The scene is hilarious. C-3PO has been cut into pieces at Lando Calrissian’s Cloud City, and R2-D2 has to drag the legless droid back onto Han Solo’s Millennium Falcon.

R2 beeps a comment at 3PO, and the golden droid snaps back: “Of course I’ve looked better!”

This is one of the funnier moments in the much-loved 1980 Academy award-winning film Star Wars: Episode V — The Empire Strikes Back. But for the droids, through all of the Star Wars movies, this has been their vibe—best friends who constantly argue but care deeply about each other.

That’s why they are among the biggest draws at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History in the recently opened exhibition “Entertainment Nation / Nación del Espectáculo.” The show is a long-term, fully bilingual 7,200-square-foot exposition devoted to music, television, sports and, of course, film. The droids C-3PO and R2-D2 take center stage, bringing grins and exclamations from visitors taking in everything from Prince’s guitar to the signpost from the television series “M*A*S*H” to a robe that Muhammad Ali wore while he was training for his championship 1974 bout with George Foreman.

“I think that when visitors see these droids on display,” says the museum’s objects conservator Dawn Wallace, “they’re going to hear their voices. I think they’re going to be able to put themselves in the galaxy these droids lived in.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/7a/e5/7ae5f5f5-0b25-4139-89bf-2382381c9725/gettyimages-607402396-1.jpg)

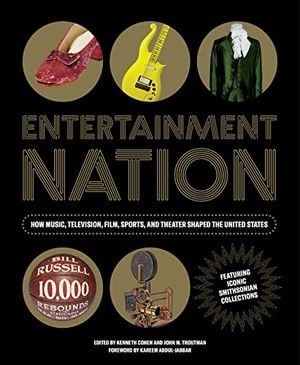

Entertainment Nation: How Music, Television, Film, Sports, and Theater Shaped the United States

U.S. history gets the star treatment with this essential guide to the Smithsonian's first permanent exhibition on pop culture, featuring hundreds of objects like Muhammad Ali’s training robe, and Leonard Nimoy’s Spock ears and Dorothy’s ruby slippers.

Actor Kenny Baker actually sat in the R2-D2 droid on display, and Anthony Daniels really wore the C-3PO costume in the movies, explains museum curator Carlene Stephens. Also, the droids were reused, so she says there’s really no way to tell if they appeared in just one of the first three Star Wars movies or in all of them. But they were certainly in Star Wars: Episode VI — Return of the Jedi. It was after that film that the Smithsonian sought out the costumes for its collections.

“We acquired them about 1983. But it is one of those situations where new research uncovered some additional information. We had a conversation recently with two curators at the Lucasfilm and Disney archives for the ‘Star Wars’ collections,” Stephens explains, “and they told us it’s really hard to tell if [they] were only used in the Return of the Jedi film or if they might have been used in other films before.”

The “Star Wars” universe began in 1977, with what is now known as Star Wars: Episode IV — A New Hope, followed in 1980 by The Empire Strikes Back and in 1983 by Return of the Jedi.

The first of the trilogy burst upon the pop culture scene like fireworks—a rollicking space opera cowboy film with an epic battle between good and evil. There was the heavy-breathing Darth Vader, voiced by James Earl Jones, battling for the fearsome Galactic Empire, and there was Carrie Fisher as Princess Leia, Mark Hamill as Luke Skywalker and Harrison Ford as Han Solo—the young heroes destined to bring victory to the Rebel Alliance trying to restore freedom and justice to the universe.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/01/ce/01ceeb63-5366-4275-9847-f63c511097e3/gettyimages-890989694.jpg)

The first film alone won a slew of awards, including an Oscar for Best Original Score for composer John Williams, and six other Academy Awards, including Best Visual Effects and Best Costume Design. Star Wars changed the way people thought about the movies—with its epic vistas on various planets, a plethora of species and majestically shot space battles that thrilled viewers.

Later, in a prequel series ending with Star Wars: Episode III — Revenge of the Sith, fans watched the descent of Anakin Skywalker into evil as he becomes Darth Vader. Then came the most recent films, a sequel trilogy ending with 2019’s Star Wars: Episode IX — The Rise of Skywalker, not to mention many television animated and live-action spinoffs such as “The Mandalorian” and “Obi-Wan Kenobi.” Throughout the films, fans continued their love affair with droids—including R2-D2 and C-3PO, who had as much personality as their human co-stars.

Actor and puppeteer Jimmy Vee, who played R2-D2 in Star Wars: Episode VIII — The Last Jedi, sees that joy from fans all of time. He says getting the role made him happy as well.

“It really was fun,” Vee says. People follow him around the supermarket and sometimes take 20 minutes to get up the nerve to come and ask him for a picture. For some, Vee explains, it is like solving a mystery.

“They’ll come up and say, ‘We never knew you were inside there, or [that] someone was inside of C-3PO, because it just looked like droids—you know, characters,’” Vee says. “I think that’s what intrigues people is to find out there was actually someone inside them, and then bringing it to life. I think that’s the fascination about us.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/42/68/4268efe5-ed20-4f1b-8684-4c6882541221/smstar-wars-droids-spotlight-jn2022-01023.jpg)

Vee, who stands around 3 feet 8 inches tall, says being inside R2-D2 was quite something. “The only way I can explain it, if you’re in a wheely bin, and closed the lid and sat there for half an hour or 40 minutes, you’re in your own world. You can’t see anything, you don’t hear very much,” Vee explains, adding that he got directions via an earpiece from the director. “And if he says I need a bow, I lean forward. If it’s a shake for excitement, you just get hold of it from inside and give it a good shake. It makes it dance!”

In 2015, Vee took over the role from Kenny Baker, the original R2, who died in August 2016. Vee had worked with Baker on films and other projects, and he says Baker was pleased that Vee got the job.

“Kenny never, ever wanted [R2] to just be a toy. He always believed that if it had someone inside that’s soul, and it brought more fun,” Vee says.

Museum entertainment curator Ryan Lintelman throws fun right in the face of visitors the moment they walk into the exhibition. “On your left, you’ll see the droids, on your right you’ll see the ruby slippers [worn by Judy Garland as Dorothy in the 1939 film The Wizard of Oz], because we want to give the people what they want. They’ll be able to come and see them right away,” Lintelman says.

“Then every three minutes the whole gallery is taken over with this immersive media experience. One of the things that happens is you’ll see tiny fighters flying overhead, and the Death Star exploding right next to them. So it’s going to be pretty cool for fans.”

Stephens recalls how getting what she affectionately calls “these very delicate, plastic things” to the Smithsonian was quite an undertaking. The costumes had to be packed for transport, and then they had to acclimate because they traveled across the country from dry California to the very humid, “practically underwater” city of Washington, D.C. The artifacts sat in a processing facility for a few days and then almost immediately went on exhibition.

“I do remember putting them on display temporarily right inside the front door of the building. It was just in those moments where people saw what was going on and went, ‘Oh my gosh, that’s R2-D2,’” Stephens recalls.

Then, R2-D2 and C-3PO were part of a massive exhibition in the 1990s called “Information Age,” where they were displayed with the intention of juxtaposing them with actual robots. The beloved droids were then off display for quite some time, before undergoing conservation for the current exhibition. Again, it was a journey.

Conservator Wallace says that, for one thing, the team wanted to make the costumes stable and clean them up as well as possible, even though they were made to look as if they were dirty. Plus—there was sand still left inside R2-D2 from one of the scenes. But, she says, the fact that Daniels wore the C-3PO garment and Baker sat in R2-D2 makes them infinitely more special than a standalone object.

“You can see that these androids, their costumes were for filming. They are used. They are banged up,” Wallace says, adding that there is evidence of deterioration, and some of the materials have issues. “There is duct tape holding some parts together, and you can see where they are. They had to change some things on the costumes to make it work for a scene or for filming—little modifications and tweaks. I think it is great. That’s the good part.”

It is clear that Daniels had to deal with a lot performing as C-3PO—wearing a costume made of several kinds of plastic, including polyurethane and polycarbonate, plus some metal components. Wallace says he had to wear a black bodysuit under the outer suit and needed help to get the costume on.

“The legs are all one piece, and you would have to slip on each leg. And then, I don’t know the exact steps, but the rubber center that would have had to go around his torso is the more problematic part, because when he was wearing it, it would have been very flexible so that he could move and bend and twist,” Wallace says.

By now, that part of the costume has stiffened up.

“He would then have this chest piece put over the front and back, and all of these were held together with hex bolts and screws and mechanical fasteners,” explains Wallace, of the costumes that are now both staged and adorning custom-designed mannequins.

“C-3PO is a costume, but he’s a robot and he’s hard. You can’t manipulate any of his parts. You can bend it at the elbow, but you can’t work with it anywhere else. So, finding a way to put this on a mannequin form, I think, was the hardest part, because he is more stable on the mannequin than off. Whenever he is in storage he’s not in different parts. He is always on the mannequin form as his form of preservation.”

Baker had a different road to hoe when he portrayed R2-D2.

“He would sit inside, and they would have a lever so that he could rotate the head and buttons for different lights that he could do. Also, for R2-D2, when he goes in, he has the little arms that would come out. There’s actually on the costume two small, skinny doors that he would have just protruded a tool through to act like those arms,” says Wallace.

During the conservation process, Wallace says the R2-D2 costume was just as sassy to work with as the little droid was in the films.

“Like I said, these were props made for a movie, and they would be altered on set, they would be tweaked. Things were held together with duct tape. So, there would be times when the glue they used 40 years ago was no longer working today, and maybe this one panel would need to be set down again. And as you’re working on it, something else would come loose,” Wallace says with amusement, adding that at times as she worked on the artifact, she imagined she could “hear him laughing.”

The two costumes are on display in an environmentally controlled case. Wallace says because plastic is involved, the droids will degrade over time, and that can be harmful to the artifacts themselves and to other materials nearby. She says the case helps to preserve longevity.

Entertainment curator Lintelman says the droids won’t be talking or beeping, as the museum will leave the animating of the costumes to Lucasfilm. He says for the Smithsonian, it’s about displaying the objects, talking about their historical significance and showing them as the treasures they are. He thinks they illustrate something about the Star Wars film series that was prophetic.

“The thing that set it apart was having this world of the future that was also kind of lived-in and grimy in different ways, too, and I think we see much more of Star Wars in our daily life now than we think we might have when the films first came out,” Lintelman says.

Wallace thinks the costumes speak to visitors of all generations.

“R2-D2 and C-3P0 haven’t changed in all of the films in the whole Star Wars saga, and I think that makes them a permanent fixture,” she says. “I think when visitors see them, they’re going to instantly connect with these droids from the films and from this galaxy that we’ve all envisioned being a part of.”

"Entertainment Nation / Nación del Espectáculo" is on view on the third floor west at the Smithsonian's National Museum of American History.

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

:focal(800x602:801x603)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/a0/59/a0596bee-028c-48a3-9975-60a808b2d7b4/embargoed-star-wars-droids-costumes-jn2022-000011200.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/allison.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/allison.png)