The Bold Accomplishments of Women of Color Need to Be a Bigger Part of Suffrage History

An upcoming Smithsonian exhibition, “Votes For Women,” delves into the complexities and biases of the nature of persistence

:focal(1172x1297:1173x1298)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/d3/9d/d39d47f1-514c-4f4e-96a0-99eba49bdbc0/npg_79_220-truth-r.jpg)

The history of women gaining the right to vote in the United States makes for riveting material notes Kim Sajet, the director of the Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery in the catalog for the museum’s upcoming exhibition, “Votes For Women: a Portrait of Persistence,” and curated by historian Kate Clarke Lemay. “It is not a feel-good story about hard-fought, victorious battles for female equality,” Sajet writes of the show, which delves into the “past with all its biases and complexities” and pays close attention to women of color working on all fronts in a movement that took place in churches and hospitals and in statehouses and on college campuses. With portraiture as its vehicle, the task to represent the story proved challenging in the search and gathering of the images—the Portrait Gallery collection itself is historically biased with just 18 percent of its images representing women.

In this conversation, Lemay and Martha S. Jones, Johns Hopkins University’s Society of Black Alumni presidential professor and author of All Bound Up Together, reflect on the diverse experiences of the “radical women” who built an enduring social movement.

Many Americans know the names Susan B. Anthony or Elizabeth Cady Stanton, but the fight for suffrage encompassed a much wider range of women than we might have studied in history class. What “hidden stories” about the movement does this exhibition uncover?

Lemay: Putting together this exhibition was revealing of how much American women have contributed to history but how little attention we have paid them.

For example, when you think of African-American women activists, many people know about Rosa Parks or Ida B. Wells. But I didn’t know about Sarah Remond, a free African-American who in 1853 was forcibly ejected from her seat at the opera in Boston. She was an abolitionist and was used to fighting for citizenship rights. When she was ejected, she sued and was awarded $500. I hadn’t heard this story before, but I was really moved by her courage and her activism, which didn’t stop—it just kept growing.

The exhibition starts in 1832 with a section called “Radical Women,” which traces women’s early activism. You don’t think of women in these very buttoned-up, conservative dresses as “radical” but they were—they were completely breaking from convention.

Jones: Some of these stories have been hiding in plain sight. In the section on “Radical Women,” visitors are re-introduced to a figure like Sojourner Truth. She is someone whose life is often shrouded in myth, both in her own lifetime and in our own time. Here, we have the opportunity to situate her as a historical figure rather than a mythical figure and set her alongside peers like Lucy Stone, who we more ordinarily associate with the history of women’s suffrage.

The exhibition introduces us to more than 60 suffragists primarily through their portraits. How does this particular medium bring the suffrage movement to life?

Lemay: It’s interesting to see how formal, conventional portraits were used by these “radical women” to demonstrate their respectability. For example, in a Sojourner Truth portrait taken in 1870, she made sure to be portrayed as someone who wasn’t formerly enslaved. Being portrayed as such would have garnered her much more profit as the image would have been considered a more “collectible” item. Instead, she manifested dignity in the way that she dressed and posed . . . she insisted in portraying herself as a free woman.

We see a strong element of self-awareness in these portraits. Lucretia Coffin Mott, a great abolitionist, dressed in Quaker clothing that she often made herself. She was specific about where she sourced her clothing as well, conveying the message that it wasn’t made as a result of forced labor.

On the exhibition catalogue cover, we see Mary McLeod Bethune, beautifully dressed in satin and lace. The exhibition presents the use of photography as a great equalizer; it afforded portraiture to more than just the wealthy elite.

Jones: The other context for African-American portraits, outside the bounds of this exhibition, is the world of caricature and ridicule that African-American women were subjected to in their daily lives. We can view these portraits as “self-fashioning,” but it is a fashioning that is in dialog with, and opposition to, cruel, racist images that are being produced of these women at the same time.

I see these images as political acts, both for making claims about womanhood but also making claims for black womanhood. Sojourner Truth’s garb is an interesting mix of Quaker self-fashioning and finely crafted, elegant fabrics. The middle-class trappings behind her are worth noticing. This is a contrast to later images of someone like Ida B. Wells, who is much more mindful of crafting herself in the fashion of the day.

African-American suffragists were excluded from many leading suffrage organizations of the late 19th and early 20th centuries due to discrimination. How did they make their voices heard in the movement?

Jones: I’m not sure African-American women thought there was only one movement. They came out of many movements: the anti-slavery movement, their own church communities, self-created clubs.

African-American women were oftentimes at odds with their white counterparts in some of the mainstream organizations, so they continued to use their church communities as an organizing base, to develop ideas about women’s rights. The club movement, begun to help African-American women see one other as political beings, became another foundation.

By the end of the 19th century, many of these women joined the Republican Party. In cities like Chicago, African-American women embraced party politics and allied themselves with party operatives. They used their influence and ability to vote at the state level, even before 1920, to affect the question of women’s suffrage nationally.

Lemay: The idea that there were multiple movements is at the forefront of “Votes for Women.” Suffrage, writ large, involves women’s activism for issues including education and financial independence. For example, two African-American women in the exhibition, Anna Julia Cooper and Mary McLeod Bethune, made great strides advocating for college preparatory schools for black students. It’s remarkable to see what they and other African-American women accomplished despite society’s constraints on them.

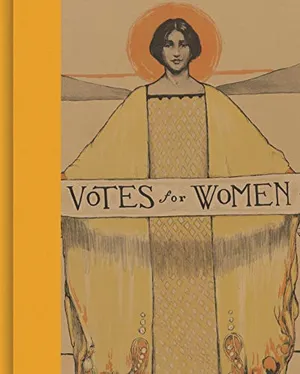

Votes for Women: A Portrait of Persistence

Bringing attention to under-recognized individuals and groups, the leading historians featured here look at how suffragists used portraiture to promote gender equality and other feminist ideals, and how photographic portraits in particular proved to be a crucial element of women's activism and recruitment.

The 19th Amendment, ratified in 1920, did not resolve the issue of suffrage for many women of color and immigrant women, who continued to battle for voting rights for decades. Might we consider the Voting Rights Act of 1965 part of the 19th Amendment’s legacy?

Jones: Yes and no. I can’t say that the intention of the 19th Amendment was to guarantee to African-American women the right to vote. I think the story of the 19th Amendment is a concession to the ongoing disenfranchisement of African-Americans.

We could draw a line from African-Americans who mobilized for ratification of the 19th Amendment to the Voting Rights Act of 1965, but we’d have to acknowledge that is a very lonely journey for black Americans.

Black Americans might have offered a view that the purpose of the 19th Amendment was not to secure for women the right to vote, but to secure the vote so that women could use it to continue the work of social justice.

Of course, there was much work to be done on the question of women and voting rights subsequent to the 19th Amendment. The Voting Rights Act of 1965 was the point at which black men and women were put much closer to equal footing when it comes to voting rights in this country.

Is there one particular suffragist in “Votes for Women” who stood out for her persistence, perhaps serving as a guidepost for activists today?

Lemay: All of the suffragists showed persistence, but two that come to mind are Zitkála-Šá and Susette LaFlesche Tibbles—both remarkable Native-American women leaders. Their activism for voting rights ultimately helped to achieve the Indian Citizenship Act of 1924, which granted citizenship to all Native-Americans born in the United States. But their legacy stretched well beyond 1924. In fact, some states excluded Native-Americans from voting rights through the early 1960s, and even today, North Dakota disenfranchises Native-Americans by insisting that they have a physical address rather than a P.O. box. More than a century ago, these two women started a movement that remains essential.

Jones: My favorite figure in the exhibition is Frances Ellen Watkins Harper. Here’s a woman born before the Civil War in a slave-holding state who was orphaned at a young age. She emerges onto the public stage as a poet. She goes on to be an Underground Railroad and anti-slavery activist. She is present at the Women’s Convention of 1866 and joins the movement for suffrage.

The arc of her life is remarkable, but, in her many embodiments, she tells us a story that women’s lives aren’t only one thing. And she tells us that the purpose of women’s rights is to raise up all of humanity, men and women. She persists in advocating for a set of values that reflect the principles of human rights today.

On March 29, the Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery opens its major exhibition on the history of women’s suffrage—“Votes for Women: A Portrait of Persistence,” curated by Kate Clarke Lemay. The exhibition details the more than 80-year struggle for suffrage through portraits of women who represent different races, ages, abilities and fields of endeavor.

A version of this article was published by the American Women’s History Initiative.

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/06/b3/06b3b8df-4d76-4e8b-80b1-6a454db2b60a/s_npg_79_26-zitkala-sa-r.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/33/43/3343ba48-bbfa-464b-86bb-53938d86271e/exhsu07.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/47/42/474249cc-ba1b-4a53-9005-4732853298f5/exhsu171.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/90/e8/90e85bbd-8c4c-488d-971b-1579b8cc5d44/exhsu118.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/d2/bd/d2bd5cc4-3b3e-4cd5-9a74-235acae3150d/lucretia_mott-r.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/61/8a/618ae694-ddc0-4b60-868c-bafc5b8bc155/npg_2009_36-wells-barnett-r.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/lemay-photo.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/jones.headshot.fall2018.1.jpg)