Can the Civil War Still Inspire Today’s Poets?

As epic verse about the American past falls victim to modernism, a poet who is also a historian calls for a revival

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/93/35/9335c6d4-b403-4e2a-b948-e3845682a818/home-of-a-rebel-sharpshooterexhag84web.jpg)

Very few contemporary American poets write history poems. Poetry that addresses the past by using the examples of specific people or events was a major part of American literature throughout the 19th century.

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow made a staple of subjects like “Paul Revere’s Ride.” Herman Melville, who wanted to be known as a poet and not as a novelist, wrote several very fine poems about the Civil War, including one on “weird” John Brown.

In the 20th century, full-fledged history poems seem to have ended with Robert Lowell, who engaged the past of his Puritan forbears in his verse and whose “For the Union Dead” is perhaps the finest poem written about the Civil War.

Southern poets have always used their region’s history as a subject, seeking to make sense of the legacy of defeat in the Civil War, as well as the legacy of race (and racism) and slavery. But even this vein seems to have died out.

History poems likely disappeared with modernism, and now post-modernism: both of which stress the interiority of the writer and avoid specific, historically situated subjects.

So poets write about cultural conditions, even the condition of American democracy and society, but do so obliquely, without trying to describe or inhabit the predicament of an historical figure, or place themselves in the midst of events in past-time.

When curator Frank Goodyear and I asked 12 contemporary poets to write about the Civil War for our 2013 book, Lines in Long Array, the majority of the poets initially hesitated, concerned about how to approach the subject. They all turned out to be pleased with the result although they may not have made a habit out of it.

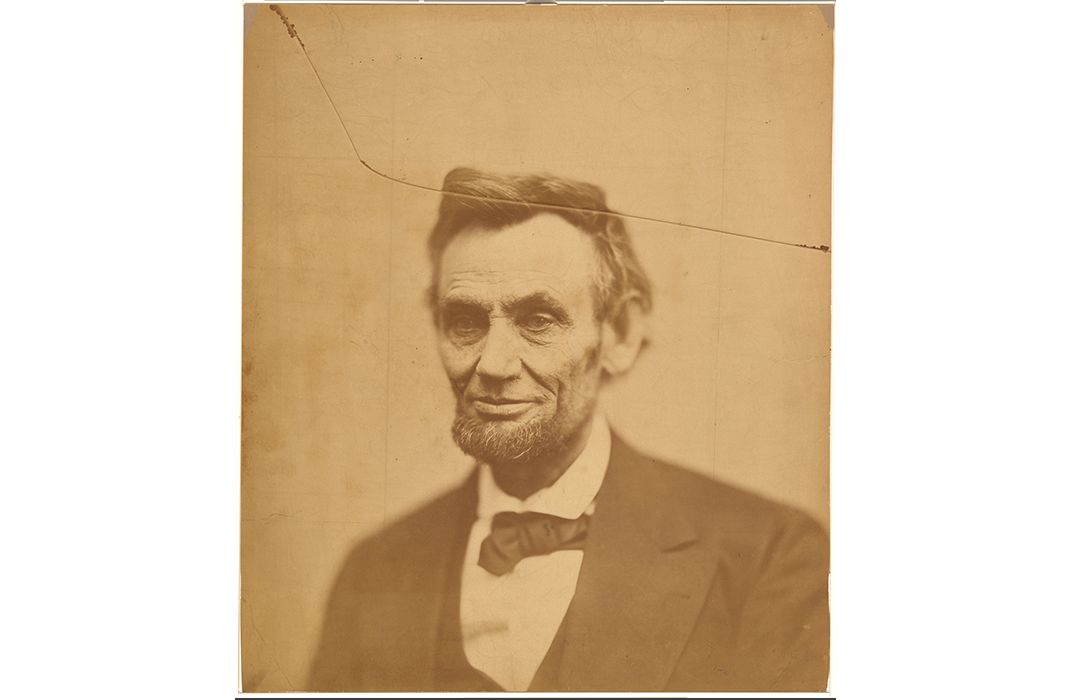

Steve Scafidi came recommended to us by poet Dave Smith for his poems on Lincoln, now collected in his 2014 To the Bramble and the Briar. His “Portrait of Abraham Lincoln with Clouds for a Ceiling” imagines the President just about to speak at Gettysburg: “He could feel his pinky toe/push through the hole in his sock, and a rash form/on his neck” and ends with “a testimony for this/new church//founded in Gettysburg, in hope. . .”

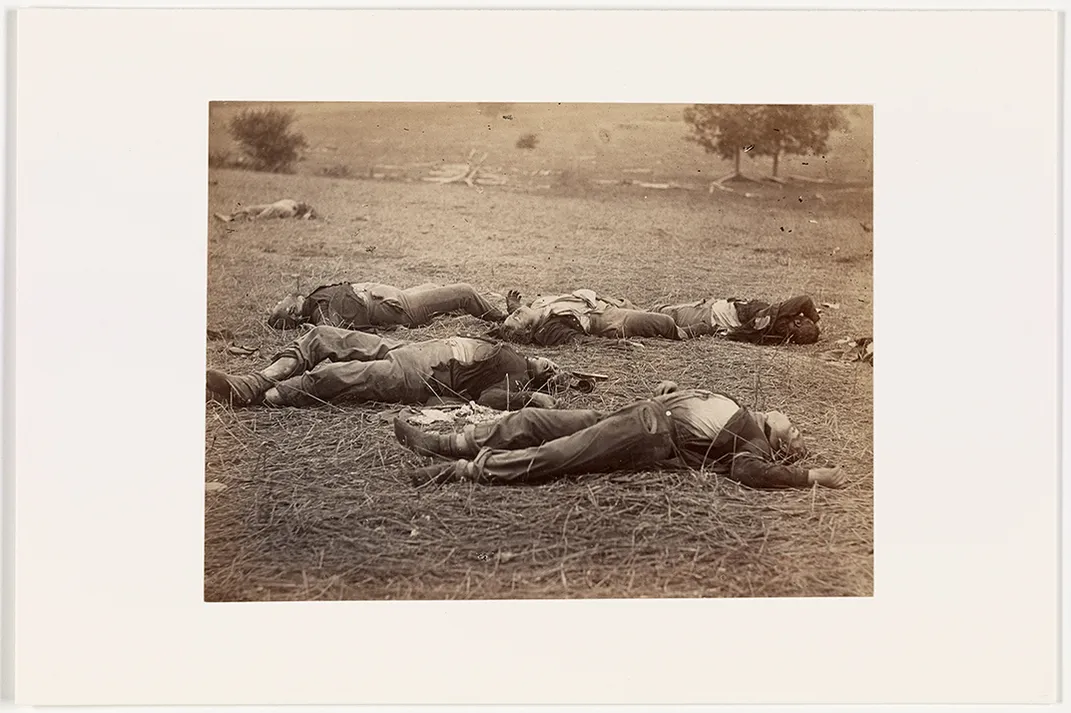

On January 31, Scafidi will join me at the National Portrait Gallery, where I serve as the senior historian, though I, too, am a poet. We will read our own work, and several from other poets, in the galleries of the exhibition, “Dark Fields of the Republic: Alexander Gardner Photographs.”

Scafidi and I have both engaged themes that directly or indirectly bear on the subjects of Alexander Gardner’s photographs, including the portraits of Abraham Lincoln or the images of the dead at Antietam and Gettysburg.

I asked Scafidi how he came to write about Lincoln and his answer was surprising, referencing not the public career or the character of the man or any other externals, but something deeply personal: “As a young father I was frightened of my children suddenly dying. I was obsessed by this fear.”

Coincidentally reading about Lincoln, he found the 16th president’s ability to overcome grief following the death of two of his sons to be profoundly admirable. Steve offers an arresting image to depict Lincoln’s adroit skill at managing the two sides of his life, his public career and his private loss: “It was heroic to suffer his grief and also lead the country through the war. It was as if a man performed successful brain surgery while being attacked by a dog.”

Scafidi was raised and still lives near Harpers Ferry; he works as a woodworker since poetry itself can’t pay the bills (most poets teach). Of course, this is John Brown’s territory, as is the Bloody Kansas, where Brown got his start on what historian Sean Wilentz has called his career as an anti-slavery terrorist.

“Many people in Virginia and West Virginia still see him more as a terrorist than a freedom fighter,” says Scafidi. It was Brown’s assault on the armory at Harpers Ferry—an attempt to raise a slave rebellion—that lit the long fuse leading to war between the North and the South. John Brown, he says, “is still the wild ghost of that place.” Weird John Brown, as Melville called him, is surely close to being the most complicated and complex figure in American history.

Scafidi explores the violence of mind and body in Brown—the radiating power of that all-consuming will that lives on in Brown; from his poem “The Beams,” even dead, his eyes were still “hard and wild/to see—like two slender crimson laser beams.”

The duality of John Brown: can good come of violence? The duality of the poet: a woodworker (and farmer) who writes verse. Of his two professions, Scafidi writes:

The cabinet-work is physical and the writing is mostly invisible. The cabinet-work brings me money and the writing brings me peace. The only true intersection of these two vocations I find is the lathe. On the lathe a piece of wood spins so quickly it blurs and into this blur you set a chisel and carve shapes by hand. On the page words come furious and whir at me in rhythms I find and shape by ear. Poetry and the lathe both have a similar magic.

A nice image—one thinks of Ezra Pound’s tribute to Walt Whitman as having broken the “new wood” of modern poetry, and that it was there for the carving.

My profession as an historian and my avocation as a poet are closer than the worlds of wood worker and poet. I work only in words, but there is a boundary line I have been reluctant to cross. I have consciously resisted writing “History” poems because they seemed too close to my “day” job: instead, I write poetry as a diversion.

But as I worked on the show “Dark Fields of the Republic,” Steve Scafidi’s poems helped me to see that my work could complement my poetry. There was no reason why I couldn’t address the past as a poet as well as a curator and historian. In the end, it all comes down to the whirling world of words—and making sense of ourselves by addressing the past.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/David_Ward_NPG1605.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/David_Ward_NPG1605.jpg)