A Changing Mecca Is the Focus of the First U.S. Exhibition to Feature a Saudi Artist

The works of Ahmed Mater at the Sackler examine the stark collision of the sacred and profane

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/19/58/1958f615-fe91-4226-961c-fd692d5b6e84/crisisweb.jpg)

In the year he spent living in Mecca, physician-turned-artist Ahmed Mater watched hotels shooting up around the Grand Mosque. He also trained his camera on both the workers, who came from all over the Muslim world to help construct the new city, as well as on the ways that Mecca’s history was being erased to make way for the new city.

Mecca is inaccessible to non-Muslims, and so the offering of an unprecedented view of the city through the eye of an artist is what Mater brings to his audiences. His photographic works and videos are on view through September at the Smithsonian’s Sackler Gallery in “Symbolic Cities: The Work of Ahmed Mater.”

The show is the first solo museum appearance in the country for a contemporary Saudi artist, says Carol Huh, the Sackler’s assistant curator of contemporary Asian art. “We’re very proud of that.”

Trained as a physician, Mater—who was born in the village of Tabuk in northern Saudi Arabia in 1979—arrived at photography by way of the X-rays he relied on for his medical practice. In fact, he integrated X-rays into his first artworks. And he has served as one of the many doctors on call during the annual Islamic pilgrimage to Mecca, known as the Hajj.

Although he became a full-time artist a few years ago, Mater believes that drawing on his background, combines both scientific and subjective ways of looking at the world. He approaches photographing cityscapes as a doctor would.

Having trained as a physician, Mater, who was born in the village of Tabuk in northern Saudi Arabia in 1979, arrived at photography by way of the X-rays he relied on for his medical practice. Although he became a full-time artist a few years ago, Mater believes that drawing on his background, combines both scientific and subjective ways of looking at the world. He approaches photographing cityscapes as a doctor would.

“For me, it’s an inspection,” he says.

His work, he adds, is also activist, or as he puts it, “art with intervention” rather than simply capturing a moment.

In the year he spent living in Mecca, Mater watched hotels shooting up around the Grand Mosque. He also trained his camera on both the workers, who came from all over the Muslim world to help construct the new city, as well as on the ways that Mecca’s history was being erased to make way for the new city.

In his 2011 to 2013 photograph Between Dream and Reality, several figures appear in the extreme foreground set against an enormous poster depicting an imaginary rendition of how the Grand Mosque and its surrounding might look in the future. The mosque’s spires are juxtaposed with not-yet-built skyscrapers in the background. It has a clean, modern look—almost like Las Vegas—but it literally masks the construction project that is happening behind it, which is dismantling historic Mecca architecture. The “dream” is destroying the reality.

“For me, it’s an inspection,” he says.

His work, he adds, is also activist, or as he puts it, “art with intervention” rather than simply capturing a moment.

In his 2011 to 2013 photograph Between Dream and Reality, several figures appear in the extreme foreground set against an enormous poster depicting an imaginary rendition of how the Grand Mosque and its surrounding might look in the future. The mosque’s spires are juxtaposed with not-yet-built skyscrapers in the background. It has a clean, modern look—almost like Las Vegas—but it literally masks the construction project that is happening behind it, which is dismantling historic Mecca architecture. The “dream” is destroying the reality.

The weathered nature of the poster, which lends it the look of an old photograph, impressed upon Mater the way that “the dream will meet the reality of life here … I thought Mecca is going to look like this in the future.”

Although millions of visitors come to Mecca for Hajj, there are also one million people living in Mecca. “It’s a living city. It’s not just about the pilgrims,” Huh says, comparing the phenomenon of tourists overshadowing residents in Mecca to Washington, D.C. “There are natives,” she says.

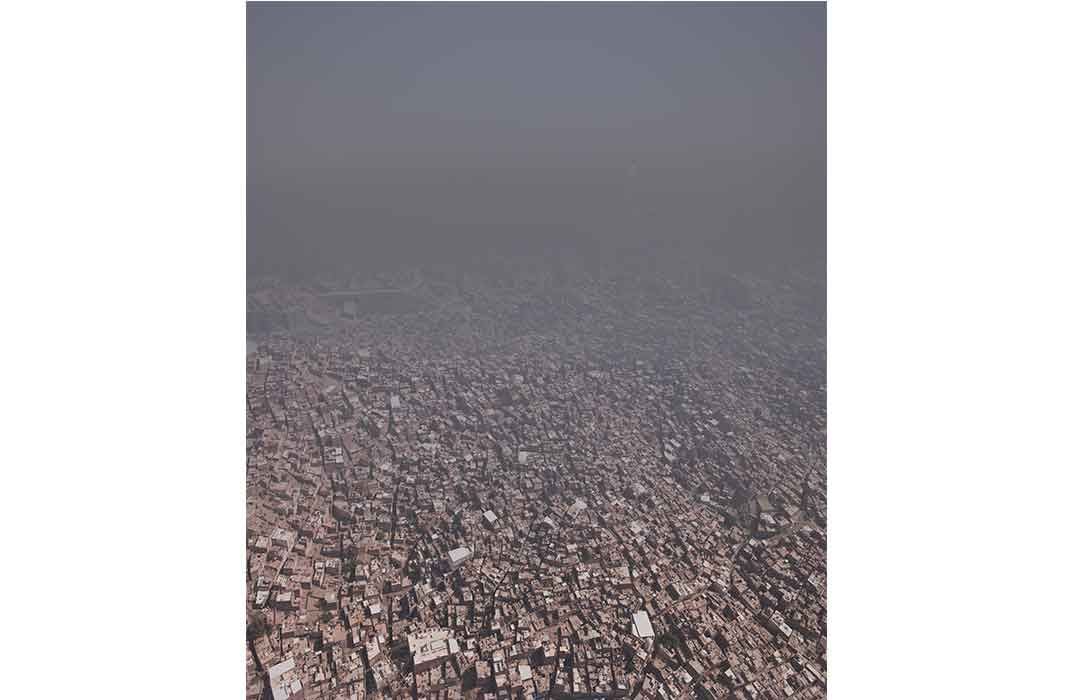

Many of those residents are immigrants who live in densely-populated areas of the old town, such as the ones that Mater photographs in the 2012 From the Real to the Symbolic City, one of two works of Mater’s held in the Sackler’s collections. Peeking through the haze above the homes is the Fairmont Makkah Clock Royal Tower, which represents the symbolic city. Mater hadn’t initially noticed it.

The layering of Mecca that Mater teases out is perhaps most pronounced in the 2013 Nature Morte—the second piece from the collections. It presents a view from within the Fairmont hotel of the main sanctuary of the Grand Mosque and the Kaaba, a shrine that is the most sacred site in Islam. But the frame of the shot is the interior of a $3,000-a-night hotel room, with a plate of fruit on a table and a comfortable chair. Pilgrims who come on Hajj wear all-white as a great equalizer, and everyone, poor or wealthy, is supposed to be the same, and yet, as Mater’s camera shows, some pilgrims are more equal than others.

Not only do the wealthy get to stay in Mecca in five-star hotels, while millions of other pilgrims squat in tents, but those with great means also can skip lines at the various pilgrimage sites. The photograph shows how private spaces are taking over public spaces in the holiest of Islamic spaces. “It squeezes the public space,” Mater says.

For those who don’t get to skip the lines, a network of human highways defines many of the pilgrimage sites in Mecca. The 2011 to 2013 Human Highway shows throngs of pilgrims packed into tight spaces—their colored umbrellas are testaments to the sponsorship of mobile phone companies—many without hope of getting to the sparse emergency exits.

“People have actually died,” Huh says. In 2015, for example, more than 1,450 people, by some accounts, were killed in a deadly stampede during the pilgrimage.

At the center of the 2011 to 2014 Concrete Lapidation are three pillars, which have been extended to become walls to accommodate the massive crowds, against which the faithful cast 21 stones (seven per pillar) to symbolically cast out the devil. In Mater’s video Pelt Him! there are no worshippers depicted, but the hum of voices can be heard as the artist presents a close view of the stones hitting the wall.

“To take a video like this, you need a lot of licenses,” Mater explains. “It will take time.”

In his 2013 Disarm, Mater photographed views of Mecca being taken by surveillance camera within a military helicopter. In one image, a group of people illegally tries to enter Mecca without proper paperwork. Other views show the clock tower and the network of human highways. It is, the artist notes in an exhibition brochure, the city’s future: “a sprawling metropolis monitored from the skies, with an army whose mission it is to detect the undesired movement of illegal pilgrims navigating their way across the arid and inhospitable mountain terrain.”

“This is a perspective that is unique,” says Massumeh Farhad, the Sackler's chief curator and Islamic art curator. “He’s the only art photographer who uses Mecca as his subject.”

The Disarm views are radically different from the 2011 to 2013 Golden Hour, an enormous photograph of the Grand Mosque and the clock tower which Mater took from atop a crane. The cityscape is like a spring landscape, in which cranes— like the first flowers—begin to peek out of the earth. Mater devotes nearly half the image to the construction that is occurring all around the mosque.

While those involved in constructing the new buildings and hotels might rightfully note that the city needs to expand to safely and comfortably accommodate millions of pilgrims, critics worry about the cost of those expansions and wonder if the city can’t grow without preying on its history. Mater is among those who see loss. That’s how Huh sees things as well. “There are many layers of history, even visually, across the public spaces of Mecca where the historical references are clear, and those historical references are being erased,” she says.

In the 2013 video Ghost, Mater discovers the human element that had been missing in so many of the other views of Mecca. Walking southeast out of the city, he came across drummers at a wedding. He trained his video camera on one particular drummer, an immigrant from Africa to Mecca.

“For me, it was a big relief about what’s happening in Mecca with the construction. This is the human part that is missing,” Mater says.

Another human element emerged in the preview of the exhibition. Mater pulled out his phone to snap a photo of the installation of nine wooden slide viewers titled Mirage (2015), in which Mater layered, for example, a London street atop a desert landscape. The artist subsequently confirmed that this was the first time he’d seen the work-in-progress installed.

“Symbolic Cities: The Work of Ahmed Mater” is on view through September 18, 2016 at the Sackler Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mw_by_vicki.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mw_by_vicki.jpg)