For Black Photographers, the Camera Records Stories of Joy and Struggle

The African American History Museum showcases for the first time signature photographs from its new collections

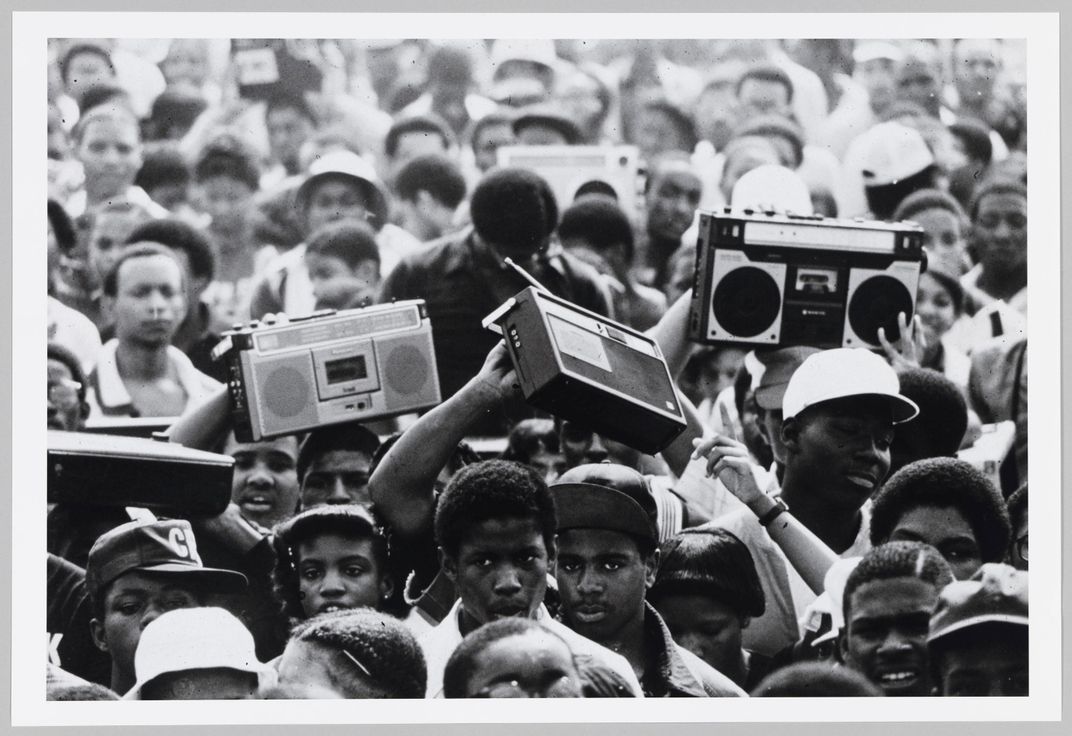

In 1982, Sharon Farmer hit the streets of Southeast Washington, D.C.’s Anacostia, camera gear in tow. It was Anacostia Park Community Day and people were blasting go-go music from boom boxes they held above their heads. Elated to see the neighborhood where she grew up buzzing with excitement, she snapped an iconic photo.

The black and white image shows a commanding scene of the power of community and the energy of the young people; the packed crowd radiates toward the viewer. “It just rocked my socks,” says Farmer, who, when she was hired by the Clinton administration, was the first African-American woman to work as an official White House photographer. Now, she wonders where these young people are today. “Did anyone turn into an artist?,” she muses as she studies the photograph now hanging at the National Museum of African American History and Culture.

Her photograph is one of 169 images showcased in the museum’s first special exhibition, “More Than a Picture.” Opening almost exactly one year after staff began installing artifacts in the Smithsonian’s newest museum, this exhibition is just a taste of its massive photography collection, which includes more than 25,000 images.

“Photographs are meaningful. They are stories. They are memories,” says curator Michèle Gates Moresi. “They are the visual connection to our past as much as to our present and our future generations.”

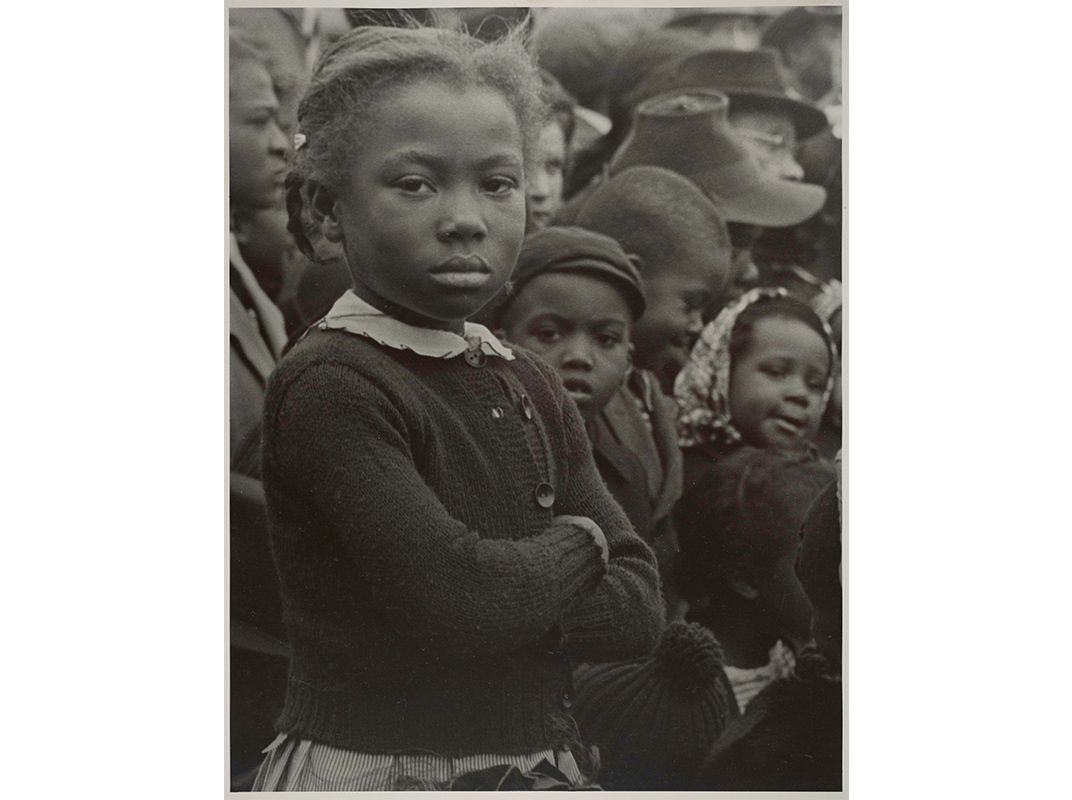

The exhibition follows in the spirit of a show created by African-American author and activist W.E.B. Du Bois for the 1900 Paris Exposition entitled “American Negro Exhibit,” which aimed to tell the story of post-slavery black America through photography. With thoughtful labels that explain context and history, the show seeks to examine the many corners of African-American life from slavery to now. “There is joy and there is struggle,” says museum director Lonnie Bunch of the exhibition’s scope.

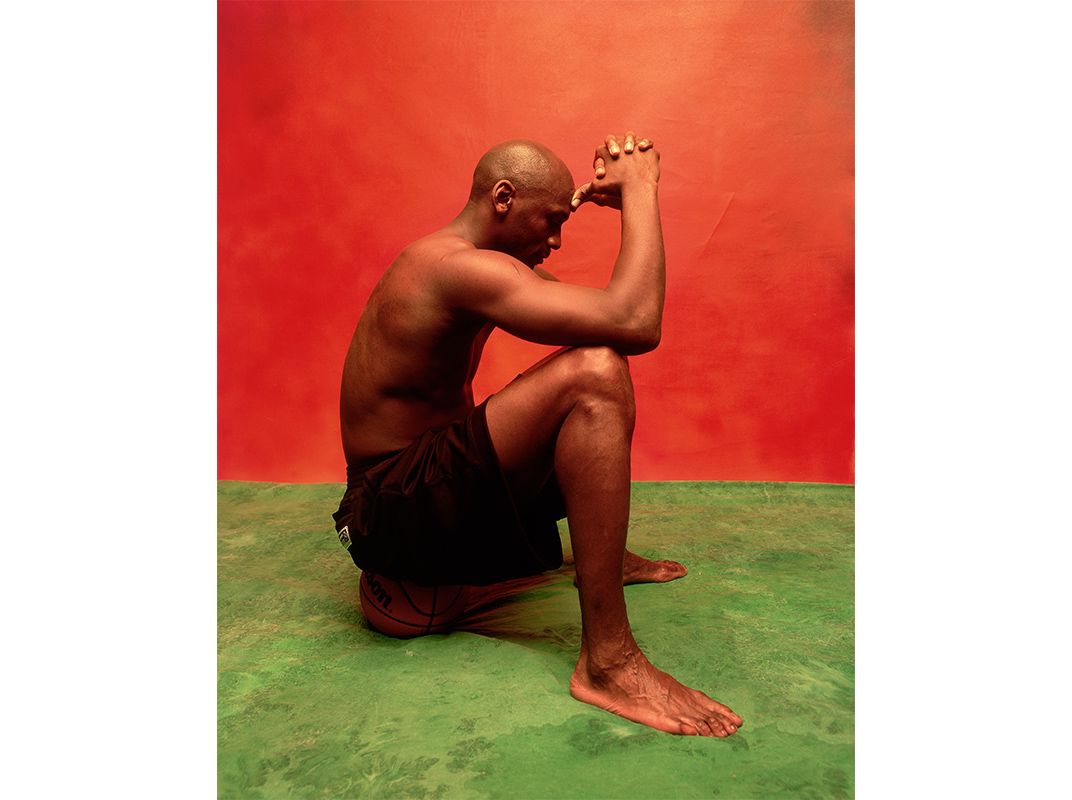

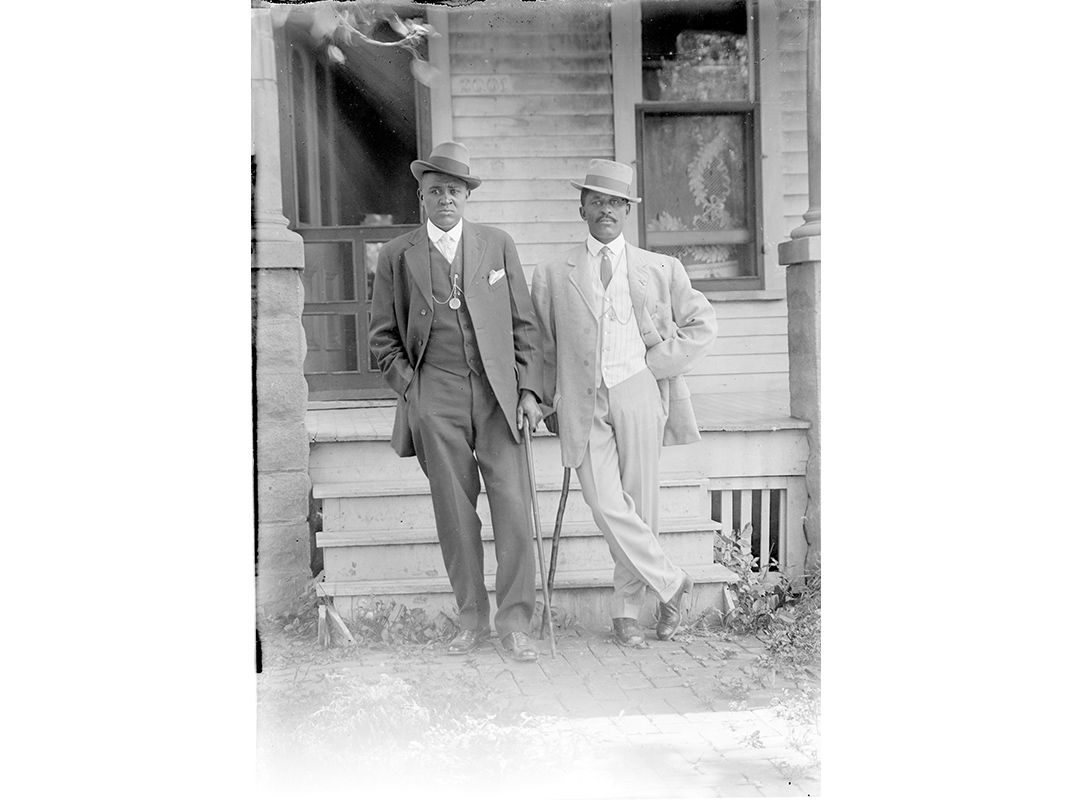

Farmer’s photograph keeps company with images dating from the 19th century through 2016. Images of subjects as well-known as Sojourner Truth, Malcom X and Michael Jordan accompany depictions of average people leading customary lives.

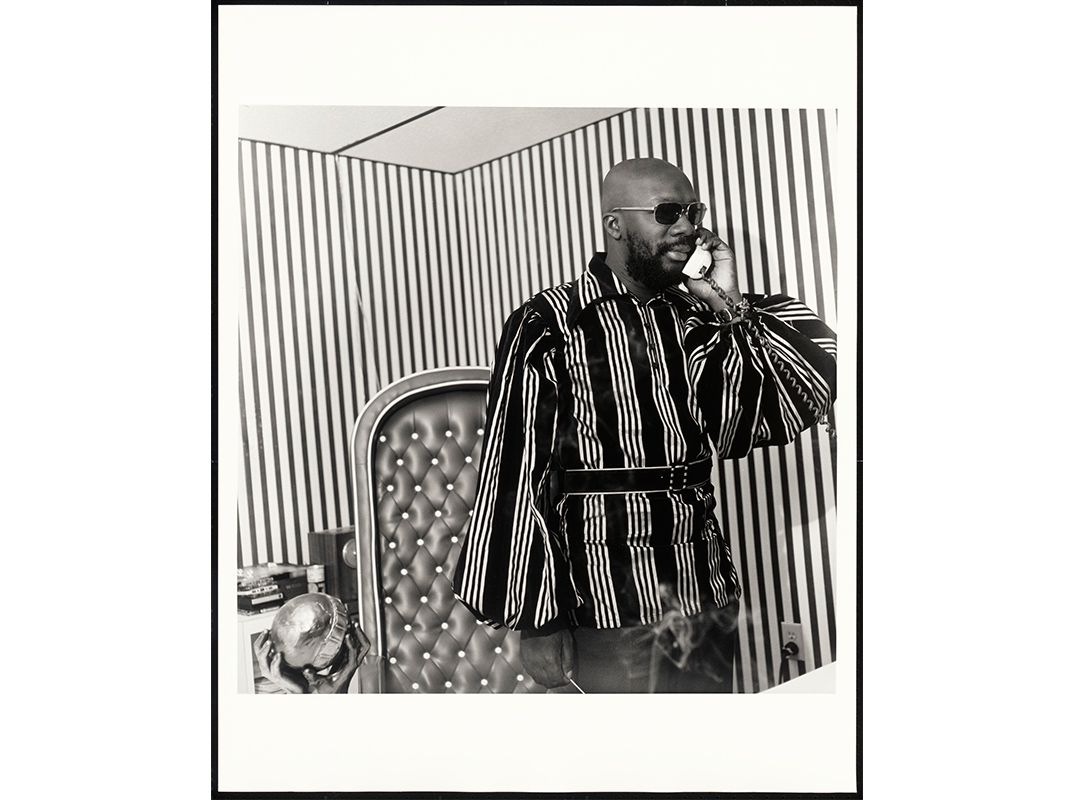

Contrasts mesmerize the viewer. At one end of the gallery, Queen Latifah’s mischievous likeness, from her days as a 1990s hip-hop star, smiles coyly from a frame. At the other end, the oldest picture in the exhibition depicts a group of enslaved women and their children posing placid on a plantation near Alexandria, Virginia.

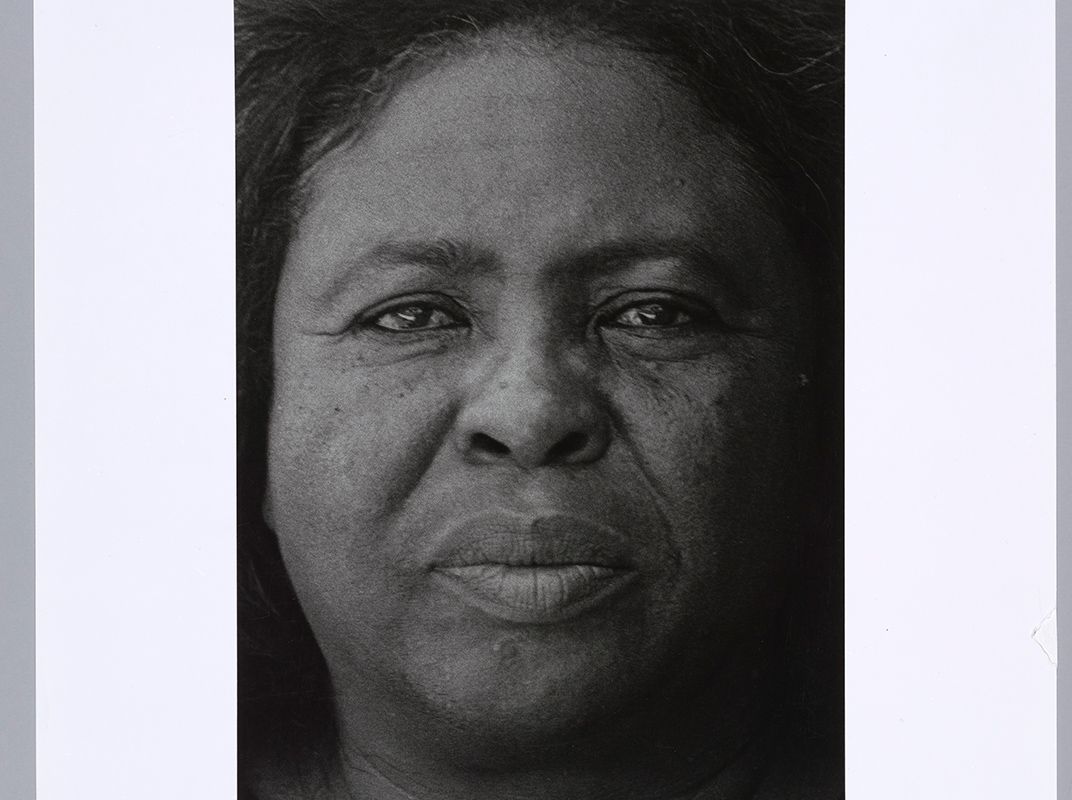

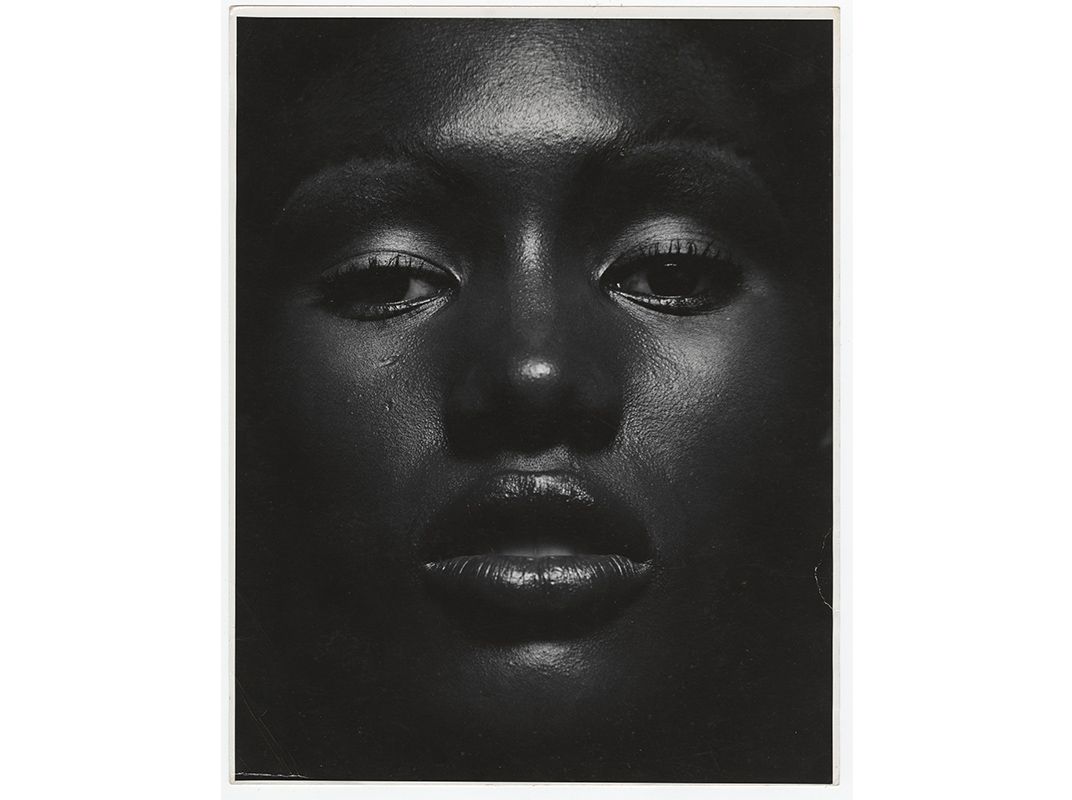

“We want to ask how photography might reflect the identities of individuals,” says Aaron Bryant, curator of photography and visual culture at the museum.

The photographers represent an extensive range of well-known and emerging photographers. Works by Pulitzer Prize-winning photographer John White and civil rights-era photojournalist Ernest Withers, buttress equally stunning works by lesser-known, emerging photographers, like Devin Allen and Zun Lee.

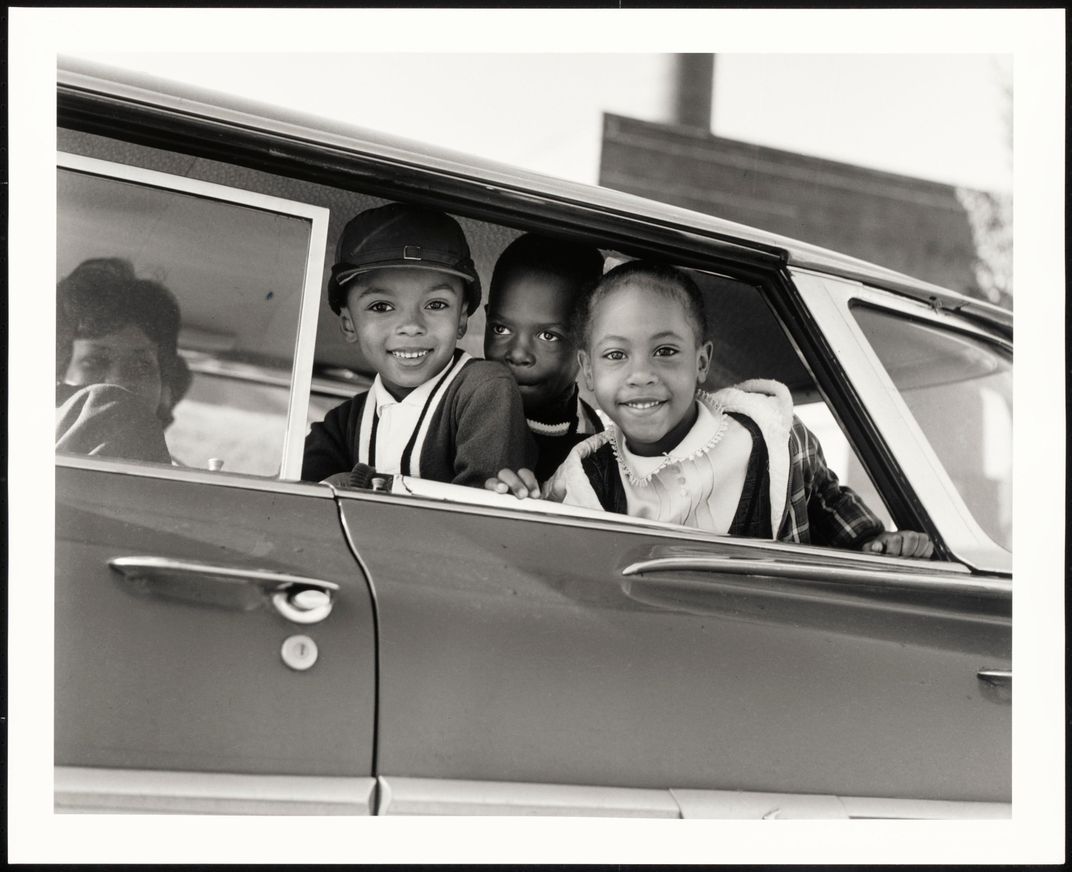

Allen was an amateur photographer snapping images of the 2015 protests in Ferguson, but his striking photo landed on the cover of TIME. Between 2011 and 2015, Lee, who is a physician based in Toronto, documented what he considered the overlooked aspects of black fatherhood. The photos follow fathers in New York and Atlanta.

“Knowing your history empowers you,” explains Gates-Moresi.

The images reveal the continuity of aspects of the African-American experience. A 1963 photograph by James H. Wallace, a photojournalist, depicting a group of young people lying on the ground in a civil rights protest sit-in, hangs just above a recent photograph by Sheila Pree Bright of a young woman lying in protest in Washington, D.C. Bright's interactive project #1960Now documents activism in the current age.

“Because photography has such a long trajectory in African-American life and American life, it’s the perfect template,” says Kinshasha Holman Conwill, the museum’s deputy director. “It’s one of the oldest forms, so we can tell a multitude of stories.”

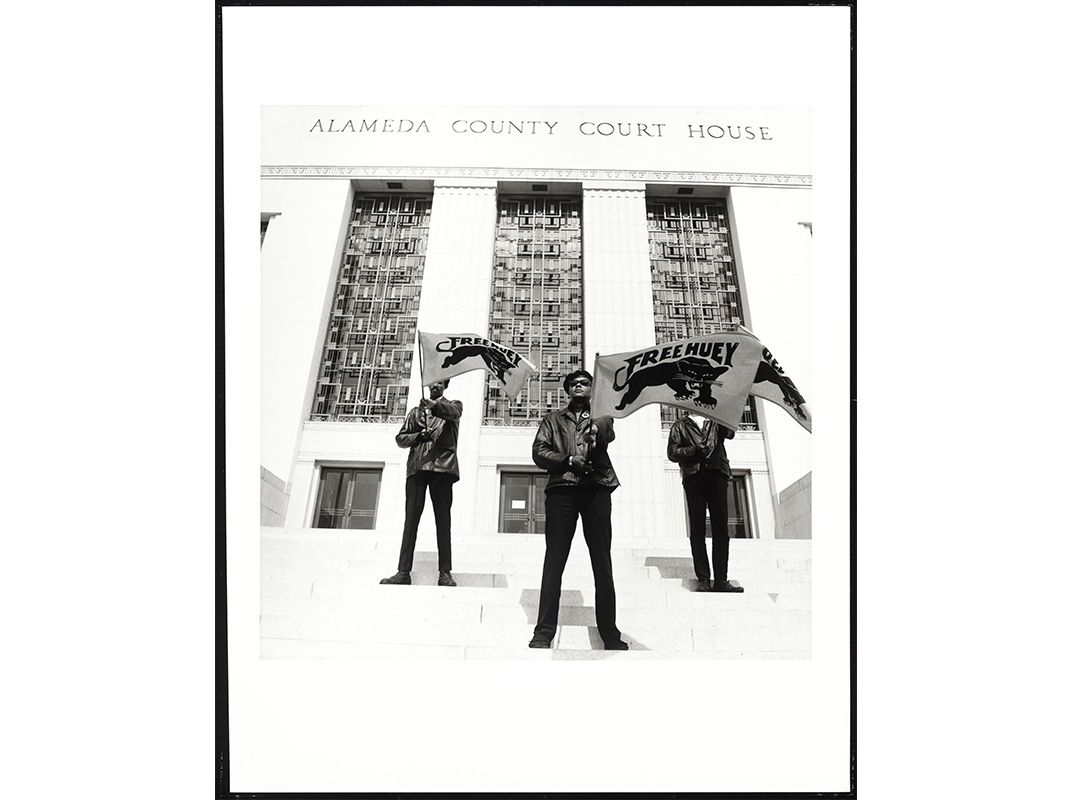

The curators supplemented the stories in the images by displaying accompanying artifacts near some of the photographs. A sign from the March on Washington that reads “We Demand an End to Police Brutality Now” complements a photograph of demonstrators carrying the same sign at the 1963 march.

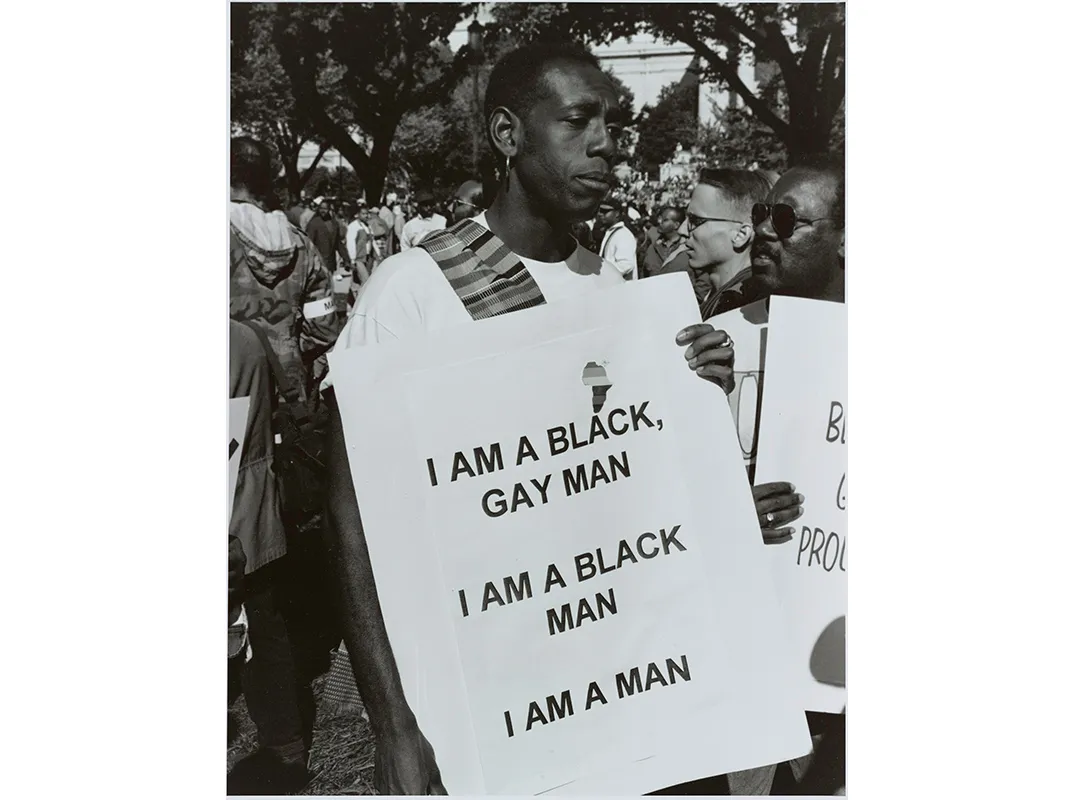

This photograph and artifact pairing is just one example of the many instances of activism illustrated in this exhibition. In addition to the photographs from the March on Washington, Black Panthers demonstrating in Oakland, California, and the Black Lives Matter protest in Baltimore, are images of Abolitionist Frederick Douglass, who was the most photographed American in the 19th century, appearing in a total of 160 photos. The show underscores the continuity of black activism across time and geography. African-American photographers have always employed “photography as a weapon,” notes Bryant.

The new temporary exhibition is not the museum’s first foray into curating photography. Of course, photographs play a major role in storytelling throughout the museum’s permanent exhibitions. And many photos from the museum’s collection appeared in a book series called Double Exposure, which was co-edited by Moresi and her colleague Laura Coyle. The books highlight several corners of the African-American experience from women to children to civil rights activism. The most recent highlights African-Americans in the military throughout American history.

“Behind every photograph, is a story about an individual and that individual’s story can reflect the culture or community,” says Bryant.

"More Than a Picture: Selections form the Photography Collection" is on view at the National Museum of African American History and Culture Museum in Washington, D.C., through May 5, 2017.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/DSC_0154.JPG.jpeg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/83/3d/833d87ad-b2c2-4061-b326-0eb533df23f6/2016_116_5_001-wr.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/76/31/7631b403-5e95-4d32-8d75-5b9979576295/2015_63_1_001.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/22/d7/22d7399a-3cb9-442e-82bb-4fa697defdf3/2013_245_001-wr.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/6c/99/6c991f07-e4e3-492e-be07-bd6f8b71892d/2013_207_1_001-wr.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/DSC_0154.JPG.jpeg)