Bones Tell the Tale of a Maya Settlement

A new study tracks how the ancient civilization used animals for food, ritual purposes and even as curiosities

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/7c/b6/7cb69d50-d72b-434b-abc2-f1fb75cbb0bb/ashley_sharpe_jaguar_tooth_stri_credit_sean_mattson.jpg)

The jungle isn’t kind to bones. Acidic soils and warm temperatures often accelerate the rate of decay compared to cooler places, rapidly erasing the organic signatures of the organisms that lived in these lush places. But it’s difficult to entirely erase a shell or bone. Fragments can remain for thousands of years, and it’s a collection of these tiny pieces—more than 35,000 of them—that has offered a new perspective on what used to be a thriving Maya settlement.

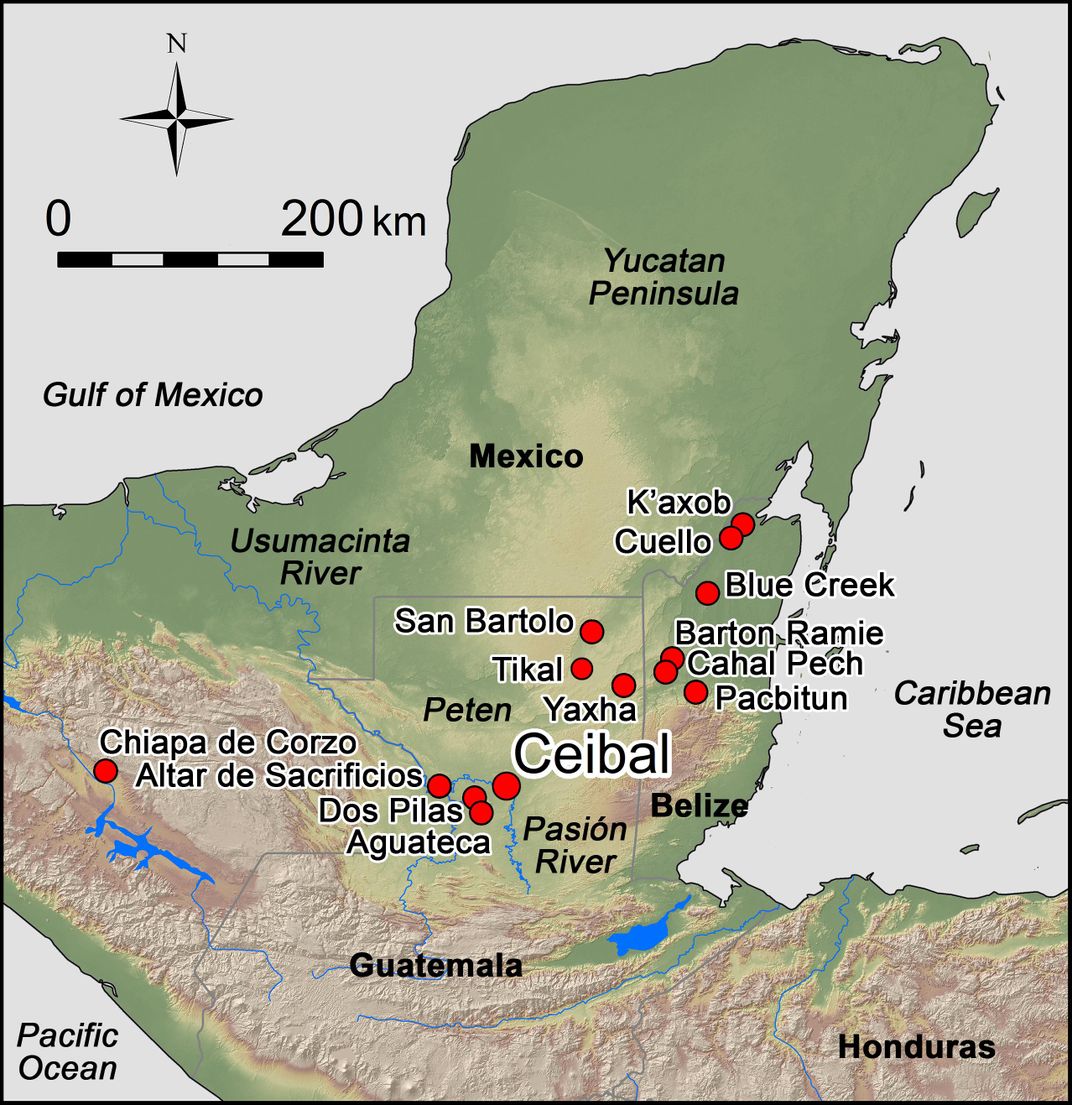

The area is called Ceibal. Located in present-day Guatemala along the banks of the Pasión River, this place was part of the Maya civilization for more than 2,000 years. And while there are certainly markers of human presence here, Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute archaeologist Ashley Sharpe and colleagues looked to a different set of evidence. When they dug into what remains of Ceibal, they were looking for traces of animals.

Zooarchaeology doesn’t get as much attention as archaeology itself does. Yet no understanding of humanity is complete without knowledge of the animals we lived with. “Zooarchaeology is a branch of archaeology which focuses on how humans and animals interacted in the past,” Sharpe says. By analyzing non-human remains from archaeological sites, researchers can piece together a sense of foodstuffs, if people kept domesticated animals, if certain creatures were important to human culture, and more.

“A lot of the objects we use every day, like clothes, jewelry, tools, musical instruments, and so on, were made out of animal parts in the past,” Sharpe notes, with animals inextricably tied to our culture.

From early excavations, it seemed that Ceibal held a rich zooarchaeological record. The researchers who began the Ceibal Archaeology Project noticed that animal bone and shell pieces were much more common at Ceibal than at other places. Sharpe joined the project in 2010 to dig into why.

“I helped excavate at the site for a few years after that,” Sharpe says, “and the experience working at the site and seeing where the animals were located in the grand scheme of this huge ancient city was really important for making interpretations.” This place was occupied for century after century, with layers of history stacked on top of each other.

To find the bony shards of antiquity, Sharpe and colleagues suspended soil samples from their excavations in water. Bone and shell pieces separated out and floated to the top. These fragments were then identified—sometimes only to a broader family, but often down to species. Each piece formed part of Ceibal’s record.

“The advances in analysis and interpretation have been made possible by exacting methods of faunal recovery,” says Florida State University archaeologist Mary Pohl, who was not involved with the study. Given the timespan the site records, sorting all the bones was a huge task for Sharpe and her colleagues. “The excavation at Ceibal stands out for the long depth of time covered, 2,200 years,” Pohl notes, “and that gives an excellent view of changes over time.”

The zooarchaeological collection, documented in a new PLOS ONE study by Sharpe and coauthors, outlines aspects of Maya life through their relationship with animals. Most of the animal remains were found in residential areas, Sharpe says, indicating that these were animals utilized by people and not just happenstance burials.

Prior to about 2,000 years ago, for example, the people of Ceibal relied on freshwater mussels and apple snails as a major food source. Shells of these animals have turned up in the thousands. One individual was even found with hundreds of apple snail shells—what may have been the core of a burial feast in their honor.

But something changed. In sediment layers after 2,000 years ago there are fewer mussels and snails. Fish, turtle and deer bones become much more common. People at Ceibal shifted their diet. The reason why isn’t yet clear. Perhaps local ecological changes made the invertebrate morsels less common. Maybe there was a cultural shift in the foods people wanted to eat.

In fact, what the people of Ceibal wanted to put on the dinner table might have shaped the nature of the area. In sediments dated after 200 A.D, for example, the researchers found an increase in bones from a river turtle called Dermatemy mawii. The turtles weren’t from here. It seems the Maya imported them from a place in modern day Mexico called the Isthmus of Tehuantepec.

“I think most people, even if they don’t consciously think about it, know that cows, horses, chickens and a lot of other animals originally came from Europe, Africa and Asia,” Sharpe says, “and those animals were moving around quite a lot for thousands of years.” But experts know relatively little about how animals were moved around the Americas, she notes, and these people moved animals and animal parts around for food, ritual purposes and even as curiosities just like other cultures.

Turkeys are another example. The birds were likely imported to Ceibal from areas in Mexico, and analyses of the chemistry inside the bones indicates that some of the birds were eating corn. Even though turkeys were originally raised for their feathers, in Ceibal they were likely finding their way to the table.

“The fauna coming from beyond Ceibal allow us to hypothesize about different kinds of human activities that would be invisible otherwise,” Pohl says. The story of the animals records the shifting culture.

The consistency of these patterns through time was striking, Sharpe says. The decline in shells tracks across the remains of the city, as well as the rise of turkeys hundreds of years later. “Certain marine species, usually shells for beads, only appear at certain times, almost like temporary fads,” she notes. The animals help set the tempo for how society itself evolved.

“In societies like the Maya, where we have very few written records,” Sharpe says, “any clues concerning events in history are incredibly valuable.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/RileyBlack.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/RileyBlack.png)