Beyond the Korean Taco: When Asian and Latino American Cultures Collide

Smithsonian Asian-Latino Festival debuts a pop-up art show on Aug. 6-7 in Silver Spring

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/tecate_cr.jpg)

In today’s food truck-obsessed age, Korean tacos have come to symbolize Asian and Latino American cultural exchange. Since July, the Smithsonian Asian-Latino Festival has built off of that flavorful groundwork to examine the interaction of these communities through three lenses: Food, Art and Thought. This innovative collaboration between the Smithsonian Asian Pacific American Center (APAC) and the Smithsonian Latino Center recently concluded its “Gourmet Intersections” program and, this week, takes its show on the road for “Art Intersections,” a public art show popping up in Silver Spring, Maryland, on August 6 and 7. Works by Asian and Latino American artists will be projected onto Veterans Plaza, along with a soundscape of Asian-Latino fusion music. Both programs will feature different artworks: August 6 will explore the theme of migration, while August 7 will have a West Coast focus.

To learn more about the program and its origins, we spoke with three of the festival’s APAC-based organizers: Konrad Ng, director of APAC; Adriel Luis, curator of digital and emerging media; and Lawrence-Minh Bùi Davis, APAC initiative coordinator.

How did the Asian-Latino project come about?

Konrad Ng: This was the outcome of a conversation between the director of the Smithsonian Latino Center, Eduardo Díaz, and myself. We share the same hallway and the same space, and we feel that we share the same mission, just working with different communities. But through the course of just living and working together, we realized that we shared a lot more than just the mission. When you try to understand the American experience and the American story, you have to understand how different communities interact and form the cultural fabric, the cultural history and art of this nation. There is a great deal of intersection—and collision—between Asian Americans and Latino communities in the U.S. We have done a few public programs over the last few years, just to feel that out. . . .

That all came down to the Asian-Latino Festival, and we picked different ways to try to breathe life into this intersection. One is through food, which is a wonderful vehicle for understanding home and identity. It’s a point of contact for lots of people where it immediately brings out a reaction, some emotional reaction that is usually founded in memory. Art. . . captures kinds of expressions that we felt our communities were using. . . . And we also wanted an element of scholarship because this is a project that we want to bring to scale. We want to increase it. We feel that what we’re doing is important. It to the civic culture of the United States by allowing us to understand ourselves in a deeper and more complete way. So we’ve invited scholars and artists from across the country, and also curators and researchers at the Smithsonian, to think about what this so-called field means. What could it look like? How could we create something here at the Smithsonian that would position the Smithsonian at the center of this conversation, of having these incredibly diverse, dynamic communities who have been part of the United States for generations? How can we bring them into the national fold at the world’s largest museum and research center?

What do Asian Americans and Latinos have in common at this particular moment?

Ng: Right now I think the United States recognizes there’s a demographic shift in terms of what our population will look like over the next 50 years. Asian Americans and Latino communities find that they will become in many ways part of the majority in places across the country. Certainly, in smaller communities, Latinos and Asian Americans are close to the majority. So I think that idea that there will be a greater contribution or recognition of us being around, but also knowing that our histories aren’t represented as we feel we’ve lived them. That’s where we find that the United States is us and always has been us. . . . This project is meant to celebrate and show that, and be a point of departure for conversations and ways to envision America, as it’s lived by people across the country.

Lawrence-Minh Bùi Davis: We come back to this idea of siloed thinking. Culture, cuisine, is impossible to understand in a single silo; they’re always intersectional. Pati Jinich was speaking about the Chinese influence in Mexico and how you can’t think about what Mexican cuisine means without thinking about the early Manila galleon trade and Chinese immigration to Mexico and how that influences what kind of ingredients and cooking techniques are used. There’s not this pure, distinct culture that’s separate; they’re always woven together and always changing over time.

Adriel Luis: With the Asian-Latino project, a lot of times the questions that people ask us are along the lines of “What do Latino and Asian American cultures have in common?” Through the process of developing this project, I think the question that has really come to surface has been more along the lines of “What do we not have in common?” I think in the beginning I was very tempted to answer, well, in L.A. there’s Korean tacos, and in Mexico City there’s a Chinatown, and things that were built with an intention of being a hybrid between Asian American and Latino culture. But we’re finding that a lot of the crossings between Asians and Latinos are not necessarily things that were intentionally mounted as a means of camaraderie. More so they are things that exist by circumstance, some of which date back to where we come from.

When we talk about common herbs and ingredients—chili peppers, adobo sauces, things like that—that’s something that through trade became so deeply embedded in our history that we don’t really think of that as an intersection, because it just happened so long ago that now it’s become a staple to our own individual cultures. And then there are things that I think are common to our communities that happened by circumstance of being in America. For example, Asian Americans and Latino Americans both have the experience of sitting in race conversations that kind of stick within the black and white binary, and not knowing where to belong in that conversation. Or immigration issues and having the fingers pointed at us as a people and as a community. The idea of family existing beyond just your town borders or your state borders or your country borders. And then, when we talk about technology, how have those dynamics, such as having family in other countries, shaped the ways that we use the telephone, the ways that we use Skype and the internet and things like that?

It has been as much exploring history as it has been tickling out the things that have been developed more recent, but that haven’t really been capsuled by any institution or organization. What stories are being told right now that haven’t really been wrapped up and packaged? We’re trying to find those and place them in these conversations about food and art and scholarship.

What are the “collisions” between these two cultures—points of conflict or points of contact?

Ng: All of it. I think that what Eduardo and myself wanted to avoid was arriving at a narrative which was entirely smooth. I think that what’s interesting is textures and ambiguity—and tension. And I think that doesn’t necessarily have to mean it’s all negative. So the use of “collision” is to see things that might become “mashed” or “mashable”—communities colliding, then something emerging from that—but also tensions, whether that’s between communities or even within communities. Trying to see what you felt was your community through the perspective of another always opens up space to rethink who you are, and I think that’s a good thing.

Adriel, what was your role in Art Intersections?

Adriel Luis: My approach with Art Intersections is demonstrating that not everything has to be cut and dry, where either this piece of art is just Asian-American or it’s an Asian-American creating something for an Asian-Latino exhibition. Sometimes things just exist based on the circumstances and the environments in which they’re sprouted.

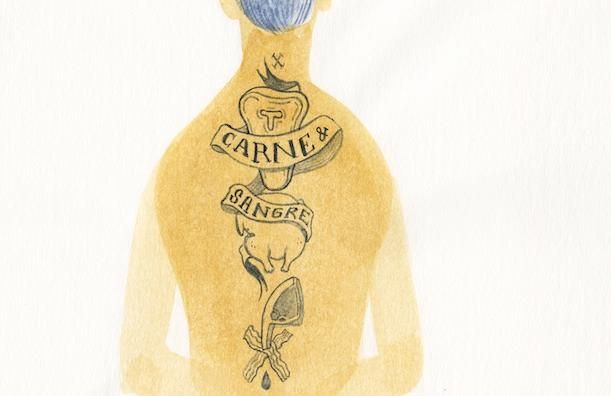

For example, one of the artists, Monica Ramos, is from Manila, went to Parsons and now lives in Brooklyn. set is called “Fat Tats”—it’s different food items tattooed. Some of the pieces use terminology from Filipino cuisine, but the same terminology is also used in Mexican cuisine. As a Filipino, you might look at that work and interpret something, and then as a Latino American, you might look at that work and interpret something similar, but still a bit more nuanced because of where that perspective is coming from.

Some of the work is a hybrid of Asian-Latino stuff. For example, one of the pieces is a rickshaw converted into a low rider. But I think the more interesting aspects of presenting this type of artwork has been stuff that was developed years ago but not in the frame of being an Asian-Latino hybrid. For example, the other curators are from L.A. and a lot of their work is from L.A. artists. So you have Los Angeles, which is influenced heavily by immigrant communities. You have street art that was sprouted in Latino neighborhoods. You have Mexican American artists who are influenced by anime. And you have conversations that are not necessarily in that vacuum. So even as an Asian American, this L.A.-based artist may not necessarily think about these pieces speaking directly just to that community. But if, for example, it is speaking to the L.A. community, then that encompasses so much of what we’re talking about here.

Again, the focus of this project—and I would even say of this festival—is. . . definitely not trying to contrive any types of connections, but demonstrating that more than what we assume exists as a connection is actually out there. And more than anything, the things that we typically tie to one culture and another actually don’t exist in these separate vacuums.

Why Silver Spring?

Davis: We thought, let’s go into Silver Spring as opposed to something in the Smithsonian. Let’s go out into a community, particularly a community that is so rich in cultural diversity and cultural landscape is fundamentally shaped by waves of immigration over the last 50 years. This is a street art and urban culture program, so we want to do something that engages that idea and is literally on top of the street.

Luis: In general, when you ask what the Smithsonian is, a lot of times they’ll say a museum. When I walk around the mall, people ask, “Where’s the Smithsonian?” So to go from that to a pair of units, Latino Center and Asian Pacific American Center, which exist within the Smithsonian but we don’t have a building—we’re a long way away from the person who thinks that Smithsonian is one museum. Part of us having this exhibition and calling it an exhibition in Silver Spring is not just to reach out to immigrant communities there but also to start expanding the idea of where the Smithsonian can exist and where it can pop up. If we just remain in the Mall, then a very small amount of outreach that we can do as a non-physical center. But on the other end of the spectrum, if we can train the community to look at the Smithsonian as something that can exist on their campus or in Hawaii or in Washington state—or something that you can even download and pop up yourself—then for a space like APAC, that gives us a nimbleness that allows us to move much faster than some of the other brick-and-mortar institutions. I think because we are awhile away from having a building and also because museums in general are moving towards digital, we’re also, by just moving a few train stops away, our first step towards creating a national and global presence.