Celebrate National Salad Month with Rare and Historic Books that Include Your Favorite Leafy Greens

A Smithsonian librarian journeys through history and time on a quest to explore salads throughout antiquity

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/0f/12/0f129cc5-7134-4d39-8583-ab92f97765c8/acetariadiscours00evel_0001-wr.jpg)

The common, if well-worn phrase, "My salad days, when I was green in judgement," first appeared in Shakespeare’s Antony and Cleopatra of 1606. At the end of Act One of the play, recalling a youthful affair with Julius Caesar, Cleopatra refers to a time of innocence, silliness or indiscretions. Since May is National Salad Month, let us celebrate the greens by looking at the work of another Englishman, John Evelyn (1620-1706). His Acetaria: a discourse of sallets, printed in London in 1699, was the first book devoted to salads.

Salads were eaten in antiquity (that Shakespeare knew what he was writing about), attested to by Evelyn’s curious title. He borrowed it from Pliny the Elder’s Natural history (Book XIX): “Formerly, the products of gardens were most approved, for they are always ready for use, and speedily prepared. They require no fire, and therefore, fuel is economized. Thence they were called acetaria; they are easily served up.” Evelyn’s definition: “We are by Sallet to understand a particular composition of certain Crude and fresh Herbs, such as usually are, or maybe safely eaten with some Acetous Juice, Oyl, Salt.” That is, a vinaigrette.

According to Alan Davidson’s Oxford companion to food: “Salad, a term derived from the Latin sal (salt), which yielded the form salata, ‘salted things’ such as the raw vegetables eaten in classical times with a dressing of oil, vinegar or salt. The word turns up in Old French as salade and then in late 14th century English as salad or sallet.” There are references in Chaucer and other early English writers in England to lettuce (“letows”) as well as cress, radish, savory, spinach, fennel, mustard, parsley and various other herbs. The sort of plants and vegetables we would use in today in composing a salad. Evelyn lists seventy-three possibilities (his “Furniture and Materials”) for ingredients.

Evelyn was a scholar, expert on sculpture and architecture, diarist, gardener and designer, translator of garden books, and a founding member of the Royal Society of London, formed “for improving Natural Knowledge.” He was a gentleman of many and varying accomplishments. Convincing his countrymen to eat raw greens and mostly vegetables for health (“People, who to this Day, living on Herbs and Roots, arrive to incredible Age, in constant Health and Vigor”) was not one of his successes. Boiled vegetables remained the preference for ages.

Sadly, there is not a first edition of Evelyn’s Acetaria: a discourse of sallets in the Special Collections of the Smithsonian Libraries. But the nearby Library of Congress has an astounding copy: it was presented by the author to Sir Christopher Wren. In addition to Evelyn’s handwriting on the title page and preceding leaf, there are 13 lines on the cooking of carrots and cucumbers, serving as the author’s own personal addendum for the architect (both worked on the rebuilding of London after the Great Fire of 1666). In the Botany and Horticulture Library in the National Museum of Natural History is a reprint of Acetaria, published by the Women’s Auxiliary, Brooklyn Botanic Garden, in 1937. The University of Toronto Fisher Library copy is also available via the Biodiversity Heritage Library, viewable to all here. Evelyn’s “discourse of sallets” reappears in its entirety in the fourth edition of Sylva, his best-known work, in 1706.

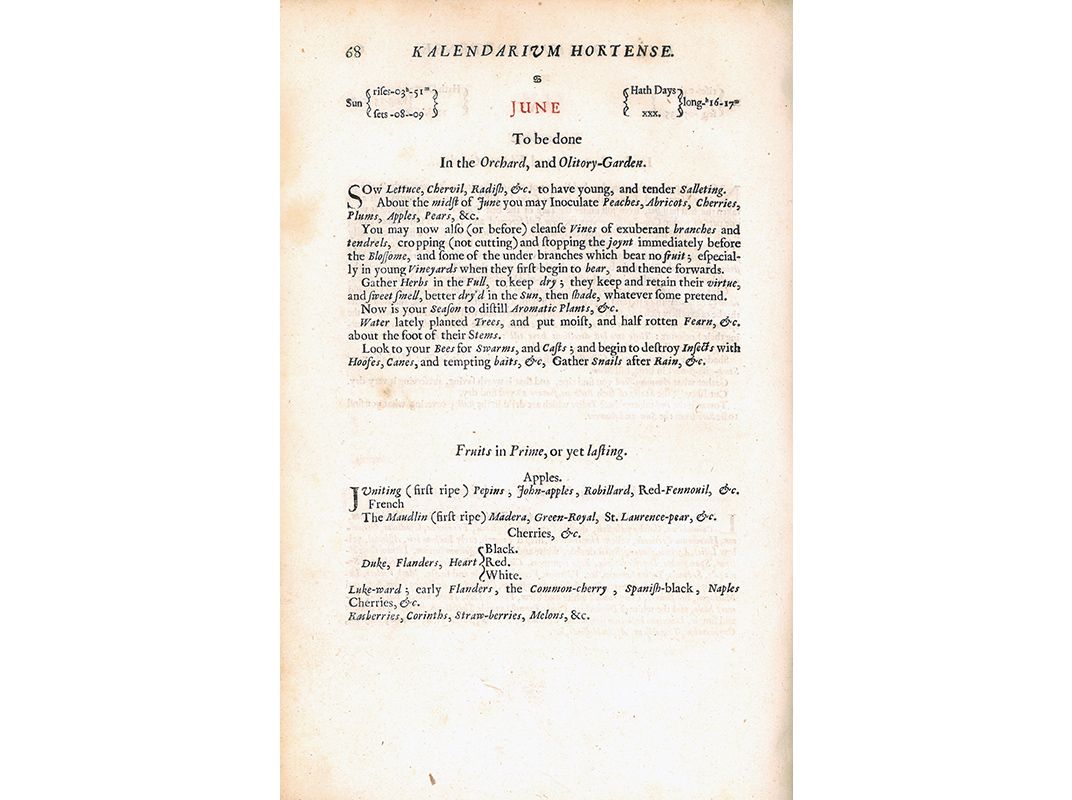

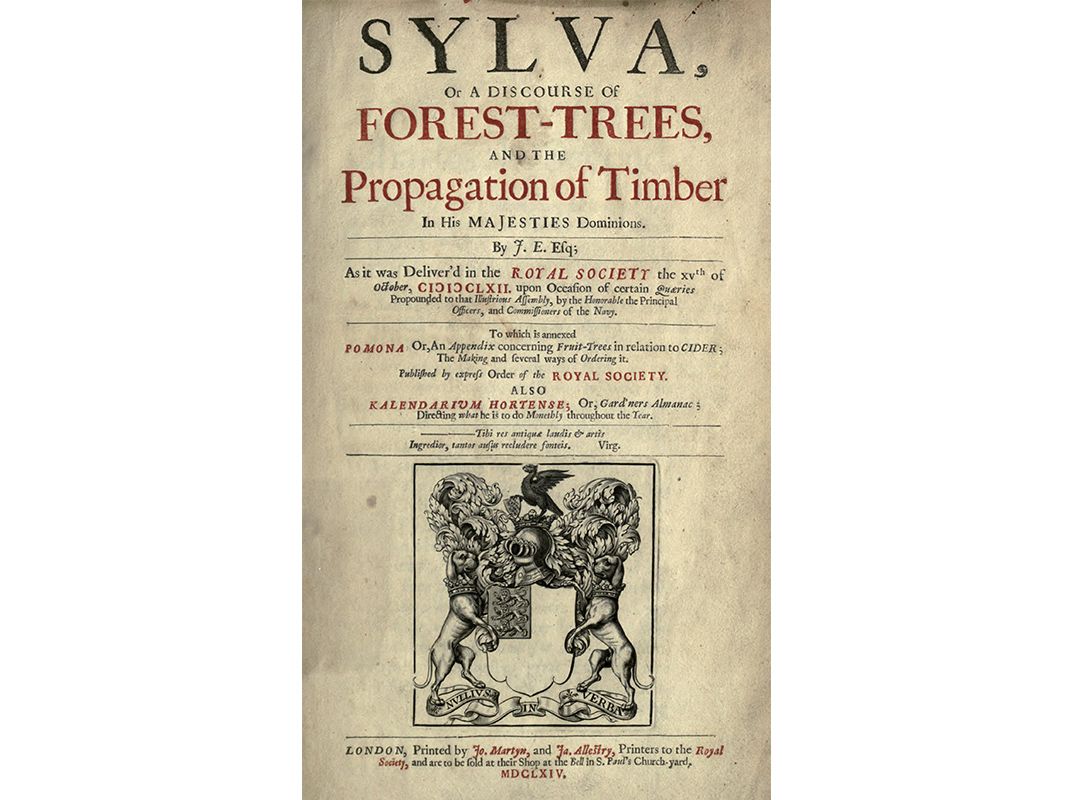

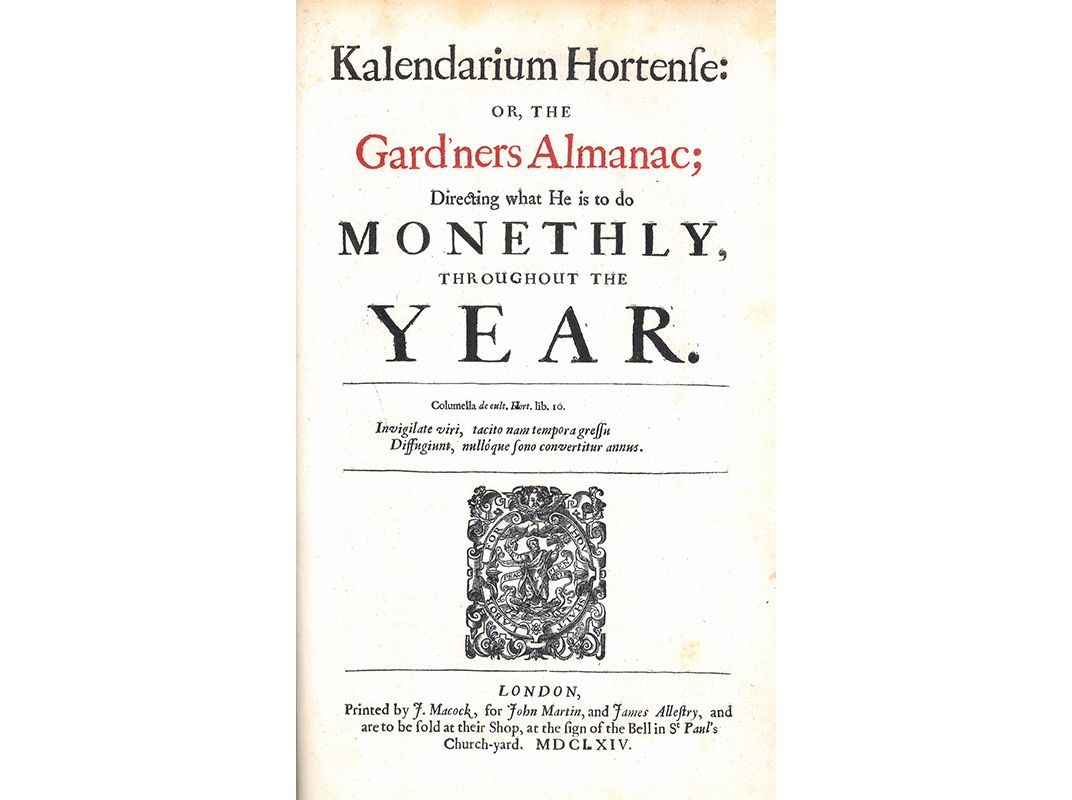

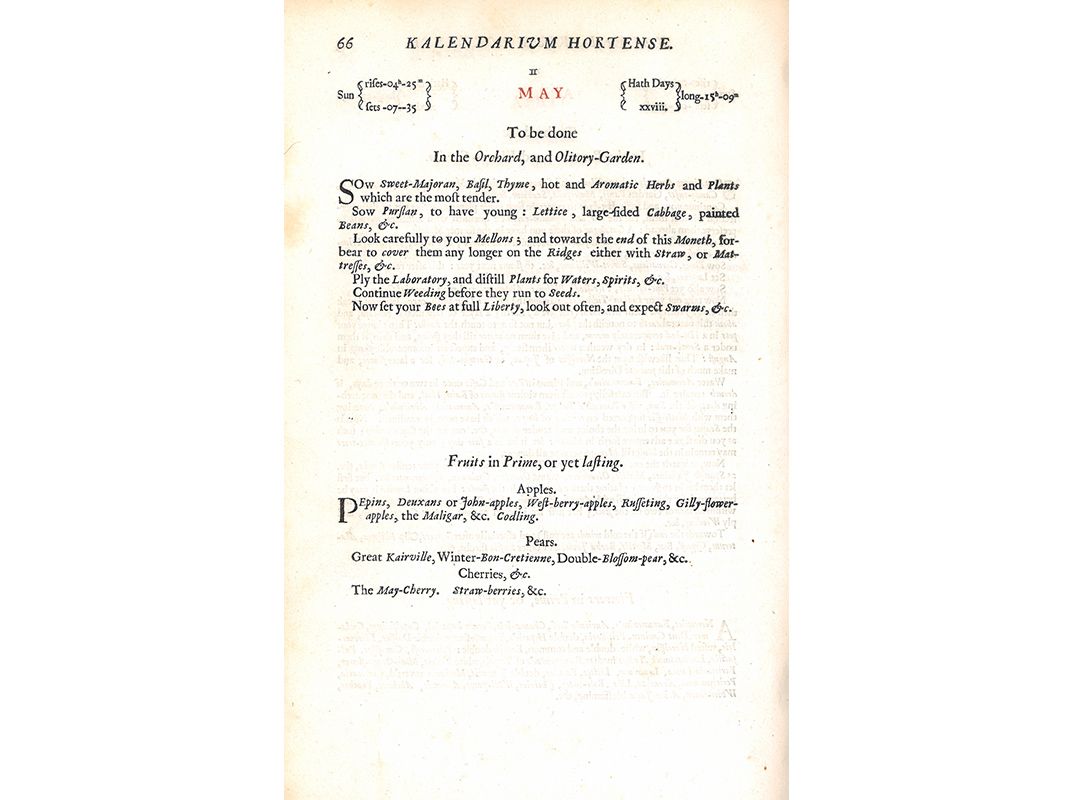

The Dibner Library does have the first edition of Sylva, or, A discourse of forest-trees, published by the Royal Society in 1664. There was concern over the declining tree canopy in England at the time, and the diminishing supply of timber for ships of the Navy. In this earlier treatise, after discourses on forestry, fruit trees and the making of cider, the Evelyn lays out a calendar with practical advice for the planting of vegetables in a section entitled “Kalendarium hortense, or, The gard’ners almanac: directing what he is to do monethly throughout the year.” This almanac was written for the author’s great unpublished, encyclopedic Elysium Britannicum. And it is here we find our salad months

The introduction lays out the importance of labor: “A Gard’ners work is never at an end: It begins with the Year, and continues to the next: He prepares the Ground, and then he Sows it; after that he Plants…”. January is for preparing the ground for spring planting, as well as the sowing of “Chervil, Lettuce, Radish, and other (more delicate) Salletings; if you will raise in the Hot bed [greenhouse].” The instructions for May are to “Sow sweet Majoran, Basil, Thyme, hot and Aromatic Herbs and Plants which are the most tender. Sow Purslan, to have young; Lettice.”

Whether or not you tend a garden, I encourage you to raise a salad fork, salute Evelyn, and celebrate a fresh, new green season. Happy Salad Month.

A version of this article by librarian Julia Blakely was originally published on the Smithsonian Libraries blog, "Unbound," a compendium of rich resources for book lovers young and old.