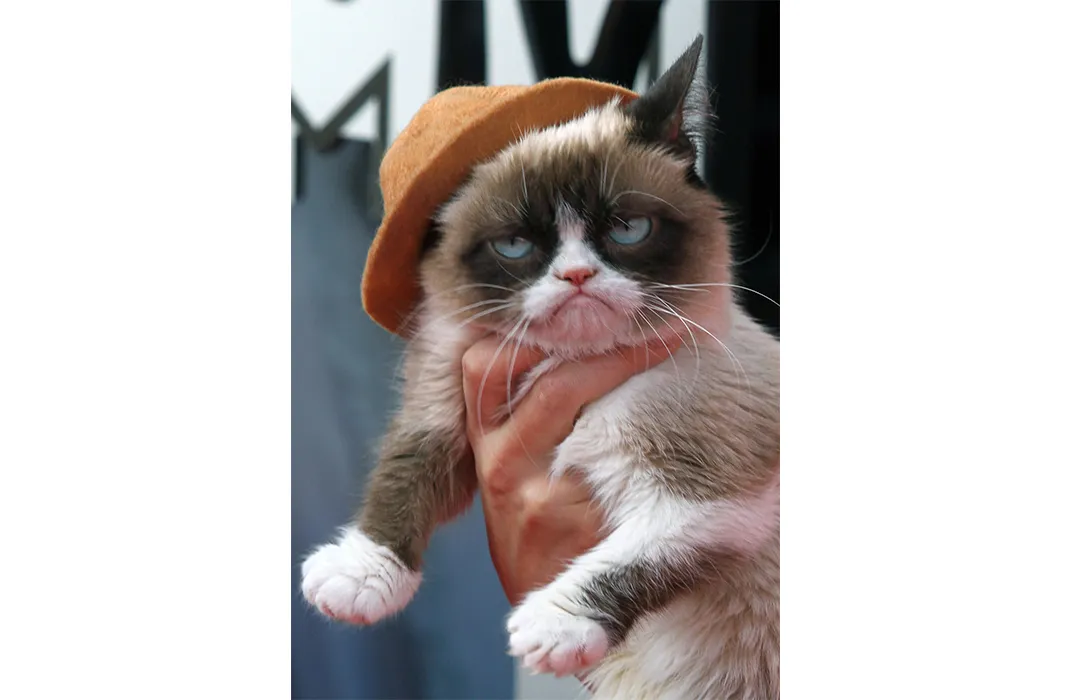

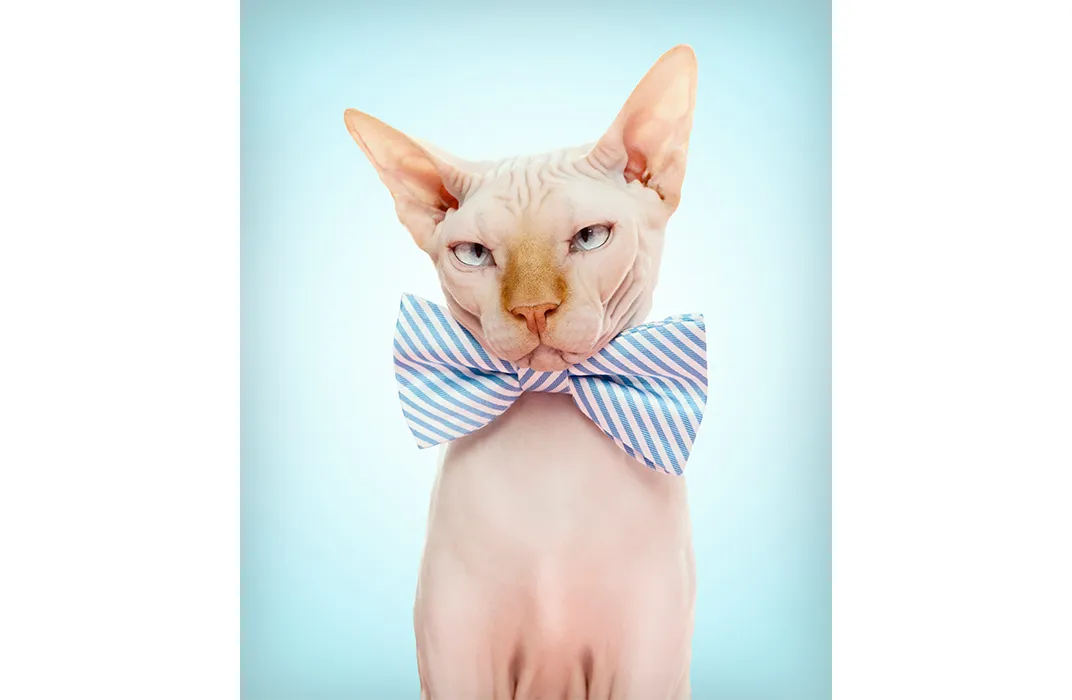

Seven Images To Suggest Cats Merely Tolerate Domesticity

Warren says that he believes that the path to domestication shown by the Chinese study will likely hold up—that there was a commensual relationship between cats and humans, and that humans were attracted to cats as pets. For now, though, he says, it’s hard to know whether the minor taming of the cat has been through human intervention, or if cats have essentially self-domesticated.

House cats and feral cats—those that have become un-tame—continue to breed with wild cats, creating what Warren calls a “churn of admixture.” Cats still retain their hunting skills, and despite having ample supplies of food from humans, will still go out and kill rodents, insects, birds and whatever else they feel like stalking.

The theories of how dogs and cats became domesticated is constantly changing as scientists develop more and better tools, including being able to delve into the genetic evidence.

Warren and researchers from his Genome Institute and from academic centers around the globe recently used genomic studies to take a closer look at how, why, and when cats may have taken a step closer to domesticity. They mapped the genome of Cinnamon, a domestic female Abyssianian cat who was involved in other studies at Washington University, and compared her genetic sequences to that of a tiger, and also to a cow, a dog, and a human.

It was already known that the felix catus genome is not so different from the felis silvestris, but Warren did find some differences from the tiger, especially in areas of behavior. Essentially, they found genes controlling neuronal pathways that would make the domestic cat more willing to approach humans and interact with them—and to seek rewards—says Warren. The same genetic sequences are starting to be found in rabbits, horses and some other domesticated animals, he says.

‘The more we look at this question of tameness or domestication in these different species, we believe we’re going to see more of these genes overlap, or more likely the pathways the genes reside in,” Warren says.

This is not evolution, but the effects of human interventions. Dogs have been much more selectively bred than cats over the years—for specific traits like herding, or security, for instance—and the 400 officially recognized breeds far outnumber the 38 to 45 cat breeds, he adds.

Cats have been bred mostly for fur color or patterns, and yet, a domestic tabby cat’s stripes are no different than a wild cat’s stripes, he said. And, “cats have retained their hunting skills and they’re less dependent on humans for their source of food,” he said, adding that “with most of the modern breeds of dog, if you were to release them into the wild, most would not survive."

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/AliciaAult_1.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/AliciaAult_1.png)