The Bitter Aftertaste of Prohibition in American History

Anti-immigration sentiment flavored that cocktail ban, historians say

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/b0/3d/b03d11e1-7c24-498a-995d-b48ec40e2e54/pro-105_01094419.jpg)

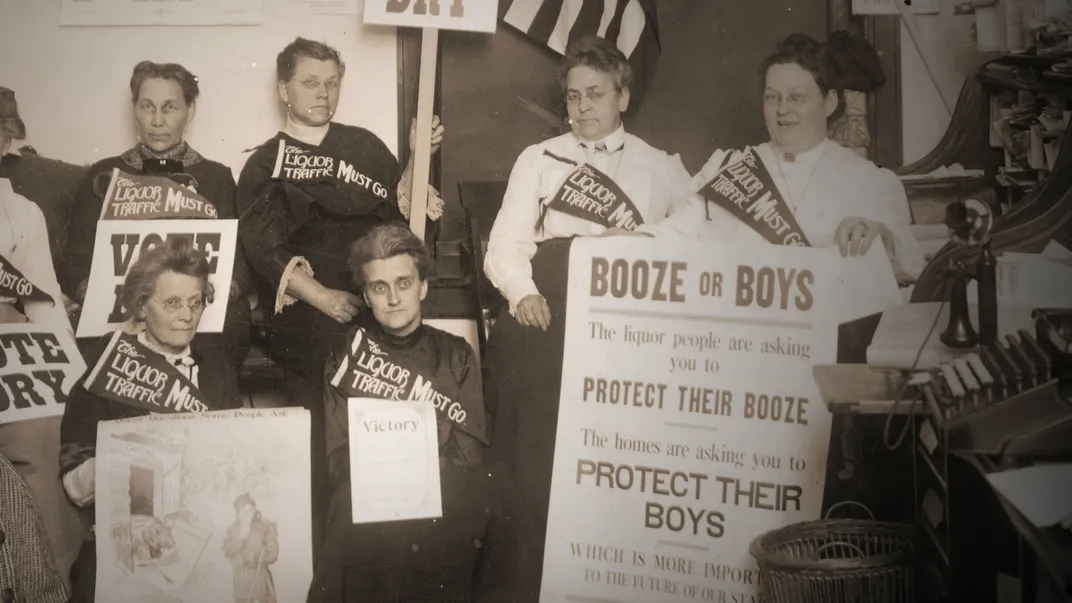

For many, Prohibition recalls a freewheeling era in American history with speakeasies, bootlegging, gangsters and G-men. But new scholarship shows that several factors beyond the obvious underlay the 1920 ban on the manufacture and sale of intoxicating beverages.

“They’re fighting over alcohol, but they’re also fighting over immigration and identity in the country,” says Jon Grinspan, a curator of political history at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History, who appears in the new two-part Smithsonian Channel documentary miniseries on the era, “Drinks, Crime and Prohibition.”

The American push to ban alcohol for health and moral reasons had been growing since the days of the temperance movement in the mid-19th century. While individual states and localities went dry, it wasn’t until 1917 that Congress passed a resolution to submit a constitutional amendment for a ban that was sent to the states for ratification. Thirty-six states needed to ratify, and in 1919 they did. Prohibition officially began the following year, bringing with it a number of changes to the country, from the rise of organized crime to the concomitant increase in federal policing.

But, as Grinspan says in the documentary, “alcohol is not the central story of Prohibition. There are people who are fighting alcohol, but what they are fighting about is a clash of two civilizations in America.”

The enemy is not just alcohol, but European immigrants, the documentary argues. Between 1892 and 1920 almost 12 million immigrants entered the U.S. through Ellis Island.

“Organizing around alcohol is in some ways a politically correct way to go after other immigrants,” Grinspan says in the documentary. “It’s not entirely polite to say, ‘I want to get all of the Catholics out of America.’ But it’s very polite to say, ‘Alcohol is ruining society.’”

“That’s one of the big changes in recent scholarship,” says Peter Liebhold, a curator in the division of work and industry at the American History Museum, who is also featured in the series. “A lot of people are looking at the success of the temperance movement as an anti-immigrant experience. It becomes code for keeping immigrants in their place.”

Grinspan is first seen in the series displaying a cast iron axe meant to poke fun at longtime temperance leader Carrie Nation, known for attacking barrooms with a hatchet. Once hung prominently in a bar, this axe bears the text “All Nations Welcome But Carrie.”

When it comes to saloons in America, Grinspan says, “we have this misconception that they’re broken up by ethnicity and Irish people only drank with Irish people and German people only drank with German people. But there’s a great deal of mixing, especially by the 1910s of these populations.”

Slogans like “All Nations Welcome but Carrie,” he says, were “making an argument both against prohibition and for a kind of diversity within their community that the people who are opposed to alcohol and supporting prohibition are coming after.”

Indeed, part of the reason Prohibition passed was that it elicited unusual alliances—organized women who would go on to fight for suffrage worked alongside anti-immigrant hate groups as well as industrialists who didn’t like how saloons were causing drunkenness among their workers and becoming centers of power for unions and political parties.

“The idea that suffragists—women’s rights advocates—and the Ku Klux Klan, for instance, are fighting on the same side of this thing,” Grinspan says, “is really unusual.”

“Very strange bedfellows,” agrees Liebhold. Once Prohibition was enacted, the Klan even took on its enforcement, historians say. But the coalition of different interests was successful because “they tried to stay on target of only being against alcohol consumption—and not getting snared into other issues that will break those coalitions apart,” Liebhold says. “Politically, they’re pretty astute.”

Wayne Wheeler of the Anti-Saloon League is credited with combining the power of the various groups and making the movement a success where it had not been before.

Many influential backers of the cause were industrialists, who were at war with a fledgling labor movement dominated by immigrants, the film says. And the saloons, Grinspan says, “are centers of power.” At the time, there were 200,000 saloons across America—“which is 23 saloons for every Starbucks franchise there is today,” Grinspan says. “So, when World War I breaks out and there are signs for German beer all across the country in people’s communities, it’s such an obvious target.”

Liebhold says the anti-Prohibition forces were disorganized in part because the spirit distillers didn’t really work with the brewers.

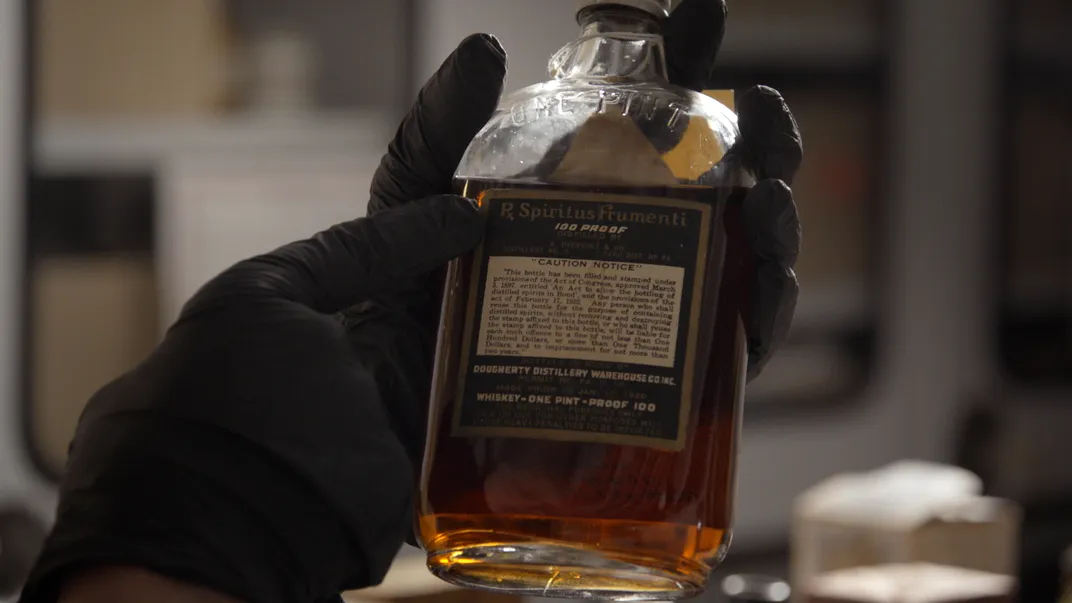

Once the states voted, approval of what became the 18th Amendment came fast, Liebhold says. “I think some people were surprised how quickly that all came about.” Suddenly, saloons, breweries and distilleries—all well-established across the country—became criminal enterprises. Crime networks grew to accommodate their old customers. And the federal response grew alongside them.

“It really empowers the federal government,” Grinspan says. “People used to see Prohibition as this one-off, weird era that didn’t really fit in with what else was going on.” But it really gave rise to vastly expanded federal law enforcement powers, he says.

“Federal prisons are a tiny portion of prisoners before Prohibition,” Grinspan says. “With the enforcement of Prohibition, the FBI, the prison system, the Department of Justice—all of these things expand greatly in the process.”

The initial Bureau of Prohibition was established in 1920 as the first national policing force. Because it was organized outside the civil service, though, it was susceptible to corruption, the documentary says.

When a Seattle police lieutenant was arrested as a bootlegger after his phone was tapped, the U.S. Supreme Court decided in 1928 it wasn’t a violation of the Fourth Amendment rights related to unreasonable search and seizure—a landmark decision that led to other laws dealing with securing information from private citizens. The dissent of Justice Louis D. Brandeis was just as influential, as it cited a constitutional “right to be let alone”—words used in the Roe v. Wade decision 45 years later.

“You see this fundamental change in the government in that it starts controlling the lives of its citizens, telling them what they can and cannot do—and it’s punitive,” Liebhold says.

And suddenly, everyday people find themselves, when taking the occasional nip, lawbreakers. “Prohibition was widely flaunted by people from all walks of life,” he says. “It’s never good to have a rule nobody believes in because it takes away from the power of other laws that are important.”

In time, industrialists changed their minds on Prohibition, finding their workers were no less drunk at work than before. Additionally, losses in alcohol excise taxes had to be made up with income taxes. By 1933, it was clear the crackdown wasn’t having the desired effects, and the ratification of the 21st Amendment did away with the Prohibition.

“Everybody was amazed at how quickly it disappeared,” Liebhold says of the 13-year-long era. “It was like a bizarre alignment of the stars and it was gone. And it never happened again. This is the only Constitutional amendment that’s ever been repealed.”

But the effects of Prohibition linger—and not only in organized crime and movies about the Al Capone era, or in the clever cocktails invented by period scofflaws (the documentary provides recipes for several of them).

Modern-day arguments about the legalization of marijuana are only the most obvious echoes of Prohibition, Liebhold says, adding, “I think the parallels today on so many issues are really incredible.”

“Drinks, Crime and Prohibition” airs on the Smithsonian Channel June 11 and 18 at 8 p.m. EDT/PDT.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/RogerCatlin_thumbnail.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/RogerCatlin_thumbnail.png)