Chuck Brown’s Guitar Drove the Musician’s Persuasive “Wind Me Up” Rhythm

The Godfather of Go-Go’s family recall how the musician crafted the innovative sound that would define a local tradition

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/5b/44/5b449094-c4ce-4549-8042-4c3ac1120bf8/chuckbrownguitar.jpg)

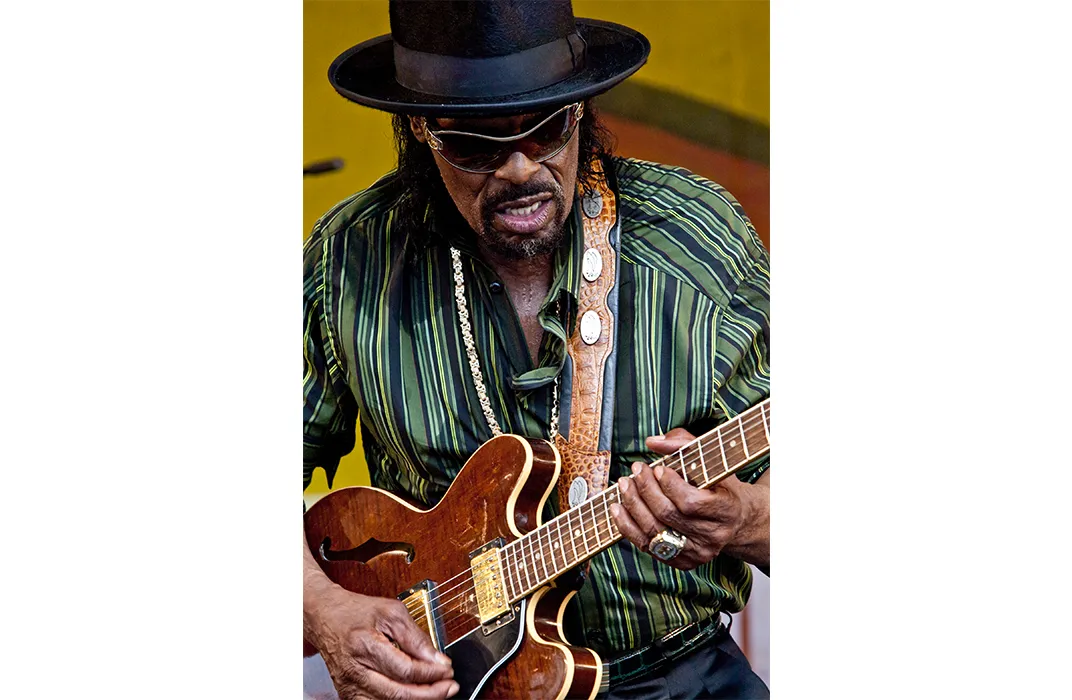

The flashy, hot pink velour interior of the guitar case gives a few hints of the instrument it holds and of the person who owned it. The 1973 Gibson Custom Shop Edition guitar belonged to the late Washington D.C. musician Chuck Brown, the Godfather of Go-Go music, a funky, polyrhythmic genre that Brown created.

The unique style of rhythm and blues was played beginning in the late 1970s in the city's African American neighborhoods and surrounding suburbs of Maryland and Virginia. The guitar and its case are now held in the collections of the Smithsonian's Anacostia Community Museum.

“Chuck Brown called that guitar Blondie,” says his daughter KK Donelson Brown, because of the Gibson's yellow wood color. Its case exemplifies the guitar player's raw charisma. Dressed always in his trademark dark glasses, suit and fedora, Brown kept alive the archetypal blues role of the "Hoochie Coochie Man." Nekos Brown remembers his father using the guitar in countless gigs throughout the 1980s and ‘90s. Wiley Brown, another of the musician’s sons, notes that his father when he was not gigging, was always strumming a guitar around the house. He recalls hearing his father picking at 5 a.m. “It was weird if there was silence,” Wiley Brown says. KK notes that sometimes Chuck Brown would play all night. “He practiced every night. He practiced so much,” adds Nekos, “it was hard to go to sleep without hearing that guitar. When I would go away to football camp, I wasn’t used to going to sleep without music.”

Born in 1936 in North Carolina, Charles “Chuck” Louis Brown moved to Washington, D.C. in 1942 and before his death in 2012, the Grammy-award nominee would have to his name the hit 1979 single “Bustin’ Loose,” and some 20 go-go, jazz and blues albums. Brown garnered such local affection and acclaim that the city, which had already named a street block Chuck Brown Way, would honor his legacy further in 2014, with the Chuck Brown Memorial Park.

A high school dropout who spent some of his teen years shining shoes, Brown developed his guitar skills at a prison complex in Lorton, Virginia, where he served eight years for shooting a man in what he always asserted was self-defense. There, he traded five cartons of cigarettes for a guitar that a fellow inmate made in the prison’s woodshop.

According to his daughter KK, Brown would pick up more guitar skills from D.C. bluesman Bobby Parker. But it was while he was playing with a local Hispanic band called Los Latinos that he observed how the energetic beat of the timbales and congas got the audience up and out of their seats, dancing to the beat. With his own band, the Soul Searchers, a group he founded in 1968, Brown later added that same Latin percussive tradition to the intervals in between the songs. And along with the jazzy percussion of the Grover Washington composition “Mr. Magic,” that the group frequently covered, Brown was on his way to developing his trademark tradition, a persuasively insistent dance beat.

A fan of blues, soul, gospel, jazz and funk, Brown’s band soon featured brass, a rhythm section and keyboards emphasizing the rhythm, which, in his words, just kept go-going. In an interview with the National Visionary Leadership Project Oral History Archive, Brown said that he also began doing proto-rapping at this point, engaging in call and response shoutouts over the percussion breakdowns. With his deep bluesy vocals, Brown’s call, recognizing a neighborhood or an individual, soon became a ritual hallmark of his shows.

George Washington University Professor Kip Lornell, who co-authored the book, The Beat- Go-Go Music from Washington D.C., says: “Percussion is at the heart of go-go, of course, but it doesn't speak to all of go-go's sound.” Referencing other stars of the genre, Lornell adds, “In addition to the horns used by Trouble Funk, E.U., and Chuck, along with Little Benny's and D. Floyd's distinctive vocals, there is also Mr. Brown's guitar. His guitar playing underscores that go-go's roots are in blues, jazz and funk. Chuck was always go-go. . . plus. He and his guitar always called out to remind us that the music he created represented D.C.”

Chuck and his band would play live multiple nights a week; and sometimes twice a night in multiple locations. Audiences clamored for him at the Black Hole on Georgia Avenue, the Panorama Room in Anacostia, the Masonic Temple on U Street and in Maryland at St. Mary's Church in Landover, as well as at the now defunct 18,000-seat Capital Centre arena.

After “Bustin’ Loose” hit number one on the R&B chart, and in the top 40 of the pop chart, Brown and the band toured the U.S., sometimes opening for Gladys Knight. In 1986 the band had a brief brush with crossover fame, when the film Good to Go, featuring go-go bands was released. In the late 80s and early 90s the group played gigs in Japan. KK notes that the fans there had memorized Brown's lyrics. Meanwhile at home, Brown would happily pose for photos with his local fans, who would chant with approval at all of his gigs, “Wind Me Up, Chuck, Wind Me Up,” meaning they were ready to dance.

Always a fan of multiple genres of music, Brown released go-go covers of “Day-O” long associated with Harry Belafonte, as well as the Muddy Waters' associated blues number “Hoochie Coochie Man.” And in the ‘90s, he released the album “The Other Side,” a series of blues and jazz vocal duets with Eva Cassidy. Performing in the studio as well as at the city’s Georgetown nightclub Blues Alley, Brown and Cassidy’s vocals conveyed a heart-touching, melancholy mood. These releases, like his 2011 appearance with the National Symphony Orchestra on the U.S. Capitol grounds, endeared him to some who were not hardcore go-go fans. Lornell observes that “Chuck as a guitar player is more important to his less-faithful fans, those who know a bit about go-go. A guitar signals more than go-go, perhaps a touch of R&B to soften that hardcore go-go sound,” he says, adding that the instrument can "invite in more timid listeners.”

Grammy winning rapper Nelly’s 2002 hit “Hot in Herre” sampled “Bustin’ Loose,” and the song was also heard in a Chips Ahoy TV commercial. A DC Lottery commercial featured Brown, wearing his signature suit, fedora and dark sunglasses and always with his guitar, delivering his familiar baritone octave chuckle. And at Washington Nationals baseball games, a portion of “Bustin’ Loose” is always played at every home run.

In 2012, the 75-year-old Brown was hospitalized with pneumonia. Months later he passed away from sepsis. At a four-hour memorial service at the Walter E. Washington Convention Center attended by thousands who came to pay homage to Brown who lay at rest in a golden casket, his band performed and others, including former Mayor Marion Barry spoke in tribute. Last August, when the Chuck Brown Memorial Park opened in Northeast D.C., hundreds turned out, again his band played. The park features a tribute wall with performance photographs and a timeline of his career highlights. It also includes a tall serrated metal sculpture by artist Jackie Braitman of Brown leaning forward, his microphone pointed to the crowd for their response, and of course featuring the musician’s iconic guitar.

Officials at the Anacostia Community Museum say they are currently exploring the prospect of a go-go exhibition. “We featured a small section on Go-go including Chuck Brown’s Guitar in our 40th anniversary exhibition ‘East of the River: Continuity and Change” says Portia James, supervisory curator at the museum. “Also Go-go music and a memorial tribute to the then-late Chuck Brown were a focus of the 2012 Smithsonian Folk Life Festival program “Citified: Arts and Creativity East of the Anacostia River,” which was presented in collaboration with the museum.”

The Beat: Go-Go Music from Washington, D.C. (American Made Music Series)