A Night in the Forest Capturing Bats

Our intrepid reporter joins tropical bat researchers in the field one night and gains some appreciation for their fangs

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/3d/b4/3db4bbe9-ebff-4355-a353-496325b6c6f2/bat.jpg)

Stefan Brändel lives on a big island in the middle of the Panama Canal and spends his nights catching bats. Part of a small group of German scientists studying disease transmission in tropical forests, he hikes deep into the island's thick vegetation three to four evenings each week to collect data by snaring the creatures in long nets secured between trees. The work lasts until early morning, but Brändel, a doctoral student at the University of Ulm, is indefatigable—he really likes bats.

“I love diversity, and bats are a super diverse group of mammals, with a few thousand species worldwide, and 74 here on this island in the neotropics,” he told me a few months ago, when I visited the island, named Barro Colorado, to see one of the Smithsonian Tropical Research Center's research outposts, a cluster of labs and dorms on the forest's edge where he stays with other scientists throughout the year to study the island's protected flora and fauna.

“And they are cool animals,” he added. “That's the most convincing part.”

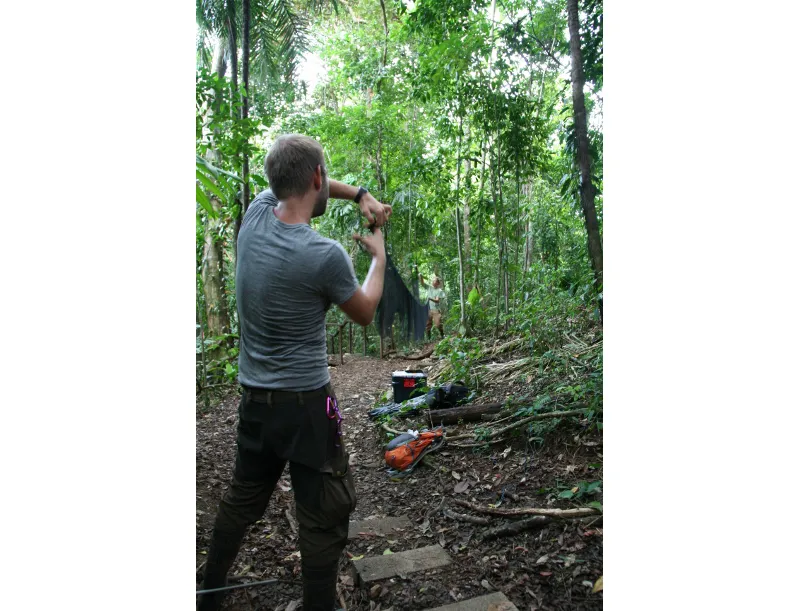

Brändel had agreed to take me along for a night of bat catching, so I met him by his group's lab a little before dusk, and we marched into the forest wearing mud boots and headlamps. (Brändel and his colleagues often travel by boat to more remote spots on and around the island, but an ominous weather forecast forced us to stay close to the research buildings.) While we still had sunlight, Brändel and another doctoral student pitched a few nets, each about 36- by 15-feet, over well-worn paths through the trees. Bats don't pay much attention while flapping over these paths because there aren't usually any obstacles, Brändel explained, so they're easier to snag.

The most exciting part of bat catching—or “filtering the air,” as Marco Tschapka, a professor from the University of Ulm who heads the team on Barro Colorado Island, likes to call it—is that you never know what you're going to get, the group agreed. Some nights they catch no bats, other nights they catch many; Brändel recently had hit a personal record of 80. When the sun set on the island and a couple squeaking, squirming little fur lumps quickly popped into our nets, he said we were in for another good night.

Up close, the tropical bat species we caught were an unsettling mix of adorable and repulsive. While all I wanted to do was scratch their fuzzy bellies and flick their leafy noses, their nightmarish fangs showed me exactly what would happen if I did. Brändel untangled each captive with care, pinning its wings together on its back with his fingers to prevent escape and to avoid nasty bites. The bats, who were far from happy, belted out squeeze-toy distress calls and chomped viciously on whatever came in front of them.

“As it cries, it's angry. It's not suffering,” Brändel said, after I had asked him if he worried his research was mistreating the animals. “Most of the species are really tough guys. Yes, you harm them in their way of living, you entangle them, but you have to treat them with respect.”

Ultimately, the benefits of enraging a small fraction of the world's bat population outweigh the consequences, Brändel and his colleagues agree. The broad point of their research is to see if human intrusion might be encouraging the spread of diseases between species in tropical forests by upsetting longstanding ecological balances. Scientific studies elsewhere have already shown that intact forests provide a natural buffer against disease outbreaks by nurturing a diversity of animals, insects and pathogens, which prevents any single disease from gaining prominence in the community. Brändel now wants to see if this same “dilution effect” applies to bats on Barro Colorado and its surrounding forests.

“What we hope to see is that in the plots [of forest] which have a higher anthropogenic influence, the ones that are the most degraded, there are fewer bat species, but a greater abundance of the species that survive, so they interact more and the prevalence of diseases is higher,” he said. “If the prevalence within a specific species is higher, then the risk also could be higher for transmission to another species.”

If Brändel's research shows evidence of this hypothesis, his work will add to the science community's already-strident call for us to take better care of the world's forests. By regulating construction and logging better and cracking down on poaching, the hope is that preserving forest diversity would prevent emerging diseases from hopping between species and possibly even eventually entering the human population.

To begin to understand how diseases spread throughout Barro Colorado's bat communities, Brändel's group first is simply gathering as much information as they can about the bats. “When you're talking about viruses, it's not enough just to go out, fish for viruses, look at whatever you find, and then declare the upcoming end of humanity because you found a virus,” Tschapka, the lead researcher, told me. “You need background information. And you need an idea about the ecology of viruses. What conditions favor the spread of viruses? Which conditions keep abundance and prevalence of viruses in hosts low? Without this information, you cannot say anything at all.”

After untangling the angry bats from his nets, Brändel dropped them into tiny drawstring bags, which he then hung on the nearby branches. After an hour or so of trapping—we netted about 20 bats, which was good considering we only used half the number of nets as usual—he and another doctoral student gathered the bat bags, set up a mini camp of science-looking equipment and sat on the ground to begin data collection, the part that keeps them up late. For each bat, they did the following: record species, sex, general age, location caught, forearm length and weight; collect tiny insect parasites from their body and store them in a vial; scrape a tissue sample from a wing for genetics information; swab for fecal samples (those go in a vial, too, and later are frozen); and take blood samples.

After Brändel had walked me through this data collection process, he and Hiller fell into a steady rhythm. As I sat off to the side, listening to frogs call in the forest and letting my eyelids droop, they worked tirelessly, lost in a zen state of extending measurement instruments, passing vials and making little comments to the bats.

“There's this excitement in your body,” Brändel said of the catching, especially when it's done alone. “You know what to do, so the work keeps me calm, but you have this form of adrenaline going, because you have to be very careful with everything, or very focused on it. That's what I love, really, the feeling inside, which is so super nice. I would not change this to any other thing.”

Besides encouraging better care for bats' habitats, he said he'd also like his research to improve bats' reputation. “A lot of people think all bats are vampires, all bats are bad, we have to kill them,” he told me. “The thing is, you have to see them. If you have them, and you handle them, and you look at their nice stripes and you know that is a fig eating bat, then they are just nice. They are cute animals.

"Part of the reason we study bats is to help people understand them,” he said.

The data collection took about two hours. After processesing each bat, Brändel unpinched their wings to let them go. The final one he studied was a rare catch: Phylloderma stenops, known as the "pale-faced bat." Its tan fur and pointed, ridgy ears were indeed attractive. Tschapka joined Brändel and Hiller to say goodbye to the creature, and they gently passed it around, each holding its puggish face close to his own for one last inspection. When they released it, the bat disappeared shrieking into the forest.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/paul-bisceglio-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/paul-bisceglio-240.jpg)