A Brief, 500-Year History of Guam

The Chamorro people of this Pacific island have long been buffeted by the crosswinds of foreign nations

:focal(-293x-557:-292x-556)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/ba/37/ba3718cc-3678-4482-9eb5-1c3122d0a29d/ap_070627012241.jpg)

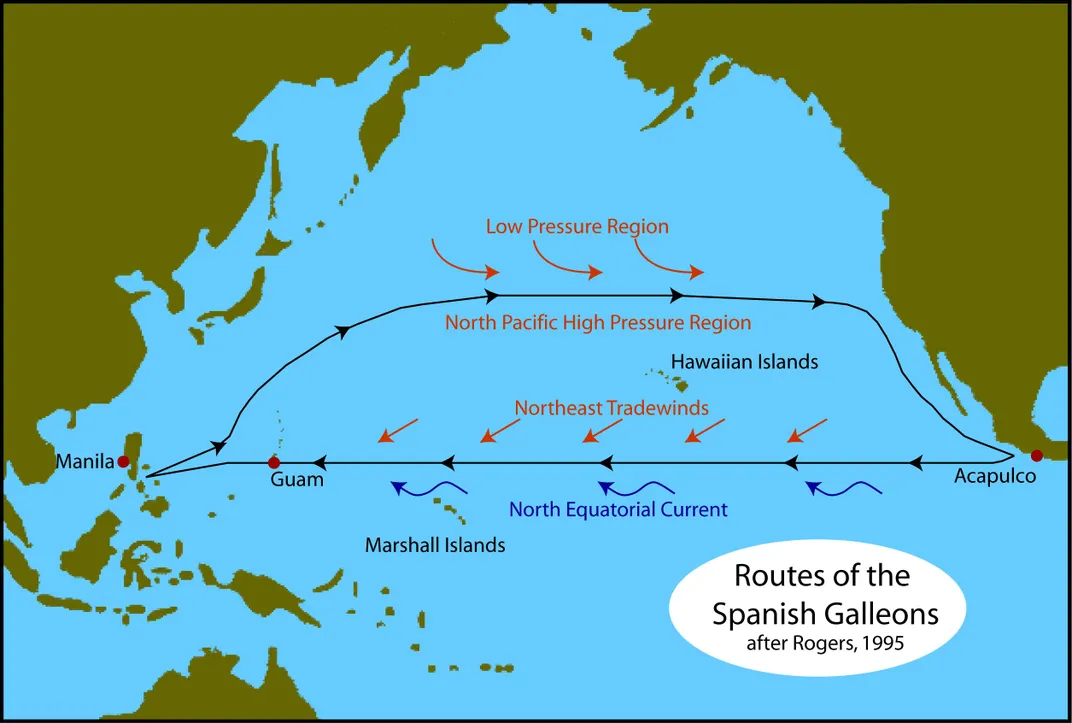

That Guam once again finds itself in the crosshairs of foreign adversaries is nothing new. It was 500 years ago, in 1521, when Ferdinand Magellan’s ships, weary and hungry, pulled up to this island, beginning 300 years of Spanish conquest. Nowadays most Americans, if they know of Guam at all, think of this and neighboring Saipan as sites of World War II battles. It was from neighboring Tinian that the Enola Gay took off to drop the bomb on Hiroshima. And as is always the case in these struggles between external powers, the presence of the Chamorro, the indigenous peoples of the islands, is lost.

Most Americans likely have some inkling that Guam exists and is somehow American. Few know how or why. While geographically, Guam is among the Mariana Islands, so named by Spanish missionaries in 1668, it is a separate U.S. territory from the Northern Mariana Islands, which is technically a commonwealth. Guam remains on the United Nations list of 17 non-self-governing territories—colonies, that, under the U.N. charter, should be de-colonized. It’s “American soil,” but the residents do not have full American citizenship, and cannot vote in presidential elections. They have a non-voting representative to Congress.

In 2002, I conducted community-based research in the southern village of Inarahan (Inalahan in Chamorro). The project, Pacific Worlds, is an indigenous-geography cultural documentation and education project, sponsored by Pacific Resources for Education and Learning (PREL). Later I did a similar project in Tanapag village on nearby Saipan, part of the Northern Mariana Islands, and published a paper about the history of colonialism (American, in particular) in the region.

I do not speak for the Chamorro people, but as a scholar of colonialism and indigeneity, who was taught directly by the people who shared their lives with me. The full community study, with maps, photos and illustrations, can be found here, but given the current circumstances, a short history is merited.

People arriving from islands off Southeast Asia, most likely Taiwan, settled Guam and the Marianas more than 4,000 years ago. One could sail west-to-east from the Philippines to the Marianas just by following the sun. A clan-based society arose by 800 A.D. that included villages characterized by impressive latte houses, one-story houses set atop rows of two-piece stone columns; these were still in use as late as 1668. Archaeological evidence indicates rice cultivation and pottery making prior to European arrival in the 16th century. By then, the Chamorros had developed a complex, class-based matrilineal society based on fishing and agriculture, supplemented by occasional trade visits from Caroline Islanders.

The Mariana Islands proved not terribly useful to the Spanish. “Magellan’s view of the world as a Portuguese Catholic in the early 1500s did not help the encounter,” explains Anne Perez Hattori, a Chamorro historian at the University of Guam. “On seeing the Chamorros, he did not view them as his equals…. He definitely viewed them as pagans, as savages…. [T]he Chamorros took things. And then because of that, Magellan calls the islands the ‘Islands of Thieves.’"

Magellan's characterization of the Chamorros as "thieves," discouraged further European intrusion; and while some ships still visited, the Chamorros lived in relative isolation for the next century or so. The nearby Philippines, where traders found an entryway to the Chinese market, attracted most of the seafarers from abroad.

That all changed when an aggressive Jesuit missionary, Father San Vitores, arrived in the Marianas in 1668. Relations were tense with occasional violence. In 1672, San Vitores secretly baptized the infant daughter of a local chief, Matå‘pang, against the chief’s wishes, a last straw that ended with San Vitories' death.

His death was the turning point that transformed this hitherto-ignored Spanish outpost into a subjugated Spanish colony.

“After San Vitores dies, the military took over the mission, so it became really a war of subjugation,” Hattori says. Twenty-six years of Spanish-Chamorro wars ensued that, along with introduced diseases, decimated the population. By 1700, just 5,000 Chamorros—some 10 percent of their former number—remained.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/1f/20/1f205fd4-d979-4fcc-8a39-26dcd6727f4d/6908669081_43d5a4500b_o.jpg)

The Spanish then began transporting Chamorros from the northern islands to Guam, where they could control them—a process that took nearly a century, as the fast native canoes could outrun the larger and slower Spanish ships and elude capture. Canoe culture was then banned to keep them from escaping.

Once on Guam, the Chamorros were resettled into newly created villages, each under the watchful eye of a Spanish priest. And so began the assimilation of the Chamorros. They lost their millennia-old connections to the land, their traditions and their stories. Today, the Chamorro language retains its traditional grammar, but 55 percent of the vocabulary borrows from Spanish.

Nonetheless, indigenous culture continued in other ways—in values, in traditions surrounding weddings and funerals, in housing styles, and many other forms not obvious to the outsider. Small-island living requires a system of codes and practices, evolved over millennia, which no outside culture can replace, even today.

The Spanish maintained a lazy rule over the islands for the next century and a half. The northern islands were off limits, until typhoon-devastated Caroline Islanders arrived from the south—as was their traditional practice—looking for temporary shelter around 1815. The Spanish governor settled them on Saipan, where they still live alongside of—if not intermarried with—Chamorros who were allowed to return there in the mid-19th century.

The Spanish empire was approaching its twilight years by the time the United States acquired California from Mexico in 1848, an era when the ideology of “manifest destiny” justified aggressive American expansion.

By 1898, with the Spanish-American War, the nation’s ambitions expanded beyond the U.S. continent, and extended American “Indian-hating” to the far western Pacific.

The Spanish troops and officials stationed in Guam were at first glad to have visitors when the USS Charleston arrived. They didn’t know that war had been declared between the two nations, and mistook their cannon fire for a salute. A peaceful transfer of power ensued.

The 1898 Treaty of Paris between Spain and the U.S. would later formalize the handover of Guam. The reason why Guam remains a U.S. territory, while the rest of Micronesia is not, can be traced to an ironic accident of history and geography. The American negotiators neglected to inquire about the Spanish claims to the rest of the Marianas and much more of Micronesia, and Spain quickly sold these other islands to Germany. Thus began a rift between the Chamorros of Guam and those of the Northern Mariana Islands.

Guam has persisted under American rule to the present day, while the northern islands experienced first almost two decades of benign German rule, then nearly three decades under the thumb of the Japanese empire, which took all of Germany’s Pacific territories at the outset of World War I.

Right after the U.S takeover, the leading families of Guam met and established a legislature in anticipation of a democratic, representative government. To their surprise, the island was instead placed under the jurisdiction of the Secretary of the Navy, and was ruled by a series of military governors who, though generally benign, wielded absolute authority. The Navy maintained the island—both physically and discursively—as an essential American forward base, and under their administrations, Guam was run like a well-ordered battleship under what was essentially martial law.

In a series of Supreme Court rulings known as the Insular Cases of 1901, it was decided that new territories might never be incorporated into the union and were to receive only unspecified ‘‘fundamental’’ Constitutional protections. They were to be governed without the consent of the governed in a system that lacked the checks and balances that underlie the principle of limited government.

As one legal scholar noted in 1903, the new insular possessions became “real dependencies—territories inhabited by a settled population differing from us in race and civilization to such an extent that assimilation seems impossible.” With these newly acquired lands, the U.S. became an empire in the manner of Britain, France and Germany. The contradiction of a “free,” “democratic” country holding colonies unfolded powerfully on Guam over the ensuing century.

The Chamorros persisted in their pursuit of democracy, sometimes with moderate support from the naval governors, sometimes not, but always without success.

As late as 1936, two Guam delegates, Baltazar J. Bordallo and Francisco B. Leon Guerrero, went to Washington to petition in person for Chamorro citizenship.

They were positively received by President Franklin Roosevelt and by members of Congress. But the Navy convinced the federal government to reject the petition. As Penelope Bordallo-Hofschneider writes in her book A Campaign for Political Rights on the Island of Guam, 1899-1950, the Navy cited, among other things, “the racial problems of that locality” and asserted that “these people have not yet reached a state of development commensurate with the personal independence, obligations, and responsibilities of United States citizenship.”

While the bombing of Pearl Harbor still lives on in infamy in American memory, the bombing of Guam—four hours later—is virtually forgotten. In a brief but locally well-remembered air and sea attack, Japanese troops seized control of the small American colony and began an occupation that lasted three years. More than 13,000 American subjects suffered injury, forced labor, forced march or internment. A local priest, Father Jesus Baza Dueñas, was tortured and assassinated. At least 1,123 died. To America, they are forgotten.

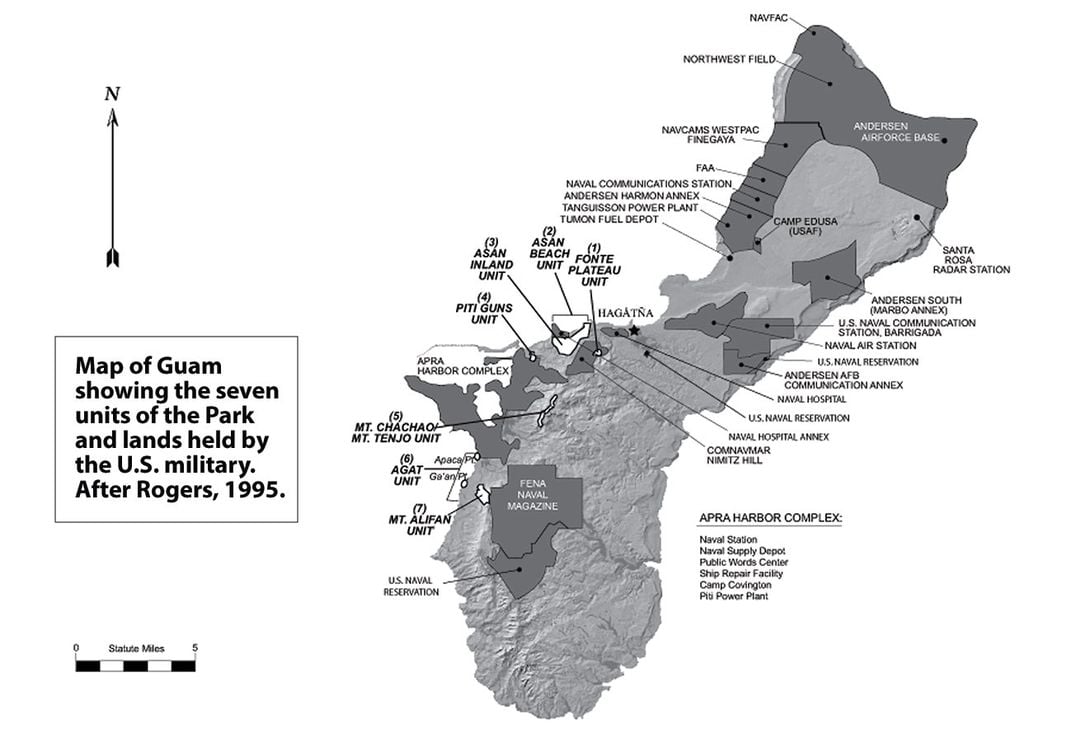

The battle to re-conquer Guam from the Japanese, however, does stand out, at least for war buffs. The National Park Service commemorated it with a park spanning seven different locations. It virtually dominates the landscape. It was not until 1993, with the 50th anniversary of the liberation approaching, that Congress was moved by Guam’s congressional representative, Robert Underwood, to overtly recognize the suffering of the Chamorros. Public Law 103-197 authorized construction of a monument to commemorate, by individual names, those people of Guam who suffered during the occupation.

In his book Cultures of Commemoration: The Politics of War, Memory and History in the Mariana Islands, Chamorro scholar Keith Camacho remarks that in military narratives of World War II’s Pacific theater, Pacific Islanders play no central role. Instead, military historians tend to envision the Pacific Islands as “a tabula rasa on which to inscribe their histories of heroism and victimization,” forming “a body of discourse in which only Japanese and Americans constitute the agents of change and continuity in the region, erasing the agency and voice of indigenous peoples.”

Whatever happens with North Korea, which has threatened to attack Guam with a nuclear weapon, let us not forget that Guam and its fellow Mariana Islands are a locus of indigenous peoples, culture, history and traditional civilization. This is not just a U.S. military base, but a place with a long history and deep cultural roots, whose “American” people have striven for democracy for over a century, and still don’t have it.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Doug-BPBM-2011.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/e1/72/e1727c33-2de3-4ef6-b655-6e14a6f43fef/figure_1.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/ac/89/ac89447e-ea86-4f3b-b9ef-07d550b3999e/table1web.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/14/a7/14a763ad-6e39-44d3-a249-d1482892fee0/table2web.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/26/e7/26e7b6f6-f52e-4360-ba60-25ffe527c60e/two_peoples.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Doug-BPBM-2011.jpg)