Bill Traylor Depicted His Brutal Lifetime With Vibrant Art

A new Smithsonian show, seven years in the making, takes a deep dive into the life of a self-taught artist and former slave

:focal(1464x1054:1465x1055)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/31/65/31651a3d-5cb5-4b19-bd0b-386183bd6b42/man_with_yoke.jpg)

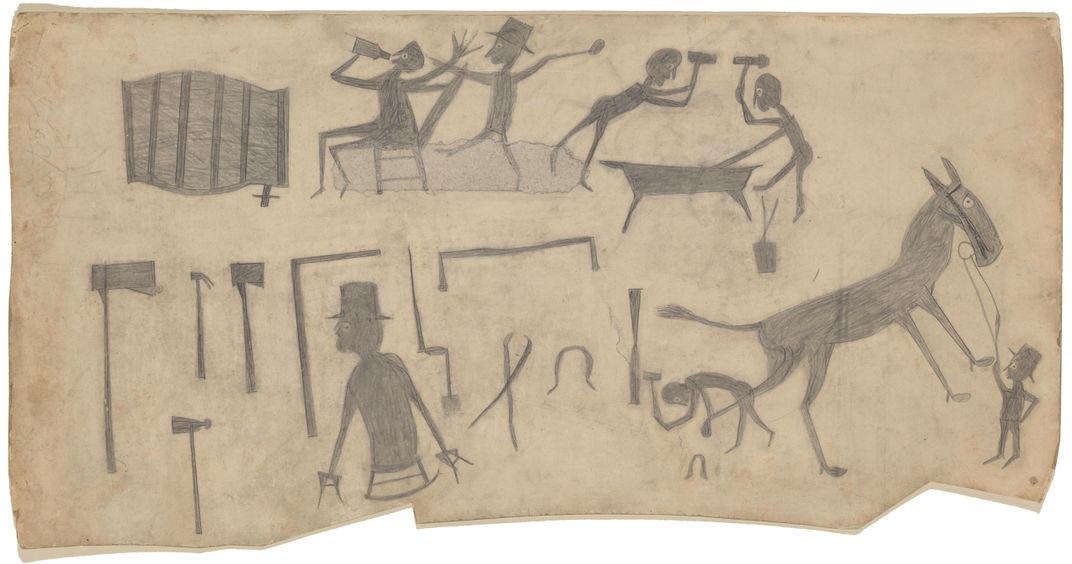

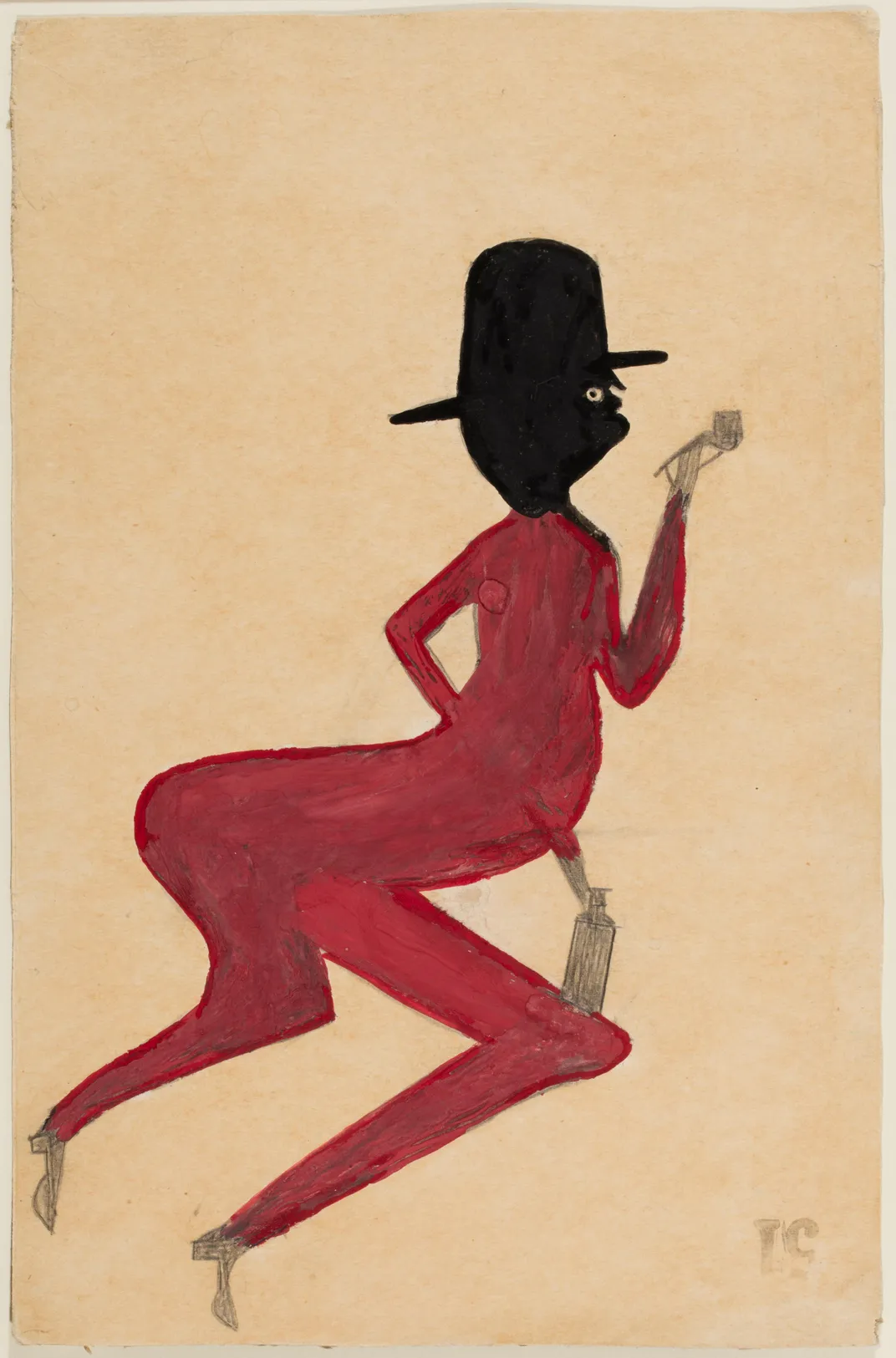

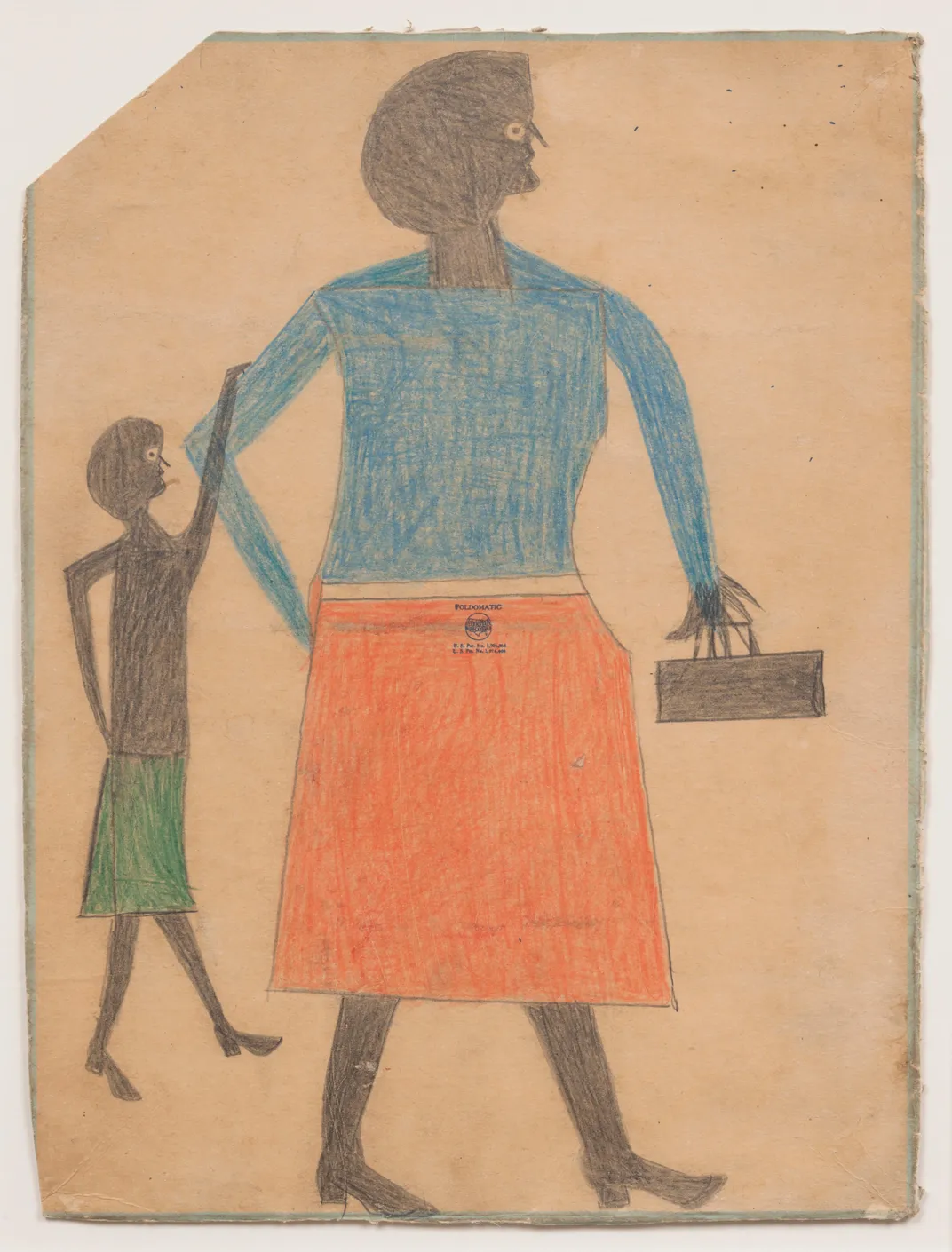

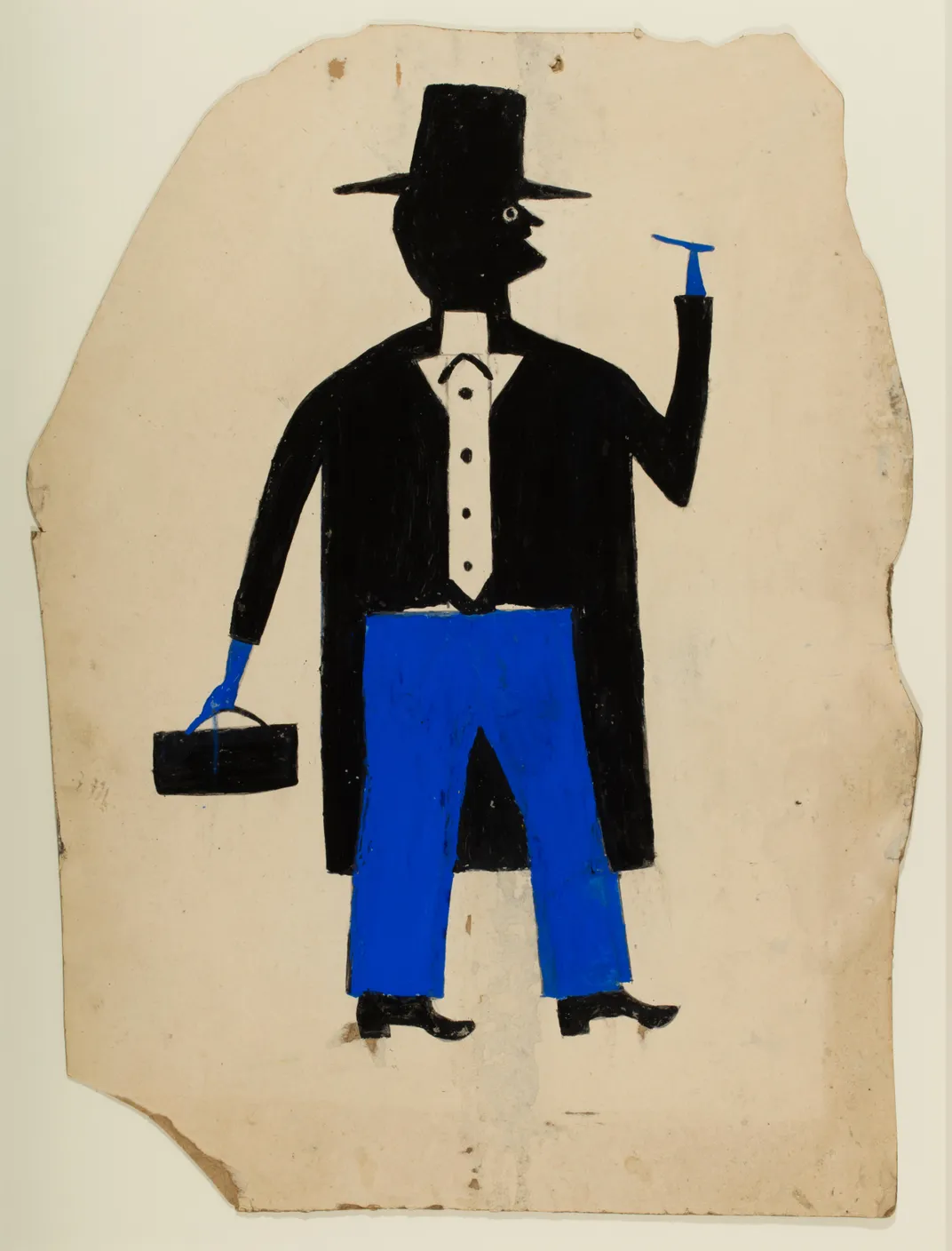

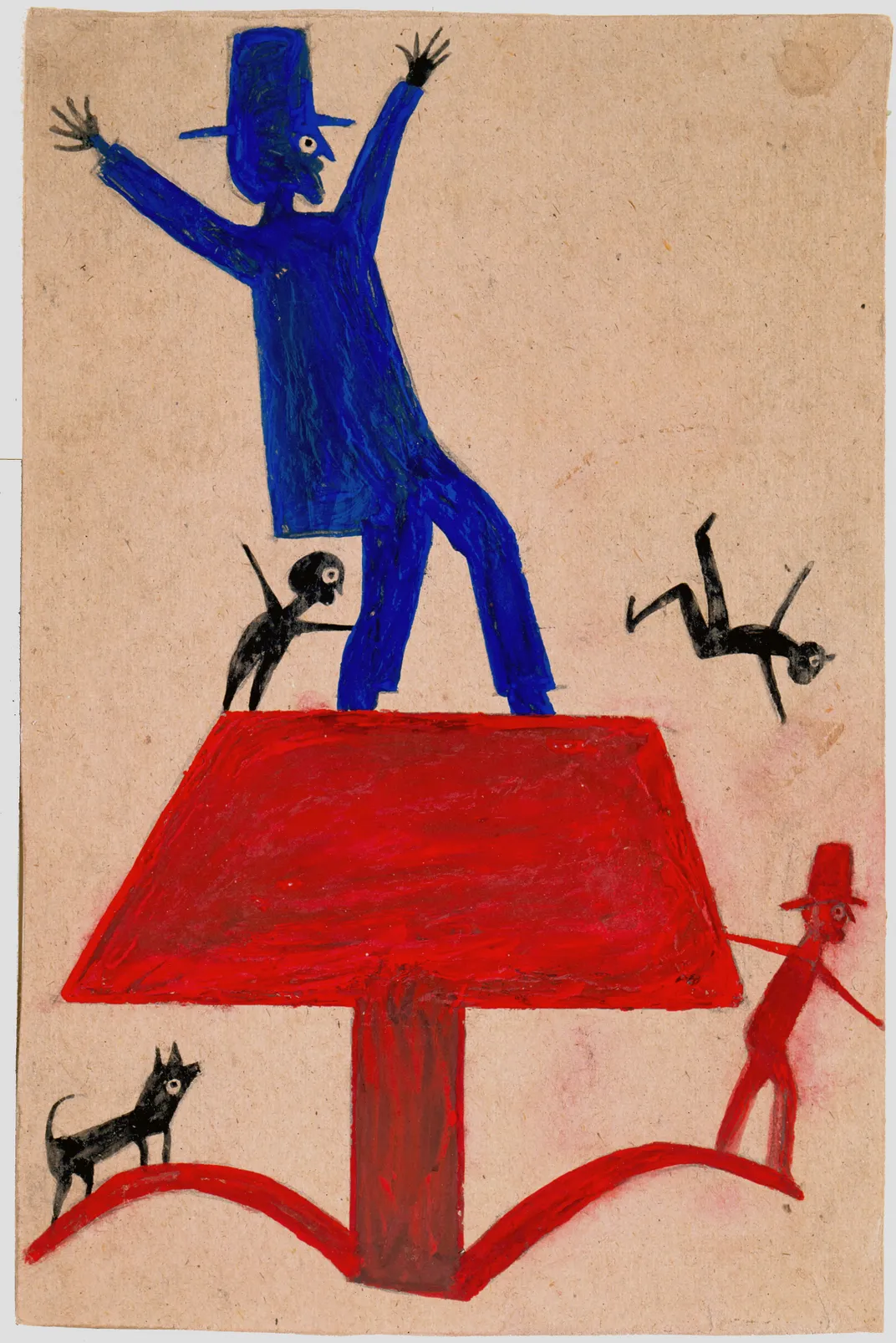

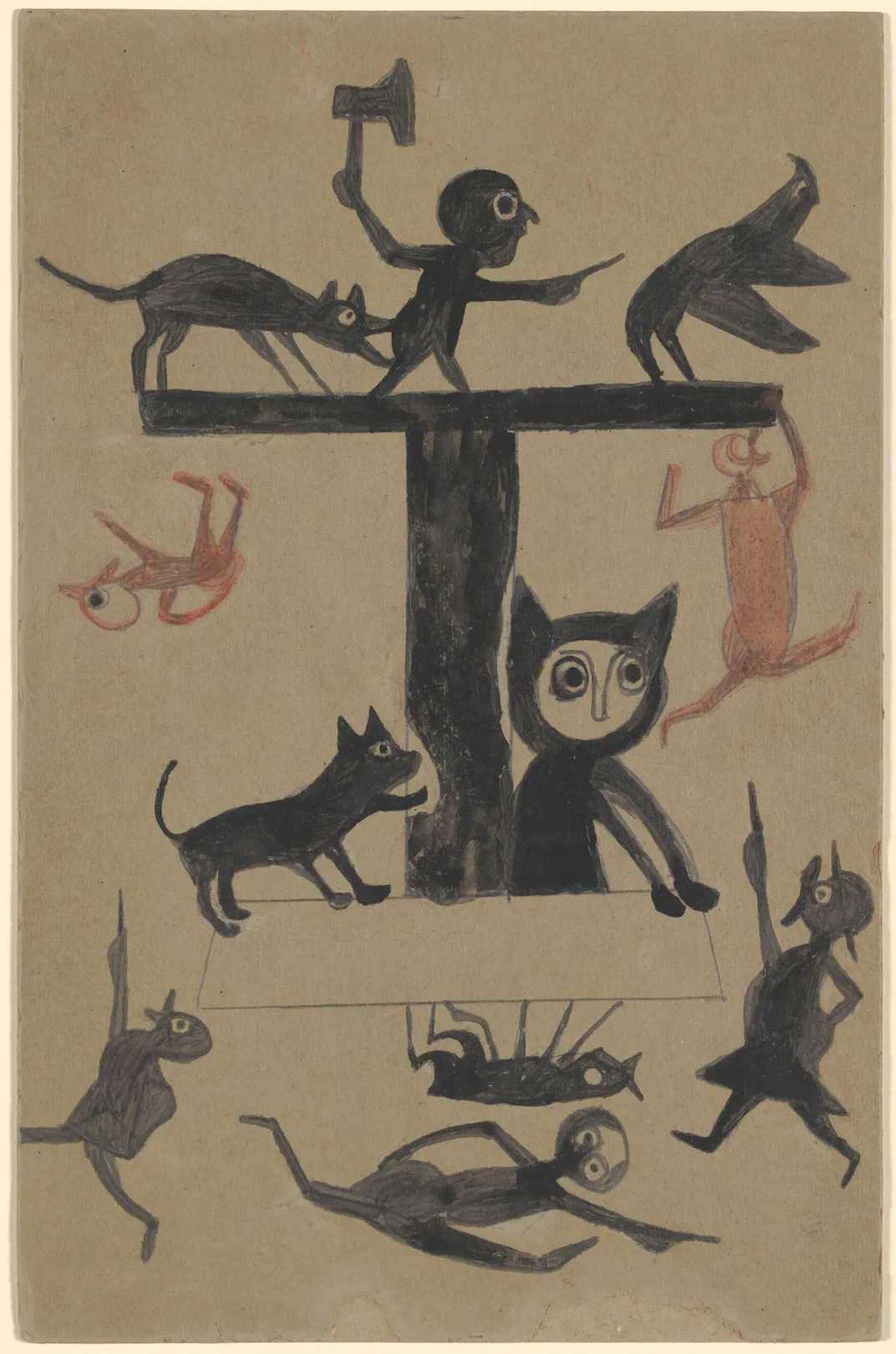

Born into slavery circa 1853, Bill Traylor was witness to the Civil War and Emancipation, lived through Reconstruction, the Jim Crow segregation and the Great Migration. After seven decades of toil, too old and infirm to work any longer, he decided to pick up a pencil and paintbrush. He was thought to be 86 at the time.

Sitting at a small desk on a busy street in Montgomery, Alabama, he turned out more than a thousand images in the next four years. The striking works on discarded cardboard also had a visual immediacy and enough flair to attract the eye of professional artists in town who encouraged and collected the work.

The widest exposure to his work came decades after his death, in the 1982 exhibition “Black Folk Art in America” at the Corcoran Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C. His work began appearing in major museums.

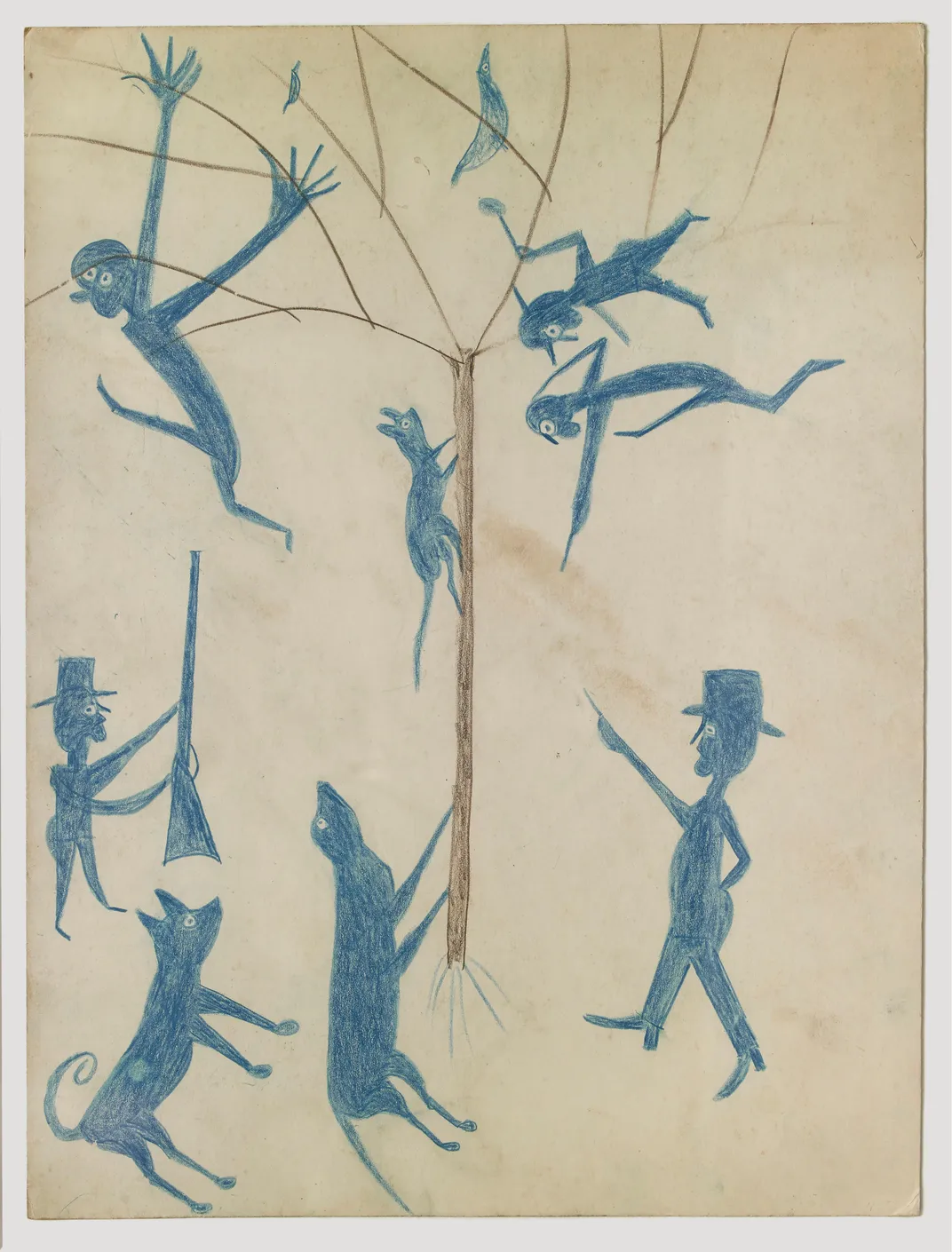

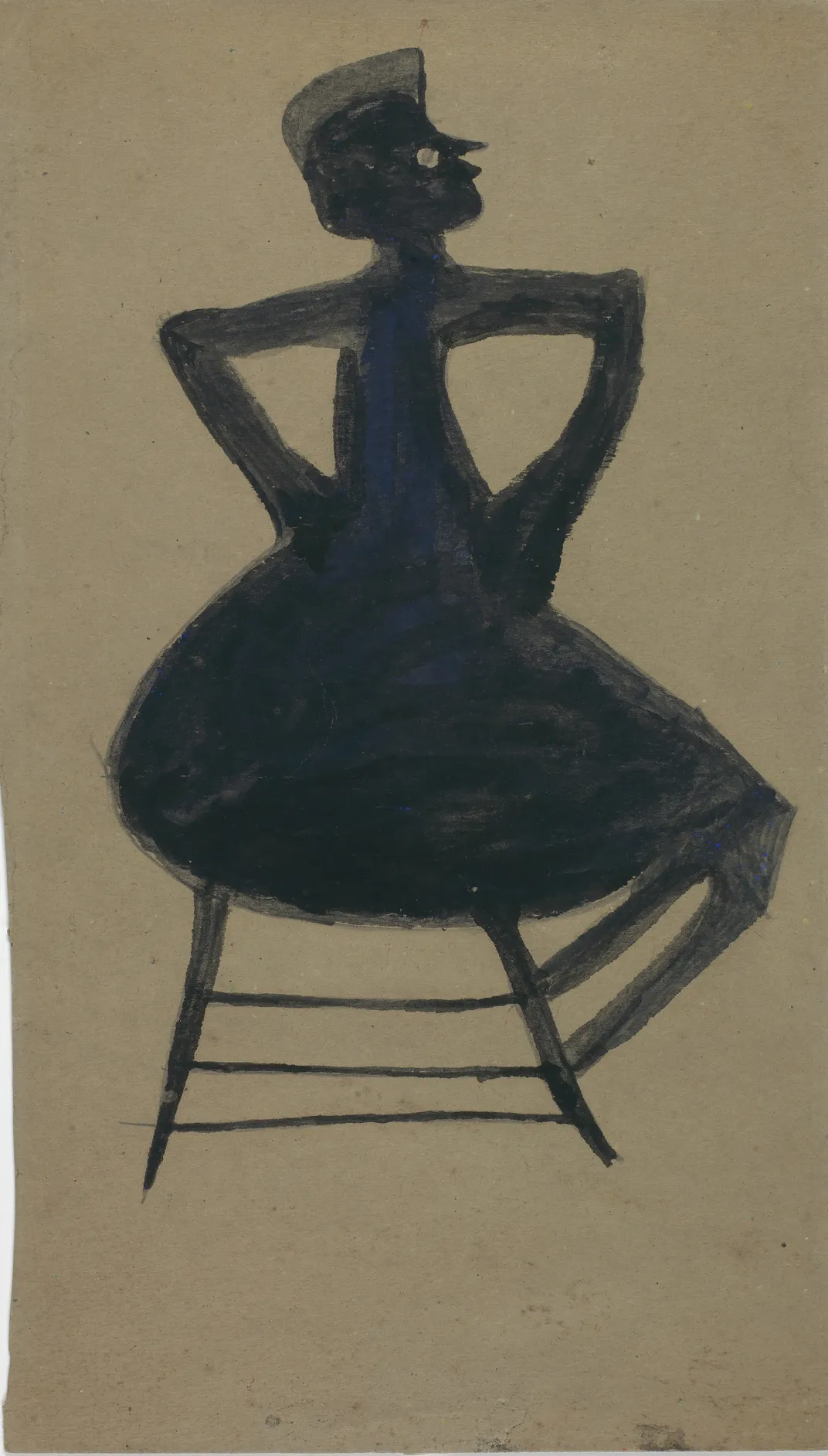

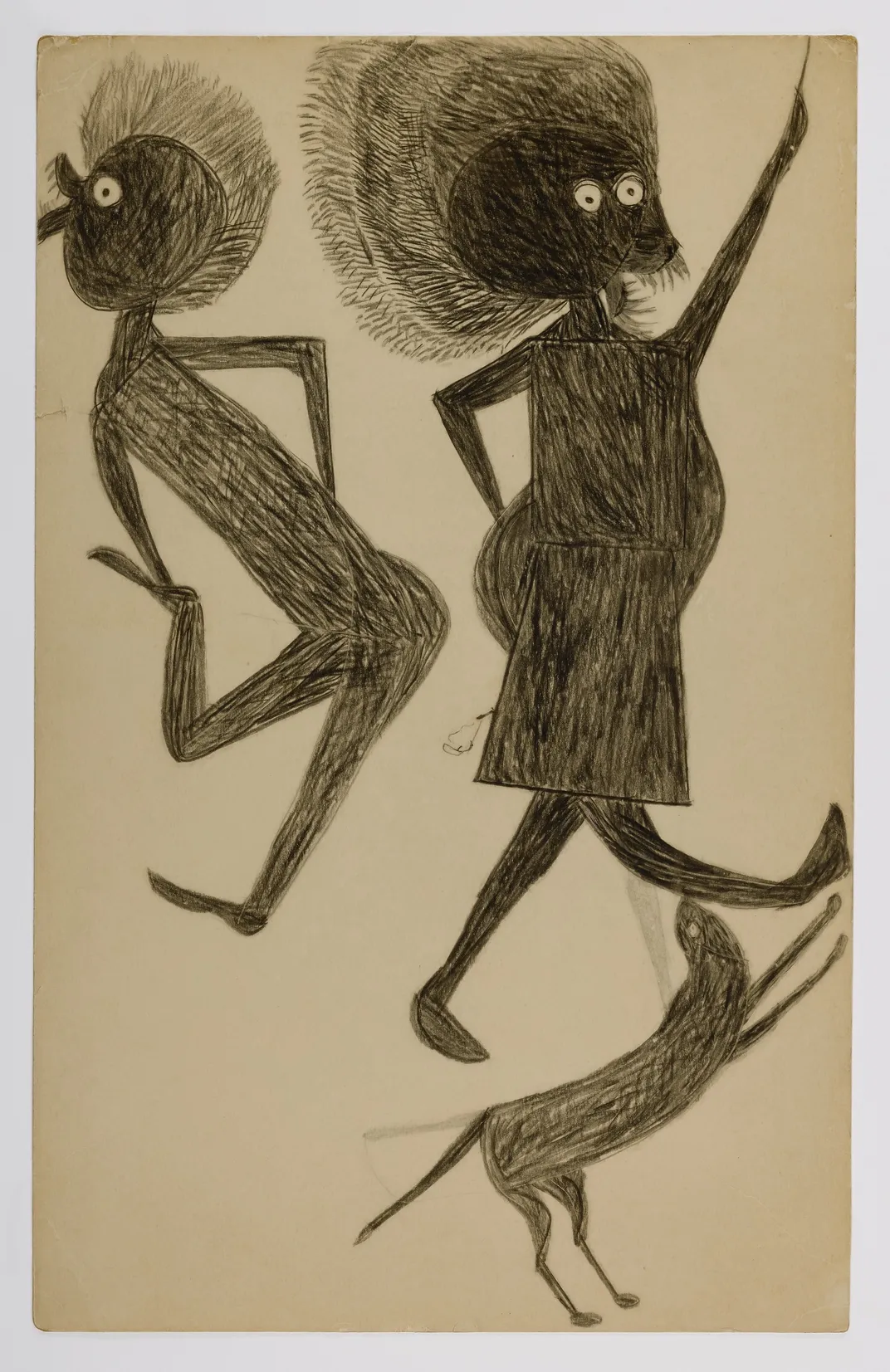

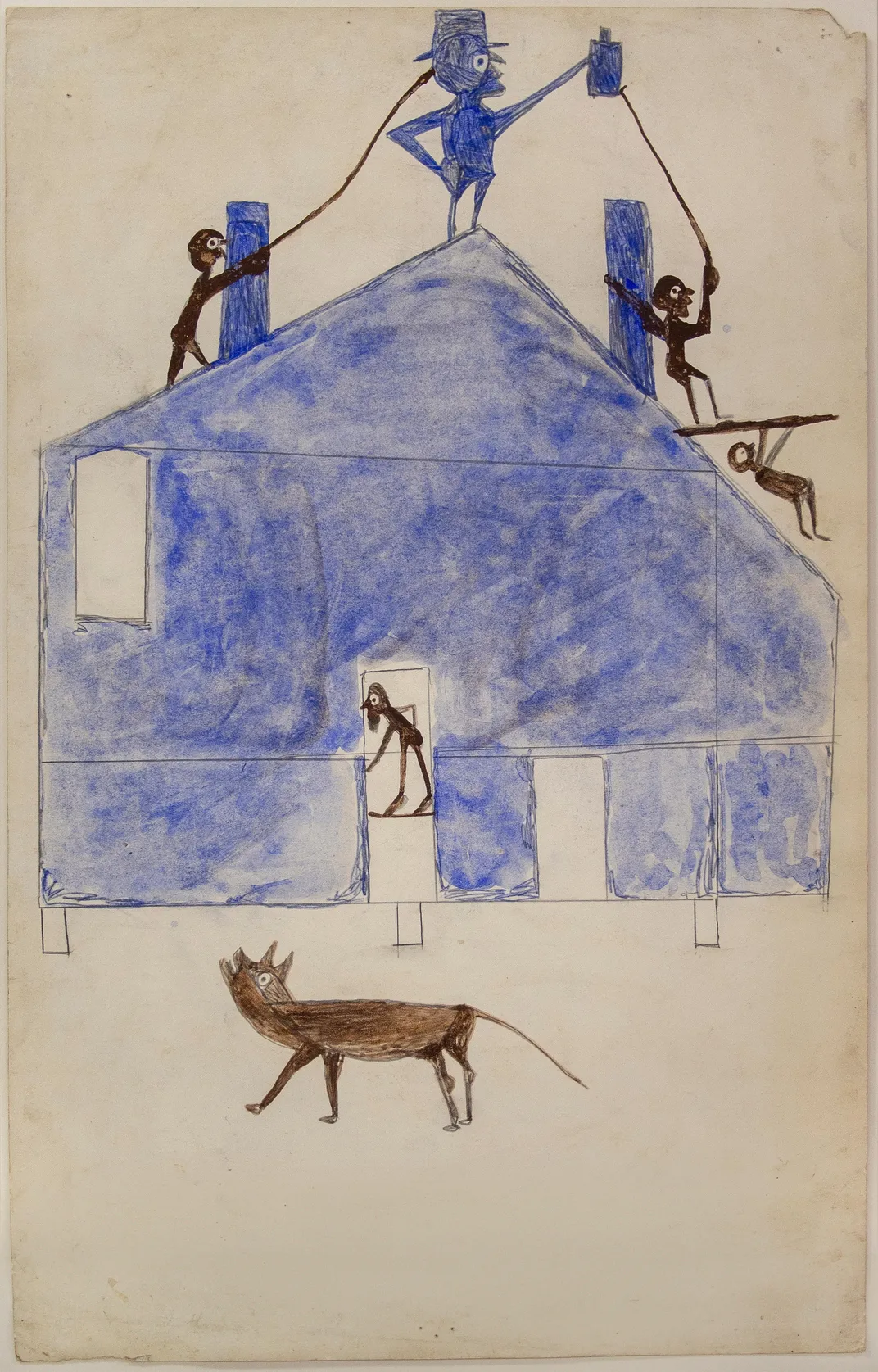

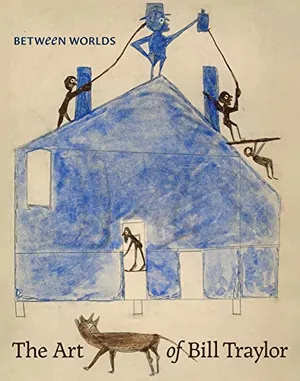

Now, nearly 70 years after his death in 1949 at about age 96, 155 drawings and paintings have been brought together for the biggest retrospective of his work to date, “Between Worlds: The Art of Bill Traylor” at the Smithsonian American Art Museum in Washington, D.C.

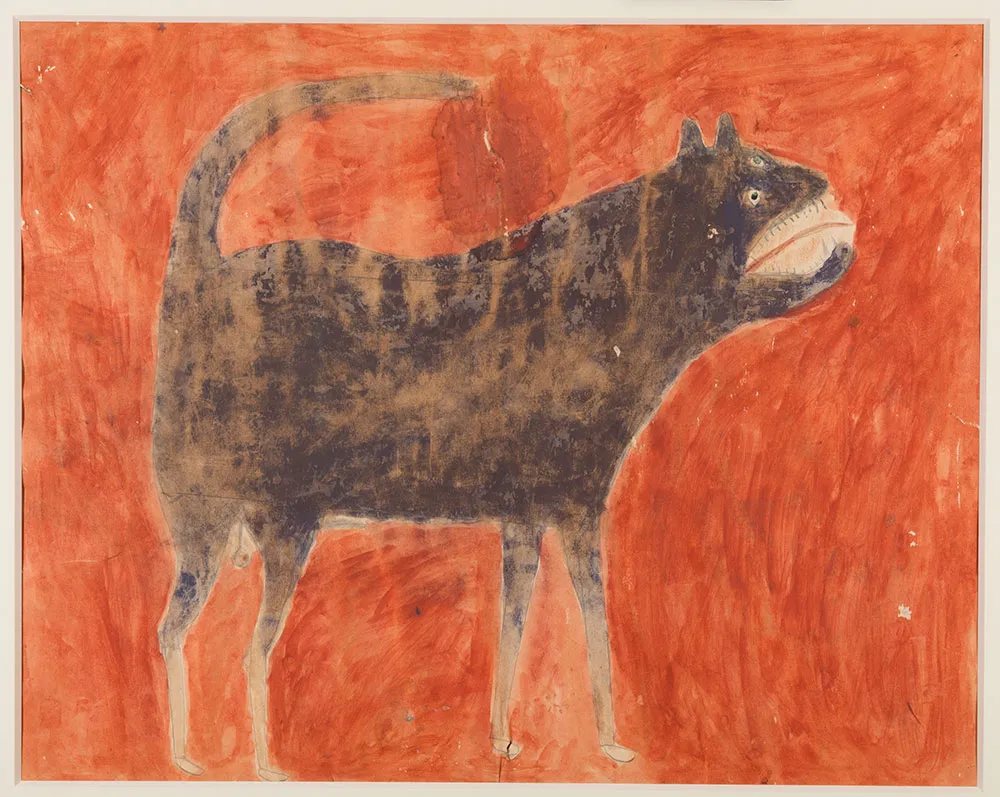

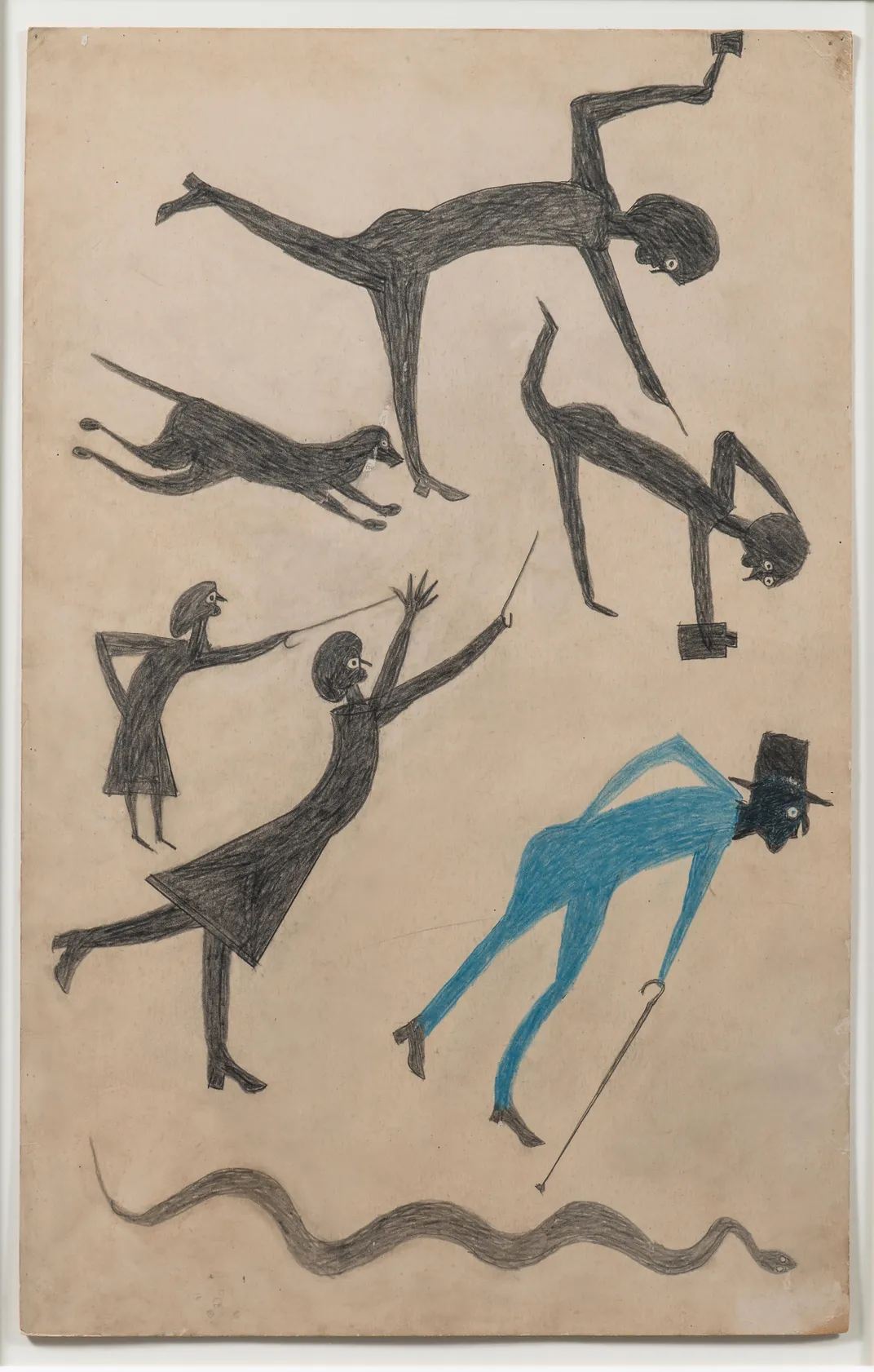

The arresting images of barking dogs, farm and city scenes, made from 1939 to 1942, also hint at a lifetime of hardships and division. Though illiterate, Traylor was able to convey generations of African-American history through his images. The extensive exhibition, accompanied by a comprehensive 444-page monograph on Traylor’s life and art, are the result of seven years of extensive scholarship by Leslie Umberger, curator of folk and self-taught art at the museum.

Umberger’s research, she says, was part detective work, part treasure hunt. “The record of his life is not concrete,” she says. Even his date of birth is a guess. But everything in the exhibition and the book are “to the best of our knowledge, based on a lot of original research.”

The lifespan of Traylor almost perfectly splits the 19th and 20th century. But the exhibition is titled “Between Worlds” for other reasons. “He’s always looking back and forth between rural and urban, old and new, and very importantly, between black and white worlds,” Umberger says. His life is an example of “always having to know how to live and get along in the white world, but also be a part of the black world, and knowing how to navigate those differences in order to simply survive.”

While there were other artists in the field in the time Traylor was making art, she says, “the more I studied the field as a whole I realized that nobody was born as early as he was.” Traylor is the only known person born enslaved and entirely self-taught to create such an extensive body of graphic work. Even so, very little of his work after 1942 survives.

Depicting the street life of Montgomery, where he went to live after spending most of his life on plantations, he only rarely overtly portrayed racial strife. The sheer violence of the antebellum South and all that came after can be seen reflected in the number of fighting dogs in his works; the danger exemplified by the snakes depicted throughout. In one work, a black man argues with a white woman. In another, what was long described as a possum hunt, now looks more clearly like a group is hunting a human.

“The art can sometimes look very simple,” Umberger says. But in his art, “Bill Traylor sent two messages: one to the African-American people in the segregated neighborhood where he was living and made them, and another to any of the white people that might be looking at what he’s doing.”

To be any more overt would be risky. “For an elderly black person in segregated Montgomery,” she says, “the very act of making these art works was really taking his life into his own hands, especially if he decided he was going to express a point of view that could be seen as confrontational.”

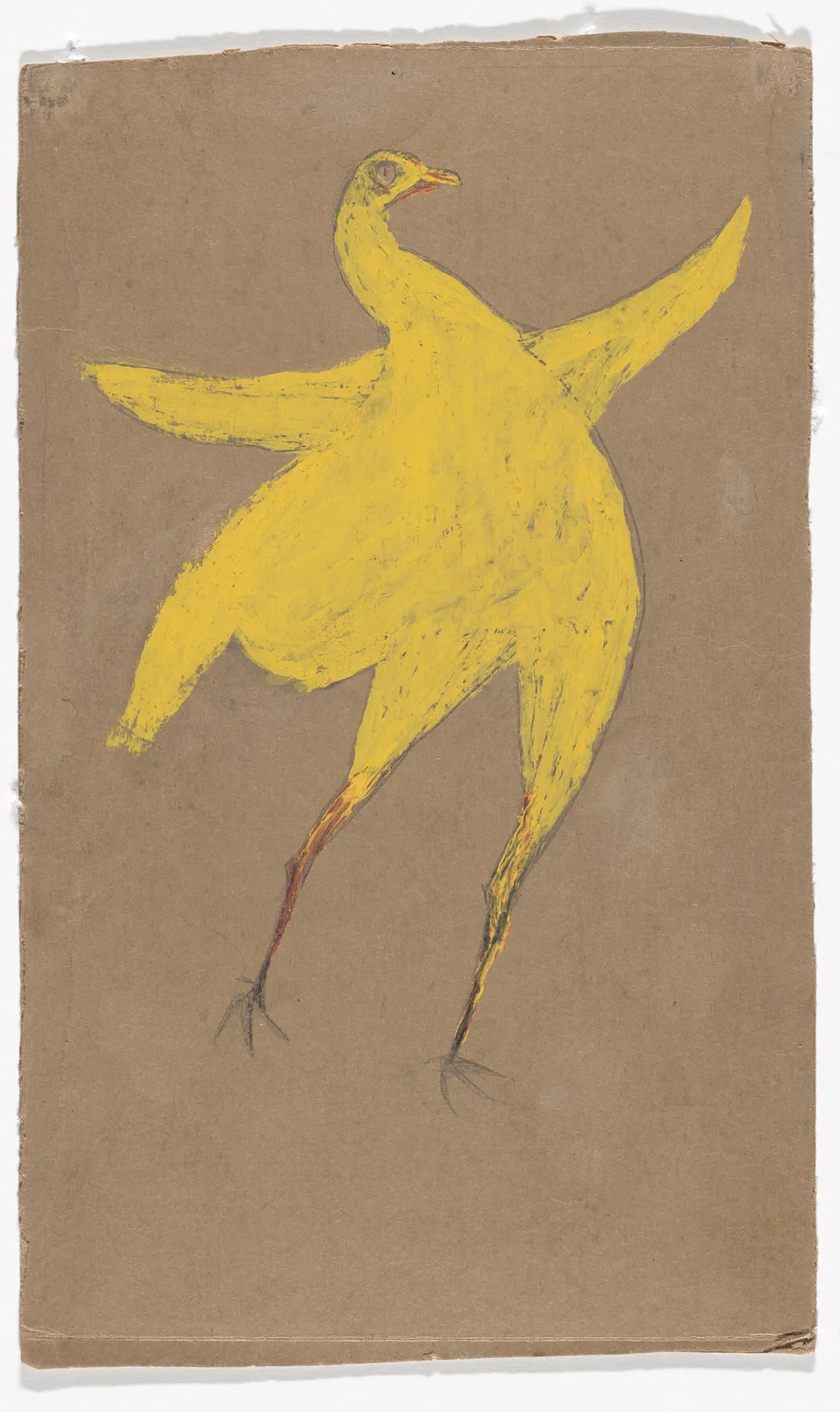

So allegory takes over—his portraits of rabbits are often interpreted as runways; birds represent freedom. Traylor himself only gave a few terse comments about his work that were written down by the artist-collectors in town who supplied him with the cardboard he used. So his intent was not always clear.

Between Worlds: The Art of Bill Traylor

Between Worlds presents an unparalleled look at the work of this enigmatic and dazzling, Bill Traylor (ca. 1853–1949), who blended common imagery with arcane symbolism, narration with abstraction, and personal vision with the beliefs and folkways of his time.

“That’s a real monumental task, when an artist wasn’t able to speak for himself,” Umberger says. “It’s something I think about a lot when I put an exhibition together: How do we speak on behalf of those who don’t have an opportunity to tell their own story, except through these pictures.” Ultimately, she presents the work while trying to “give the richest backdrop of that person’s life that you can—tell everything you can possibly flesh out so the backdrop brings that story to life.”

But sometimes the designs themselves, that can burst into exuberant lifelike Matisse cutouts, are expression enough to draw fans worldwide. “I saw a Bill Traylor piece at the Whitney Museum a couple years ago. Ever since, I just went crazy about him,” says Edmar Neto, a 33-year-old folk art collector from Sâo Paulo, Brazil.

When he heard of the Smithsonian exhibition, he jumped on a plane. “It’s amazing to see how he’s inserted in the big museum’s collections,” Neto says. Usually art categorized as folk or untrained gets its own compartment. But now, “you get to see how he’s the real modern artist, how he makes synthesis of what’s going on and shows the world through his eyes.”

The exhibition’s only showing is appropriately in a building that dates to Traylor's era. The museum is housed in one of the oldest structures in Washington, D.C., which served as a Civil War hospital and was the site of Lincoln’s second inaugural ball.

The exhibition “exponentially expands not just the story of one self-taught artist,” says the museum’s director Stephanie Stebich, “but also the overarching stories of American and African-American art in the 20th century.”

Knowledge of Traylor is growing. In March 2018, family and community members, along with scholars and other supporters of Traylor's work gathered at the unveiling of a proper headstone for his previously unmarked grave in Montgomery, Alabama. Concurrent with the planning of the show, documentarian Jeffrey Wolf made a film about the artist—Bill Traylor: Chasing Ghosts had its premiere the weekend the exhibition opened.

“My movie I think is about ancestry, history, authenticity, poetry, performance and embracing a responsibility for the past and applying it to the present,” Wolf says. In brief remarks at a September screening of the film, he quoted The Warmth of Other Suns author Isabel Wilkerson about the era in which Traylor lived.

“On all those cotton fields, and those rice plantations and tobacco fields there are opera singers and jazz musicians and poets and professors, defense attorneys, doctors and artists,” she says. “This is the manifestation of the desire to be free and what was lost to the country.”

“Between Worlds: The Art of Bill Traylor,”curated by Leslie Umberger with assistance from Stacy Mince, continues through April 7, 2019 at the Smithsonian American Art Museum in Washington, D.C.

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/RogerCatlin_thumbnail.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/42/ae/42ae665b-151a-4255-a059-ef876a714f74/dog_fight_with_writing.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/bc/64/bc640d45-5ab4-4990-acdc-31168b6e495e/man_with_yoke.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/77/05/77055a62-260c-486e-ad52-544364bdadf0/yellow_and_blue_house_with_figures_and_dog.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/RogerCatlin_thumbnail.png)