The Bizarre Tale of the Tunnels, Trysts and Taxa of a Smithsonian Entomologist

A new book details the sensational exploits of Harrison G. Dyar, Jr., a scientist who had two wives and liked to dig tunnels

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/bf/f4/bff42887-b84b-4d04-8c5f-fd88f654745e/26186u.jpg)

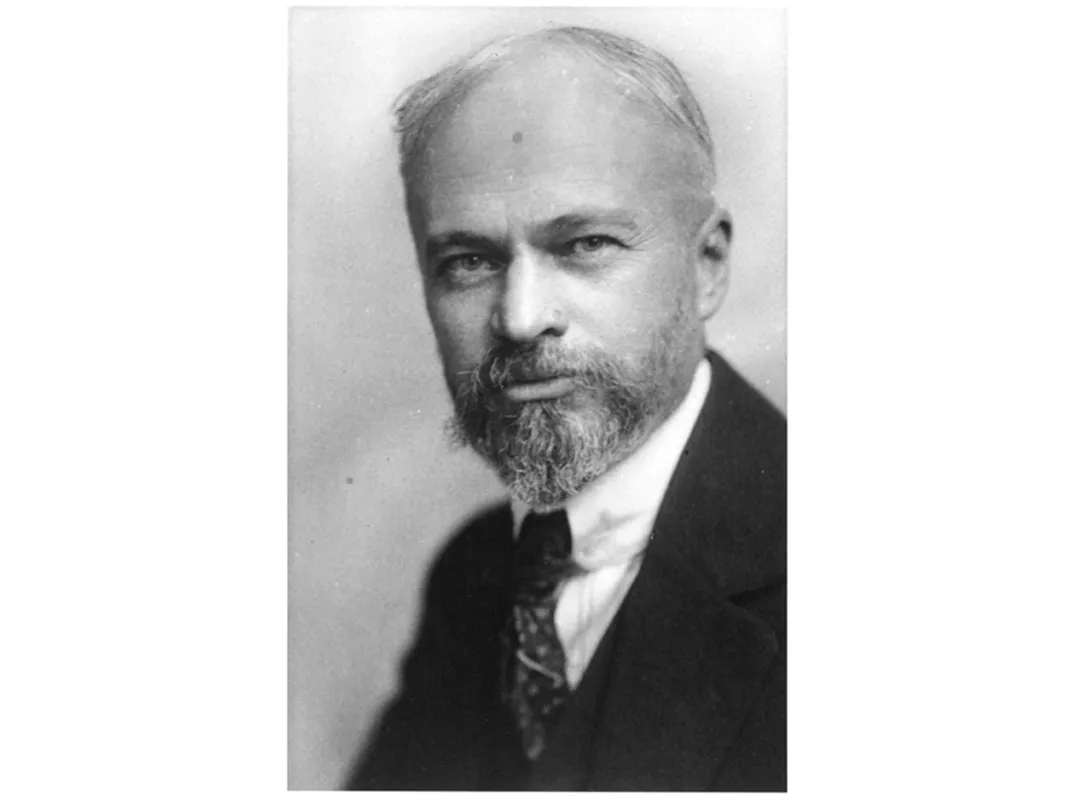

Among America’s pantheon of scientific innovators, few have led lives as notable as that of Harrison G. Dyar, Jr. (1866-1929), an outré entomologist whose personality was as colorful as the caterpillars he studied.

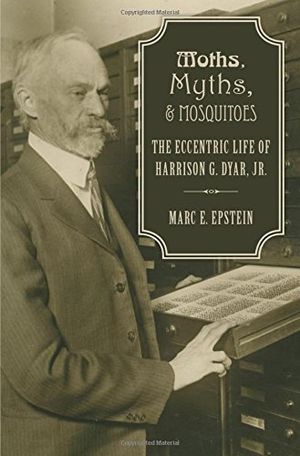

The subject of scientist-turned-biographer Marc Epstein’s recent book, Moths, Myths, and Mosquitoes: The Eccentric Life of Harrison G. Dyar, Jr., is remembered not only for prodigious productivity in his field of research, but also for his oddly exotic avocations.

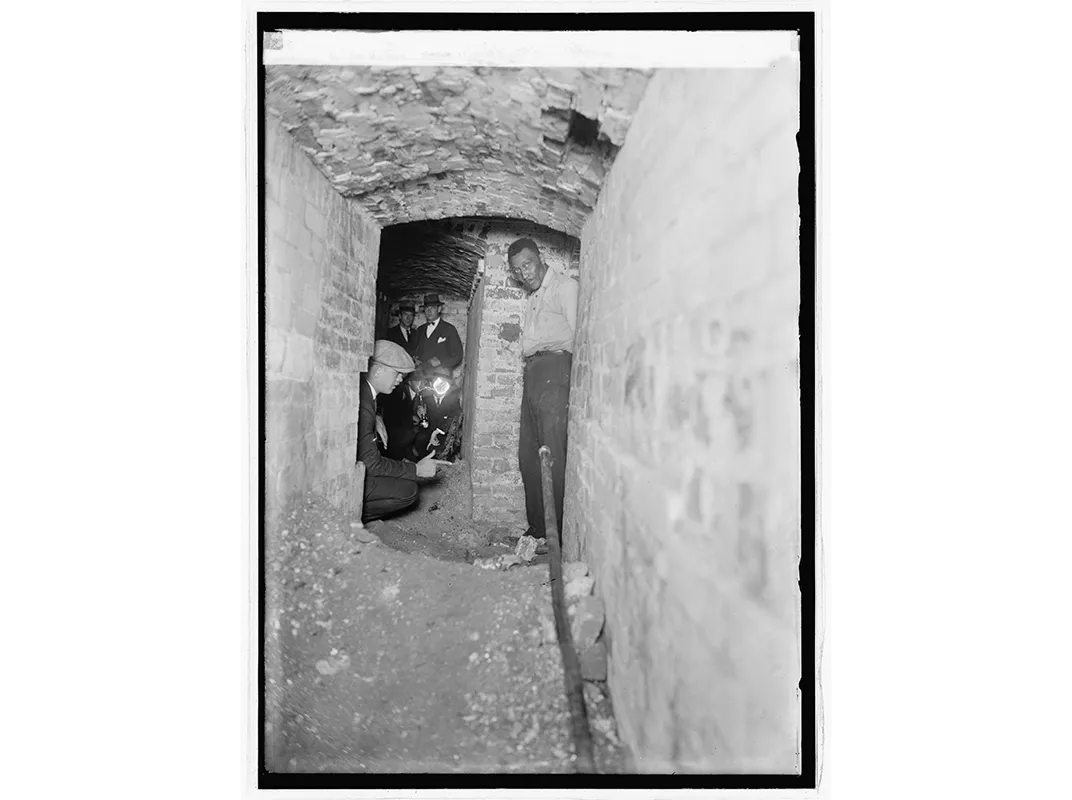

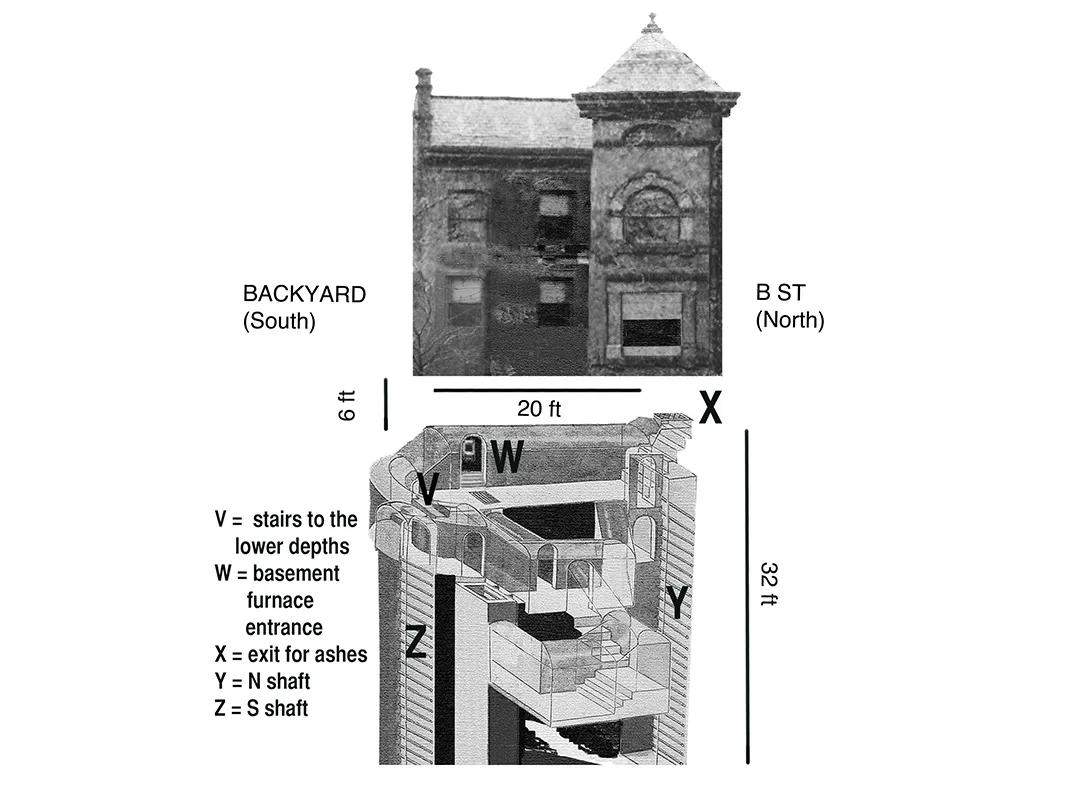

Dyar instigated fiery feuds with his fellow entomologists. He was concurrently married to two different women. And he dug elaborate, electric-lit tunnels beneath two of his D.C. residences, disposing of the dirt in a vacant lot, or else passing it off as furnace dust or fertilizer.

Long after his death, there were whispers that the tunnels had enabled him to shuttle between his lovers—an urban legend that, while apocryphal, speaks to the mystery in which Dyar seems perennially shrouded.

Epstein, a specialist in Lepidoptera (moths and butterflies) at California’s Department of Food and Agriculture and a Research Associate in association with the Smithsonian’s Department of Entomology, aimed to address as many of Dyar’s disparate facets as he could in his new book—“the whole enchilada,” he says.

This proved to be quite the challenge. “You could choose just one aspect and easily write a book the size [of mine],” he adds. Epstein’s holistic approach to the Dyar narrative spawned an incredible piece of nonfiction.

Dyar—the offspring of an inventor whose work in telegraphy nearly beat Samuel Morse to the punch and a spiritualist whose sister supposedly co-hosted a séance attended by no less than President Abraham Lincoln—was fated from birth to lead a sui generis life. Throughout his long and meandering career, the bug boffin’s exploits would win him as many enemies as they would admirers.

It cannot be denied that Dyar’s contribution to the field of entomology was staggering. Over the course of his eventful existence, the Gotham-born scientist named some 3,000 insect species, and compiled a hefty catalog enumerating 6,000 varieties of lepidopterans. He also pioneered in work on sawflies and mosquitoes, the latter a source of serious concern to those overseeing the construction of the Panama Canal, and in 1917 donated 44,000 miscellaneous insect specimens to the Smithsonian Institution. As Epstein aptly puts it: “Everything he did was in the hundreds or thousands.”

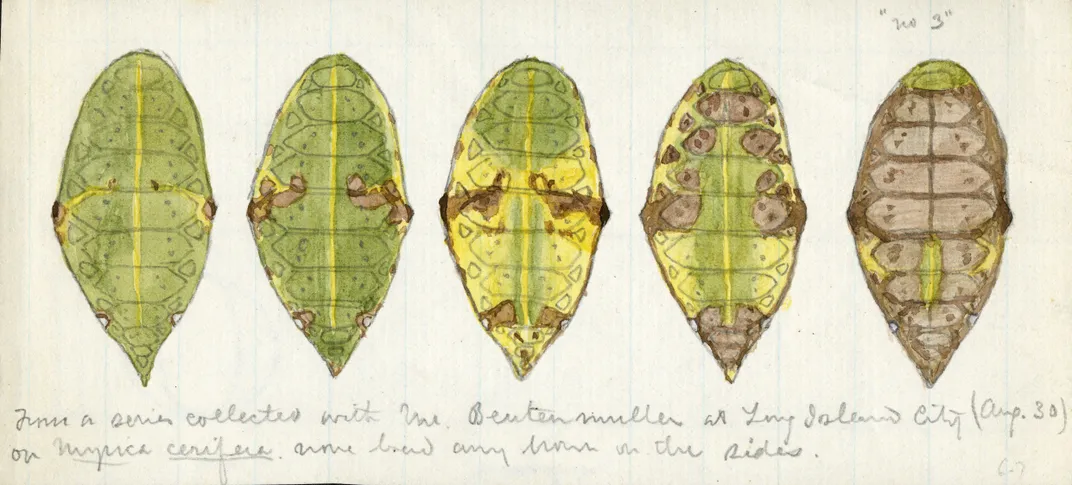

Fastidious in the extreme, Dyar captured, bred and reared the creatures he studied in droves; his essays furthered the understanding of the elusive role of larval stages in taxonomic classification.

Dyar’s Law, a principle invoking head size in larvae as a predictor of the number and nature of stages (instars) in insects’ full life cycles, is in wide use to this day, applicable in what the literature has shown to be 80 percent of instances.

One cause of Dyar’s punctiliousness, Epstein posits, was his deep-seated compulsivity.

Manifest in Dyar’s ceaseless collection efforts (including a transcontinental “honeymoon” trip with his wife Zella), prolific note-taking (often on the backs of grocery receipts, bills of sale and letters), and arcane cross-referencing (Dyar’s writings are coded with scores of mysterious symbols), this trait, which served him well in his scientific pursuits, did little to endear him to his peers and loved ones.

While conducting research at the National Museum, for instance, Dyar complained bitterly about the bureaucratic organization of the Smithsonian Institution, and resented delays in the publication of his scientific findings. In 1913, seeking to obviate these roadblocks, Dyar founded his very own entomology journal, which he titled Insecutor Inscitiae Menstruus—“persecutor of ignorance monthly.”

Dyar also picked nasty personal fights. So vituperative were his criticisms of fellow entomologist J.B. Smith, and so tactless his pooh-poohing of Smith’s late colleague and friend, Rev. George Hulst, that Smith ultimately swore “to have no further relations with the National Museum so long as Dyar remained.”

If Dyar’s professional life was rocky, his private one was rockier.

In the early years of the 20th century, Zella Dyar, who in 1888 had won Harrison’s affections by sending him Lepidoptera specimens from Southern California, became increasingly aware of her husband’s fondness for another woman—Wellesca Pollock.

The fair and auburn-haired Pollock was a kindergarten teacher whom Harrison had met— and to whom he had taken quite a fancy—during a Chautauqua excursion in the Blue Ridge Mountains in 1900. Dyar had named a member of the family Limacodidae (one of his “pet” Lepidoptera groups) after her that November (Parasa wellesca), and his visits to her place of residence had grown more and more regular in the years following.

The situation took a bizarre turn when Wellesca announced her 1906 marriage to Wilfred P. Allen, a fellow whom no one ever saw but who fathered three children of hers over the next decade.

Zella, alarmed by the dubious identity of Wellesca’s partner, especially in light of her own husband’s increasingly lengthy periods of absence from home, wrote desperate letters to her. Wellesca responded reassuringly, stating that whatever she felt for Dyar was purely “sisterly” in nature.

Years after this epistolary exchange (and others that followed), Harrison Dyar moved to secure a quick, low-profile divorce from Zella. Once she became aware of the lurid details of her husband’s relationship with Wellesca, however, the possibility of such a tidy split evaporated.

Wellesca’s hush-hush attempt to obtain a divorce from her own “husband” was stymied as well, albeit for a different reason. “Unconvinced of Allen’s existence,” Epstein recounts, “the judge ruled that Wellesca was unable to divorce him.”

The messy resolution of this debacle, which eventually saw Harrison and Wellesca officially united at severe professional cost to the former, is but one of the many intriguing threads traced in Epstein’s book.

The various stressors in Dyar’s life may well have fueled the creation of the labyrinthine tunnel networks found beneath two of his D.C. properties (one in Dupont Circle, the other just south of the National Mall), in which his own children were sometimes apt to play, and in which a 1924 Washington Post exposé postulated that “Teuton war spies” and “bootleggers” had once fraternized. The digging, which Dyar himself wrote off as little more than a physical workout, was, in Epstein’s view, a form of “Dyarian absolution”—a way for the scientist to battle his inner demons.

Research into the scientific findings of Dyar, as well as the juicy minutiae of his tortuous life, proceeds apace to this day. With no shortage of notebooks, scratch paper, and unpublished short stories (many of them autobiographical) to peruse, archival Dyar investigators have their work cut out for them.

Spearheaded by Epstein, the Smithsonian’s own ongoing efforts at transcription, decryption, and data base compilation promise boons not only for the entomological community, but for everyday citizens, each of whom stands to learn much from the fascinating story of one of America’s lesser-known scientific stars.

Marc Epstein will speak on the vibrant life of Harrison G. Dyar, Jr. from 6:45-8:15 PM on Tuesday, May 17. The Smithsonian Associates event, for which tickets are now available online, will take place at the Smithsonian’s S. Dillon Ripley Center.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/DSC_02399_copy.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/DSC_02399_copy.jpg)