Catch the Spiffy New Look for the Hall that Houses The Spirit of St. Louis, Bell X-1 and Other Famous Flyers

Just in time for its 40th birthday, the museum revamps its main exhibition hall and Star Trek “Enterprise” debuts

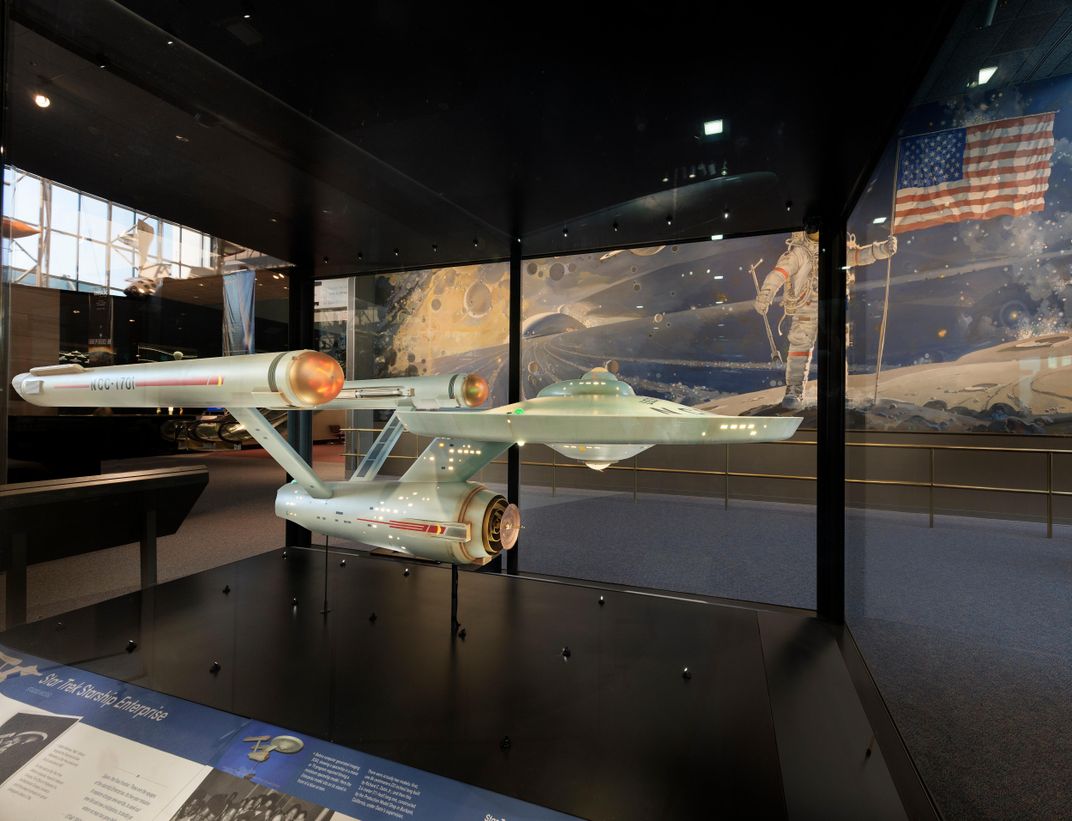

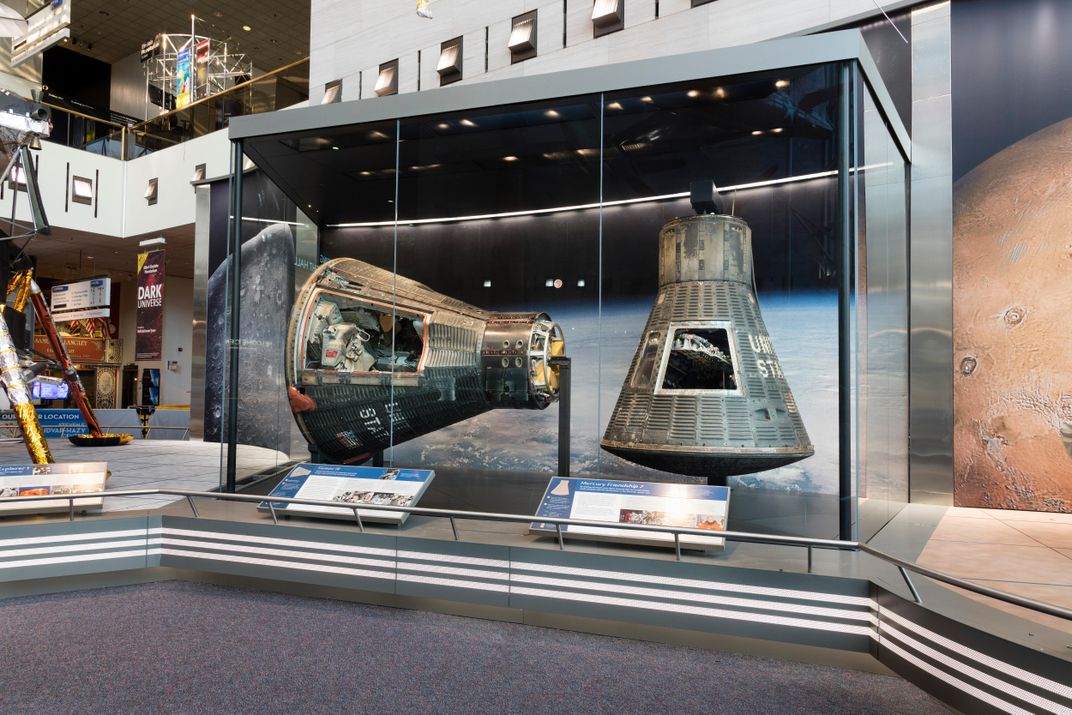

Ever since the National Air and Space Museum first opened on July 1, 1976, it has been one of Washington, D.C.'s most popular attractions. Just in time for the museum's 40th birthday, the main exhibition hall has reopened after a lengthy rejuvenation. Some old favorites remain while others have been added, like a lunar landing module built for the Apollo program. The original model of the Starship Enterprise greets "Star Trek" fans near an entrance and SpaceShipOne soars over a lofty corner. The result is an awe-inspiring exhibition space.

In gratitude for a $30 million gift from Boeing, the space has been named the "Boeing Milestones of Flight Hall."

The process of preparing the new exhibits became an opportunity not only to find new ways of presenting information to the public but also a chance for the staff to lower some old aircraft from suspension in mid-air and give them some over-due attention.

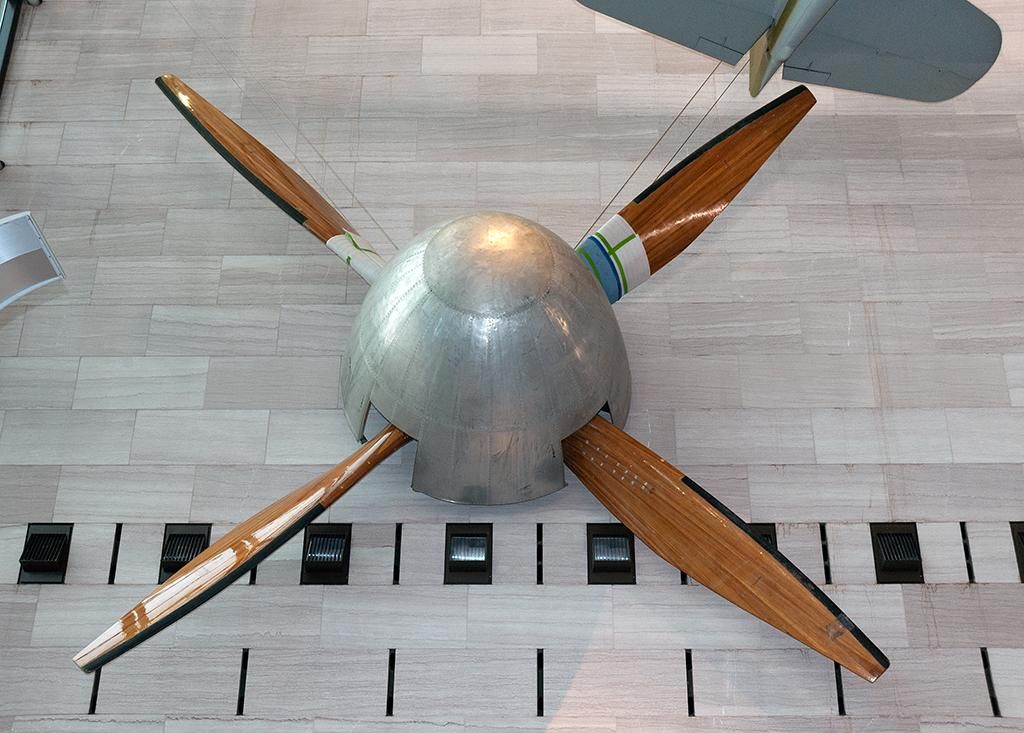

“We do our best these days not to restore,” says Bob van der Linden, a co-curator of the "Milestones of Flight" hall. He gestured up towards the Spirit of St. Louis, which Charles Lindbergh piloted in his famous 1927 trans-Atlantic flight. “It may seem like there's a difference without distinction but truly what we're trying to do is conserve it. We try to keep it as original as humanly possible for as long as humanly possible.”

Every scrap of aging fabric, including the patches hastily put on by an embarrassed French air force after an unruly crowd in Paris tore off souvenirs, has been maintained even as it dries and will eventually crumble.

“What we did do was clean it, says van der Linden. “Over the decades it got darker and darker and darker and we realized that most of this was dirt. . . it took them months to do it, literally with cotton swabs and a special water mixture. . . It looks so much nicer. It looked great before, but this is so much closer to what it looked like in the 1920's.”

A few surprises greeted the restoration team as they worked on some of the aircraft. One came from the famous Bell X-1 rocket plane, piloted in 1947 by Chuck Yeager when he became the first human to break the sound barrier.

“When we brought the X-1 down and cleaned it up quite a bit we discovered that the landing gear had been removed,” van der Linden says. “We didn't know that at the time.”

Another surprise was discovered in The Spirit of St. Louis.

“Underneath the front part of the engine, under the main fuel tank, they found a pair of pliers. We thought, huh, maybe we dropped them. We looked at the pliers and no, they were from 1927. . . We noticed that the paint that was on the grip matched perfectly the paint that the fuel tanks are covered with. . . . It was probably part of a tool kit [Lindbergh] had on the airplane.”

The somewhat cluttered center of the hall has been opened up to allow people to flow through the space more easily. Labels for items have been updated and rewritten to provide more in-depth information about the context of each object.

“Being the first is all well and good but there's so much more to it,” says van der Linden of the stories waiting to be told about the artifacts. “Yes, it's about science and technology but it's also about power and politics. It's about economics. It's about the people who built it. The tricky part is to present this to our visitors in such a way that they pick it up and understand it but they don't feel like I'm preaching to them. . . they're here to learn but they don't want to feel like they're in school.”

The objects in the collection might be ready to go for another 40 years. Cleaned, dusted, but still with the grit and wear that are part of their histories. Sally Ride's helmet still has a classic 1980s plastic label-maker name tag attached. “The main thing is that everyone is obsessed with keeping [The Spirit of St. Louis] as original as possible,” says van der Linden. “There may be a time some time in the future when the fabric is so dry that we have to replace it. . . I won't be there to do that. Hopefully someone who comes to replace me a couple hundred years from now.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/JacksonLanders.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/JacksonLanders.jpg)