Celebrate Dino Month With Three New Dinosaur Books

From PhDs to 4th graders, something for everyone

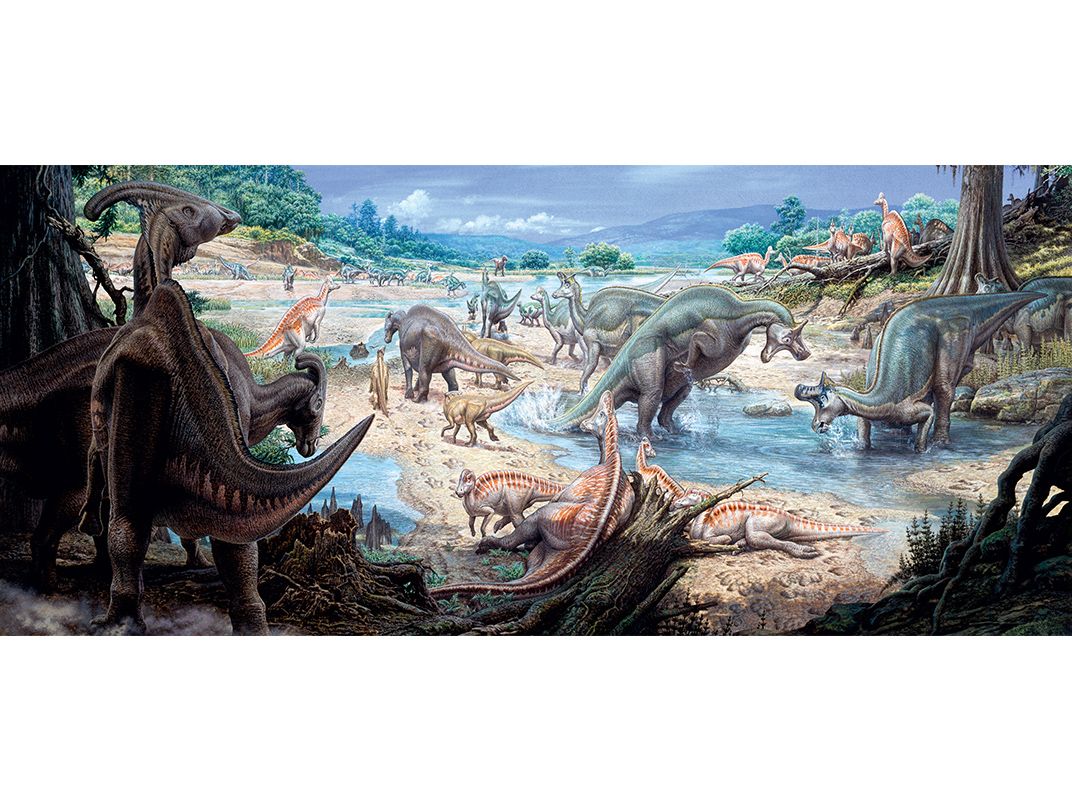

October is International Dinosaur Month and three books out this month from Smithsonian Books cater to dino lovers of all ages—each with a different approach to understanding these Cretaceous critters.

Think of every science news story that has been published over the past few years, busting yet another myth about dinosaurs.

Dinosaurs: How they Lived and Evolved is what serious aficionados have been waiting for. It's all here—anatomy, behavior, evolution and diversity—in this comprehensive study.

Paleozoologist Darren Naish (author of the popular blog, “Tetrapod Zoology”) and Paul Barrett from the Natural History Museum, London, teamed up to author one of the most up-to-date scientific sources of the moment.

“Dinosaurs” is written at an advanced level suitable for readers with backgrounds in ecology, biology or other life sciences. Whether you are a biology student looking to expand your range or a well-informed enthusiast with the desire to catchup on the state of current research, there is something here for you.

During his years of blogging, Naish has created a whole new audience of dino lovers. He pens exuberant articles about wildlife from hairy frogs to stegosaurus. His style has grabbed the interest of many a casual reader and pulled them into the academic worlds of field biology and paleontology whether or not they even hold a college degree. If you have been reading Tetrapod Zoology for a while then you are probably familiar with the concepts and terminology necessary to understand his recent book, which is well-illustrated with 200 color images including works of art and photos of fossils, as well as graphs and computer reconstructions.

A number of myths are laid to rest by Naish and Barrett. The theory that grasses were not part of dinosaurs' ecosystems or diets is finished. Sauropodomorphs could not have walked on all fours. And it you haven't gotten the memo yet, Jurassic Park had it all wrong. Most theropod dinosaurs probably had feathers. Including the tyrannosaurs.

Naish and Barnett hit just about every aspect of dinosaur biology that can possibly be addressed through what we have of the fossil record. Ontogeny, respiration, digestion, swimming, sex and coprolites. If you want more than what you'll find in here then you'll probably have to go back to the scientific papers describing the research that the authors draw from. And that would be difficult, because the one important element that this book lacks is footnotes with a complete bibliography.

Giants of the Lost World: Dinosaurs and Other Extinct Monsters of South America by Donald R. Prothero takes an unusual approach to writing about the extinct wildlife of the cretaceous, focusing on their evolutionary history in South America.

It is an especially rewarding area of study because the South American continent became isolated from other landmasses about 100 million years ago. For a sense of scale, dinosaurs became extinct roughly 65 million years ago. But small, early mammals had already arrived.

Dinosaurs on the South American continent evolved in their own unique directions. For example, the southern continent never had any dinosaurs that were closely related to triceratops, but it did have carnotaurus, the swift predator with bull-like horns.

South American birds and mammals also evolved in unique directions compared with Eurasia and North America, which were often connected to one another by land bridges. The continent possessed strange mammilian giants like the glyptodonts and the rhino-like toxodon. The apex predator even in the 'age of mammals' was the flightless terror bird, reaching almost ten feet in height.

Prothero takes an unexpected turn by pulling back the curtain on the controversy over the mass extinction event at the end of the Cretaceous Period (which included the loss of all dinosaurs other than birds). The fact of a massive asteroid impact is settled science, but Prothero describes other events from around the same time that may have contributed to to the mass extinctions. He includes the heated debates—and insults—between scientists from different fields over exactly what killed the dinosaurs.

The author is not afraid to take to task scientists who hold fast to certain older ideas about dinosaur evolution, writing of the theory that birds are taxonomically dinosaurs (again, this is settled science), “only a handful of scientists, mostly older-generation ornithologists unfamiliar with the fossils and unwilling to change their old notions, still resist this mountain of evidence.”

The mountains of evidence are indeed compelling for much of what Prothero describes, but unfortunately this is another book lacking the footnotes a curious reader craves, making it difficult for to easily examine the arguments in support of many of his points.

Giants of the Lost World includes quite a lot of the history of scientific thought and research in South America. This introduces human characters and gives the book a sensibility somewhat reminiscent of Simon Winchester's Krakatoa. It is certainly less of a text book than Naisch and Barrett's new work. Giants of the Lost World will be more accessible to the educated lay reader than Dinosaurs is. Anyone with a basic grasp of high school biology can get something out of this book.

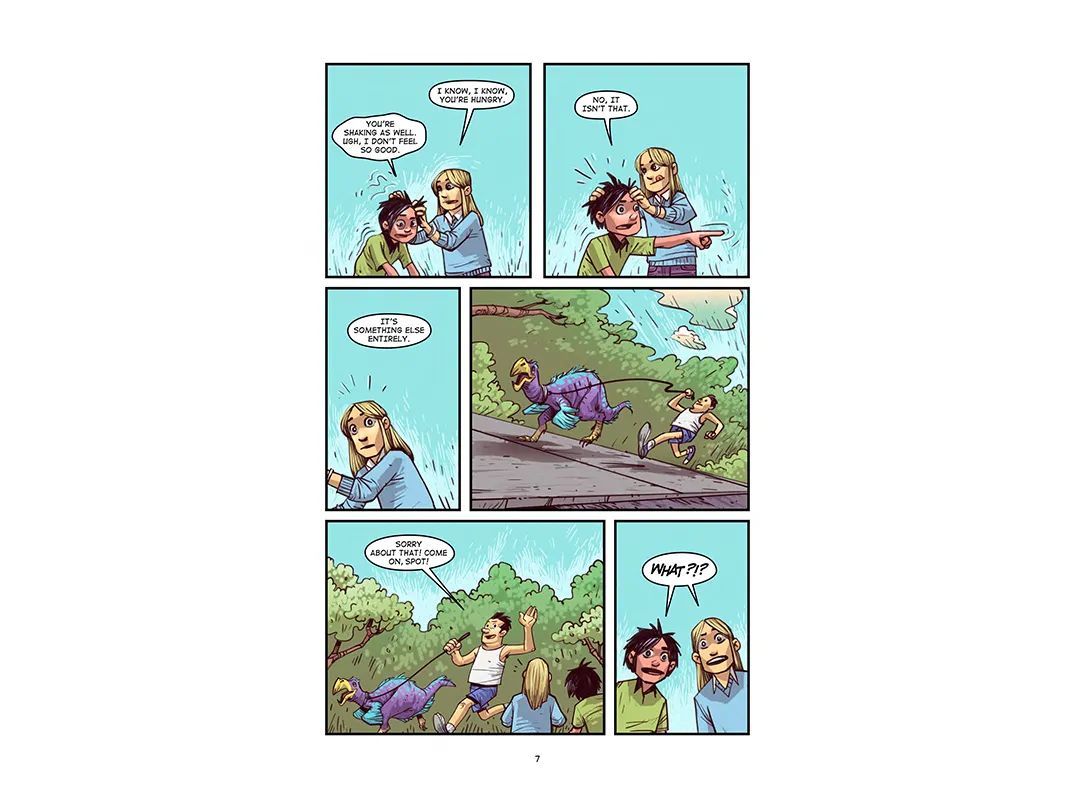

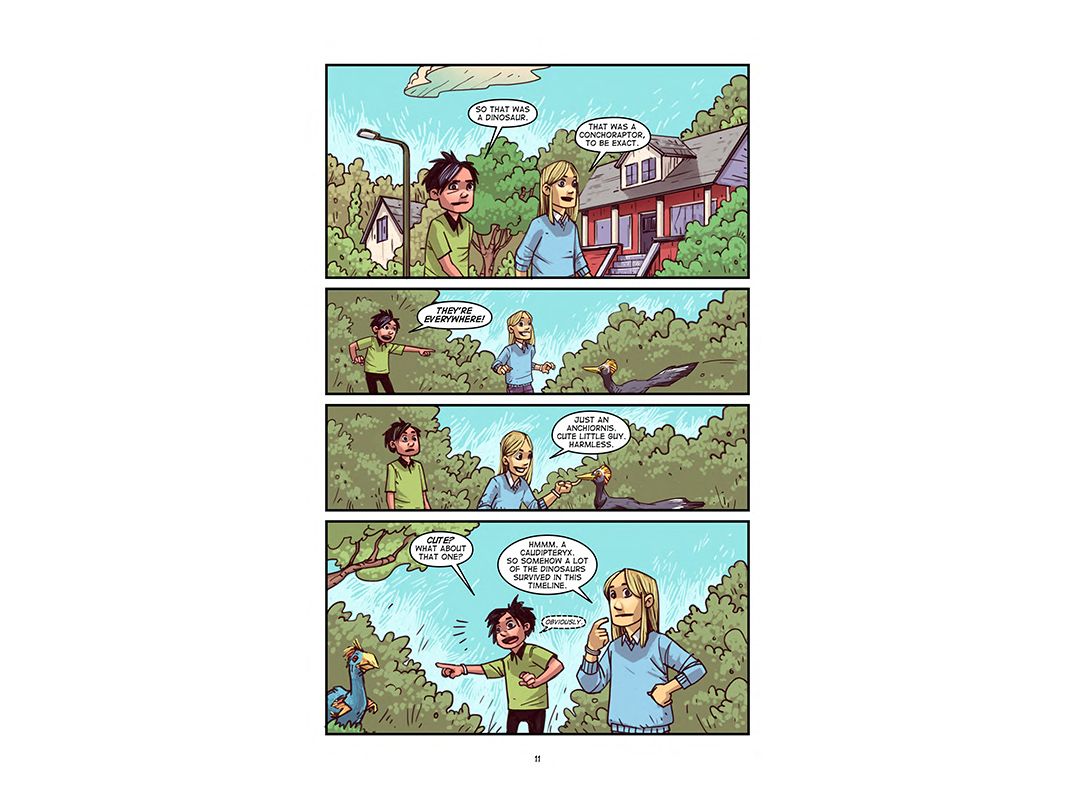

The graphic novel Claws and Effect is the second in the childrens' series, “Secret Smithsonian Adventures.” A group of kids are time travelers, correcting disturbances in the historical time line made by other people who have misused a time machine. In this volume, the young adventurers find that small dinosaurs (other than birds) are suddenly a common form of wildlife in present-day Washington D.C.

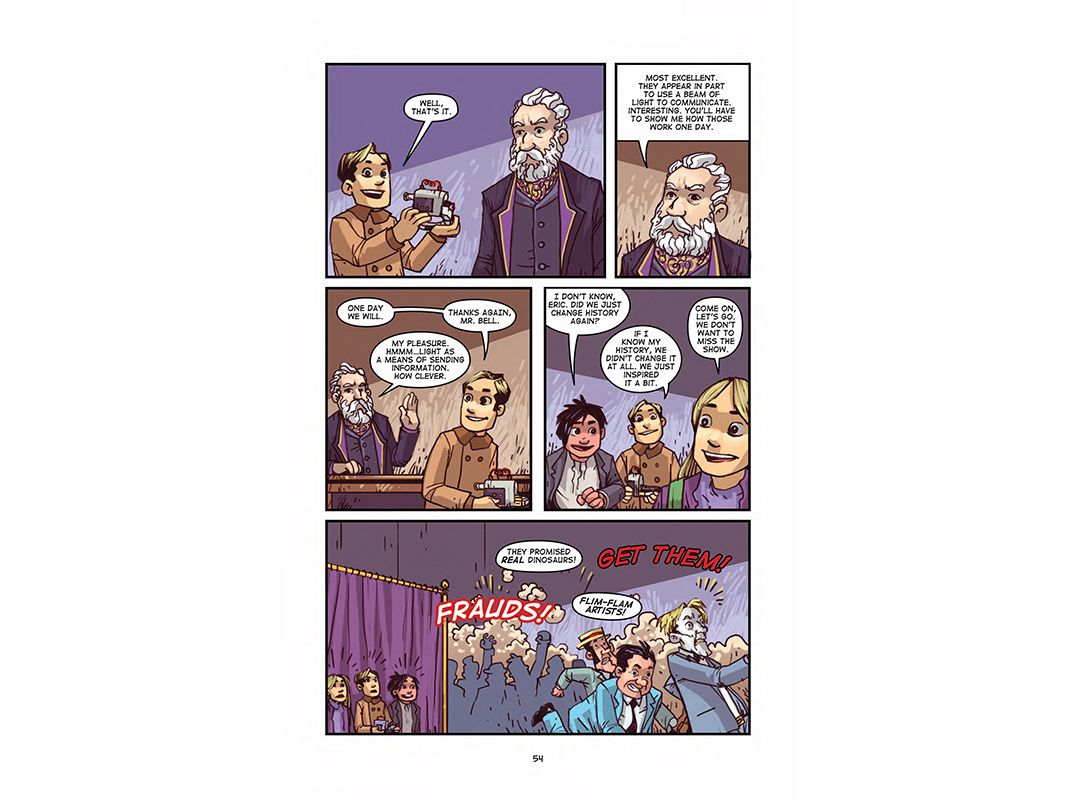

With a pet dinosaur along for the ride, they travel to the 1858 World's Fair and meet William Parker Foulke, discoverer of the first largely complete dinosaur skeleton known in North America. Alexander Graham Bell steps in to help with an unexpected repair to a time machine.

Claws and Effect is reasonably accurate in its history and science, though nitpickers might disagree. The takeaway here is a much better informed young reader in history and the sciences.

I asked a nine year old to read Claws and Effect and report back. Overall, he gave me a thumbs up but had difficulty reading a 1980s style computer font used to display the dialogue with a particular character.

It's amusing to think that to people born in the last decade a cretaceous-era creature is more familiar and less mystifying than a decades-old retro typeface.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/JacksonLanders.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/JacksonLanders.jpg)