Civil War Photography Gets 3-D Treatment in New Exhibit at the Castle

Battlefields come to life using the stereoview technology developed on the eve of the Civil War

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/20120919112012Civil-War-150_Thumbnail.png)

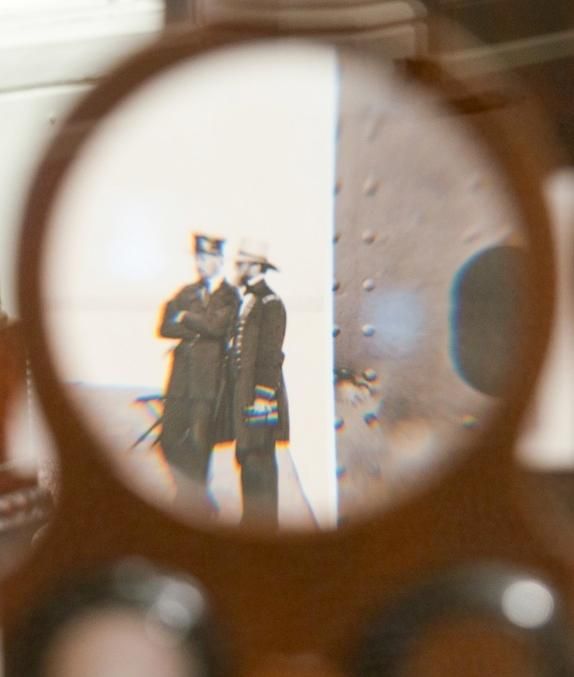

During the Civil War, Americans followed the battles at home with collectable photographs of generals and prints of the battlefields that were published in the daily newspaper. But an earlier technology, stereophotography—a form of 19th-century 3-D imaging—also allowed people to view photographs from the field using a hand-held device called stereoviewer. Now, visitors to the Smithsonian Castle Building get a sense of how Americans of that era kept track of the tragic unfolding of the war’s battles and skirmishes.

“Stereophotography was less than ten years old,” explains the show’s co-curator Michelle Delaney, “but it was instrumental in bringing the image of the war into the home.”

The show “Experience Civil War Photography: From the Home Front to the Battlefront,” a collaboration between the National Museum of American History and the Civil War Trust, as well as the History Channel, is divided into three areas: the role of the Smithsonian during the Civil War, the rise of photojournalism and new photographic techniques, including stereophotography, and the home front experience.

The materials, including photographic equipment and many images that have never before been on public view, are impressive but the highlight is undoubtedly the exhibit’s clever execution of presenting 19th-century stereophotography to a 21st century audience using original Civil War era pictures.

A rotating slideshow on a large screen dramatically transforms prints into multidimensional images. Comprised of thin, even black lines, the first image of a row of soldiers lost in battle makes the bodies appear neat and compact, receding into the open field’s horizon. But using a pair of 3-D glasses, the same scene appears not as a print but as a 3-D photograph. What was at first a familiar historical image of those soldiers is now transformed into a scene both haunting and full of humanity, formed from the varying grays of shadows and light.

Though museum visitors are viewing these depictions through the red and blue cellophane glasses used for IMAX movies, they are actually seeing a photograph from the Civil War era as contemporary citizens would have before putting them into the stereoviewer.

“Three-D, which is so popular right now,” explains the exhibition’s co-curator Michelle Delaney, “actually started back in the 1850s, just before the war.”

The popularity of stereoview images was not just due to the novelty of the technology, says Delaney, but also the intimate and tactile quality of the viewing experience. “You could be in your own parlor, in your own living room, with your own stereoviewer looking at sets.” Americans could see soldiers lounging at a campsite or the dead strewn across a battlefield.”

Along with the carte-de-visite images of army generals, and reports and illustrations from correspondents, the stereoscope images were part of a media-rich landscape, says Delaney, that brought a national crisis into the domestic sphere. The war became, in part, because of proliferation of new visual material, a personal drama to the entire young country.

The Smithsonian building, which was completed in 1855, also played its own role during the war. Delaney’s was attracted to the diaries and letters from the staff and family of then Smithsonian Secretary Joseph Henry, which describe the atmosphere of anticipation that gripped D.C. as they watched battles unfold in the distance. “Secretary Henry received 12 muskets and 240 rounds of ammunition to secure the Castle,” says Delaney, but, she adds that the Institution “remained in operation, regular everyday museum operation, the entire time.” Though the Castle avoided harm, Henry was involved in military matters, advising Lincoln on scientific technologies, including the telegram and the balloon core.

“Experience Civil War Photography: From the Home Front to the Battlefront” runs from July 2012 to July 2013.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Leah-Binkovitz-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Leah-Binkovitz-240.jpg)