Birds Collected Nearly Two Centuries Ago Still Help Scientists Today

The specimens gathered during an illustrious expedition by naturalist John Kirk Townsend continue to provide value to researchers

:focal(3413x1695:3414x1696)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/2c/a3/2ca36e4d-21a9-45f2-a303-a4d7959d9aa5/julaug2021_a03_prologue.jpg)

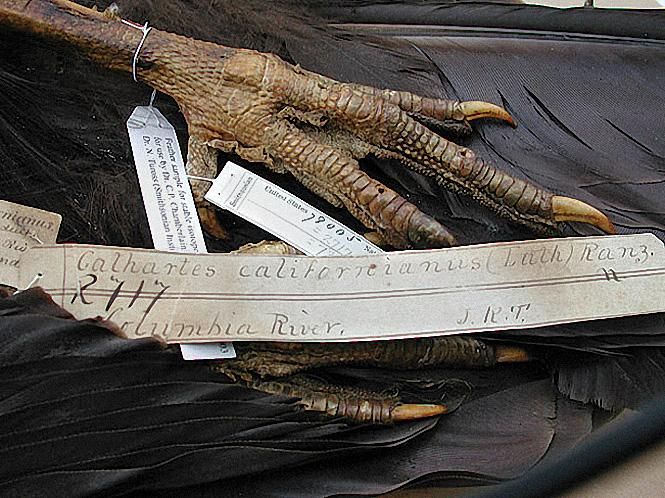

In May 1835 in Willamette Falls, Oregon, an eager young Philadelphia naturalist named John Kirk Townsend collected a female California condor. It’s one of the oldest specimens among the Smithsonian’s 625,000 preserved bird skins, the third-largest collection in the world. A bouquet of tags attached to the condor’s legs, along with the original label in Townsend’s copperplate handwriting, shows it has become only more valuable to science over the decades.

Every natural specimen is full of information about the time and place from which it came, but it also suggests a story about the people who discovered or collected it. Townsend’s condor, as well as more than 130 other bird specimens that he prepared and that are kept at the National Museum of Natural History, are part of a little-known American story of curiosity, bravery, wanderlust, bias and even tragedy.

Townsend was born into an intellectual Philadelphia Quaker family in 1809, and developed an early passion for birds. In 1833, in nearby Chester County, the young man shot and stuffed a finchlike bird that he couldn’t identify; John James Audubon, to whom he showed the skin, believed it to be a new species and named it “Townsend’s bunting” and included a painting of it in his Birds of America.

The following year, Townsend was invited by the British-born botanist Thomas Nuttall, with whom he was already well acquainted, to join him on Capt. Nathaniel Wyeth’s expedition to the Pacific Northwest to establish a trading post. With Wyeth’s 70-man crew, they ascended the Platte River alongside what would later become the Oregon Trail, crossing the Rockies to the Columbia River. Along the way, Townsend confronted grizzly bears, tested the theory that a bull bison’s skull was thick enough to deflect a rifle ball at close range (it was) and lost an owl he’d collected for science when his companions, short on food, cooked it for supper.

Townsend and Nuttall spent about three months near the mouth of the Columbia before sailing to Hawaii for the winter and returning to the Northwest coast for a second summer. Nuttall went home that fall, but Townsend spent another year there before sailing back to Philadelphia in 1837. Townsend published a lively account of his travels, A Narrative Journey Across the Rocky Mountains, to the Columbia River, and a Visit to the Sandwich Islands, Chili &c. But he didn’t get scientific credit for all the new bird and mammal species he’d collected. For instance, some of his duplicate specimens ended up with Audubon, who rushed to describe them in print and received credit for the discoveries. Still, two birds and seven mammals, including a jack rabbit, a mole and a bat, carry his name. He died in 1851 at age 41, his death blamed on exposure to the arsenic he used to protect his specimens from insects.

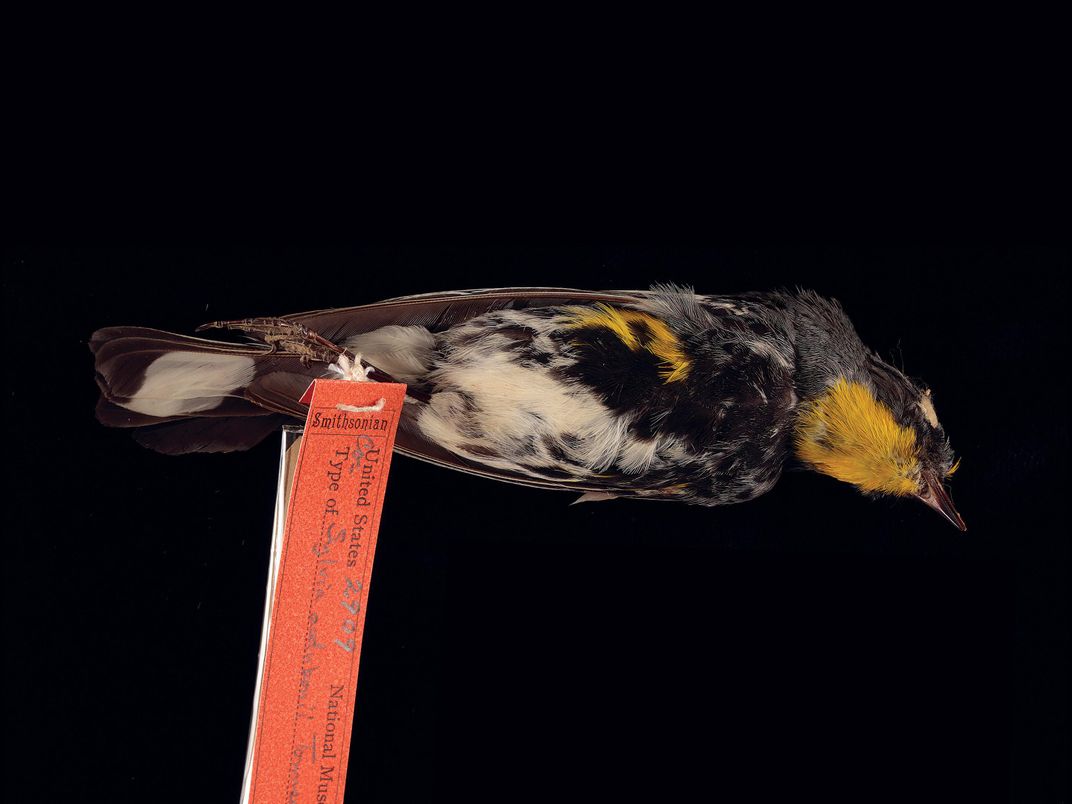

Townsend’s collection came to the Smithsonian in 1858 with other material from the National Institute for the Promotion of Science, a short-lived private museum in Washington, D.C. where Townsend himself briefly served as a curator. The specimens include the one and only Townsend’s bunting. “It’s in terrible shape, unfortunately,” says Christopher Milensky, collections manager of the Smithsonian’s Division of Birds. In the nearly 190 years since Townsend collected it, the mystery bird has been sighted just once more—in Ontario in 2014—and ornithologists debate whether it’s actually a dickcissel with aberrant plumage or a hybrid. (Milensky says a planned genetic test of the skin may answer the question.)

The Townsend specimens have great scientific value. Tiny bits of tissue from the condor skin, for example, have provided insights into the original genetic makeup of the California condor population. By analyzing chemical isotopes in its feathers, researchers found that it fed heavily on stranded marine mammals and salmon, much as Townsend had observed. Each time a rice-grain-size bit of toe pad, or a small feather, is removed for analysis, Milensky says, curators add a separate leg tag to record the action. The condor now has at least six.

Another legacy of the Townsend birds is a set of more than two dozen type specimens—the individuals from which new species or subspecies were first described for science. That includes a species called Townsend’s warbler, which he collected along the Columbia River.

How much longer Townsend will be able to claim his warbler, though, is unclear. The ornithology community has been wrestling with the propriety of maintaining honorific bird names, given the actions of many of the people—overwhelmingly white men—for whom the birds were named. Audubon, for example, was a slave owner. Last July, the American Ornithological Society, the official arbiter of English bird names in the Western Hemisphere, changed the name of McCown’s longspur to “thick-billed longspur” because John P. McCown, who collected the first scientific specimen in 1851, later served as a Confederate general. A movement among American birders and ornithologists, under the banner “Bird Names for Birds,” is arguing to do away with dozens of honorifics, replacing them with descriptive names.

Townsend, for his part, has recently come in for criticism because he robbed indigenous graves in the Pacific Northwest and sent eight human skulls to Samuel Morton, of Philadelphia, who used them to bolster his obnoxious views about race.

Yet, even if Townsend’s warbler officially becomes, say, the “fir-forest warbler,” its skin, and the others he collected nearly two centuries ago, will have secrets to share for years to come.