How Thousands of Dead Bugs Become a Mesmerizing Work of Extraordinary Beauty

With much love for the insect world, artist Jennifer Angus crafts an installation made entirely out of beetles, cicadas, katydids and weevils

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/28/c6/28c60946-2a42-4766-aaa9-01314ad9170b/angusinthemidnightgardendetail3web.jpg)

Jennifer Angus’ artwork is startling, especially when it dawns on you that what is on view is not beautifully drawn, patterned wallpaper. Depending on your mindset, it's either a nightmarishly freakish, or beautifully mesmerizing assemblage, of insects.

Beyond the visceral gut reaction, a deeper provocation comes with the ideas behind her work—what is beauty? What does it say about the power of nature, or man’s quest to control nature? What about man’s impact on the planet?

Angus, whose In the Midnight Garden is on display at the Renwick Gallery of the Smithsonian American Art Museum in Washington, D.C., does not shy away from expressing her own thoughts about what might otherwise be taken as an abstraction. She aims to play with perceptions, to challenge hard and fast beliefs about the insect world, and to stir a broader thought process.

Over the last decade or so, she’s specialized in what she calls “a kind of over-the-top grotesque aesthetic,” pinning dead insects to gallery walls in installations that evoke a fussy but dark Victorian sensibility. The show’s curator Nicholas Bell pushed her to go beyond her routine, says Angus. “As I tried to consider it in a more contemporary way, I loosened up a bit,” she adds.

The installation has its orderly parts—neatly arranged patterns of concentric circles, squares and other shapes—all made up of a variety of insects, including thorny sticks (Heteropteryx dilatata), moving leafs (Phyllium giganteum), white-winged cicadas (Ayuthia spectabilis), clear-wing cicadas (Pompoina imperatorial), blue-winged cicadas (Tosena splendida), brown-winged cicadas (Angamiana floridula), katydids (Sanaa intermedia), green stag beetles (Phymateus saxosus) and several varieties of grasshoppers.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/16/f5/16f5f117-41a2-4796-a157-6bc12ecb11ba/angusbycnweb.jpg)

But it’s also animated by swarms of cicadas seemingly ready to fly off the walls. Six oversized skulls—outlined and filled in by hundreds of weevils (Eupholus species)—anchor the installation as a recurring theme at chair-rail level.

A pinkish floor-to-ceiling wash—a dye extract that comes from the cochineal, a scale insect—gives the whole scene a Day of the Dead feel. “The skull is a potent motif,” says Angus. It has become iconic in pop culture, but is also still a signifier of death. Indeed, she’s using them as a reminder to viewers.

“There are at least 5,000 dead things in here,” she says. But she wants that to be a conversation starter, and expects that many people will come in and ask—how many thousand of insects died for this show? It’s a good question, Angus says. “I want people to ask that.”

None of the insects she uses are endangered. There are disappearing species, “but most of them are threatened because of loss of habitat, not over-collection,” she says. Insects—a renewable resource—are at risk because of human incursions, Angus says. But, unlike birds, or bees, or turtles, or whales, or wolves, “insects aren’t so sexy,” she adds. They are important, however, to the ecosystem, pollinating plants that humans and animals need to survive, and decomposing matter.

“We are in a culture where insects are not very highly valued,” agrees Bell. Angus puts them in a setting that forces people to pay attention, he says. At first, they might not realize what they are seeing, but as they get closer, it becomes clearer that they are, indeed, “surrounded by very large dead insects,” says Bell. “That’s an interesting thing to watch.”

The insects in her show are perhaps less threatening than those encountered at home or in the wild, in part because they are dead, but also because she’s imposed some order on them. And, they are colorful and beautiful in their own way. Angus hopes that people “will think about insects differently when they leave,” she says.

In the process of viewing the exhibit, “people have to negotiate their preconceived concepts about what insects are, and I think that’s okay,” says Bell.

Angus has not always been the insect lady. It’s something she came to accidentally.

The Edmonton, Alberta, native’s first love was archaeology, an interest that fizzled out in her first year at the University of British Columbia. She blamed her waning focus on a boring professor and dropped out of school. While working ten days on and five days off on a ferry that ran between Vancouver Island and Vancouver, she began taking art courses—like weaving. She found a new love—patterns.

It gave her a new direction. So she pursued and won a bachelor of fine arts degree from the Nova Scotia College of Art and Design in 1984, and then a master of fine arts from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago in 1991. Ten years later, she joined the University of Wisconsin, Madison, faculty, where she is now a professor of design studies.

That position gives her the luxury to pursue her art. Her initial interest was in textiles, more specifically, the patterns that can be created with cloth and other textiles. She has designed textiles and wallpaper. And she’s studied the interweaving of culture and cloth—that is, what patterns say about the wearer or the society. During forays to Southeast Asia, for instance, Angus learned that textile patterns often signify status or tribal identity, or even that the wearer is pregnant.

On a trip to northern Thailand in the mid 1980s, she saw a woman from the Karen tribe wearing a “singing shawl,” that had fringe decorated with what appeared to be shiny green fake fingernails, but were in fact the hard exterior wings of a type of beetle.

It was a pivotal moment; she’d never thought of insects as beautiful, merely as annoyances. She was “entranced,” she says.

The notion of weaving her two loves—patterns and insects—together began to evolve over subsequent trips to the Southeast Asia in the early 90s. During an art residency in Tokyo in 1995, Angus started creating insect dioramas—complete with kimono-wearing rhino beetles. She was aided by a few schoolboys who were regular visitors to her studio, and like her, shared a fascination for insects. Angus learned that in Japan, it is not uncommon for children to keep insects as pets.

The project sort of reached a natural conclusion—over a period of five years—with, literally a three-ring Bug Circus. In that piece, created in 2000, she posed insects as strongmen lifting weights in one ring, a lion-tamer scenario in another, and two beetles at a water bowl in the third. Angus then began doing fuller installations that incorporated both insects and elaborate patterns. “Pattern can be just a visual stimulus, but it has the potential for so much more, to tell a story,” says Angus.

The stories Angus tells in her pieces are of transformation—from the unknown to the known, from off-putting to enchanting.

Each insect has a story: where it came from, how it was collected, how it ended up in her possession, how she prepared it for exhibit, and how it was chosen to be a part of her art. She has a collection of at least 30,000 insects, ranging in price from 25 cents to $20 apiece, which are re-used from show to show, and put up in storage in plastic bins (with mothballs to ward off insect predators like mites) at her university and home studios, and a one-room schoolhouse she has converted.

She purchases the insects primarily from a dealer in France, who, in turn, sources them mostly from indigenous people in Southeast Asia. If she can get farmed insects, she will use them.

“I get pretty much the same three questions all the time: are the insects real, is this their natural color, and do I collect them all myself,” she says. The insects are definitely real, none have been color enhanced, and she never collects them herself, although she does prepare them when they arrive from the dealer by humidifying them and placing them with stainless steel entomological pins on foam board.

Angus has digitized photos to scale of every insect in her collection, which she uses to design the exhibition, once she knows the floor plan. It has to be tightly designed. “I have to know how many insects to bring,” she says adding, “I can’t go, ‘oh, I wish I brought more cicadas.'”

For the Renwick show, she and two assistants drove the insects from Wisconsin. Once in the gallery, Angus and the assistants began the arduous, multiday process of hammering the pinned specimens into place according to her design plot.

Angus chooses particular species for their wow factor, but also for their durability, and how well they fit into specific patterns. Some insects will never be a part of an Angus exhibition. Cockroaches, for instance. “It’s almost like it’s so obvious that it’s not worth doing,” she says. Nor will she use any butterflies because “everybody knows butterflies are beautiful.”

They provide no chance to educate or stimulate wonder.

And that would basically defeat her mission. “I’m trying to rehabilitate the image of insects,” Angus says. She’s hoping that, “Instead of stomping on them or rolling up the newspaper,” people might consider “gently escorting them out the door instead.”

An Angus show always makes a big impression and they have proven immensely popular.

The artist has exhibited in galleries and small museums in Canada, Australia, England, France, Germany and the U.S.

Being at the Renwick offers the opportunity to perhaps make an even bigger impression, in part because people who can affect environmental policy might see the show. But there’s also the general appeal in a big city. “A lot of people who have never walked into an art museum will come because they want to see the big bugs,” says Angus. She expects it to be one of the highest-attended of all of her shows so far.

But she says she’s not ready to make a life-long career of being the insect lady. “Doing these installations is very physical.” While she thinks she’ll eventually become tired of them, she adds, “obviously, this is a significant investment, so they’re going to be around for awhile.”

Jennifer Angus is one of nine contemporary artists featured in the exhibition “Wonder,” on view November 13, 2015 through July 10, 2016, at the Renwick Gallery of the Smithsonian American Art Museum in Washington, D.C. Angus' installation closes on May 8, 2016.

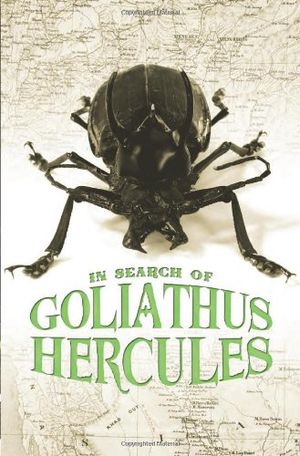

In Search of Goliathus Hercules

Wonder

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/AliciaAult_1.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/AliciaAult_1.png)