At the Sackler, Shadows of History Hidden in Middle Eastern Landscapes

New work from Jananne Al-Ani exposes a complicated history within the Middle Eastern landscape

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/20120824124017Shadow-Sites-Thumbnail.png)

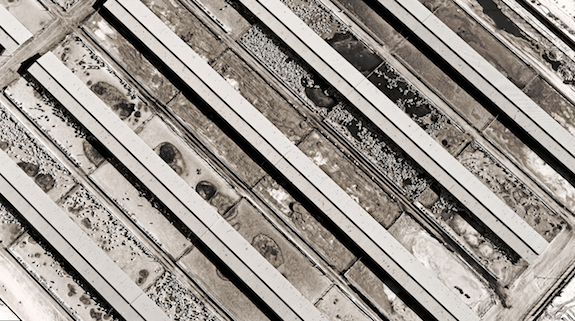

Seen from above, a soft, sepia-toned still of expansive crop circles somewhere in the south of Jordan floats beneath the camera. The image zooms gracefully closer. From such a distance, the landscape is unarmed, decontextualized and calm–like the comforting pan of a Ken Burns documentary. A crescendo of intrusive industrial sounds interrupt the still. The beat of propellers and a blast of static radio transmission erupt over the sequence of aerial images.

This is the dichotomous world of wide-open space and acoustic density that greets the viewer at the Sackler‘s new exhibit opening August 25, “Shadow Sites: Recent Work by Jananne Al-Ani.” The Iraqi-born artist has long been interested in the ways the Middle Eastern landscape has been visually transmitted. From archaeological documents to early military surveillance images, the region has been presented as a blank and ominous background.

Working closely with the Sackler’s collection of negatives and prints from the early 20th-century German archaeologist Ernst Herzfeld, Al-Ani was able to juxtapose her modern footage with historical documents. Split between three galleries, the exhibit begins with Herzfeld’s photographs before moving to Al-Ani’s 2008 piece The Guide and Flock, which features two screens, one with a man walking into the distance along a desert road and a smaller once placed inside the first with a stream of noisy traffic zipping across the frame. The final room includes Al-Ani’s new Shadow Sites installation as well as a small box that allows visitors to peer down on a screen of ants crawling over the desert sand.

“I was very interested in the idea of the disappearance of the body in the landscape through crime, genocide and massacre but also in the idea of the artist trying to remove himself or his presence from the image,” explains Al-Ani, contemplating the persistent desolation that carries into her work as well.

Al-Ani began to consider the enduring legacy of such presentations during the first Gulf War. She cites the work of theorist Paul Virilio and his 1989 text, War and Cinema: The Logistics of Perception, when she describes the dehumanizing effect of a diet of desert imagery that comes out of the Middle East. But it was cultural theorist Jean Baudrillard who applied a visual analysis to both the implementation and presentation of the Gulf War in a series of 1991 essays. Published collectively in 1995 in a book titled, The Gulf War Did Not Take Place, Baudrillard’s writings argue that the new military technologies delivered a hyper-real sense of violence that was at once precise and disembodied. Indeed, the casualties were markedly uneven because of the use of air attacks, supporting Baudrillard’s assertion that the war was in some ways a virtual war. Seen in this context, the calm aerial panorama of a desert landscape takes on a much more sinister quality.

Using research collections from the Air and Space museum on military technology and the Sackler’s collection of Herzfeld’s photographs, Al-Ani was able to highlight the ambiguity of both military surveillance images and archaeological documents. Describing Herzfeld’s records, she says, “I thought his work was very interesting because often he photographed his journey to the site, or the site from such a distance, that you’d almost not be able to see what the subject of the photograph was. They became kind of autonomous landscapes.”

Likewise, her images exist somewhere between the blurred lines of art, documentation and surveillance. And indeed she had to work across multiple agencies, including the Jordanian military to secure permits for filming. After waiting out a rare stretch of rain, Al-Ani was able to take to the sky with a cameraman and pilot to photograph sites, including a sheep farm, crops, ruins and Ottoman military trenches.

Explaining the process and the show’s title, she says, “When you’re up in the air and the sun is just rising or setting in the sky, these very slight undulations that wouldn’t be present on the ground reveal the site as a drawing from above because of the shadows. The ground itself becomes a kind of latent photographic image of a past event embedded in the landscape.”

Al-Ani still hopes to add to the series with similar treatments of landscapes from the United States and Great Britain. Comparing the deserts of Arizona with those of Jordan, her work would connect disparate lands. For now, viewers can survey a visual history of the Middle East right in Washington, D.C.

“Shadow Sites: Recent Work by Jananne Al-Ani” runs August 25 through February 10, 2013. On August 25 at 2 p.m. curator Carol Huh will be joined by artist Jananne Al-Ani to discuss her work.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Leah-Binkovitz-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Leah-Binkovitz-240.jpg)