The Broadway Revival of “Fiddler” Offers a Profound Reaction to Today’s Refugee Crisis

Popular musicals on Broadway are regarded as escapist, but the worldwide issue of migration and displacement is inescapable

:focal(510x143:511x144)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/eb/4b/eb4b2eb5-26e1-4dd9-a4cb-1b838164d584/newfiddlerweb.jpg)

The play and film Fiddler on the Roof is tradition. Indeed when Tevye, the Jewish dairyman and protagonist of this much-beloved musical begins his eight-minute jubilant tribute to tradition in song and dance, there are few among us who don’t unconsciously mouth the words alongside him: “Without our traditions, our lives would be as shaky as a fiddler on the roof.”

So it is most noteworthy when the new hit revival of Fiddler on the Roof—which opened December 20, 2015, at New York City’s Broadway Theatre—deliberately breaks with tradition in its opening and closing scenes.

Instead of portraying Tevye wearing his familiar turn-of-the-20th-century cap, work clothes and prayer shawl in his Russian village, the new version introduces him bareheaded, wearing a modern red parka, standing in front of a ghostly, weathered sign reading Anatevka. As Tevye begins reciting the familiar words about keeping one’s balance with tradition, the villagers gradually gather on stage.

Similarly, when Anatevka’s Jews are forced to leave their homes by order of Russian authorities, ca. 1906, Tevye reappears once again wearing his red parka and silently joins the group of migrants being displaced.

“You see him enter the line of refugees, making sure we place ourselves in the line of refugees, as it reflects our past and affects our present,” Bartlett Sher, the show’s director, told the New York Times. “I’m not trying to make a statement about it, but art can help us imagine it, and I would love it if families left the theater debating it.”

Popular musicals on Broadway are often regarded as escapist, but the worldwide issue of migration and displacement is inescapable. “Wars, conflict and persecution have forced more people than at any other time since records began to flee their homes and seek refuge and safety elsewhere,” according to a June 2015 report from the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees.

With worldwide displacement at the highest level ever recorded, the UNHCR reported “a staggering 59.5 million compared to 51.2 million a year earlier and 37.5 million a decade ago.” It was the highest increase in a single year and the report cautioned that the “situation was likely to worsen still further.”

Migration and displacement were central to Fiddler on the Roof’s story long before the musical made its Broadway debut on September 22, 1964, and then ran for 3,242 performances until July 2, 1972—a record that was not eclipsed until 1980, when Grease ended its run of 3,388 performances.

The stories of Tevye and Jewish life in the Pale of Settlement within the Russian Empire were created by humorist Shalom Rabinovitz (1859–1916), whose Yiddish pen name Sholem Aleichem literally translates as “Peace be unto you,” but which may also mean more colloquially “How do you do?”

Although successful as a writer, Rabinovitz continually had difficulty managing his earnings. When he went bankrupt in 1890, he and his family were forced to move from a fancy apartment in Kiev to more modest accommodations in Odessa. Following the 1905 pogroms—the same anti-Semitic activities that displaced the fictional Jews of Anatevka from their homes—Rabinovitz left the Russian Empire for Geneva, London, New York, and then back to Geneva. He knew firsthand the travails of migration and dislocation.

Rabinovitz’s personal travails shape his best-known book, Tevye the Dairyman, a collection of nine stories that were published over a period of 21 years: the first story, “Tevye Strikes It Rich,” appeared in 1895, though Rabinovitz wrote it in 1894, not imagining that it would be the first of a series; the final story, “Slippery,” was published in 1916.

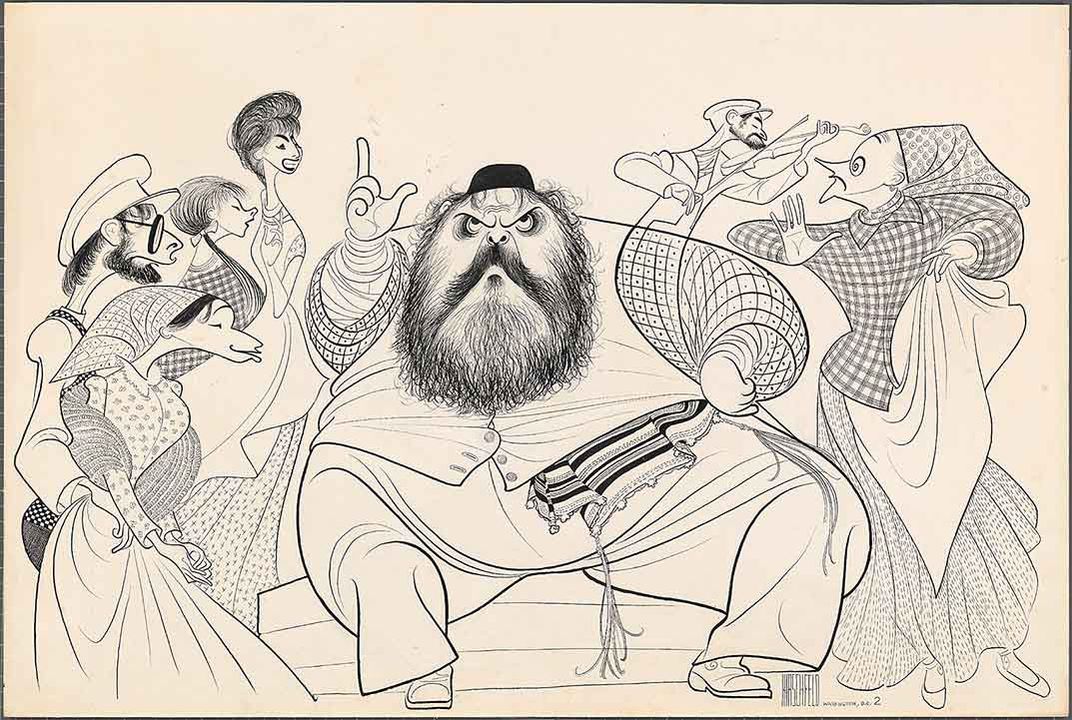

Numerous adaptations appeared, including several stage plays and a 1939 Yiddish-language film, Tevye, before the team of Jerry Bock (music), Sheldon Harnick (lyrics), Jerome Robbins (choreography and direction), and Joseph Stein (book) adapted several of the Tevye stories to create Fiddler on the Roof for Broadway, taking their title not from Rabinovitz, but from one of Marc Chagall’s paintings.

Going back to the original stories reveals a Tevye who suffers much more than the joyful, singing character seen on Broadway in 1964 and also as played by the Israeli actor Topol in the 1971 film version.

The riches that Tevye strikes in the first of the published stories are lost completely in the second. The hopes that Tevye holds in finding rich husbands for five of his daughters are dashed again and again. Tsaytl marries a poor tailor; Hodel marries a poor revolutionary, who is exiled to Siberia; Chava marries a non-Jew, causing Tevye to disown her; Shprintze drowns herself when rejected by a wealthy man; and Beylke’s husband deserts her when his business bankrupts. Tevye’s wife Golde dies, and he laments, “I have become a wanderer, one day here, another there. . . . I have been on the move and know no place of rest.”

A Broadway musical like Fiddler on the Roof needed an ending not so bleak for Tevye, but still managed to convey some of the pain of forced migration and dislocation. In “Anatevka,” for instance, members of the chorus solemnly sing, “Soon I'll be a stranger in a strange new place, searching for an old familiar face.” The song concludes with one character lamenting, “Our forefathers have been forced out of many, many places at a moment’s notice”—to which another character adds in jest, “Maybe that’s why we always wear our hats.”

When Fiddler first appeared on stage in 1964, several critics noted how the musical was able to raise serious issues alongside both the jesting and the schmaltz. Howard Taubman’s review in the New York Times observed, “It touches honestly on the customs of the Jewish community in such a Russian village [at the turn of the century]. Indeed, it goes beyond local color and lays bare in quick, moving strokes the sorrow of a people subject to sudden tempests of vandalism and, in the end, to eviction and exile from a place that had been home.”

Fiddler on the Roof has been revived on Broadway four times previously—in 1976, 1981, 1990, and 2004—and it is relevant to note that when Broadway shows like Fiddler or Death of a Salesman (1949) or A Raisin in the Sun (1959) return to stage, we call them revivals.

On the other hand, when films like The Mechanic (1972), Arthur (1981), and Footloose (1984) all reemerged in 2011, we referred to the new versions as remakes. It’s an important difference.

A revival brings something back to life, but a remake suggests something much more mechanical, as if we’re simply giving an old film like Psycho (1960) a new look in color. The current revival of Fiddler not only brings the old show back to life; it also invests it with something more meaningful and enduring—and not at all shaky, like a fiddler on the roof.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/James_Deutsch.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/James_Deutsch.jpg)