Is Bob Dylan a Poet?

As the enigmatic singer, songwriter and troubadour takes the Nobel Prize in literature, one scholar ponders what his work is all about

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/07/cb/07cb2e8c-fbd0-400c-b1f4-4154f1f14b9a/npg9675web.jpg)

The 20th century was about the breaking of forms, transgressing the norms, and creating the new out of the multiplicities of influences in which we live. Early in the century, the poet Ezra Pound charged artists to “make it new,” creating art that responded to the time while also being mindful of the traditions from which it came. The Nobel Prize committee breaks with precedent—and recognizes those who make it new—by awarding the 2016 Nobel Prize in Literature to Bob Dylan.

The prize will surprise—and perhaps anger—some. In the 1960s and 1970s, there was no easier routine for a mainstream comedian to parody Dylan but to mumble obscurely while wheezing into a harmonica. Contemporary critics, who draw a hard line between high culture and popular art, lauding the former while disparaging the latter, will doubtless clutch their pearls in dismay.

But the award will delight many. Dylan’s career has been a constant series of surprises, reversals and new directions, from his roots as a New York “folkie,” channeling Woody Guthrie and the voice of America’s dispossessed to his later life fascination with the Old Testament and the Gospels.

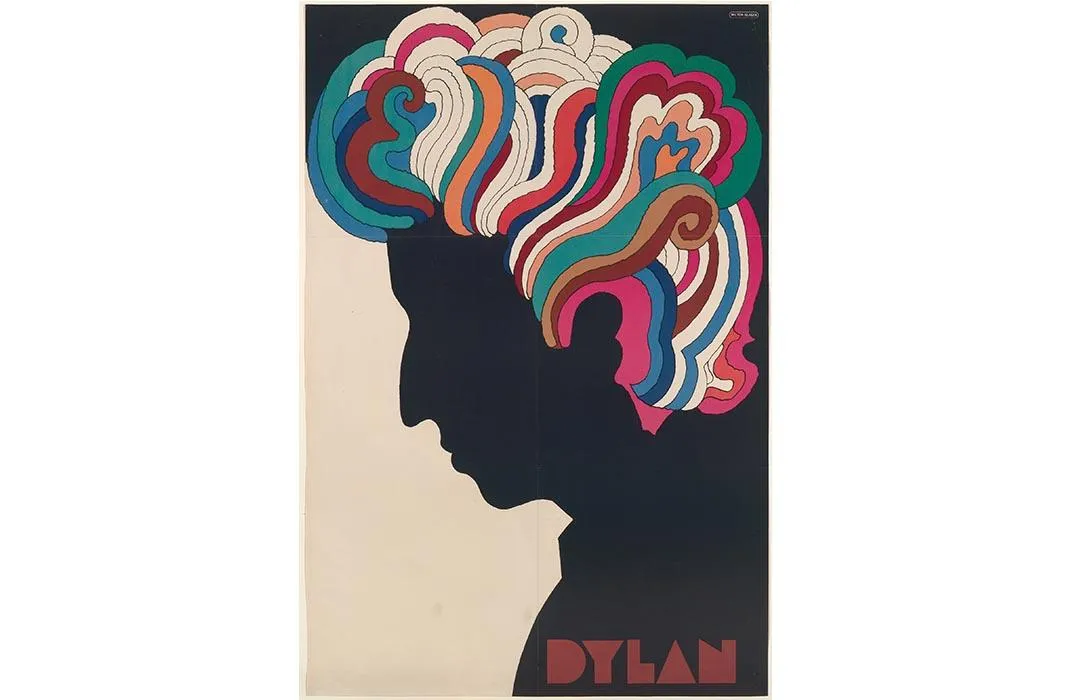

Most famously, in 1965 he turned everything upside down marrying his deeply rooted poetic lyrics to the sonic power of the electric guitar. The Prize Committee cited Dylan “for having created new poetic expressions within the great American song tradition.” That song tradition itself originated deep in the past with the medieval troubadours who fused word and music in their encounter with their life and times—so honoring Dylan, America’s troubadour—takes us full circle to poetry’s origins.

As a young man and aspiring artist, Hibbing, Minnesota’s Robert Zimmerman came out of the Iron Range—prime Guthrie territory—and took his stage name from the Welsh romantic poet Dylan Thomas. It was a persona that served him well even if Dylan was never as romantic in the sentimental sense of the word. Instead he was the singular individual, going his own way according to his own dictates and desires.

When he went electric he was accused of betrayal and treason by the outraged folk “community” he left behind. That world was too confining to his ambition and reach. In a succession of great albums, Dylan redefined the role of the singer/songwriter/performer in a way that was wholly original, not least because he lacked obvious musical gifts.

The comics weren’t altogether wrong.

Dylan proved that you could be a great singer without being able to sing—and he was never more than a rudimentary guitar player. But what he recognized was the marriage of words and music could propel a song based on ideas as much as rhythms. His music responded to the Civil Rights and Vietnam War protests of the late 1960s and; it was always civically and cultural engaged music. His raw voice chanted the lyrics in a way that made them all the more immediately powerful.

Do Dylan’s lyrics stand alone as poetry? Certainly they do in terms of the tradition of free verse in the 20th-century, a criterion that will not satisfy many.

And interestingly, because he turned words into music, many of his lyrics are more traditional in the way that they rhyme and scan than critics might admit.

Dylan cannot be seen as a traditional poet (like Frost, say) because surrealism always appealed to him in creating imagery that collided and turned one thing into something else. The great bitter lines of a romance gone bad in “Like a Rolling Stone” suddenly shift into something else entirely “You used to ride on the chrome horse with your diplomat/Who carried on his shoulder a Siamese cat” before returning to the present “Ain’t it hard when you discover that/He really wasn’t where it’s at. . .”

Granted the music carries the words, and like a lot of pop music sometimes the words can be conventional but where the hell did that image come from? And why does it work so well in the singer’s encounter with his spoiled and willful partner? These kinds of moments recur continually in Dylan’s songbook even when he is simply working in a familiar genre like country music or just rocking out with his greatest backup group, The Band.

“So,” Bob, quoting back at you the refrain from “Like a Rolling Stone,” how does it feel? Impressed by another honorific, a recognition of your singular role in the making and breaking of forms. Maybe, maybe not.

When asked once what his songs were about, Dylan responded, “About five and a half minutes.” Or as the song says, “Don’t think twice it’s alright.”

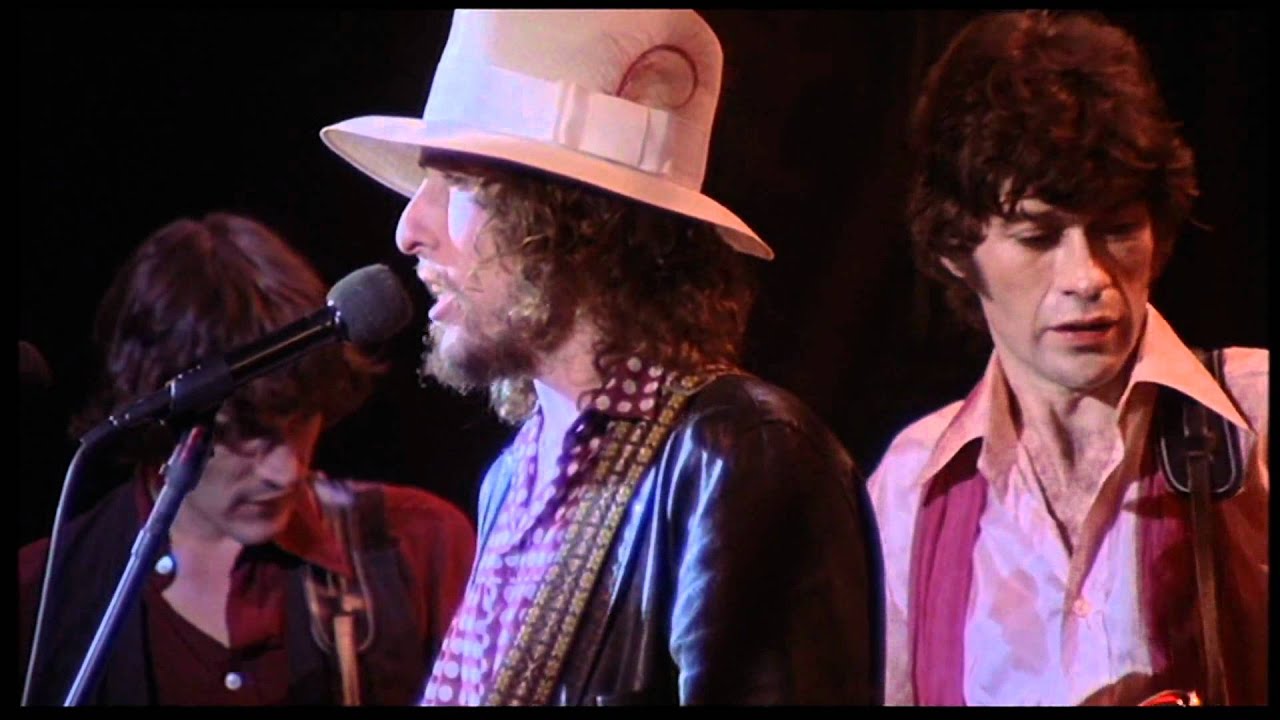

There is a great moment at the end of Martin Scorsese’ film The Last Waltz (his documentary about The Band's last concert) when Dylan comes out to close the show, wearing a very strange pink hat. He is received with rapturous, idolatrous applause, and looks full-faced into the camera and shrugs his shoulders in a gesture that says it’s all a bit much. And he and The Band then play the elegiac “Forever Young” (“May God bless and keep you always.”).

A nice way to end a show about ending, right? Except they don’t.

Finishing, they slam into “Baby Let Me Follow Down,” a Dylan song about the endless highway of sex, love, life and creativity: “I 'll do anything in this god almighty world/ If you’ll just let me follow you down.”

The Band is sadly gone now, most of its members dead; Dylan is still following himself.

The National Portrait Gallery will display its iconic 1962 image of Bob Dylan by photographer John Cohen beginning Monday, October 17, 2016.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/David_Ward_NPG1605.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/David_Ward_NPG1605.jpg)